Introduction

Australian society today can be considered to be an example of multicultural society. Within this country multiculturalism can be defined in number of ways as an ideology that considers demographic relationships or based on policy (Leuner, 2007). If the ideological perspective is used, the definition of multiculturalism refers to the cultural and ethnic diversity that constitutes society.

However, based on public policy multiculturalism can be defined as the official recognition by governments of many different ethnic origins of their present populations, with the intention to protect and assist those who are not members of the founding majority or charter groups (Leuner, 2007).

The introduction of multiculturalism in Australian policy came about mainly due to the changing international position of the country’s economy in relation to Asia (Leuner, 2007). This prompted the Australian government to become conscious of the prevailing migration patterns around the world.

This became important given that previous policies of assimilation and integration had been found unrealistic and unachievable (Leuner, 2007). It had also been observed that what was most important for successful immigration was the preservation of cultural identity regardless of how different this was from the Australian mainstream.

In Australia there have been three distinct phases of multiculturalism namely between late 1972 to 1975, 1975 to 1983 and 1983 to 1991. During the first phase a policy known as the Structured Selection Assessment System was introduced (Leuner, 2007).

The introduction of this policy allowed a large number of non white migrants entry into Australia (Leuner, 2007). The fact that most of these immigrants were working class and likely to vote played a major role in their importance to government.

During the second phase, the government expressed interest in welfare of migrants, permitted large scale migration from Asia and increased migration targets (Leuner, 2007). The government introduced a modified version of the Canadian points system to assist in selection of immigrants. In the third phase the government increased efforts to ensure access and equity for immigrants.

These programs placed special emphasis on learning the English language and provided translators and interpreters, printing political material and advertisement of community welfare programs in community languages.

Australian Detention Centers

Despite the numerous advances over time in relation to immigrants the Australian authorities have recently come under fire due to policies and practice in relation to immigration detention (Neumann & Tavan, 2009). It is reported the between 2000 and 2005, there was significant public concern within the country due to the role of detention centers in the country.

It is reported that during this period the number of detainees, the length of detention and the conditions under which detainees were being held were at their worst (Neumann & Tavan, 2009). Many of the contributors to this discussion in the public drew their positions from the similarity between Australian detention centers and German concentration camps (Neumann & Tavan, 2009).

Such comparisons allowed the contributors to make indicate their opposition to government policy by tapping into a body of shared knowledge on the issue. The focus on this comparison however prevented the recognition of many of the institutional predecessors to detention centers (Neumann & Tavan, 2009).

This discussion will attempt to provide a historical perspective to detention centers will allow for better understanding of the policy in relation to detention and the implications on Australia as a multicultural society.

It has been reported that in the period between 1989 and 1995 almost 2000 Cambodian and Chinese asylum seekers arrived in Australia. These asylum seekers who had escaped their homelands due to political strife would make the trip to Australia by boat (Neumann & Tavan, 2009).

The arrival of Cambodian immigrants was particularly embarrassing given that Australia had played a leading role in the negotiating a UN peace agreement which it had reported to be successful.

In 1989 the government converted one disused men’s quarters of a mining company into a center to prevent asylum seekers from absconding (Neumann & Tavan, 2009). This move was also meant to keep the immigrants from press and lawyers.

Following these events and based on evaluation of the situation, in 1992 the Australian government introduced a policy of mandatory detention into the Migration Act 1958 (Neumann & Tavan, 2009). These centers are currently used to cater for two groups of non citizens.

The first group is those who arrive in Australia without a valid entry visa while the second category includes people who may have initially entered Australia with a valid visa but have overstayed, are working without valid papers or are to be removed on character grounds (Neumann & Tavan, 2009).

Based on these requirements it is possible to include persons incarcerated for over one year who will as a result breach their visa conditions. These categories of people can due to the policy be detained until they can be safely deported to their countries of origin.

The subject of immigrant detention has led to public criticism that is focused on three main aspects f this practice namely; the potential for incarceration without limit, the detention of children and the harmful effects of detention (Neumann & Tavan, 2009). This comes in light of the fact that the 1994 amendments to the Migration Act removed the time limit of 273 days (nine months).

This implies that there is currently no impediment for indefinite detention. This position is supported by the findings of the high court in 2004 that indicate an individual could be detained indefinitely if they could not be removed from the country or granted an entry visa (Neumann & Tavan, 2009).

This comes in light of the fact that the Commonwealth ombudsman has the right to review all cases of individuals detained more than two years but has no authority to order their release.

Based on the dilemma of time limit on detention the longest a person has been detained in these centers is 7 years. Based on data contained in a report on human rights it was noted that the average length of detention for a child was one year, eight months and eleven days (Neumann & Tavan, 2009). The longest serving child detainee was released in 2005 after having been detained for five years, five months and twenty days.

Though there is insufficient information to discuss the conditions within these camps, it has been concluded that the prolonged detention in the facilities has the potential to cause psychological and physical harm to detainees (Neumann & Tavan, 2009).

These medical problems relating to prolonged confinement are caused by confinement within razor wire and electric fences, remote location of some detention centers, night roll calls, inadequate sanitation in the facility and lack of mental and physical health care (Neumann & Tavan, 2009). These factors have been found to contribute to the poor health of detainees.

In addition to the above factors it has been reported that there have been examples of inhumane treatment of detainees by the staff (Neumann & Tavan, 2009). This is further complicated by the lack of mechanisms to protect detainees from abuse by staff or even fellow detainees.

The staff in the facilities is allowed to impose punishments such as solitary confinement and removal of basic rights on the detained (Neumann & Tavan, 2009). It was also reported that until 2005 there was no distinction in the treatment of children and adults.

Based on evidence following analysis one Psychiatrist noted that there was such significant similarity in the symptoms of mental illness. Based on this analysis it was possible to suggest that the cause of this mental illness was most likely the environment (Neumann & Tavan, 2009).

In the late 1990’s the issue of the detention centers was brought into the public following riots, protests and acts of self harm within the detention centers (Neumann & Tavan, 2009). The public concern on the matter was further heightened in the early 2000’s due the increased number of asylum seekers from the Middle East.

This caused the numbers in the detention centers to rise above capacity thus causing crowding and further compromising the condition within the centers (Neumann & Tavan, 2009).

The above condition did not help matters as public and the media began to increasingly focus on the issue of the detention centers. It is reported that between 2000 and 2007 there were over 150 articles and letters published that compared the facilities t German concentration camps (Neumann & Tavan, 2009).

In some of these articles the authors would draw the connection by drawing parallels or by simply referring to the centers as concentration camps. This position may have been driven further given Australia’s history in relation to administrative detention. It has been reported that Australia has long history of using administrative detention almost throughout the span of the European settlement (Neumann & Tavan, 2009).

Analysis

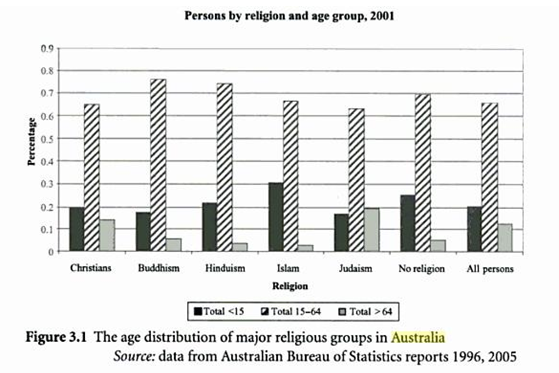

Despite the amount of damning information available on the Australian immigrant detention centers, a glimpse at statistics from Australia is likely to help shed light on the reality. It has been noted that on comparing the various religions available in the Australian population it appears the country is quite culturally diverse (Bouma, 2006).

Based on the data it is apparent that there are more Buddhists, Hindus and Muslims in Australia than Christians (Bouma, 2006). It is a known fact that these three religions are not common among the native English speakers that initially formed the nation (See Appendix A).

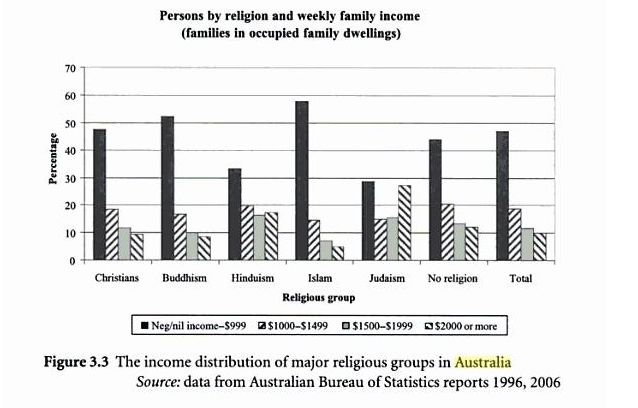

The above trend in relation to diversity is not just restricted to religion but is also evident upon observation of education statistics in the country. This was revealed on analyzing data of post high school education within the nation. In relation to completion of bachelor degree studies in the country the leading segments of the population can be classified based on various religious affiliations.

Based on this classification the largest number completing bachelor degrees was among the group affiliated to Judaism, Hinduism, Buddhism and then Islam (Bouma, 2006). Based on this classification the Christian population came fifth in the nation suggesting the existence of cultural diversity within educational institutions (See Appendix B).

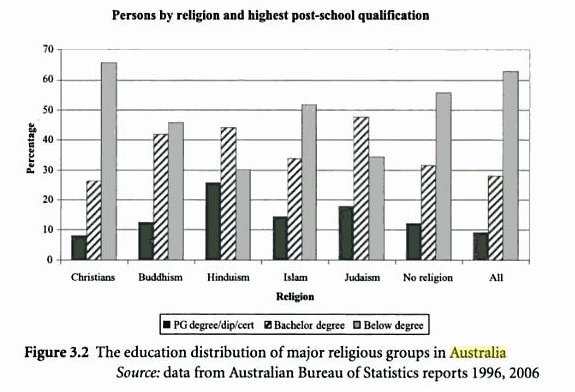

Another important observation that can be used to shed light on the position in relation to multiculturalism is the relationship between various religious groups and income. This is important as it will provide insight into how these various religious groups sit in economically within the nation (Bouma, 2006).

In observation of data that analyzes this issue it was observed that the Muslims and Buddhists lead in the weekly family income in the nation (Bouma, 2006). This suggests that there is significant evidence in support of the fact that Australia is a multicultural society (See Appendix C).

It is important t keep in mind that the policy changes that now require immigrants to be selected based on skill has gone a long way in ensuring the country attracts a number of skilled laborers (Levey, 2008). It was reported that in 2002, Australia welcomed the six millionth post war emigrant.

This lady a computer specialist from Philippines, her husband and children were among 42,000 skilled immigrants who accounted for 42% of the national intake that year (Levey, 2008). It is believed the introduction of such individuals into the country brings in productive skills and cultural richness.

Conclusion

It has been observed that changes in Australian policy on immigration came about due to the changes in the country’s relationship with Asia (Leuner, 2007). Based on this position, the government altered policies to allow immigrants to maintain cultural identity with a view to promoting successful immigration.

However, due to challenges attributed to international terrorism the government was forced to introduce policies to deter illegal immigration to the country (Arber, 2008). This came as a result of the observation that terrorism can pose serious challenges to domestic harmony (Arber, 2008).

This above position is echoed in the changes around the world that have been witnessed post 9/11 (Webb & Willis-Herrera, 2012). For this reason the policy changes in Australia appear to have been made to promote safety of the citizens as opposed to the notion that they were made to demean multiculturalism within the country.

It should be noted that in line with the issue of terrorism a number of countries in Asia are predominantly Islamic and thus the increased vigilance in relation to immigrants is not without reason (Gilly, Gilinskiy & Sergevnin, 2009). It is however important to note that it is equally important to make changes in the detention centers and procedures to avoid further social discordance.

References

Arber, R. (2008). Race, Ethnicity and Education in Globalized Times. Printed in the USA: Springer.

Bouma, G. (2006). Australian Soul: Religion and Spirituality in the Twenty First Century. Melbourne: Cambridge University Press.

Gilly, T., Gilinskiy, Y., & Sergevnin, V. (2009). The Ethics of Terrorism: Innovative Approaches from an International perspective. Springfield: Charles C. Thomas Publisher Ltd.

Leuner, B. (2007). Migration, Multiculturalism and Language Maintenance in Australia: Polish Migration to Melbourne in the 1980’s. Bern, Switzerland: International Academic Publishers.

Levey, G. (2008). Political Theory and Australian Multiculturalism. Printed in the USA: Berghahn Books.

Neumann, K., & Tavan, G. (2009). Does History Matter? Making and Debating Citizenship, Immigration and Refugee Policy in Australia and New Zealand. Canberra, Australia: ANU E Press.

Webb, D., & Willis-Herrera, E. (2012). Subjective Well-Being and Security. Printed in the USA: Springer.

Appendix

Appendix A: Religious Diversity in Australia

(Bouma, 2006).

Appendix C: Comparison of income based on religion

(Bouma, 2006).

Appendix B: Cultural Diversity in Education

(Bouma, 2006).