Introduction

Understanding parents’ perception of their children’s condition is crucial to the successful administration of the required treatment and the overall efficacy of the interventions provided to meet the needs of the target population (Bender et al. 2017). Therefore, a detailed analysis of how BAME parents perceive the risks associated with their children developing anxiety and the related disorders is essential (Delfos 2016). As a result, the foundation for a better communication process and a deeper understanding of the target patients’ needs can become a possibility (Gotham et al. 2015).

The current study aims at identifying the tendencies that BAME parents display when addressing the needs of their children with depression and anxiety. Upon the identification of the essential trends, their analysis will be carried out to determine the effects that the perceived attitudes of BAME parents have on their children (Salloum et al. 2016). As a result, the foundation for developing a set of recommendations for BAME parents as far as communication with their children with depression and anxiety issues is concerned (Patil et al. 2016).

Background

Addressing the needs of children with depression and anxiety is a challenging task because of the numerous factors that contribute to the development of the said disorders, including the problems in relationships with family members, peers, etc. The statistics of anxiety and depression in children in the U.S. is beyond upsetting; according to the official data provided by the Anxiety and Depression Association of America (2017), more than 80% of children with anxiety and around 60% of children with depression and the related disorders do not receive the required treatment. The identified issue must be viewed as a reason for serious concern since the aid disorders are likely to trigger severe consequences for children and affect their future development (Mammarella et al. 2014).

Recent studies on the subject matter highlight the gravity of understanding of how parents perceive their children’s conditions (Swenson et al. 2016). Particularly, by shifting the focus to the analysis of the parents’ perspectives on their children’s condition, one will be able to isolate the factors that may impede the process of meeting the target population’s needs and develop an appropriate management framework (Zablotsky et al. 2015; Sburlati et al. 2014). For instance, the lack of awareness about the specific needs of children with anxiety disorders may lead to the further aggravation of the condition and the comorbid issues, such as PTSD and depression (Spinhoven et al. 2014; Smith et al. 2014). Therefore, providing parents of children with the said disorders with the information about the proper behavior strategies and the approaches for meeting the children’s needs is crucial to the overall well-being of the patients (Chorpita 2016; Stallard 2014).

The specifics of parents’ perception of their children’s health issues define the success of the intervention used by healthcare experts to a considerable degree (Ozsivadjian et al. 2013; Wilmshurst 2014). Particularly, the issues associated with educating children about their disorder and how to manage it efficiently deserves to be mentioned. Children must be provided with a chance to learn more about their problems and develop the skills for addressing it independently with the support of their parents (Barber et al. 2014). Furthermore, there is ample evidence about the significance of self-help strategies: “It has been proposed that self-help strategies may relieve some of the burden on health care services” (Pennant et al. 2015, p. 3).

In other words, the active promotion of self-management and independence in managing the issues associated with depression and anxiety in children is viewed as an essential part of meeting the target population’s needs (Visser et al. 2016). Therefore, the target population must be aware of the issue and, thus, develop the skills and habits that could help adders it accordingly (Reilly et al. 2014). It would be wrong to expect children to acquire the said knowledge independently; therefore, parents must play a vital role in the process of educating children about the nature of their disorder, the ways of coping with it, and the opportunities for efficient communication that they can enjoy despite their health issue (Mian 2014). For this purpose, however, the parents should be aware of the essential techniques for addressing the needs of children with a propensity toward depression and anxiety development (Shanahan et al. 2016).

Cultural differences, in turn, affect how parents view their children’s conditions. For instance, a recent study indicates that African American fathers tend to be positive about the changes in their children’s emotional state, as well as the changes in mental health (Rahman et al. 2013). Particularly, to the PTSD developed as a loss of a sibling, Black fathers were rather optimistic about the changes in the children’s emotional dynamics:

Black fathers were more likely to rate the child’s health better “now vs before” the death; there were no significant differences by child gender and cause of death in a child’s health “now vs before” the death. (Roche, Brooten, & Youngblut, 2016, p. 190)

The identified phenomenon can be attributed to the sense of unity and the emotional connection among the family members that the African American culture implies (Reyes 2015). Thus, it is reasonable to believe that the same tendencies can be observed among African American parents with children with anxiety and depression. However, a further, more detailed analysis of the tendencies among African American parents should be carried out to determine their perception of their children with anxiety and depression (Wang & Sheikh-Khalil 2014).

A recent analysis of the parents’ perception of their children’s psychological issues also depends heavily on the emotional state of the adults (Orlans & Levy 2014). Particularly, the parents that have been experiencing depression and anxiety are more likely to show concern for their children possibly developing the same issue rather than the parents that have not experienced the problem and, therefore, are unaware of its drastic consequences (English & Lambert 2014).

Furthermore, there is a propensity among parents, in general, to prefer an adult-focused intervention as the means of addressing the problems associated with the treatment of anxiety and depression as opposed to the child-centered one: “Parents were not well aware of the possibilities regarding professional help for offspring and preferred parent-focused rather than offspring-focused interventions such as parent psycho-education” (Festen et al. 2014, p. 17). Therefore, there may be a necessity to develop a comprehensive program that could help adders to the lack of awareness among BAME parents of children with anxiety and depression regarding the management of the patients’ needs (Perou 2013).

Several studies point to the fact that anxiety and depression in children must be addressed at the earliest stages of its development and prevented, whenever possible (Urao et al. 2013; Bress 2015; Stallard et al. 2015). However, the recognition of the associated symptoms at the earliest stages of the disorder development, as well as the identification of the factors the exposure to which may trigger depression and anxiety require specific knowledge and skills, which parents need to train so that the needs of the target population could be addressed accordingly (Yap et al. 2014). BAME parents, in their turn, tend to overlook some of the opportunities that modern healthcare has to offer, according to a recent study (Forster et al. 2016).

Aims and Objectives

The study aims to determine the tendencies among BAME parents as far as the identification of possible symptoms of depression and anxiety in their children is concerned. In the course of the study, the following objectives will be achieved:

- Determining BAME’s parents a general understanding of the concepts of depression and anxiety, as well as the symptoms with which the said disorders are typically associated;

- Assessing BAME parents’ ability to identify the needs of their children correctly;

- Evaluating the adequacy of BAME parents’ response to their children’s needs as far as the issues related to depression and anxiety are concerned;

- Identifying the dents in BAME parents’ knowledge of depression and anxiety, as well as the satieties for managing them in children;

- Suggesting the tools that could help improve the process of catering to the needs of BAME children experiencing anxiety or depression issues.

It is expected that, by following the said structure and taking the steps listed above, one will be able to develop the framework for improving the current perceptions of BAME parents regarding the development of anxiety and depression in their children. Particularly, the adults will be able to recognize the problem faster and determine the ways of managing it in a manner as efficient and expeditious as possible. For instance, providing exhaustive information about the significance of contacting the local healthcare facility should be stressed when communicating with BAME parents of children with depression and anxiety issues. As a result, a gradual improvement in patient outcomes is expected.

Ethical Considerations

When researching the representatives of the target population, one must keep in mind that informed consent must be obtained from all those taking part in the research. Therefore, it will be imperative to make sure that all potential participants should sign the appropriate forms. Thus, the integrity of the study will be maintained high. Seeing that the study will be carried out among young patients, informed consent will have to be signed by their parents (Ashcroft et al. 2015).

Furthermore, it will be crucial that the patient data should not be disclosed to any third party. Consequently, the names of the patients will be replaced with codes, e.g., Patient A, Patient B, etc. therefore, keeping their data secure. Similarly, password-protected databases will have to be used to store the relevant information obtained from the study participants (Sugarman & Sulmasy 2015).

By following the essential principles of research ethics, one will be able to make sure that the integrity of the study should remain high. Furthermore, the safety and security of the participants will be enhanced. Finally, by following the essential principles of research ethics, one will create the foundation for delivering credible and trustworthy results (Pope & Mays 2013).

Method

Seeing that none of the research questions requires further data quantification, it will be reasonable to choose the qualitative method as the primary study design. Thus, one will be able to explore the specifics of BAME parents’ ability to determine the symptoms associated with depression and anxiety in their children. In other words, the attitudes of BAME parents toward the problem will have to be explored, which will require a qualitative study (Holloway & Galvin 2016).

Seeing that the nature of the phenomenon will have to be explored, the use of phenomenology as the primary study design will have to be considered. The identified framework will serve as the foundation for developing a comprehensive strategy for promoting a different perception of depression and anxiety in children among the BAME parents. Therefore, phenomenology should be viewed as the study design.

The data will be collected with the help of interviews with adults. Thus, the essential strategies used by BAME parents when addressing the possible threat of their children developing depression or anxiety disorder will be identified successfully. Furthermore, the general tendency regarding the provided responses will be outlined so that the appropriate intervention and management framework could be designed. Thus, the needs of BAME children will be addressed in a manner as efficient as possible (Donaldson et al. 2014).

The semi-structured interview format will be chosen as the means of retrieving the relevant data. Thus, the opportunities for learning essential information about the factors that compel BAME parents to succumb to certain practices of managing their children’s needs regarding the prevention of depression and anxiety will be opened. The use of the semi-structured format will allow rive the conversation in the way that the interviewer will consider preferable, yet it will also create the foundation for the interviewee to provide extra details that would remain unknown if a less flexible approach was chosen (Wears et al. 2015).

Measurement

Seeing that the data retrieved in the course of the collection process is going to be qualitative, the application of a measurement tool does not seem necessary. It could be argued, though, that the degree to which parents of BAME children address the threats of depression and anxiety development in the identified population may be assessed in the course of the study. For this purpose, a measurement instrument allowing one to evaluate the correctness of the parents’ actions and decisions may be introduced. Therefore, it may be needed to design the assessment tool that will allow comparing the perception of BAME children’s parents of their children’s possible anxiety a depression development to the perceptions that can be deemed as adequate and helpful in managing the disorders in question.

The measurement process, therefore, will imply that a comparison between the required outcome and the actual one should be carried out. As soon as the data from each parent is retrieved, an ANOVA analysis will need to be conducted so that the variance between the participants’ approach to addressing their children’s needs as far as the possibility of depression and anxiety development is concerned could be determined.

Analysis

The study will require that a total of twenty (20) participants should be recruited. The identified number of cases will allow for concluding the issue of awareness among parents of BAME children that are under the threat of developing depression or anxiety.

To reduce the level of bias in the identified research, one will have to consider the use of cluster sampling. Particularly, two specimens will be selected from each of the ethnic groups represented in the study. Thus, the credibility of the research results will increase.

The inclusion criteria will require that the participants should be under the age of twelve. The propensity toward depression and anxiety should also be viewed as one of the key inclusion criteria. Furthermore, a BAME (Black/Asian/Minority/Ethnic)) background should be listed among the inclusion criteria. By focusing on the specified population, one will be able to answer the research question properly.

The use of social media will be considered as the primary tool for recruiting research participants. By using the right social media outlets, one will be capable of identifying and a significant number of people and inviting them to participate. Particularly, the forums frequented by the parents of children with the propensity to the development of anxiety and depression will have to be viewed as the primary focus of the recruitment process. Furthermore, it will be necessary to build the list of patients that may be considered the target population for the study. Afterward, the target audience must be made aware of the research, which means that the study will have to be promoted in the identified social media as the opportunity for BAME parents to learn more about their children’s needs regarding the possibility of developing depression and anxiety disorders. It is expected that the use of the strategies mentioned above will lead to a rapid increase in the number of volunteers participating in the study.

Coding will be used as the primary tool for analyzing the qualitative data retrieved in the course of the study. Particularly, a series of codes will be developed in the process so that the essential themes and ideas could be marked in the responses provided by the BAME parents of children with a propensity for depression and anxiety. As a result, the themes that appear most frequently can be scrutinized closely. The said strategy will create the foundation for identifying the problems in the approaches used by BAME parents to address the issue in question, as well as consider the extraneous factors affecting the parents’ choices.

The codes, in turn, will be analyzed based on the frequency of their appearance in the interviews. It is assumed that the analysis will help shed some light on the principles by which the BAME parents are guided when addressing the needs of their children regarding the threats of developing depression and anxiety. For instance, issues such as family support provided to the children, the stress factors to which they have been exposed, the possible presence of comorbid issues such as PTSD, etc., will be identified and considered carefully (Neu et al. 2014).

Anticipated Research Outcomes

It is expected that the study will show the lack of awareness about the needs of children regarding the identification of possible symptoms of depression and anxiety is going to be rather low among the BAME parents. There is no need to stress the fact that meeting the needs of children that are predisposed to the development of depression, anxiety, and the associated disorders requires specific knowledge and skills. Therefore, parents are likely to lack awareness about the means of managing depression and anxiety in children. Furthermore, the specifics of the cultural background may stand in the way of parents’ recognition of their children’s problems. However, it is also expected that, in some cases, the focus on family values, the importance of positive relationships between the family members, etc., may lead to the situations in which parents may decide to reconsider their attitude toward the subject matter and start acquiring the relevant knowledge and skills helping them spot the early signs of depression and anxiety and, thus, address it accordingly.

Furthermore, it is assumed that the research will point to the cultural and socioeconomic characteristics of the target population as the key reason for the identified phenomenon to exist. Particularly, the lack of awareness regarding how depression and anxiety manifest themselves in their children is expected to root in the absence of the available resources where the required information can be retrieved. Furthermore, the unavailability of high-quality healthcare services is bound to have its toll on the perceptions of BAME parents of their children’s propensity toward depression and anxiety.

Moreover, the issues associated with information management are expected to be of huge significance as the primary cause of the wrong perceptions that BAME parents may have of their children developing depression and anxiety. Indeed, resources providing detailed information and guidance for parents that have children with depression and anxiety issues must be available to the target population. BAME parents, however, may have problems getting the identified type of help because of the socioeconomic and language-related issues. Furthermore, sociocultural prejudices about the subject matter may serve as the obstacle on the way to receiving the necessary information and developing the required skills. Therefore, information management is assumed to be one of the factors that contribute to the aggravation of the problem and lead to the further development of severe issues.

Finally, it is assumed that the research results will; help build the foundation for a follow-up study that will allow designing an appropriate tool for raising awareness among parents and testing its efficacy among the BAME population with children that are prone to the development of depression and anxiety.

Based on the outcomes of the research, the strategies for addressing the identified problems will be suggested. Particularly, it is expected that the premises for a comprehensive program aimed at raising awareness among parents will be designed.

Strengths and Weaknesses

The study has its strengths and problems. First and most obvious, the study design implies that the researchers will have to rely on the personal opinions of the research participants extensively. Therefore, there is a possibility that the information provided by the people taking part in the study is going to lack objectivity. It would be wrong to assume that the parents will deliberately provide false information about how they address the threats associated with the development of depression and anxiety in their children. However, it should be noted that the information provided by the participants will incorporate numerous personal opinions and judgments. Thus, a significant amount of the data will have to be taken with a grain of salt.

However, the suggested means of analyzing the subject matter also has its benefits. For instance, the use of interviews as the primary tool for data collection serves as the foundation for identifying the recurrent patterns and retrieving the information that will, later on, be used for designing a comprehensive strategy aimed at meeting the needs of BAME children with a propensity to anxiety and depression development. Nevertheless, it can be assumed that the research will open new opportunities for managing the needs of BASE children that may develop depression or anxiety. Particularly, a strong emphasis must be placed on active promotion of independence and knowledge acquisition among parents and children so that specific issues could be recognized easily, and that the target population could receive the required healthcare services within the shortest amount of time possible.

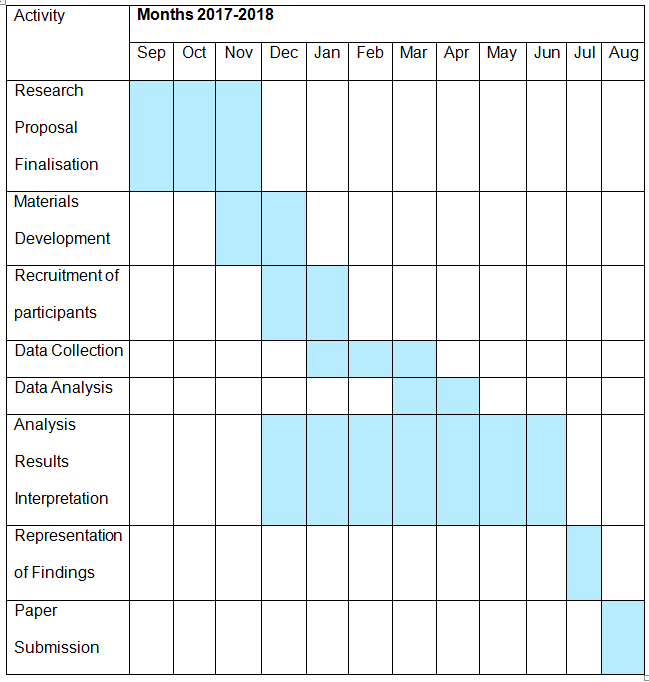

Work Plan (Gantt Chart)

The Gantt chart below shows that the research is going to be carried out in three months. Particularly, it will be necessary to receive the informed consent form the target population and design the tool for measuring the parents’ awareness of their children’s needs. Afterward, the collection of essential data will be carried out. The following analysis and the presentation of results will close the research and build the foundation for a follow-up study aimed at designing the intervention for increasing awareness rates among BAME parents and providing the required support and assistance to their children.

Reference List

Ashcroft, RE, Dawson, A & Draper, H 2015, Principles of health care ethics, John Wiley & Sons, New York, NY.

Barber, BA, Kohl, KL, Kassam-Adams, N & Gold, JI 2014, ’ Acute stress, depression, and anxiety symptoms among English and Spanish speaking children with recent trauma exposure’, Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings, vol. 21, no. 1, pp. 66-71.

Bender, SL, Carlson, JS, Egeren, LV, Brophy-Herb, H & Kirk, R 2017, ’ Parenting stress as a mediator between mental health consultation and children’s behavior’, Journal of Educational and Developmental Psychology, vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 72-85.

Bress, JN 2015, ‘Differentiating anxiety and depression in children and adolescents: evidence from event-related brain potentials’, Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, vol. 44, no. 2, pp. 238-249.

Chorpita, BR 2016, ‘Child STEPs in California: a cluster randomized effectiveness trial comparing modular treatment with community implemented treatment for youth with anxiety, depression, conduct problems, or traumatic stress’, Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, vol. 85, no. 1, pp. 13-25.

Delfos, M 2016, Are you listening to me? Communicating with children from four to twelve years old, Uitgeverij SWP BV, Amsterdam.

Donaldson, AE, Gordon, MS, Melvin, GA, Barton, DA & Fitzgerald, PB 2014, ‘Addressing the needs of adolescents with treatment resistant depressive disorders: a systematic review of rTMS’, Brain Stimulation, vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 7-12.

English, D & Lambert, SF 2014, ‘Longitudinal associations between experienced racial discrimination and depressive symptoms in African American adolescents’, Developmental Psychology, vol. 50, no. 4, pp. 1190-1196.

Festen, H, Schipper, K, Vries, SOD, Reichart, CG., Abma, TA & Nauta, MH 2014, ’Parents’ perceptions on offspring risk and prevention of anxiety and depression: a qualitative study’, BMC Psychology, vol. 2, no. 1, pp. 17-31.

Forster, AS, Rockliffe, I, Chorley, AJ, Marlow, LA, Bedford, H, Smith, SG, Waller, J 2016, ‘Ethnicity-specific factors influencing childhood immunisation decisions among Black and Asian Minority Ethnic groups in the UK: a systematic review of qualitative research’, Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, vol. 16, no. 1, pp. 1-6.

Gotham, K, Unruh, K & Lord, C 2015, ‘Depression and its measurement in verbal adolescents and adults with autism spectrum disorder’, Autism, vol. 19, no. 4, pp. 491-504.

Holloway, I & Galvin, K 2016, Qualitative research in nursing and healthcare, John Wiley & Sons, New York, NY.

Mammarella, IC, Ghisi, M, Bomba, M, Bottesi, G, Caviola, S, Broggi, F, & Nacinovich, R 2014, ‘Anxiety and depression in children with nonverbal learning disabilities, reading disabilities, or typical development’, Journal of Learning Disabilities, vol. 49, no. 2, pp. 130-139.

Mian, ND 2014, ‘Little children with big worries: addressing the needs of young, anxious children and the problem of parent engagement’, Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, vol. 17, no. 1, pp. 85-96.

Neu, M, Matthews, E, King, N, Cook, PF & Laudenslager, M 2014, ‘Anxiety, depression, stress, and cortisol levels in mothers of children undergoing maintenance therapy for childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia’, Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing, vol. 31, no. 2, pp. 104-113.

Orlans, M & Levy, TM 2014, Attachment, trauma, and healing: understanding and treating attachment disorder in children, families and adults, Jessica Kingsley Publishers, London, UK.

Ozsivadjian, A, Hibberd, C & Hollocks, NJ 2013, ‘Brief report: the use of self-report measures in young people with autism spectrum disorder to access symptoms of anxiety, depression and negative thoughts’, Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, vol. 44, no. 4, pp. 969-974.

Patil, RN, Nagaonkar, SN, Shah, NB, Bhat, TS, Almale, B, Gosavi, S & Gujrathi, A 2016, ‘Study of perception and help seeking behaviour among parents for their children with psychiatric disorder: a community based cross-sectional study’, The Journal of Medical Research, vol. 2, no. 1, pp. 6-11

Spinhoven, P, Penninx, BW, Hemert, MAV, Rooij, MD & Elzinga, BM 2014, ‘Comorbidity of PTSD in anxiety and depressive disorders: prevalence and shared risk factors’, Child Abuse & Neglect, vol. 38, no. 11, pp. 1320-1330.

Pennant, ME, Loucas, CE, Whittington, C, Creswell. C, Fonagy, P, Fuggle, P, Kelvin, R, Naqvi, S, Stockton, S & Kendall, T 2015, ‘Computerised therapies for anxiety and depression in children and young people: a systematic review and meta-analysis’, Behaviour Research and Therapy, vol. 67, no. 1, pp. 1-18.

Perou, D 2013, ‘Mental Health Surveillance Among Children – United States, 2005-2011’, Supplements, vol. 62, no. 2, pp. 1-35.

Pope, C & Mays, N 2013, Qualitative research in health care, John Wiley & Sons, New York, NY.

Rahman, A , Surkan, PJ, Cayetano, SE, Rwagatare, P & Dickson, KE 2013, ‘Grand challenges: integrating maternal mental health into maternal and child health programmes’, PLOS Medicine, vol. 10, no. 5, p. e1001442.

Reilly, C, Atkinson, P, Das, KB, Chin, RFMC, Aylett, SE, Burch, V, Gillberg, C, Scott, RC & Neville, BGR 2014, ‘Neurobehavioral comorbidities in children with active epilepsy: a population-based study’, Pediatrics, vol. 133, no. 6, pp. 1-14.

Reyes, ADL, Augenstein, TM, Wang, M, Thomas, SA, Drabick, DAG, Burgers, DE & Rabinowitz, J 2015, ‘The validity of the multi-informant approach to assessing child and adolescent mental health’, Psychological Bulletin, vol. 14, no. 4, pp. 858-900.

Roche, RM, Brooten, D & Youngblut, JM 2016, ‘Parent & child perceptions of child health after sibling death’, International Journal of Nursing & Clinical Practices, vol. 3, no. 1, pp. 185-199.

Salloum, A, Swaidan, VR, Torres, AC, Murphy, TK & Storch, EA 2016, ‘Parents’ perception of stepped care and standard care trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy for young children’, Journal of Child and Family Studies, vol. 25, no. 1, pp. 262-274.

Sburlati, E. S., Lyneham, HK, Schniering, CA & Rapee, RM 2014, Evidence-based CBT for anxiety and depression in children and adolescents: a competencies based approach, John Wiley & Sons, New York, NY.

Shanahan, L, Zucker, N, Copeland, WE, Bondy, C, Egger, HL & Costello, EJ 2016, ‘Childhood somatic complaints predict generalized anxiety and depressive disorders during adulthood in a community sample’, Psychological Medicine, vol. 45, no. 8, pp. 1721-1730.

Smith, P, Perrin, S, Yule, W & Clark, DM 2014, Post traumatic stress disorder: cognitive therapy with children and young people, Routledge, New York, NY.

Stallard, P 2014, Anxiety: cognitive behaviour therapy with children and young people, Routledge, New York, NY.

Stallard, P, Skryabina, E, Taylor, G, Phillips, R, Daniels, H, Anderson, R & Simpson, N 2015, ‘Can school-based CBT programmes reduce anxiety in children? Results from the preventing anxiety in children through education in schools (PACES) randomised controlled trial’, European Psychiatry, vol. 30, suppl. 1, 28-31.

Sugarman, J & Sulmasy, DP 2015, Methods in medical ethics, Georgetown University Press, Washington, DC.

Swenson, S, Ho, GWK, Budhathoki, C, Belcher, HME, Tucker, S, Miller, K & Gross, D 2016, ‘Parents’ use of praise and criticism in a sample of young children seeking mental health services’, Journal of Pediatric Health Care, vol. 30, no. , pp. 49-56.

Urao, Y, Yoshinaga, N, Asano, K, Ishikawa, R, Tano, A, Sato, Y & Shimizu. E 2013, ‘Effectiveness of a cognitive behavioural therapy-based anxiety prevention programme for children: a preliminary quasi-experimental study in Japan’, Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 4-15.

Visser, SN, Bitsko, RH, Danielson, M, Gandhour, R, Blumberg, SJ, Schieve, L, Holbrook, J, Wolraich, M & Cuffe, S 2016, ‘Treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder among children with special health care needs’, Journal of Pediatrics, vol. 166, no. 6, pp. 1432-1430.

Wang, MT & Sheikh-Khalil, S 2014, ‘Does parental involvement matter for student achievement and mental health in high school?’, Child Development, vol. 85, no, 2, pp. 610-625.

Wears, RL, Hollnagel, E & Braithwaite, J 2015, Resilient Health care, volume 2: the resilience of everyday clinical work, Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., Farnham, UK.

Wilmshurst, L 2014, Essentials of child and adolescent psychopathology, John Wiley & Sons, New York, NY.

Yap, MBH, Pilkington, PD, Ryan, SM & Jorm, AF 2014, ‘Parental factors associated with depression and anxiety in young people: a systematic review and meta-analysis’, Journal of Affective Disorders, vol. 156, no. 1, pp. 8-23.

Zablotsky, B, Pringle, BA, Colpe, LJ, Kogan, MD, Rice, C & Blumberg, SJ 2015, ‘Service and treatment use among children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorders’, Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics, vol. 36, no. 2, pp. 98-105.