Introduction

‘Zines first emerged as a genre in the early 1930s in the United States and peaked during the Cultural Revolution of the 1970s. The first ‘zines were called fanzines since they were about science fiction. ‘Zines were handcrafted by fans using print media such as mimeographs in the 1930s and xerography in the 1970s. These were completely independent publications not limited by editorial policy or censorship, including political censorship.

Punk ‘zines passed from hand to hand and served as a mouthpiece for the younger generation in countries like the United Kingdom, the United States, Germany, and Spain. Punk ‘zines mainly covered the themes of youth music culture and were an expression of their creators’ individual visual creativity. This paper aims to discuss how, why, and in what ways British punk ‘zines were a fundamental resistant element of the sociopolitical climate of the 1970s.

Punk ‘Zines in UK, Spain, and Germany

The first punk ‘zine emerged in December 1975 in New York. It was published by John Holmstrom and was called “Punk Magazine,” which gave the name to the whole ‘punk’ community. After that, the first punk ‘zines appeared in the UK; these were issues such as Sniffin ‘Glue, Ripped & Torn, Chainsaw, and Panache. In the UK, Spain, and Germany, the punk ‘zines were in many ways the means of resistance to political and social turbulence. Scholars note that punk ‘zines and rave subculture greatly impacted the youth’s sensitivity to everyday issues. The youth resistance first developed the global character at that time.

It is worth considering what punk ‘zines mean in Spain and Germany’s sociopolitical context to present a wider picture of punk zines’ cultural and sociopolitical influence in Europe. In Spain, in 1982-1989, the punk culture was present in the form of the Basque Radical Rock movement. This movement was inspired by British punk culture and appeared as the reaction to the new freedom brought by the fall of General Franco’s regime in 1975. As an authoritarian ruler, Franco was solving only some problems of the society. Simultaneously, issues related to modernization, such as urbanization, industrialization, the crisis in traditional sectors, and new inequalities, remained unsolved and caused dissatisfaction and frustration. This frustration had to be overcome, and it did, through the new wave of Spanish punk rock culture. Therefore, in Spain, punk rock was closely bound with the resistance movement and was associated with the new era of modernization and political freedom.

In Germany, the sociopolitical and cultural situation was even more specific and more diverse than in Spain. At the end of the 1970s, when the punk ‘zines emerged, Germany existed in the form of two separated states divided by the Berlin Wall – the German Democratic Republic (GDR), ruled by Soviets, and the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG) that was leaning towards the modern European cultural and political currents. Interestingly, punk ‘zines culture here flourished in both states and eventually contributed to the recreation of the united German nation after the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1988. The subculture of punk ‘zines, inspired by the success in Britain, appeared as early as 1977 in Western German, the FRG. The first punk rock and punk ‘zine groups and venues emerged in Düsseldorf, West-Berlin, Hamburg, and Hanover and spread throughout the state by the end of 1977. In Düsseldorf and Hanover, the punk ‘zine culture gave an impetus to the growing popularity of punk rock culture and contributed to the development and touring of young punk bands within local scenes. On the contrary, in West Berlin and Hamburg, the movement was considered rather political.

The UK was the historical homeland for punk ‘zines, which emerged in London. The first UK punk ‘zine was called Sniffin’ Glue and existed from 1976 to 1977. It was published by Mark Perry, a young bank clerk, who created the ‘zine at his London apartment using a personal typing machine. With the first 60 copies of the first edition, it was a colossal success. The latter editions reached the numbers of over 12,000 copies distributed from hand to hand and produced using xerography. The UK zines created using the famous DIY technique encouraged the readers to flood the market with pink writing. There was a massive acceleration of ‘zines in the UK, Germany, and other countries in the following years.

Techniques Used to Produce ‘Zines

Producers of punk ‘zines used the DIY technique, which meant they utilized whatever was available at hand for magazine production and publication. Scholars admit that “it remains within the subculture of punk music where the homemade, A4, stapled and photocopied fanzines of the late 1970s fostered the do-it-yourself (DIY) production techniques of cut-n-paste letterforms, photocopied and collaged images, hand-scrawled and typewritten texts, to create a recognizable graphic design aesthetic”. Interestingly, the DIY technique that created fanzines was very well suited to punk ‘zines. It allowed creating a unique, idiosyncratic visual image through which authors conveyed cultural and sociopolitical resistance ideas.

Noteworthy, the London of the 1970s was a somewhat dysfunctional space due to the economic depression of the late 1970s and the state policy of Margaret Thatcher. The latter insisted on the abolition of social benefits and guarantees for the population. The period of the economic crisis meant that most people lost their jobs in the manufacturing sector and were struggling with the challenges of survival. The general tense atmosphere affected the youth, who found a way to confront poverty and insecurity, offering to create a culture independently. It was the value of the DIY approach, as it allowed not relying on the official media and third-party funding, which was greatly reduced in all areas of life areas.

‘Zines weren’t just magazines that let the audience have fun while reading exciting news from the world of music. Their main advantage was a vast distribution network through which tens of thousands of magazines were delivered every month. Thanks to this network’s existence, young musical groups could develop, arranging tours within the country and traveling to neighboring countries. DIY culture suggested that the music will be created by the musicians’ efforts, using available means to record and distribute albums and not relying on the established music labels.

One famous punk ‘zine included a post that drew three basic guitar chords and explained how to play them. The illustration was accompanied by a note: “Here are three guitar chords – now create a band.” The same approach was implied with the creation of ‘zines when publishers called to flood the market with them. Probably, being able to entirely rely on one’s strength in creating and distributing a cultural product made the participants feel very confident and made it possible to challenge social and political norms and standards.

‘Zines were much like school newspapers or fan diaries, and the first ‘zines were entirely handwritten. However, later on, printing media began to be used more and more widely to create zines. Experts say that publishers often used the copying equipment available at their place of work or study. Mark Perry created his Sniffin’ Glue using a typewriter and handwritten edits to create a lively editorial feel. Mark Perry was the first to come up with the idea to create punk ‘zines, and the first issues were produced exclusively by him. Punk ‘zines featured newspaper clippings and photographs of famous bands like the Sex Pistols and Led Zeppelin. ‘Zines also posted photos of unknown bands, allowing everyone to become famous.

Sociopolitical and Cultural Influence

In the case of Sniffin’ Glue, produced by Mark Perry, he used reports from amateur journalists he knew and included cultural, music, and political news in its newscasts. Remarkably, the punk movement consisted mainly of people who identified themselves as working class, as opposed to the hippie movement, which was composed of the middle class. By the late 1970s, it was entirely absorbed by the mainstream culture of show business.

Punk culture also eventually assimilated into mainstream culture. In the 1980s, more and more national media outlets published news and coverage of punk concerts and offered information about punk music. It is believed that Mark Perry stopped releasing Sniffin’ Glue precisely because punk culture began to receive enough coverage in the mainstream media, and most of the readers switched to them.

Nevertheless, visual images, which often used obscene language, allowed young people to creatively criticize the economic disorder and chaos prevailing in the country and create something like their own political platform. However, although some critics have compared ‘zines with pamphlets of famous revolutionaries, they had nothing to do with purely political movements. Punk ‘zines were primarily a platform for creative expression. Simultaneously, punk ‘zines had a deep ideology based on freedom, creativity, self-expression, equality, and non-discrimination. Echoes of this ideology were subsequently adopted by many political parties and incorporated into political programs.

The main ideas and themes presented in ‘zines reflected the latest social, cultural, and political trends in Great Britain. Several publications dealt with cross-cutting issues of politics, the spread of pornography, social discrimination, and suppression of the working class’s rights. ‘Zines were also the quintessential visual culture, allowing many amateur artists to create unique images and photo collages. But first and foremost, ‘zines were a way of spreading information, exchanging messages about concerts and performances, which allowed bands to tour and tour without managers’ help, relying on the ‘zines culture. It was an advertisement tool, a platform for exchanging opinions, an outlet for creativity, and a platform for news from the world of music.

Sniffin’ Glue – the First UK ‘Zine

The first punk ‘zine in the UK, Sniffin’ Glue, was created by Mark Perry, who published it for two years. The main themes presented in ‘zine were events in music and culture and the presentation of a new perspective on social and political trends. The magazine covers featured world-famous punk rock bands like Ramones, Sex Pistols, and Led Zeppelin. The magazine’s title was borrowed from Ramone’s song “Now I Wanna Sniff Some Glue.” Mark Perry, who was 19 years old when the first issue arrived, initially created the ‘zine by himself, using a typewriter donated by his parents, making handwritten edits, and pasting newspaper and magazine clippings. Later, after the release of the first issues, which were huge successes, Mark enlisted his sister and friends’ support, who offered to use xerography since their alma mater had such equipment.

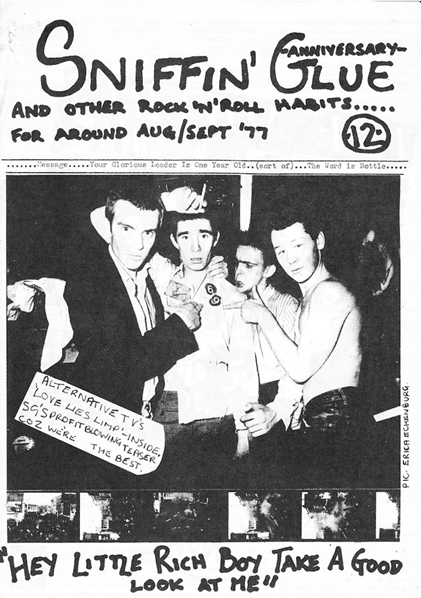

The 12th-anniversary issue of the Sniffin’ Glue of August 1977, the cover of which is shown in the picture below, is today stored in the Internet Archive in the form of electronic photocopies. This punk zine consists of 28 pages, which present announcements of new records and concerts, discuss the news about the investment in the independent reggae label Rough Trade, the history of the Chiswick group, and the phenomenon of Generation X. Text typed on a typewriter looks especially aesthetically pleasing. The use of xerography smooths out the jaggedness of photo collages and creates a unique visual texture of the ‘zine. Mark Perry published 12 issues in total, starting in July 1976 and ending in August 1977.

Opinions on ‘Zines

Although the ‘zines have ascribed historical meaning, they aimed to promote self-expression and exposure to unique moments in the present. In addition to being aligned with political currents, ‘zines also expressed freedom from the mainstream in the broadest sense. Because ‘zines started as science fiction fanzines in the United States of the 1930s, they carried the idea of independent fan creativity, which helped spread the concept of self-creation of ‘zines. Punk ‘zines have shaped generations of Europeans and Americans, creating a unique platform for cultural discourse.

According to scientists, people perceived ‘zines as a source of initial attraction and exposure to punk culture. Many college students and graduates who were exposed to this culture have made it a part of their lives forever. Readers were also sensitive to the Do-It-Yourself culture’s values, which changed the traditional view of what real creativity should be. In the US, DIY culture gave an impetus for the emergence of many musical record brands such as SST, TwinTone, Epitaph, BYO, and ROIR. Bands like Black Flag, Youth Brigade, Minor Threat, and the Dead Kennedys rose from the punk movement and DIY culture. Most of the study participants also believed that the First Wave of punk culture had a bright political aspect in England due to the depression and economic crisis.

Conclusion

Thus, it was discussed how, why, and in what ways British punk ‘zines were a fundamental resistant element of the sociopolitical climate of the 1970s. The US punk movement inspired British punk ‘zines, which inspired Spain and Germany’s punk movements. The unique political and economic events of the late 1970s were reflected in the pages of punk ‘zines. However, the political component has not turned the ‘zines into traditional media, nor has it changed their unique approach to presenting the information. Punk ‘zines utilized the ideology of freedom and creative expression, which was subsequently adopted by many political platforms and organizations. For the ‘zines, however, the source and purpose of this ideology were to keep the creative process alive, to immerse and familiarize the reader with the world of musical and cultural resistance.

Bibliography

Lahusen, Christian. “The Aesthetic of Radicalism: The Relationship between Punk and the Patriotic Nationalist Movement of the Basque Country.” Popular Music 12, no. 3 (1993): 263-280.

Leishman, Kirsty. “Explainer: Zines.” The Conversation. Web.

Melin, Daniel. “The Rise and Fall of Zines.” Split Magazine. Web.

Moran, Ian. “Punk: The Do-It-Yourself Subculture.” Social Sciences Journal 10, no. 1 (2010): 58-65.

Savage, Jon. “Fanzines: The Purest Explosion of British Punk.” The Guardian. Web.

Schmidt, Christian. “Meanings of Fanzines in the Beginning of Punk in the GDR and FRG.” La Presse Musicale Alternative 5, no. 1 (2006): 47-72.

Triggs, Teal. “Scissors and Glue: Punk Fanzines and the Creation of a DIY Aesthetic.” Journal of Design History 19, no. 1 (2006): 69-83.

Tschida, Anne. “Zines, Where Words and Visuals Collide.” Knight Foundation. Web.

Wilson, Brian. “Ethnography, the Internet, and Youth Culture: Strategies for Examining Social Resistance and “Online-Offline” Relationships.” Canadian Journal of Education 29, no. 1 (2006): 307-328.

Worley, Matthew. “Punk, Politics, and British (fan)zines, 1976-84: ‘While the World Was Dying, Did You Wonder Why?’” History Workshop Journal 79, no. 1 (2015): 76-106.