Organizational overview

Hennes & Mauritz AB (H&M) was incepted way back in 1948 and has been an active player in the designing, manufacturing, distribution and selling of clothing materials. It is based in Sweden with several marketing points both at the local and international level (H & M., 2005).

For decades now, the company has been a major competitor in the clothing industry by producing a wide range of clothing designs and the associated accessories.

For instance, its clothing range include but not limited to footwear, cosmetic products and related accessories, sports fittings for all both minors and adults as well as inner-wears for all type of users (Just-style.com., 2011).

To date, there are an estimated 20 production offices hosted by the company. In terms of its supplies especially for raw materials, H&M has a wide network of independent suppliers derived from Europe and Asia who provide the company with adequate goods need for continued production.

Moreover, the company has so far managed to expand its operations in over 37 countries with an estimated two thousand retail outlets spread across these locations (H & M., 2008). Nonetheless, Sweden, United Kingdom and Germany still serve as the principle markets for H&M.

In terms of marketing, H&M makes use of a mixed variety of marketing strategies in order to reach out for its wide clientele base. For instance, it is currently embracing online marketing through the internet as well as catalogues which are found both online and in the real physical stores.

As part of its geographic expansion program, internet marketing has been adopted beyond Sweden, the host country for the company. Customers in Austria, Germany, the Netherlands, Norway, Finland and Denmark can now obtain product details through online shops and catalogues.

As already mentioned, H&M was established towards the close of 1940s. The brain child behind the company was Erling Persson. During the threshold years, the company was dealing with women’s clothing, but it later diversified to incorporate clothing needs for the entire family.

The expansion into men’s wear in 1968 was occasioned by the acquisition of Stockholm hunting equipment store which had been mainly dealing with men’s fittings. Mauritz Widforss was a key player in male clothing and upon its acquisition by Persson, H&M broadened its production perspective.

Consequently, the new acquisition together with the old store was rebranded as Hennes & Mauritz (H&M). currently, most of the manufacturing courtesy of H&M is carried out in most European and Asian countries such as Turkey, Pakistan, India, Egypt, China and Bangladesh (H & M., 2008).

Research objectives

The main objective of this research study is to explore, evaluate and critically analyse the major changes that took place in H&M from 2005 to 2010. In addition, the paper seeks to incorporate the latest models and change theories that are relevant to H&M.

Research methodology

The availability of sufficient data on the activities of H&M since it was established will, indeed facilitate the research work on this topic. Hence, secondary research will be used throughout the research study.

Consequently, information for the essay will be acquired through the internet, books, journal articles, magazines, and newspapers.

Scope and limitations of the research

This research study aims at circumnavigating through the changes which took place in H&M between 2005 to 2010 with the application change models and theories pertaining to the company.

Although secondary research method may be quite smooth to undertake since it entails referring other people’s work, this research method is not void of its own limitations.

For instance, there is a higher likelihood of encountering outdated sources or those that require permissions to access. Such limitations may hinder the validity and soundness of information being gathered (Carnall, 2003; Colville et al., 1993).

Key changes in H&M from 2005 to 2010

Geographical expansion

One of the development agenda that H&M has embarked on since 2005 is the opening up of new branches across the borders. For instance, the company has been on the forefront towards opening up new stores in other countries.

One of such latest development is its expansion to Croatia (Haas & Hayes, 2006). Way back in 2009, South Korea was also benefitted from another store courtesy of H&M. the new store was located in the South Korean capital although actual operations was started in spring of 2010.

Marketing

H&M has diversified its marketing strategies to include more than just use of catalogues and internet marketing. For example, the song “Hang to market its brand of clothing materials and related accessories (Just-style.com., 2011).

This was a sharp divergence from the previous traditional modes of marketing whereby consumers could only be reached out ordinary TV and radio ads. Its UK website used the song as the background music.

Partnerships

A collection by McCartney was launched by the company towards the end of 2005 as part of the new form of collaboration that was perceived would improve the trading activities of the company. A year later, Victor & Rolf designers from Dutch also entered into some form of partnership or collaboration.

The pop star Madonna also graced yet another collaboration in March 2007, while in mid the same year, game developers Maxis worked with H&M in developing a computer game that would not only boost the publicity and likeability of the company, but also market H&M staff rigorously.

All these new collaborations were aimed at improving the image of the company while at the same time laying a firm a foundation for the competitive and dynamic market (Hayes, 2002).

Roberto Cavalli, an Italian designer also collaborated with H&M from November 2007. This was a marketing mix that led to heavy selling by H&M. before the end of 2007, another collection of designs was launched in China with the need to popularize H&M products in the Far East.

Comme des Garcons, a Japanese company, was appointed as a designer in the guest level in the fall of 2008.

Mathew Williamson, a British designer, also partnered with H&M in the spring and summer of 2009 when he developed two outstanding design portfolios for the company. In one of the collections, women’s fittings were dispatched in some appointed stores.

In the second range of designs, H&M was supplied with men’s clothing that was only floated in selected outlets. This was notably the first time when Williamson was branching into men’s wear, through the changes brought in by H&M.

A limited edition was released by the company in November 2009 with a price range of between 30-70 pounds. This was done through diffusion collection, hosted by Choo Jimmy. Most of the clothing items introduced in this edition was comprised mainly of shoes for both men and women as well women’s handbags.

Another interesting change in this edition was that clothing designs by Choo found their entry into H&M marketing ring for the same time.

Additionally, lingerie and ladies’ knit wear were also introduced into several stores in 2009 from Sonia Rykiel designers. Lanvin, a French fashion centre, also partnered with H&M in the fall of 2010 when it was launching its 2010 designer in the guest level.

Home furnishing

In order to diversify its trading portfolio, H&M announced the intention of venturing into furniture market especially those used in households. The internet catalogue of the company played a crucial role in 2009 in advertising the various home furnishing offers.

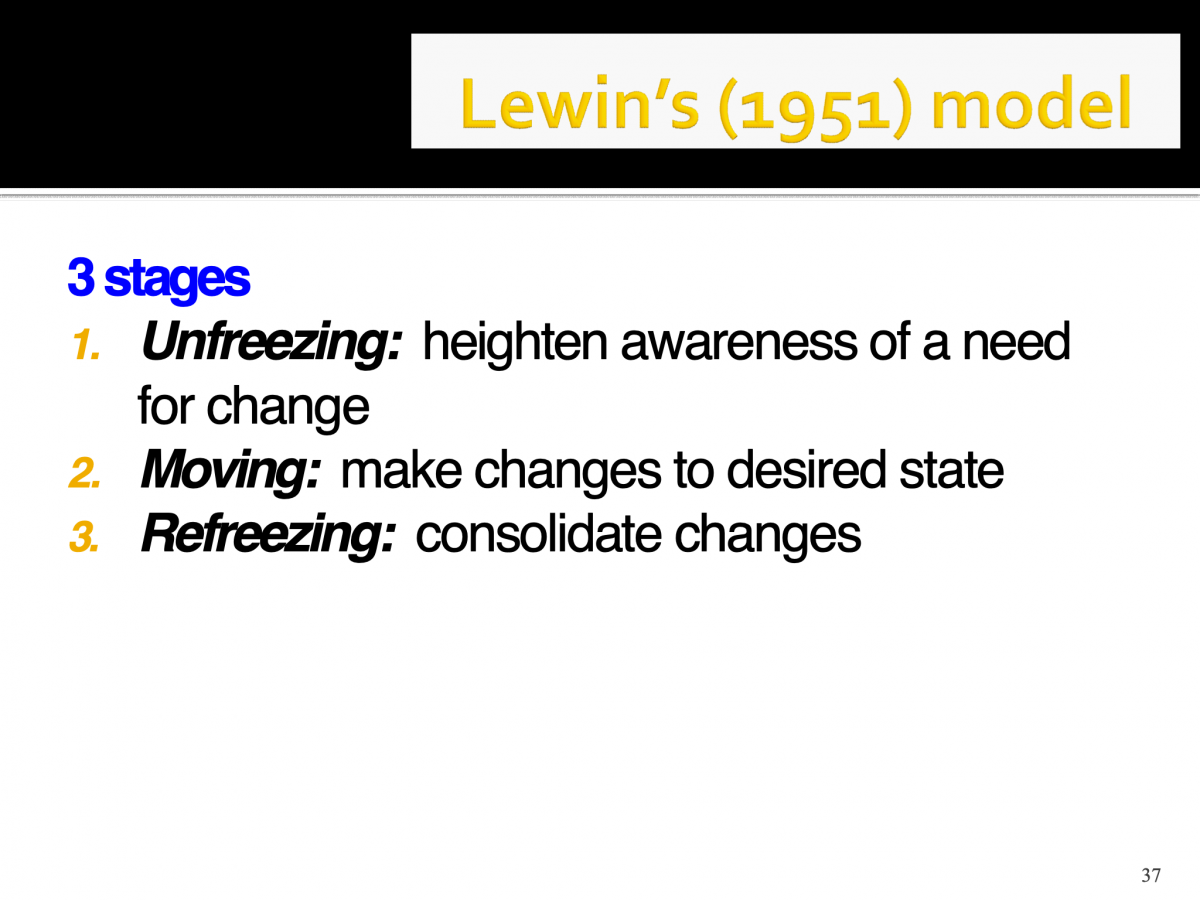

However, sales of home furniture are only implemented in locations where H&M accepts online buying. Some of these countries include United Kingdom, Sweden, Norway, the Netherlands, Germany, Finland as well as Denmark. The Lewin’s model as illustrated in the diagram below:

Indeed demonstrates that H&M has realized the importance of business diversification by accomplishing the three stages of change namely unfreezing, moving and refreezing whereby all the changes that have been implemented are consolidated so that there worth can easily be assessed or evaluated by the management of the organization.

Environment

In its production activities, H&M has been faced with myriad challenges on matters pertaining to the environment.

Government regulations across various countries where the company operates demand environmental impact assessment to be done in order to ascertain the risk level of industrial activities at any given time. It is against this backdrop that H&M began to critically assess and evaluate the carbon foot print of its production process.

In 2008, the company embarked on a rigorous product stewardship and supply chain management that would ensure safe use of the immediate environment where manufacturing takes place.

As a result, the company opted for a joint approach in not only highlighting the prevailing challenges posed to the environment but also holistic control methods that could be adopted to control any associate environmental degradation (Burnes, 2004).

Consequently, H&M together with Business for Social Responsibility (BSR) laid down a robust plan for investigating the carbon emission level to the environment with the aim of controlling the emission at the point of exit.

Both the available resources at the public domain as well as expert opinions were integrated in this Research and Development (R&D) study on environmental pollution by carbon.

Philanthropy

Although the company has been undertaking charitable projects for long, June 2008 was phenomenon since it initiated a joint effort by UNICEF in order to fight against deteriorating situation of child labour in Uzbekistan.

The Philanthropy department of the company felt that the cotton industry in this country was abusing the efforts of children who were also far much under age to work in cotton firms. This time round, H&M decide to approach the issue differently in order to improve the condition of these children.

For instance, the devastating effects of child labour were combated by raising public awareness.

Another notable change carried out during this campaign was to champion on the child protection strategies that would positively affect the condition of children nationally. Past campaigns of this nature did not employ such approaches.

In order to facilitate the project, the company contributed a sum of one hundred and fifty thousand dollars. This amount was used to finance the first phase of the project.

In 2008 alone, the company opened a total of 214 additional stores. Moreover, Weekday and Monki stores totaling to 20 were also acquired by H&M in a bid to expand its trading activities. During the same period, the company opened an outlet in Japan, again for the first time.

This new store proved to be highly profitable compared to other outlets that had been opened in the past. A higher percentage of FaBric Scandinavian shares were also acquired by H&M thereby expanding the portfolio of the latter (Tate, 2009).

Changes in corporate governance

Sweden is the country of origin for H&M and as a result, it is demanded by law for the company to adhere strictly to the corporate governance code.

In 2008, the company was compelled to make necessary adjustments in its corporate governance structure especially in Sweden. This was in line with providing relevant information upon request by the authorities (Burnes, 2000; Burnes, 2004; Luecke, 2003; Schuler & Jackson, 2007).

Annual General Meeting

The Company changed its annual general meetings rule in 2005. From the 2005 resolution, participation in the meetings were not allowed. On the other hand the distance participation rule applied to those shareholders who could not be visibly present during Annual General Meetings (Mayle, 2006; Hickson & Pugh, 2005).

Election Committee

An election committee was formed based on the resolutions of the AGM held in April 2005. Initially, it was known as the nomination committee but the company opted to broaden its roles so that it could handle all matters related to elections (Burke, 2008). The new resolutions adopted include the fact that the Election Committee members are to be appointed by the largest shareholders totaling to five and also the primary shareholder.

Theories, models and issues arising from the study

One of the most outstanding occurrences that have taken place at H&M since 2005 is organizational change with respect to the various aspects that have already been explained in the above section (Bratton & Gold, 2001; Sinclair-Hunt & Simms, 2005).

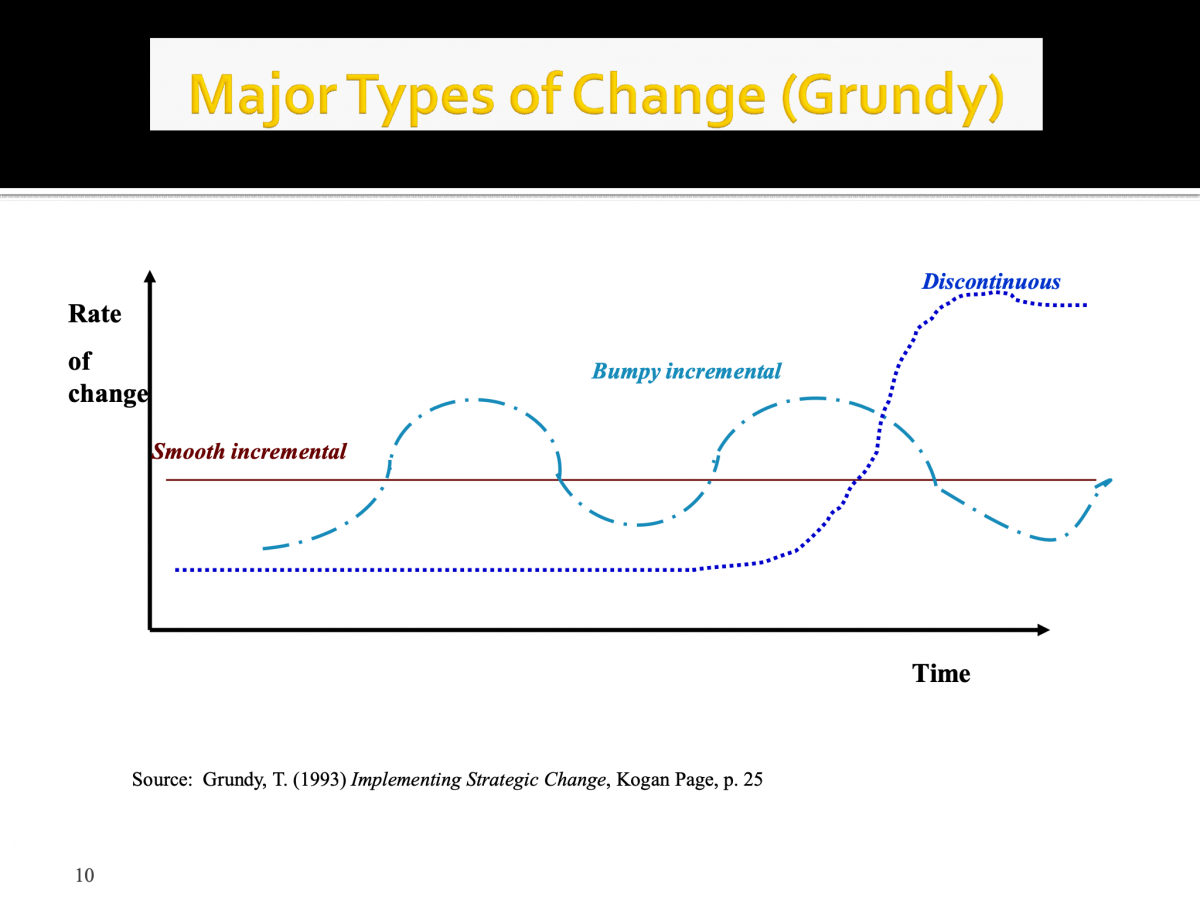

According to the Grundy model below,H&M has adopted both major and various types of changes. For instance, the rate of change in terms of geographical expansion has surpassed the normal or ‘smooth incremental level’ in the Grundy model.

It is one of the major change H&M has undertaken since 2005. The various changes at H&M have both revolved and evolved the company to emerge as one of the market leaders in the production and sale of clothing items and related accessories as shown below.

When managers are carrying out strategic planning, change manage is usually top in the priority list (Boxall et al., 2003). Proper planning cannot be eluded if change management is to be effected in the right way (Bullock & Batten, 2005; Henry et al., 2002; Kakabadse, A.; Bank & Vinnicombe, 2004).

In as much as changes are inevitable in organizations, the process of implementation should be thorough if not keen so that those who will be affected by the very changes are either involved or consulted beforehand (Leifer, 2009; Ricketts, 2002; Salaman & Asch, 2003).

This is necessary in order to minimize nay form of gross resistance to the proposed changes. In the case of H&M, the changes implemented by the company between 2005 and 2010 could only be fruitful if employees were made part and parcel of the entire process (Rieley & Clarkson, 2001).

In addition, change management by H&M can only be functional if they are proved to be quite reasonable and pragmatic (Kanter, Stein & Jick, 1992; Salaman, Storey & Billsberry, 2005; Storey, 2004).

It is also important that the suggested changes can be achieved within a given time frame as well as measurable (Bond,1999; Buchanan & Badham, 2008; Burnes,1996).

Nonetheless, it should be noted that these ideals can positively impact an organization if they are first applied at the level of an individual, then to small working teams before the overall effect can spill over to the entire organization (Kogut & Zander, 2002; Senior & Swailes, 2010).

Hence, this theory demands that H&M should value the integral role played by small groups or teams within the various departments of the organization (Hodgetts et al., 2000; Holloway, 2002; Jones, Conway & Steward, 2001; Love, Gunasekaran & Li, 2008; Lynch, 2003).

Needless to say, organizations that do not envisage the value of team building hardly penetrate through with the set goals and objectives (Nonaka & Takeuchi, 2005; Sathe, 2003).

Better still; employees should be taken as architects of change (Kang, Oah & Dickinson, 2003; Kanter, 2003; Lee, 2003). They merely act as instruments of pursuing change in organizations (McKenna, 2000; Patton & McCalman, 2008; Raney & Clark, 2010).

How H&M can manage change effectively

As already mentioned, proposed changes with an organization can only be successful when they are applied from an individual level since an organization is realistically made up of individual employees (Davidson & DeMarco, 1999; Dawson, 1994; Katz & Kahn, 2008).

To begin with, the management at H&M needs to have thoughtful planning before implementing any change (Holloway, 2002; Peper et al., 2005; Robbins, 2009; Howe, Hoffman & Hardigree, 1994).

It is imperative for the management at H&M to investigate the expected outcome of each change before being implemented (Nonaka, 2001; Pettigrew, 2005). In addition, the individuals being affected by the very change should be brought into mind (Kanter, 1989; Pettigrew & Whipp, 2003; Deakins & Whittam, 2000).

Of all the changes undertaken by H&M from 2005 to 2010, employees were not held accountable or responsible in any of the changes implemented (Dawson, 1994; Finlay, 2000; Moran & Brightman, 2001; Ogbanna & Harris, 1998).

The main role of the H&M employees throughout this period was basically to act as instruments of change (Hope & Hendry, 1995; Johnson, 2007; Paton & McCalman, 2000; Pettinger, 2004).

In other words, they played the role of ensuring that the set objectives of the organization are met within the given time frame (Kotter, 1996; Lave & Wenger, 2006; Okumus & Hemmington, 1998).

Hence, both the executive officers and the overall management of an organization are the one charged with the responsibility of managing change within an organization (Nelson, 2003).

In the process of managing change, the latter ought to ensure that their employees are either in agreement with the said changes or can fully cope with them (Pareek, 2006; Parhizgar, 2002 ). The management at H&M should not be judgmental when implementing change.

This is well demonstrated in appendix B whereby radical changes within an organization can lead to instability due to likely resistance. The chart below illustrates the Grundy model and how the major types changes undertaken at H&M can affect the company.

From the figure above, it is evident that should the company opt to carry out ordinary changes in its operations, then it is highly likely to normalize its rate of growth.

The ‘smooth incremental’ line indicates that the changes being implemented y an organization do no result into major outcomes. For a company like H&M, a ‘bumpy incremental’ level is necessary to spur growth and outwit market rivals.

Fortunately, the company has been keen in all its major changes except in the 2005 resolution whereby it was proposed that shareholders present in Annual General Meetings were not permitted to participate.

Although this may have been taken in good faith, it is highly likely that some shareholders may not have been contented with the move, viewing it as a deliberate way of blocking them from airing their opinions on company affairs (Hughes, M 2010; Robbins, 2005).

The process of involving people when proposing change can be explained well using a model for change management principles (Beer & Nohria, 2000; Deal & Kennedy, 1988).

It is prudent for the management at H&M to continually involve and unanimously concur with those who are going to be affected by the changes within the system of the organization (Boisot, 1998; DeWit & Meyer, 2005).

The system of an organization comprises of quite a number of factors such as behaviors, relationships, culture, processes and the environment.

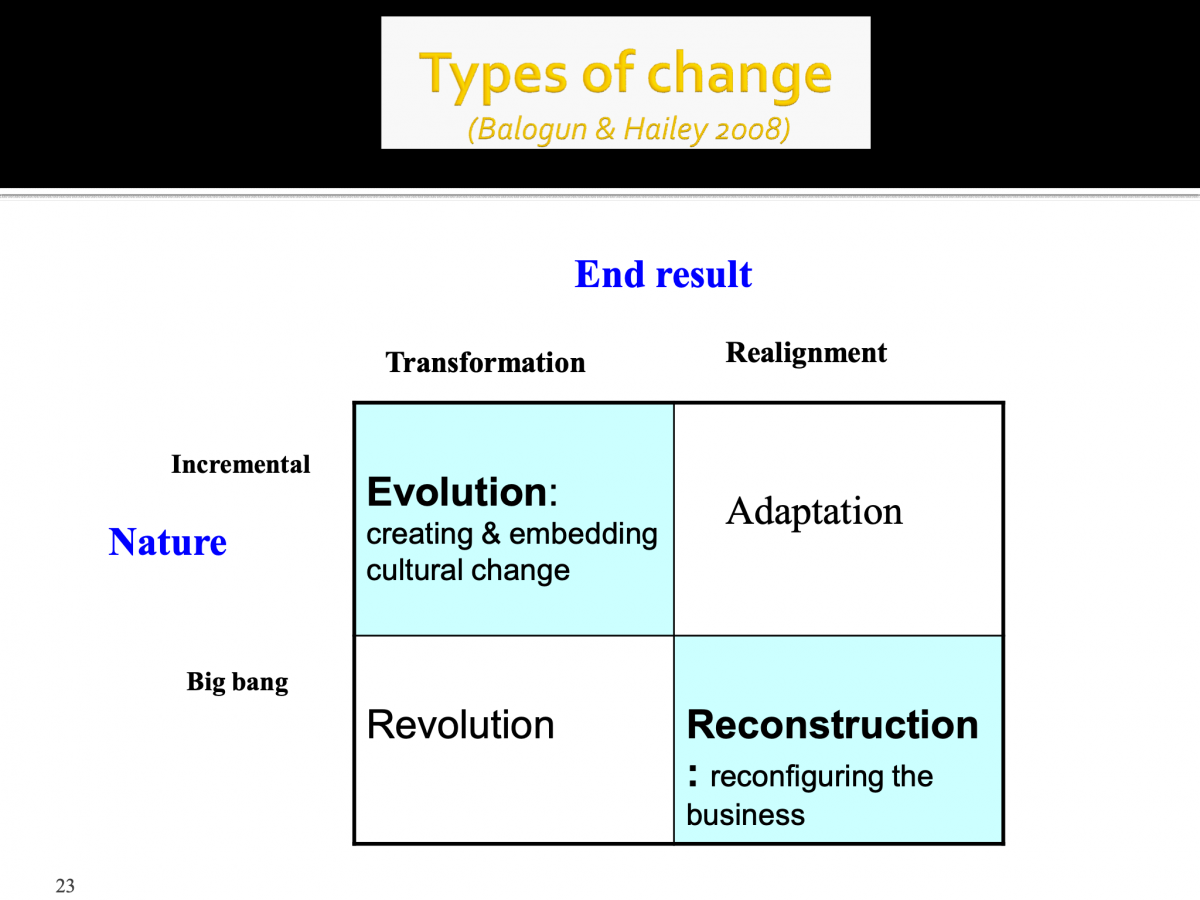

In respect to this model, it is pertinent for the management at H&M to fully understand the position of the company before implementing any change owing to the fact that an organization is comprised of several delicate elements that can be easily affected when slight changes are introduced (Balogun et al., 2008; Doyle, 2002; EldrodII & Tippett, 2002; Fletcher, 2004; Wilson,1992).

The change model by Kotter can be recapped as follows: People should be inspired when initiating change and this should be carried out as a matter of urgency. Second, a guiding team with the proper emotional commitment should be built. Third, the right vision should be adopted.

Fourth, it is important to communicate the basics concerning the change being implemented as well as removing obstacles that may jeopardize the process of change (Balogun & Johnson, 1998; Dunphy & Stace, 1993; Evans et al., 2002; Graetz, 2000).

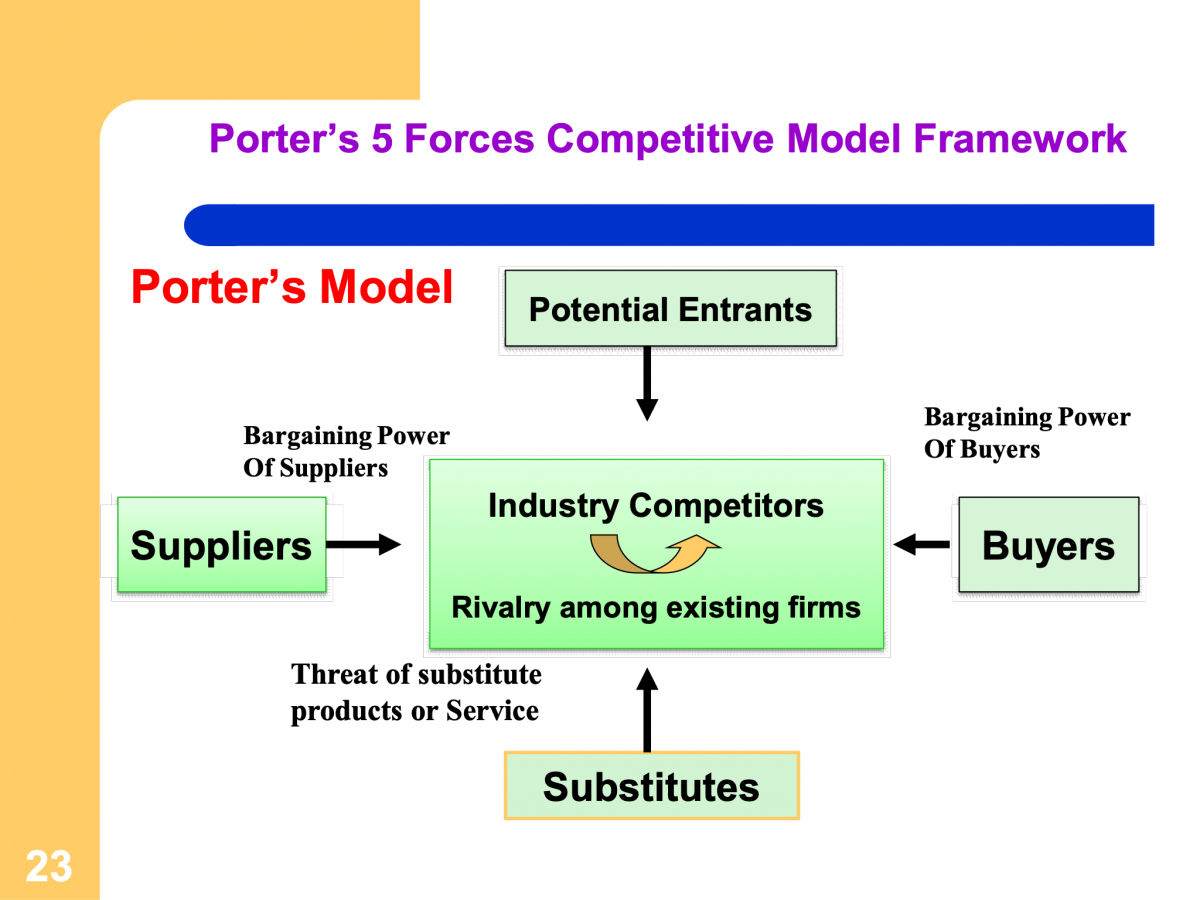

According to Porter’s Five Forces model, market competition is drieven by quite a number of both internal and external factors. For instance, potential entrants, buyers, sellers and substitute products are all threats brought about by competition.

Even as H&M implement various changes in its trading portfolio, the company should take into account the various elements that drive competition so that it does not lose out on its market share (Porter, 1998).

The figure below illustrates how competition is a vital factor to be considered when H&M is impplememting various changes withing its brand portfolio.

Conclusions and recommendations

H&M has been a key player in the clothing industry for decades now. The company deals in both men and women’s clothing and the related accessories such as handbags, shoes and under wears.

Since 2005, the company has undertaken myriad of changes in its trading portfolio as part and parcel of boosting its revenue growth. One of the notable changes at H&M has been the rapid geographic expansion of the company beyond its Sweden border (Guimaraes & Armstrong, 1998).

It currently, it operates several stores and outlets across India, China, Japan as well as several countries in Continental Europe.

Other outstanding changes since 2005 include massive collaborations with land mark designers, use of catalogue marketing and online shopping in some countries (Grundy, 1993; Guimaraes & Armstrong, 1998).

Facilitating these changes at H&M has been an uphill task. It is against this reason that proper change management procedures should be embraced by the company in order to yield the anticipated results.

Therefore, it is highly recommended that the company should seriously undertake evaluation and impact assessment in its day-to-day operations. Additionally, tracking down progress would require the use of key performance indicators.

Thus, H&M should enhance training and capacity building of its employees so that they are well equipped with the requisite skills and competences in carrying out their individual roles within the company.

Moreover, there should also be a well laid down framework for seeking solutions to workplace issues. Hence, worker representative’s platform should be strengthened by the company.

References

Balogun, J. & Johnson, G. 1998. Bridging the gap between intended and unintended change: the role of managerial sense making, New York: John Wiley.

Balogun, J. et al. 2008. Exploring Strategic Change, London: Prentice Hall.

Bamford, D. R. & Forrester, P.L. 2003. ‘Managing planned and emergent change within an operations management environment’ International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 23(5), 546–564.

Beer, M. & Nohria, N. 2000. Cracking the code of change. Harvard Business Review May-Jun, 133–141.

Boisot, M.H. 1998. Knowledge Assets: Securing Competitive Assets in the Information Economy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bond,T.C. 1999. ‘The role of performance measurement in continuous improvement’, International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 19(12), 1318-1334.

Boxall, B. P. et al. 2003. Strategy and Human Resource Management, Palgrave: Macmillan.

Bratton, J. & Gold, J. 2001. Human Resource Management: Theory and Practice, London: Macmillan Press Ltd.

Buchanan, D. & Badham, R. 2008. Power, Politics and Organizational Change, New York: Sage publications.

Bullock, R. J. & Batten, D. 2005. ‘It’s just a phase we’re going through: a review and synthesis of OD phase analysis’, Group and Organization Studies, 10(December), 383–412.

Burke, W. 2008. Organization Change, Theory & Practice, London: Sage publications.

Burnes, B. 1996. ‘No such thing as a “one best way” to manage organizational change’, Management Decision, 34(10), 11–18.

Burnes, B. 2000. Managing Change: a Strategic Approach to Organizational Dynamics. Harlow: Prentice Hall.

Burnes, B. 2004. Managing Change, London: Prentice Hall.

Burnes, B. 2004. Managing Change: A Strategic Approach to Organisational Dynamics, 4th edn Harlow: PrenticeHall.

Carnall, C. A. 2003. Managing Change in Organizations, 4th edn Harlow: PrenticeHall.

Clarke, M.I. 1985. The spatial organisation of multinational corporations, Sydney: Croom Helm Ltd.

Colville, I. et al. 1993. Developing and understanding cultural change in HM customs and excise: there is more to dancing that knowing the next steps. Public Administration 71, 549–566.

Davidson, M. C.G. & DeMarco, L. 1999.‘Corporate change: education as a catalyst’, International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 11(1), 16–23.

Dawson, P. 1994. Organizational Change: A Processual Approach. Paul Chapman Publishing Ltd, London. Henderson.

Dawson, P.1994. Organizational Change: AProcessual Approach London: Paul Chapman.

Deal, T. & Kennedy, A. 1988. Corporate Cultures, Boston: Penguin.

Deakins, D. & Whittam, G. 2000. “Business start-up: theory, practice and policy”, in Carter, S. and Jones-Evans, D. (Eds), Enterprise and Small Business: Principles, Practice and Policy, Financial Times, London: Prentice-Hall.

DeWit, B. & Meyer, R.2005. Strategy Synthesis: Resolving Strategy Paradoxes to Create Competitive Advantage, 2nd edn, London: Thomson Learning.

Doyle, M. 2002. ‘From change novice to change expert: Issues of learning, development and support’, Personnel Review, 31(4), 465–481.

Dunphy,D. & Stace, D.1993. ‘The strategic management of corporate change’, Human Relations, 46(8), 905–918.

EldrodII, P.D.& Tippett, D.D. 2002. ‘The “death valley” of change’, Journal of Organizational Change Management ,15(3), 273–291.

Evans, P. et al 2002. The Global Challenge, Frameworks for International Human Resource Management, London: McGraw-Hill.

Finlay, P. 2000. Strategic Management, New York: Pearson Education.

Fletcher, C. 2004. Appraisal and feedback: making performance review work, London: Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development.

Graetz, F. 2000.‘Strategic change leadership’, Management Decision, 38(8), 550– 562.

Grundy,T.(1993). Managing Strategic Change, London: Kogan Page.

Guimaraes, T. & Armstrong, C. 1998. ‘Empirically testing the impact of change management effectiveness on company performance’, European Journal of Innovation Management, 1(2), 74–84.

Guimaraes,T.& Armstrong, C. 1998.‘Empirically testing the impact of change management effectiveness on company performance’, European Journal of Innovation Management, 1(2), 74–84.

H&M. 2005. Corporate Governance Report 2005 Web.

H&M. 2008. H&M sustainability report 2008. Web.

Haas, J. R. & Hayes, S. C. 2006. “When knowing you are doing well hinders performance: Exploring the interaction between rules and feedback”, Journal of Organizational Behavior Management, 26: 91-112.

Hayes, J. 2002. Theory and Practice of Change Management, NJ: Macmillan. Health Manpower Management, 21(1), 16–19.

Henry J. et al. 2002. International edition, Managing Innovation and Change, London: Sage publications.

Hickson, D.J. & Pugh, D.K. 2005. Management Worldwide: The Impact of Societal Culture on Organizations Around the Globe, London: Penguin Books.

Hodgetts, R. et al. 2000. International Management, Boston: McGraw-Hill.

Holloway, S. 2002. Airlines: Managing to Make Money, Aldershot: Ashgate.

Hope, V. & Hendry, J. 1995. Corporate cultural change-Resource Management Journal 5(4), 61–74.

Howe, V., Hoffman, D.K. & Hardigree, D.W. 1994. ‘The relationship between ethical and customer-oriented service provider behaviors’, Journal of Business Ethics, 13(3), 497–506.

Hughes, M 2010. Change Management, A critical perspective. Indiana: CIPD.

Isabella, L.A. 2006. Evolving interpretations as change unfolds: how managers construe key organizational events. Academy of Management Journal 33(1), 7–41.

Johnson, G. (2007) Strategic Change and the Management Process.Basil Blackwell, Oxford.

Jones, O., Conway, S. & Steward, F. 2001. Social interaction and organisational change: Aston perspectives on Innovation Networks, London Imperial College Press.

Just-style.com. 2011. Analysis: H&M says it doesn’t need to smarten up to Zara. Web.

Kakabadse, A.; Bank, J. & Vinnicombe, S. 2004. Working in organizations, Burlington: Gower Publishing Company.

Kang, K., Oah, S., & Dickinson, A. M. 2003. The relative effects of differing frequencies of feedback on work performance: A simulation. Journal of Organizational Behavior Management, 23: 21-54.

Kanter, R. M. 2003. The Change Masters: Corporate Entrepreneurs at Work, London: International Thomson Business Press.

Kanter, R. M., Stein, B. A. & Jick, T.D. 1992. The Challenge of Organizational Change, New York: The Free Press.

Kanter, R.M. 1989. When Giants Learn to Dance: Mastering the Challenges of Strategy, Management, and Careers in the1990s, London: Routledge.

Katz, D. & Kahn, R.L. 2008. The Social Psychology of Organizations. John Wiley, New York.

Kogut, B. & Zander, U. 2002. Knowledge of the firm, combinative capabilities, and the replication of technology. Organization Science 3, 383–397.

Kotter, J. P. 1996. Leading Change, Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Lave, J. & Wenger, E. 2006. Legitimate Peripheral Participation.Cambridge: Cambridge University, Press.

Lee, G. 2003. Leadership coaching: from personal insight to organizational performance”, London: Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development.

Leifer, R. 2009. ‘Understanding organizational transformation using a dissipative structural model’, Human Relations, 42(10), 899–916.

Love, P. E. D., Gunasekaran, A. & Li, H. 2008. ‘Improving the competitiveness of manufacturing companies by continuous incremental change’, The TQM Magazine, 10(3), 177–185.

Luecke, R. (2003). Managing Change & Transition Boston, MA:Harvard Business School Press.

Lynch, R. 2003. Corporate Strategy, London: Prentice Hall.

Mayle, D. 2006. Managing Innovation & Change, CA: Sage Publications.

McKenna, F.E. 2000. Business psychology and organizational behavior, East Sussex: Psychology Press.

Moran, J. W. & Brightman, B. K. 2001. ‘Leading organizational change’, Career Development International, 6(2), 111–118.

Nelson, L. 2003. ‘A case study in organizational change: implications for theory’, The Learning Organization ,10(1),18–30.

Nonaka, I. & Takeuchi, H. 2005. The Knowledge-Creating Company. Oxford University Press, New York.

Nonaka, I. 2001. The knowledge creating company. Harvard Business Review Nov- Dec, 96–104.

Ogbanna, E. & Harris, L.C. 1998. Managing organizational culture: compliance or genuine change? British Journal of Management 9, 273-288.

Okumus, F. & Hemmington, N. 1998. ‘Barriers and resistance to change in hotel firms: an investigation at unit level’, International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 10(7), 283–288.

Pareek, U. (2006). Organizational Leadership and Power, Punjagutta: ICFAI University Press.

Parhizgar, D.K. 2002. Multicultural behavior and global business environments. New York: International Business Press.

Paton, R. A. & McCalman, J. 2000. Change Management: A Guide to Effective Implementation, 2nd edn, London: SAGE Publications.

Patton, R. & McCalman, J. 2008.Change Management, A guide to Effective Implementation, NJ: Sage Publications.

Peper, B. et al. 2005. Flexible working and organisational change: the integration of work and personal life, Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing Ltd.

Pettigrew, A. M. & Whipp, R. 2003. Managing Change for Competitive Success, Cambridge: Blackwell.

Pettigrew, A.M. 2005. The Awakening Giant: Continuity and Change in ICI. Blackwell, Oxford.

Pettinger, R. 2004. Contemporary Strategic Management Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan.

Porter, E.M. 1998. Competitive strategy: techniques for analyzing industries and competitors, New York: The Free press.

Raney, M. & Clark, K.B. 2010. Architectural innovation: the reconfiguration of existing product technologies and the failure of established firms. Administrative Science Quarterly 35, 9–30.

Ricketts, J.M. 2002. The economics of business enterprise: an introduction to economic organization and theory of the firm, Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing Ltd.

Rieley, J. B. & Clarkson, I. 2001. ‘The impact of change on performance’, Journal of Change Management, 2(2), 160–172.

Robbins, P.S. 2009. Organisational behaviour: global and Southern African perspectives, Cape Town: Pearson Education Inc.

Robbins, S. 2005. Essentials of Organisational Behaviour, Indiana: Pearson Education.

Salaman, G. & Asch, D. 2003. “Strategy and capability: sustaining organisational change”, Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

Salaman, G., Storey, J. & Billsberry, J. (2005). Strategic human resource management: theory and practice, London: Sage Publications.

Sathe, V. 2003. Implications of corporate culture: a manager’s guide to action. Organization Dynamics Autumn, 5–23.

Schuler, S. R. and Jackson, E. S. 2007. Strategic human resource management, Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

Senior, B. & Swailes, S. 2010. Organizational Change, New York: Prentice Hall.

Sinclair-Hunt, M. & Simms, H. 2005. “Organisational Behaviour and Change Management”, Cambridge: Select Knowledge Ltd.

Storey, S. 2004. Leadership in organizations: current issues and key trends, New York: Routledge.

Tate, W. 2009. The search for leadership: An organisational perspective, Devon: Triarchy Press.

Wilson, D.C. 1992. A Strategy for Change, New York: Routledge.