Abstract

In the 21st century, China has popped up as a big tourism country worldwide. China’s tourism business has been around in various countries and regions, forming a large industrial scale. The tourism industry, like a sunrise industry, with its own unique properties, has a great potential in stimulating consumption, accepting employment, promoting industrial restructuring and economic development.

This paper analyzes the general theory of tourism enterprises through the historical inevitability of conglomeration of tourism enterprises, the development status of tourism in China and other developed countries and internal and external barriers of China’s tourism enterprises. The aim of this paper was to reveal the Chinese tourism enterprises development strategy, to promote China’s tourism business a faster and healthier development, in order to deal with international competition and challenges. Primary data was collected using questionnaires and analyzed using statistical techniques.

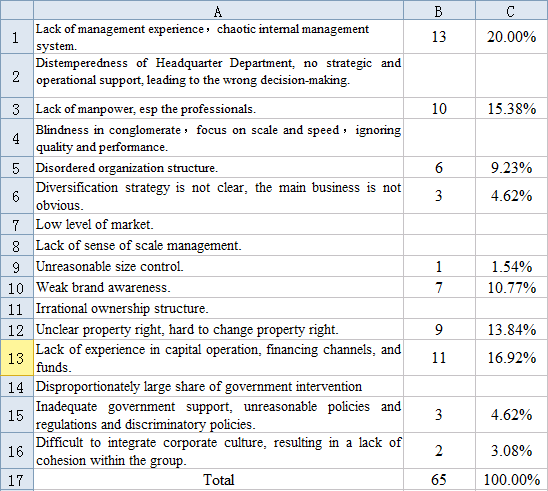

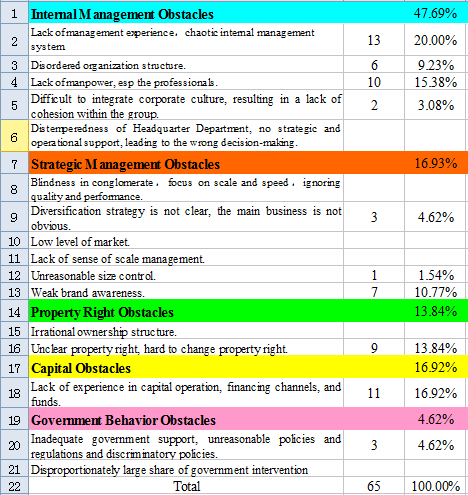

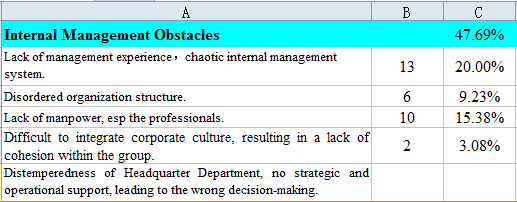

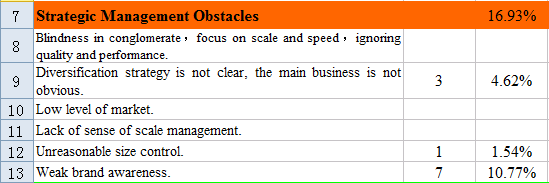

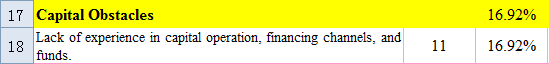

The study found out that the major obstacles to conglomerate development are: lack of management experience, lack of experience in capital operation, financing channels, and funds, lack of manpower, unclear property right and weak brand awareness.

Introduction

Overview

This chapter covers the background to the study, problem statement, research objectives, research hypotheses and the significance of the study.

Background to the study

According to the statistics of World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) and World Travel and Tourism Council (WTTC), in the next 10 years, as the world’s largest industry, the global tourism industry will grow by more than 4.4 per cent annually, the number of international tourists and international tourism revenue is postulated to expand by between 4.3 per cent and 6.7 per cent annually; this is far much higher than the 3 per cent of world’s wealth increasing rate (World Travel and Tourism Council 2011). By 2020, tourist arrivals worldwide are expected to reach 1.6 billion passengers; the tourism industry revenue will increase to 16 trillion dollars, which is equivalent to 10 per cent of the global GDP. At least 300 million jobs will be provided, accounting for 9.2 per cent of the total global employment, further strengthening its position as the world’s largest industry (Shiwen 2008, p.23). According to the World Tourism Organization, the global financial crisis in the US and Europe crippled tourism market in mature economies, tourism in emerging economies is still developing. The tourism industry has become the first industry to rebound in the international financial crisis. It contributes to reducing the negative impact of the crisis and plays an active role in the global economic recovery (World Travel and Tourism Council 2011).

Since the occurrence of the global economic crisis, China’s tourism industry continued to maintain the momentum of rapid development. Its international tourism ranked first in Asia in addition to a strong tourism growth domestically (Shiwen 2008, p.25; Sorensen 2004, p.19). There are at least 20,000 travel agencies, 14,000-star hotels, 18,500 tourist attractions and 1.350 million practitioners. In 2010, China’s domestic tourism revenue was 1.26 trillion Yuan (equivalent to £ 117.3 billion), increasing by 23.5 per cent; tourism foreign exchange revenues was $45.8 billion, increasing by 15.5 per cent; China’s total tourism income was 1.57 trillion Yuan (equivalent to £146.15 billion), increasing by 21.7 per cent, equivalent to 3.94 per cent of China’s GDP. The tourism industry, as a new economic growth point, has been further strengthened (China National Tourism Administration 2010).

However, the data above only shows that China is a big tourist destination, not a destination with powerful competitiveness. China has a long way to go on the efficiency of resource allocation and competitiveness of tourism enterprises as compared with the other developed countries (Southall 1998, p.262). In terms of the overall economic benefits since the 1990s, there were two distinct characteristics: at the macro level, entailing that the industrial system and the size of the market are growing rapidly; at the micro-level, entailing that the total number of enterprises and incomes are increasing, the total profits and profit margins of tourism are declining even to negative profit margins and zero profit, thus, the tourism market as whole marks a poor performance (Leslie 2009, p.34; Tang 2005, p.332). China’s tourism market performance is summarized in Table 1.1 below.

Table 1.1 Performance of China’s tourism market. Source: (He & Xu 2007, p.53).

According to the structure conduct performance model of industrial organization, market structure determines market behaviour, and market behaviour has further affected the market performance (Bain 1968, p.122; Unger & Chan1994, p.37). Therefore, the poor performance of the Chinese tourism market can be attributed to the market structure. Table 1.2 shows the characteristics of China’s tourism market structure.

Table 1.2 China’s tourism market structure. Source: (He and Xu, 2007, p.54).

The table above depicts that China’s tourism enterprises have not become a real mainstay of the market, with small scale and low competitiveness. In the tourism industry, against the backdrop of market expanding, while the overall effectiveness growing, the acceleration is sluggish, resources allocation is inefficient, and the market performance is poor (He & Xu 2007, p.54; Wang 2003, p.334).

Statement of the problem

The relatively good performance of the tourism market in developed countries is because of the existence of some large travel companies, such as JTB in Japan, TUI in Germany, Thomas Cook in the UK, and American Express in the US (Wang 1995, p.62; Wang 2003, p.55). According to the annual reports before the outbreak of the economic crisis, in 2007 the operating income of JTB was $11.6 billion; it owned 338 offices, 2,500 branch offices and 66 international branches; In 2007, TUI’s Revenue was €21.865 billion, owning 797 branches, 3,500 travel agencies, 285 hotels and more than 100 aircraft; Thomas Cook in 2007, had an operating income of 64.06 GBP, owning 3600 agents worldwide, 85 aircraft and 73,000 beds in different hotels; In 2007, American Express had tourism-related revenues of $24.6 billion and 1,700 offices in 130 countries worldwide; currently the American express card owns 51.7 million users including 33 million US users (Leslie 2009, p.36; Wu 2003, p.42).

China is a major tourist destination with development potential; China is a big tourist destination, not a destination with powerful competitiveness (Wu 2002, p.1081). China has a long way to go on the efficiency of resource allocation and competitiveness of tourism enterprises as compared with the other developed countries. Potential converting into real productivity needs to establish a number of powerful national or multinational levelled enterprises with international competitiveness (He & Xu 2007, p.57; Wu & Yeh 2007, p.122). Increasing Chinese tourism market performance should be attributed to improving tourism market structure, forming large scale tourism enterprises, improving the correlation of assets in the tourism industry, optimizing the industrial structure, regulating the tourism market behaviour and ordering market competition (Wu & Ma 2005, p.268; Yin & Wang 2000, p.157). The development of enterprise conglomeration is the only way for China’s tourism.

Objectives of the study

The general objective of this study was to explore the development and management of conglomerated Chinese tourism enterprises. In line with the general objective, the study further examined the following specific objectives:

- To verify the effect of internal management on the development of tourism enterprise conglomeration;

- To investigate the effect of strategic management on the development of tourism enterprise conglomeration;

- To find out the influence of property rights on the development of tourism enterprise conglomeration;

- To determine the effect of capital structure on the development of tourism enterprise conglomeration;

- To determine the influence of government behaviour on the development of tourism enterprise conglomeration;

- To find out the solutions to the obstacles of the conglomeration of Chinese tourism enterprise.

Research Hypotheses

In order to meet the above objectives, the following hypotheses were tested:

- Ho1: Internal management does not affect the development of tourism enterprise conglomeration;

- Ho2: Strategic management does not affect the development of tourism enterprise conglomeration;

- Ho3: Property rights do not affect the development of tourism enterprise conglomeration;

- Ho4: Capital structure does not affect the development of tourism enterprise conglomeration;

- Ho5: Government behaviour does not affect the development of tourism enterprise conglomeration;

- Ho6: There are no solutions to the obstacles of the conglomeration of Chinese tourism enterprise.

Justification of the Study

The findings of this study are of great value to policymakers and regulatory authorities. It provides the policymakers with a wide exposure with regard to the development and management of the conglomeration of Chinese tourism enterprise; thus, enabling them to adopt the relevant strategies in line with the situation. The findings of this study also add to the body of knowledge of related studies about the conglomeration of Chinese tourism.

Scope of the Study

The scope of this study was in line with the general objective, which was to explore the development and management of the conglomerated Chinese tourism enterprises. Using primary data and applying statistical techniques, the study explained the variables to meet the research objectives.

Literature Review

Introduction

This chapter reviews the theories both empirical and theoretical that are closely linked to the development and management of Chinese tourism enterprise conglomerating. This literature review is based on the research proposal submitted in May 2011.

Tourism groups

The classification of tourism groups

From different contexts, tourism enterprise groups can have several categorizations. According to the formation patterns, they can be divided into four types, market growth types, industry-oriented types, capital intervention types and government-driven ones (Gee 1988, p.35; Yeung & Lo 1998, p.141). By business growth directions, that is, according to diversified development directions, tourism enterprise can be divided into three categories: (a) Horizontal specialization, meaning the tourism enterprise group will devote all its efforts to producing a single product and expanding in a single market; (b) Vertical integration, meaning the group will make expansion at the different stages of production; (c) Diversification, meaning that the group will make expansion at different areas with different final products (McGuffie 1996, p.36; Ansoff 1965, p.218; Yuann & Inch 2008, p.220). According to different affiliation models and structural relations, tourism enterprise can be divided into five forms, for instance: groups owned by a company, groups with holdings controlled by companies, groups leased by companies, management contracts and franchise alienation. In practice, these five forms are not separated from one another but are usually used in a mixed way (Harrison & Enz 2005, p.118; Yusuf & Nabeshima 2008, p. 35).

According to the formation of hotel groups, tourism enterprise can be divided into three types: (a) Chain, refers to a form of operation in which two or more subsidiaries operate under the same parent company which controls them through the complete ownership and lease of their buildings or land (Rousselle & Adler 2000, p.112); (b) Franchise, refers to a sustained relationship in which certain franchise rights are granted to the grantees, and the grantees get support in terms of organization, operation and management and in turn they return with some rewards (Barrows 2008, p.205; Yusuf & Wu 1997, p.202); (c) Management Contracts, also known as trustee management, means that the owners entrust their businesses to a management company (Diaz 1999, p.120).

According to the different driving forces and bonding relationships, the growth of the conglomeration of Chinese tourism enterprises can be divided into the following 4 models: (a) The tourism enterprises are driven by the government to voluntarily or involuntarily build an enterprise group with cooperation as the main objective, such as China Lianyi Group, China Hualong Group and China Friendship Group; (b) The groups are founded by a regional government with assets as the tie between different enterprises; (c) The hotel groups are built by the big companies or groups without the tourism industry, such as Gloria Hotels & Resorts and HNA Group; (d) The regional tourism groups are founded through the allocation of state-owned assets (Gu & Qin 2001, p.1; Cheng & Mark 1994, p.650). With regard to the geographical locations, tourism enterprise can be divided into domestic and international tourism groups (Luo 1997, p.1; Bairoch 1991, p.280).

Competitive advantages of the tourism group

Tourism enterprises engaging in a single business are willing to join a group because the tourism group has unique advantages in management and market expansion ever since its birth (Gee 1994, p.201). Tourism groups have various advantages with regard to management; the groups adopt the unified organizational structure, systems and management standards (Leslie 2009, p.102). The hotel groups in developed countries can adjust their organizational structures in line with the group size as well as their businesses; thus, giving a better contribution to the scale effect of the group (Myers 1996, p.47; Beall 2000, p. 430). These hotel groups generally have more advanced and well-developed management systems, which can establish uniform management methods and procedures for hotels under their control. And these hotel groups also can provide support for the hotels they are in charge of in various aspects including management. Largest hotel groups also provide train programs for the hotel staff.

The group has the ability to provide a variety of technical services and assistance to the affiliated hotels (Pizam 2005, p.113). In addition, the tourist groups have a financial strength; joining the group can help build up the credit of an enterprise in the eyes of the financial institutions, thus, making it easier to get a loan from them (Bloom & Williamson 1998, p.432; Ebrey 1996, p.175). Meanwhile, the group can also provide its affiliated enterprises with information about the financial institutions and recommend lending institutions to them (Andrew & Damitio 1993, p.207). The group has a strong internal financial regulation and control and can regulate the fund surplus and deficiency of its affiliated hotels in a timely manner (Horner & Swarbrooke 2004, p.302). Through the approaches such as scale operation and unified procurement, the group can effectively reduce the operating costs (Leslie 2009, p.102).

The tourist groups also have marketing advantages that are beneficial to them; the unified group sales and online bookings can build a solid customer base for hotels and tourism enterprises (Leslie 2009, p.122). The groups are usually large in scale and success in business and enjoy a high reputation, which is extremely beneficial to their promotion efforts (Wang 1999, p.13). A well known international hotel group with a high standard of service is sure to be attractive to the customers (Dubé & Renaghan 2000, p.68; Prahalad & Hamel 1990, p.12). A group can pool funds to engage in a large scale and worldwide advertising promotion, such as the Hilton Group’s worldwide promotional campaigns that honours promotion programs, senior citizens targeted tourism promotion programs, and weekend holiday promotion programs (Huckestein & Duboff 1999, p.32).

The tourist groups have advantages with regard to government policies; in China, a tourism group can enjoy many state preferential policies. As the related stipulations of State Council and National Tourism Administration (SCNTA) express in explicit terms that: in order to support the development of China’s domestic hotel management companies, in principle, the domestic hotel groups will be treated as equals as their foreign counterparts in China (Horner & Swarbrooke, 2004, p.204). The tourism groups also have advantages in terms of accessing information; the member enterprises of the group collect a large amount of information during the process of production, management and distribution. Through the exchange and sharing of the information, a greater value of the information is realized (Downie 1997, p.14). The tourism groups in developed countries attach much importance to the analysis of economic data and over the years they have gained much experience in processing information and improving the efficiency of decision making (Litteljohn 1985, p.162).

Connected assumptions of tourism groups

The conglomeration of tourism enterprises can be related to all aspects of enterprises behaviour. Therefore, the research needs to refer to the existing theories, especially on the organizational structure of the enterprise, strategic management theory (including the theory of competitive strategy and entrepreneurship theory), the modern theory of the firm (including property rights theory, contract theory and transaction cost theory), the theory of corporate culture, organizational learning theory, human capital theory and the theory of knowledge management support. These theories are not for tourist enterprise group to study itself, but it is necessary for the research of the conglomeration of tourism enterprises (Girardet 2004, p.168).

The assumption of the assortment of businesses

With the development of enterprise groups in developed countries, many lessons have been learned over the years. The mainstream thinking of both the business community and academic circles in the diversification of the growth of the enterprise groups is that a diversified development centring on core business is the guarantee for the success of a group. The representative theory is stated in the book of “Corporate-level Strategy” co-written by the British scholars representative Michael Goold, Andrew Campbell and Marcus Alexander in 1994. Their theory is based on the theories of their predecessors and the facts of the diversified development of large enterprise groups. They hold that: “if the company level strategies are expected to achieve the value-added purpose, the parent organization must build a high synergy and coordination with its operating divisions. A successful parent company is only devoted to a relatively narrow business scope but can always create value in these areas” (Goold, Campbell & Alexander 1994, p.137).

The assumption of organizational design of businesses

In the course of economic development, many different organizational structures emerged, such as the traditional line structure, functional structure, unitary structure and line and staff structure as well as modern multidivisional structure, matrix structure, multidimensional structure and holding structure. Of all these different structures, there are two most basic and common ones. One of them is the highly centralized unitary structure and the other one is a multidivisional structure (also known branching structure), which is widely used in modern enterprises. As Chandler (1962, p.134) said, many different variants of the organizational structures were developed and in recent years, now and then some variants were combined with each other to develop a new structure. Despite all of this, there are still only two basic organizational structures in the management of large enterprises: the centralized structure with function-based departments and the decentralized structure with multiple branches. The features of these two organizational structures are as follows:

Unitary design

The management design takes the British classical economists Adam Smith’s assumption of the division of labour as the core principles of organizational structure; thus, creating a business design in which the supreme leader has the absolute dominance. U-form organizational structure is shown in Figure 2.1:

This kind of company has various basic features based on the different functions; the company is divided into different management departments including production, marketing, technological development and financial accounting; each department is supervised by the company’s most senior leaders (and the important posts of the senior managers are usually held by private owners or major shareholders). Unitary Structure is an organizational structure which realizes a high degree of centralization (Litteljohn 1985, p.162; Sorensen 2004, p.22).

Multidivisional design

Multidivisional design is a combination of centralized and decentralized forms of organizational innovation. Often different divisions are set up according to different products, regions or countries and unitary structure is adopted in every division. The headquarters of the enterprise grants a great operational autonomy to its divisions, thus enabling them to do business in line with the market situation just like an independent company. Under every division, there are various management departments, such as production, marketing, development, and financial accounting. Every division is independent in accounting and responsible for its own profits and losses (Tang 2005, p.132; Unger & Chan 1994, p.50).

Such an organizational structure makes the company headquarters free of heavy daily businesses. It allows the headquarters to focus more on formulating and implementing strategies and plays the most important role of coordination and supervision. Thus, it can contribute to solving of problems within a large enterprise, such as product diversification, product design, information transfer and the coordination of decision making between different divisions (Wu 2002, p.1077; Yuann & Inch 2998, p.108). A strategic planning department is set up under the headquarters, and sometimes other functional departments such as finance department, accounting department and human resources department will also be established, which will provide guidance, services and consultations. It can keep the senior management personnel free of the trivial matters in daily businesses and allows them to maintain extensive contacts with their affiliated enterprises. At the same time, it also lowers the transaction costs within the enterprise. That is why the multidivisional structure is so widely adopted by so many enterprises. M-form organizational design is shown in Figure 2.2.

M-form structure has always been considered as a very suitable organizational structure at this stage for large enterprise groups. In the 60s, the US management expert Alfred Chandler (1962, p.218) published the book “Strategy and Structure”. In the book, he concluded that the surge of the production line of an enterprise leads to its changes in organizational structure, namely, the change from a functional and unitary structure to a loose multidivisional structure. In the 60s and 70s, his theory exerted a profound influence on the trend of decentralized operation of the large organizations (Chandler 1962, p.218).

During the 80s, with the further development of enterprise groups, new theory in terms of the organizational structure of enterprise groups emerged. The most representative theory was proposed by Christopher Barllett and Sumantra Ghoshal (1989) in their book “Managing across Borders”. In the book, they argued that a company can choose among the different organizational structures in light of the actual needs and they did not have to choose between the two extremes of the previous organizational structures, that is, centralization or decentralization. And they also developed a new organizational structure – Entrepreneur Structure.

It had three core functions: (a) promoting entrepreneurship, (b) paying attention to the outside world, and (c) seeking business opportunities. Functional integration enables the company to make full use of dispersed resources and capabilities and then build a successful business. Updated functions allow companies to constantly examine their current beliefs and practices. Thus, it will inject new impetus into the enterprise and sustain its development. But at the same time, they also admitted that multidivisional structure has completely replaced the functional structure which poses many limitations and the multidivisional structure may be the only or the most important reform in management which can help an enterprise in its expansion and diversification (Bartlett & Ghoshal 1989, p.211; Yusuf & Wu 1997, p.76).

Competitive advantage

The conglomeration of tourism enterprises nowadays is a development direction. In the modern strategic management theory, the theory of competitive strategy proposed by Michael Porter (1983, p.171) and the capacity of enterprises theory (enterprise resource theory) rise in the 90s stand out and provide an important starting point for this research. The conglomeration of tourism enterprises enhances competitiveness and creates a competitive advantage. The reason is that in the process of conglomeration, the old capacity reinforces and new capacity accumulates which helps the companies to develop and implement effective market competition strategies (Cheng & Mark 1994, p.653).

Competitive strategy theory of Michael Porter

Michael Porter’s (1983, p.49) theory of competitive strategy demonstrates that competitive advantage comes from the market force company-owned, which allows the enterprise to influence the industrial structure in order to gain competitive advantage within the industry. From Porter (1983, p.49), enterprises can choose “cost reduction”, “differentiation” and “target gathering”; three basic strategies to obtain its market advantage. On how to implement the strategy, Porter (1983, p.49) proposed a value chain concept. According to the definition, a company’s business can be described as a value chain; the total revenue from products or services activities minus total expenditure is the value-added from the chain. As long as the total income brought by products and services exceeds total expenditure, the company earns. Thus, by value chain analysis, companies can improve the value chain activities so as to improve its profitability (Porter 1983, p.50). From this point of view, the aim of conglomeration is to make the industrial environment under control through forming a corporative group. When the major companies from the developed world entered China, the only reaction for the local companies was to enlarge the company scale and enhance its influence in the industry (Bloom & Williamson 1998, p.423; Wu 2002, p.1090; Unger & Chan, 1994, p.37).

Capacity of enterprises assumptions

The capacity of enterprises theory believes that an enterprise is a collection of capacity or resources. And the keys to keep the competitive advantage are the capacity to accumulate, keep and apply a market expanding power. From this perspective, rather than the external environment, the internal one is a necessity to acquire and keep the competitive advantages (Sorensen 2004, p.23; Tauber 1981, p.38). And the capacity and resource are the sources of power. Differences in capacity lead to differences in performance. Since the capacity determines the performance and the competitive advantage, the capacity not only decides the sphere of business, especially the breadth and depth of its business diversification but also influences or even determines the performance of conglomeration. As for the conglomeration of tourism enterprises, core enterprises’ ability to acquire and integrate determines the performance of conglomeration (Prahalad & Hamel 1990, p.24). Some corporate groups kneaded by government administration do not play well because of a lack of the ability to acquire and integrate.

Therefore, in the process of the conglomeration of tourism enterprises, the ability of integration must be injected. The injection mode ranges from choosing the company with the ability as a core company or hiring the senior management personnel who can train staff to acquire this ability quickly as a group leader. Therefore, the competitive advantage can be established and the competitiveness of the enterprise can be increased (Prahalad & Hamel 1990, p.24; Ruan 2000, p.57).

Modern assumptions of enterprises

The modern theory of enterprise is mainly made up of property rights theory, transaction cost theory, and principal-agent theory as the main content. The modern theory of enterprise considers the enterprise as “a joint of a series of contracts”, which means that enterprise is a way of transactions between property (including substance resources and human resources) owners. The size of enterprises depends on the comparison between the internal cost of management and coordination and external cost of transaction in the market. The reason for tourism enterprises to conglomerate is because of the fact that the cost of internal property flow is much lower in the group than the external market transaction costs (Coase 1937, p.128; Ross 1973, p.138).

From the point of view of the modern theory of enterprise management, we can have a more complete understanding of the property relations: firstly, in the process of conglomeration, the property’s main body (including the main body of substance resources and human resources) will terminate or modify the original treaty or conclude a new treaty through equal gambling (Ross 1973, p.136). Corporate groups are not only involved adjusting the relationship among investors – the shareholders of the corporate group – but also among all parts of stakeholders (including shareholders, employees, suppliers, distributors, consumers and local residents, etc) (Clarkson 1995, p.103).

We cannot simply understand the conglomeration as the allocation of assets among tourism enterprises or the establishment of a cooperative relationship. Secondly, taking an enterprise as a joint of contracts has a preposition, which implies that the parties in the contract are supposed to be independent and share the equal property main bodies. A one-sided emphasis on one party’s interests is inconsistent with the principle of fairness embedded in the free market economy (Coase 1937, p.132). Therefore, in the process of conglomeration, we cannot rule out the equal participation of stakeholders, despite the fact that their interests are dissimilar. Otherwise, when they realize that their own interests are damaged by the process of conglomeration, they will take an uncooperative attitude, which is detrimental to the group’s development (Rousselle & Adler 2000, p.112; O’Neill & Mattila 2006, p.148).

Finally, due to the incompleteness of the contract, the operation of the enterprise relies heavily on the implications that exist in a variety of aspects, and it is far more complex to adjust these implications than the written contract since they are actually an adjustment of enterprise culture. The enterprise culture, as an implicit contract, can be seen as a complement of the written contract, performing a transaction cost-saving function (Liu & Dong 2001, p.132; He & Xu 2007, p.55). Therefore, in the process of conglomeration, the management of enterprise culture must be strengthened, and gradually a complete and optimized enterprise culture can come into existence (Ross 1973, p.137).

Brand and the brand extension assumptions

The assumption of corporate brand

The famous marketing guru Philip Kotler (1997, p.201) has a well-known definition of a brand; a brand is a name, term, sign, symbol or design, or a combination of them, and its aim is to mark a particular seller or group of sellers’ products or services in order to make it distinctive from the competitors’ products. A brand is a symbol or attitude of choices embedded in the minds of consumers; meanwhile, it is a feeling (Kotler 1997, p.201; Harrigan 1987, p.67). Tourism Group’s brand has the general content of the brand, which contains the names, symbols, designs, and combinations of them for tourism products or services to be distinguished, through the tourists’ experience; hence, bringing extra profits for the company. But the tourism product is different from the tangible ones, after the conglomeration, the brand design, promotion, extension and adjustment of all aspects should bear their own characteristics (Kotler Bowen & Makens 2006, p.135). Existing research shows that, for tangible products, the brand is the most important, while for intangible services the brand is the first (Kotler 1997, p.200).

The assumption of brand extension

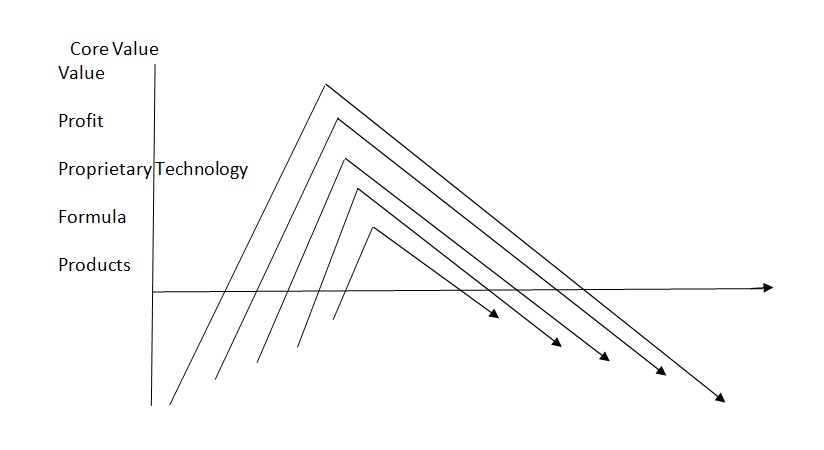

The most important step of brand management in the process of tourism enterprises is how to do the brand extension on the basis of the original brand. Brand extension refers to a strategy of transplanting a famous or successful brand to different products, using the influence of the brand’s existing market power to launch new products to form a series of the product (Tauber 1981, p.38; Dussauge & Garrette 1995, p.515). The most important thing is that the extended products need to fit the core value of the brand. The brand’s core value, in essence, refers to the impression of the brand and symbolic meaning left in the minds of consumers, rather than the specific use of the product. When conducting a brand extension, the existing brand positioning needs to be analyzed. In addition, the brand’s core values should support the brand extension. It is also essential to pay attention to the extent to which the extension should be supported (Kapferer 2000, p.213). In other words, the content of core value determines the extension potential – the model released by Jean-Noël Kapferer (2000, p.214) is as followed.

The model shows that if a core brand value relates to the product-specific functions, formulas, technology, etc., then the extension potential of the brand is very limited. Conversely, if a brand’s core value has nothing to do with the product attributes and product technology, then it provides benefits to the consumers and adds values of the brand. When the brand extension potential is large, the brand is said to be highly extensible. To enhance the brand extension power, the concept of the brand needs to switch from the product formula to proprietary technology, interests and values. It also shows that to make a brand covering more types of products, the brand must have a deeper meaning. If a brand has no other identifying elements apart from the material properties (product or formula), then it cannot support a wide range of extension (Kapferer 2000, p.33).

We can use this figure to analyze the extension capabilities of a certain number of well-known brands. The possibility of brand extension depends largely on whether the original brand’s core values are transferred to the extended products truly and completely. Particular formula and techniques are usually closely associated with certain products, it is difficult to extend it to a new product; on the contrary, brand philosophy and brand benefits for consumers are relatively easy to transfer to the new products, which will greatly enhance the ability of brand extension. In other words, the content of the brand’s core values determine the feasibility and scale of the brand extension capacity and it is the key factor whether the brand can be extended and to what extent it extends to (Prahalad & Hamel 1990, p.24; Ruan 2000, p.57).

Travel agency and brand extension work in such a way that after a successful launch of a brand or a product, the products are developed under this brand and the product lines are extended form a series of relevant brand products. Some of the successful tourism enterprises through long term development and marketing capabilities grew rapidly. Internally, it also formed a mature marketing team with marketing experience and sales network. In this case, the brand extension strategy can not only provide consumers with more choices and improve the brand’s market competitiveness but also reduce the marketing costs for each product under the brand (Leslie 2009, p.102). However, the enterprises should deal with the relationship between the extension of products and the original brand. The core brand extension should not compromise the quality of the original brand and its customers’ experiences.

Therefore, the travel agency could apply sub-brand or multi-brand strategy, drawing attention to the link of original products, such as the similar service system, same interest points, same culture and value or a similar target market, etc., then take advantage of the product links and integrate the entire product line naturally, without any far fetched senses. For example, under the “new world view” brand launched by Shenzhen CITS, “finding the source” by Shangri-La, “thousands of elderly to Hong Kong and Macao go hand in hand” and “Shenzhen couple, Yangshuo appointment” are all-star products. Although they have different target markets, all of them reflect the humane and personalized content (Leslie 2009, p.102).

Assumption of Business Process Reengineering

Business Process Re-engineering (BPR) is an innovative approach to business organization born in the early 90s, in the USA. It was firstly advocated for by Professor Dr Michael Hammer, a former computer professor of Massachusetts Institute of Technology; the theory was further promoted by him. The term “re-engineering” was created by Dr Hammer. Re-engineering means the use of modern information technology to re-design business process fundamentally in attempts to improve their performance (Hammer & Champy 1993, p.90).

A process is a series of logically ordered sets of activities for a goal or a task. Business activities can be integrated into two different ways. One is according to the similarity of activities, such as combining similar activities into functional groups, like establishing a sales department; the other way is by engaging related activities together to form a process-oriented group, such as collecting personnel of design, technique, production, testing together to form a product development group. In a functional group, members assume the same job, thus the enterprise could gain the labour efficiency of division and economies of scale, but completing a workflow needs cooperation across multiple functional departments.

For example, in a manufacturing enterprise, the implementation of customer orders need to go through sales, production, finance and several other departments, so that the entire business process has to be separated by several units. Each functional department is engaged in one part of a complete process, while another part takes responsibilities of its own. As a result, the work of one part may be effective, but the operation of the entire process is inefficient. Each process is irresponsible for the overall concept, so the employees do not care about the development of the enterprise, and the lack of innovation, passion and enthusiasm, eventually leading to a lack of organizational ability to respond to the change of environment. While in the process groups, the group members are engaged in different but linked activities (Leslie 2009, p.102). Each member may be an expert in a certain field; their participation can make the work quickly resolved. The communication and coordination among them are rapid and efficient, thus they can complete the work efficiently and have a quick response to the outside world (Hammer & Champy 1993, p.91).

In the process-based organization, its operation is no longer on the basis of functional units, but on the process working groups, composed of employees who are working together and implementing the whole process operation. In general, this process group is usually seen in three basic forms: the first one is a group consisting of people of different skills together, they work together to accomplish a complex task. The second is the virtual working group, which is based on special needs or a specific task. Third, is the project worker, which is similar to the first one, but has only one member (Hammer & Champy 1993, p.91).

For service-oriented industry, the process of re-engineering is important. After the conglomeration of tourism enterprises, the environment will be changed dramatically, and this change is often a qualitative one, which means that after conglomeration, tourism enterprises need to redesign their business processes. For example, when travel agents conglomerate across regions, the business among regions can be achieved through the network, thus many processes can be simplified.

Management of tourism enterprise conglomeration

Developed countries started early in tourism groups. Their tourism groups outweigh China’s tourism by far in terms of size, capacity and effectiveness of the expansion means, which can be seen from the following data: Tourism groups in developed countries are very large in scale and have a high concentration. In 1995, the tourism-related business of American Express accounted for 66% of its total revenue. And the business scope of its travel agency is 100 times of that of CYTS, which ranks the first among the listed Chinese travel agencies. CYTS’s annual revenue in 1999 was 8.4 billion Yuan. World-renowned hotels are highly concentrated. Of the top 10 hotel groups, there are nine based in the United States. Such a high degree of concentration means a strong competitive edge (O’Neill & Mattila 2006, p.152).

Annexing small tourism groups by means of merger contributes to its rapid expansion. In today’s world, it becomes a trend for the enterprises in different countries to conduct mergers and acquisitions in order to strengthen their competitiveness, and the tourism industry is no exception (Gee 1994, p.117). In the middle and later periods of the 90s, American Express accelerated the pace of expansion and purchased all the shares of Havas Voyages which had the largest sales network in France. For the hotel industry in the United States, 1997 was a year of mergers and acquisitions, during which the number of mergers and acquisitions doubled as compared with that of the previous years. Such frequent mergers and acquisitions would inevitably re-divide the world hotel market (Gee 1994, p.118).

The organizational structures of international tourism groups began to be virtualized. The world economy is in a transitional period, changing from the industrial economy to the knowledge economy. The enterprises all over the world are experiencing three major knowledge-based changes; for instance, increased collaboration, decentralized management and decentralization and intelligent infrastructure building (Gee 1994, p.118). Under such circumstances, the tourism groups’ operation is moving towards virtualization, and even capital intensive hotel industry is no exception. In 1997, many hotel groups in the developed countries established strategic alliances with their competitors (Dussauge & Garrette 1995, p.521; Jarillo 1988, p.33; Harrigan 1987, p.67; Gomes-Casseres 1996, p.127).

The management status of tourism group in China

International tourism groups have entered the mature stage of development. Chinese tourism groups should learn from their management experience; in terms of management thoughts, products should reflect the market demand, sales should have a clear market positioning, and the businesses should rely on a thought-out marketing plan. In terms of the management system, property rights should be separated from management rights; a budget control should be adopted in finance; the theory of “only one master” is implemented in administration; a “line” principle is pursued in management to avoid overlapping management; in daily operations, a system of rules and regulations should be established and working procedures and assignment of responsibilities should be explicitly stipulated in documents (Eyster 1997, p.21; Eyster 1993, p.16).

More emphasis should be made on human resources; for instance, the large tour groups in the United States pay more and more attention to the attitudes of their employees. It has become one of the popular human resource management approaches for them to carry out a survey on the attitudes of their employees (Nebel 1991, p.118; Bond & Galinsky 1998, p.122). With the transnational expansion of the groups of the developed countries, more importance has been attached to the human resource management in cross-cultural operations (Roper & Brookes 1997, p.147; Amstrong & Connie 1997, p.181). In terms of the ability to run large companies, guided by the advanced management theories, enterprises in the developed countries far outweighed the Chinese ones in both capacity and level of management (Prahalad & Hamel 1990, p.21; Savage 1996, p.122; Pizam & Connie 1997, p.127).

The impact on the international market

Through a scientific method of operation, tourism groups monopolize the tourist market. Meanwhile, through online booking, tourists’ flow will be effectively controlled. Take American Express, for example, it has annexed many small tourism groups through mergers, therefore its businesses develop very fast; and its slogan is “With American Express, life is easier wherever you go”. Another example is the US Rosen Group. Its affiliated outlets are scattered all around the world. They act in cooperation with each other across a great distance, forming a large network. The emergence of international hotel chains greatly changes the tourism market. (Eyster 1993, p.16)

The impact on Chinese tourism market

Before China’s entry to the WTO, large international tourism groups did not have much impact on the businesses of the Chinese travel agencies. Therefore, the Chinese government did not pose many limitations on foreign-funded travel agencies operating in China. As China joined the WTO, its tourism market was opened to the outside world and a lot of foreign investment has officially entered the Chinese tourism market. To date, there have been 5 joint venture travel agencies in China. But China’s hotel market opened to the outside world earlier, a great number of international hotel groups have made their way into the Chinese market, which has a strong impact on Chinese hotel markers. The relevant situation is as follows: large international groups are very optimistic about China’s tourism market. With the edge in-network and group, they constantly plan to seize the Chinese market. Bass, Hyatt and Marriott and other ten well known international hotel groups have set up altogether 574 hotels in China. Marriott Hotels has already established 57 hotels in China now and plans to increase that number to 100 in the next five to six years (Feng 2001, p.86).

The outlets of international hotel groups in China concentrate on big cities and tourist cities. Hyatt Hotels Corporation entered China in 1986 and now runs hotels in Tianjin, Shanghai, and Xi’an. Shangri-La in China opened 36 hotels (Nash 1996, p.34). They are located in Beijing, Xi’an, Beihai, Shenyang, Changchun, Qingdao, Dalian, Shanghai, Harbin, Wuhan, Xiamen, and Shenzhen and another 10 will open a business in Lhasa, Yangzhou, Qinhuangdao and other tourist cities between 2012 and 2013. International hotel groups have expanded from the upmarket to the middle range market in China. Operators of the foreign-funded hotels find that exploring the middle range market can not only bring a faster return on investment but also can help them remain competitive in the Chinese market (Li 1998, p.12). Days Inn Hotel whose businesses mainly cover the middle and low rated hotels built 10 new hotels in China in 1998 and also plans to build 22 more in a bid to become the largest international hotel group in the Chinese market.

With China’s accession to WTO and the complete opening up of tourism to the world, the large international groups will have a bigger impact on the Chinese tourism industry. The General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS) is an important part of the WTO institutional framework. It explicitly stipulates the basic obligations that the member states have to fulfil as well as the general principles that they have to follow. Implementation of these provisions will enable the Chinese market to be global and will bring great challenges to China’s tourism industry (Li & Lin 2000, p.13).

The development status of tourism groups in China

China’s tourism groups have made some achievements but they also face many problems and conflicts (Liu 1999, p.41).

Macro-institutional environment

The institutional environment for the Chinese tourism groups is changing from a planned economy to a market economy and it is in a transitional period, which poses great challenges to the development of the tourism groups in China. These challenges are mainly reflected in:

- The non-liquidity of property rights limits the growth of the tourism group; under the current ownership, property rights are in some way fixed in a certain government department (Liu1999, p.41).

- The underdeveloped capital market; at present, China’s stock market and bond market are far from perfect. There are various restrictions in bank loans and venture capital development is still in its infancy stage. All of this has greatly hampered the large scale development of the large groups.

- The government-appointed bureaucracy hindered the establishment of the modern enterprise system.

- Non-commercial purposes limit the groups’ development.

- Serious local protectionism

- The failure of the government macro-control on hotels

- The de facto absence of the owners of state-owned assets. At present, although it is clear that state-owned assets administration bureau at all levels can represent the state to exercise the power of managing the state-owned assets, they do not assume responsibility for profits and losses of the assets, and neither do they have the rights to recover the profits from the state assets management. And this has lead to the great loss of the state-owned assets in various ways (Liu 1999, p.42).

The development defects of tourism enterprises

Affected by various factors, the development of Chinese tourism enterprises are not healthy, and they cannot compete with the enterprises of the developed countries. As players in line with market competition, enterprises are pursuing the unity of economic and social value. However, under the inertia of China’s planned economy, China’s economic development of tourism enterprises is not satisfactory, leading to a lack of competitiveness in the whole industry in China. Meanwhile, the international consortium with international funds entrained into China resulting in a fiercer competition (Yang & Zhang 1999, p.24). In front of the major international tourism company’s attack, the living space of those single tourism enterprises is getting smaller and smaller with the danger of being annexed (Wang 2000, p.22).

Most of China’s tourism groups have not grown to the mature market players, thus, they cannot use the internal mechanism of the enterprise to achieve economies of scale. First of all, the ultimate beneficiaries of state-owned and collective tourism enterprises are not the enterprises themselves, thus the state-owned tourism enterprises are not true market players. Secondly, those groups are formed by administrative order, where the power of human, financial, and material has no change, thus, there are no clear organizational structures in the enterprise (Yang & Zhang 1999, p.25).

Compared to tourism groups in other developed countries, China’s tourism group management is still immature. First, many tourism groups are integrated by contract, so the collaboration is not firm. Because it is not based on property rights, it lacks control over the core business, member companies act according to their comparative advantage, and the group has no centralized leadership as they are structured loosely, thus its overall advantage cannot be played well (Angwin 2007, p.37). Secondly, there is no suited business strategy and no talents with strategic thought. Thirdly, they are short of mature group management and operational capacity of human capital. Fourthly, there is a lack of strong marketing power and network. Finally, there is a lack of well-known brands (Ruan 2000, p.53).

Obstacles to the conglomeration of Chinese tourism enterprises

Property rights

The barrier of property rights refers to various barriers existing during the property transaction between different owners in the process of tourism enterprises conglomeration (Keenan & White, 1982, p.37). Property barriers exist mainly in the reflection of the murky position of owners, inappropriate system, which result to other problems such as poor distribution channels between tourism enterprises and private enterprises (Ruan 2000, p.57).

The first concern is the transformation and reconstruction of tourism enterprises. In a broader perspective, it is an inevitable trend for state-owned assets to retreat from the highly competitive tourism industry; however, proceeding from a realistic operating environment is a serious issue troubling the Chinese state-owned tourism enterprises and management activities such as rent-seeking behaviour of various stakeholders restricted its market-oriented process to a considerable extent; insufficient theoretical support for institutional transformation and organizational change also impeded property rights trading system formation amid China’s tourism development (Keenan & White 1982, p.37).

Secondly, a great deal of severely fragmented state-owned assets in the field of tourism cannot form cross-regional, cross-industry or cross-ownership tourism enterprises groups. With the acceleration of the process of hierarchical management of state assets, this kind of situation could get worse; for example, a number of local governments and some super-sized state-owned enterprises ignore the nature of tourism and its inner connection, making Beijing Tourism Group solely the possession of Shanghai, Jinjiang International Group of Tianjin, Shanxi Tourism Groups of Shanxi, GDH Guangdong Hotel Management Holdings Limited of Guangzhou, etc. If property barriers like these cannot be solved effectively, it will be impossible for the Chinese tourism industry to realize its cross-regional conglomeration through opening option (Hammer & Champy 1993, p.91).

Capital structure

If one industry cannot form an effective fusion mechanism of industrial capital and financial capital, then this industry is hopeless. The current problem is that on one hand, China needs capital consolidation in the tourism industry and on the other hand, the current tourism industry’s background operations, and profit model seem to be too murky for the capital market to invest in. The poor performance of some of the already listed tourism enterprises discouraged the capital market involvement to a certain extent. It is believed that there is a high degree of information asymmetry between the current capital markets and tourism product market (Ruan 2000, p.57).

The tourism sector in Shenzhen and Shanghai stock market consisted of a total number of 28 tourism based companies (including the B shares), among which there are hotels and restaurants as follows: Huatian Hotel, Century Plaza Hotel, Dongfang Hotel, Huandao Industry, International Building, China World Trade Center, Dalian Bohai, Jinde development, Beijing Capital Tourism, New Jinjiang, Shares of New Asia, Tibet Pearl, Baohua Industry, Lawton, Holy Land and The Chinese Pan Tibet tour. According to the statistics of the business operation of listed hotels in 2001, lack of growth momentum is a major concern.

Most business indicators fail to reach the overall level of the vast majority of listed companies. From the growth indicators, the average revenue growth of 2001 was only 5.9%, and 13.6% in 2000, far below the growth rate of nearly 20% contributed by the listed tourism enterprises. It is noteworthy that the overall profitability of hotel companies suffered from a significant decline; earnings per share are registered as less than 1 cent for hotels in 2001, the average return on net assets was only 0.35%, and the average net profit was only 195 million Yuan. If tourism enterprises with these performances do not attempt to intensify their capitalization and strengthen competitiveness through assets re-organization, then these tourism enterprise groups will no longer be attractive to other companies (Prahalad & Hamel 1990, p.24; Ruan 2000, p.57).

Strategic management and internal management

Those barriers mentioned above are mainly from the macro level, so is that to say China’s tourism enterprise groups can successfully register progress when environmental factors are available? Not necessarily. In a sense, the problems arising from the internal world of the tourism industry and enterprise may pose far more serious threats to the development of the industry. The first barrier is about human resource. Three problems are raised: Enhancement of Chinese local and professional managers’ abilities and social recognition; follow-up training and retaining personnel; and combination of specialized teams. Now from the aggregate point of view, employees exceeded more than 100 million people merely in star-rated hotels. Over the last 20 years, a considerable number of professionals and managerial talents emerged; here the so-called human resource barrier is in terms of the services quality instead of structure. In this regard, we must establish the concept of corporate human resources.

In the first Chinese professional hotel managers seminar, the former chairman of Lausanne Hotel School, Ms Jiddah cited an example to illustrate the role that hotel management expertise plays in other industrial and commercial business; alumni of hers in Shanghai had left the hotel industry and then served at a German building materials company, but still as the head of Shanghai Alumni Association (Prahalad & Hamel 1990, p.24; Ruan 2000, p.57). He believed that 97% of the knowledge he could use came from Lausanne, such as the service chain system, operating system, human resource management. While clearly recognizing self-worth, we also need to learn from other industries and put the expertise to use in the field of hotel management (Hammer & Champy 1993, p.91).

The second hitch is the technical barrier, including hard information technology and soft management system. With the expansion of the scale and layout of the company, large enterprises still cannot manage the necessary information technology and management system. Now some of the hotel groups have no real sense of their strategic research and development centre, leading to the fact that there is no effective technical support for the group’s investment strategy, market strategy, product innovation and human resources sustainability, etc. (Hammer & Champy 1993, p.91).

The management mode with management philosophy, management system and operating mechanism as the core serves as the basic guarantee for the effective operation of tourism enterprise groups. For those mature management companies, their success is not a result of the people, but of the system. The vice president of the development department of InterContinental Hotels Group China, Mr Huang Deli, once introduced that the group’s customer satisfaction surveys are made by an independent agency, so whether you are domestic or foreign management personnel, it’s very necessary to make every employee work hard on every single service so as to make the tourists, the owners and the groups satisfied. For Chinese tourism enterprise groups, especially those who are more dependent on the output of the management mode, making great efforts to study business management system and enforcement mechanisms will be very necessary. The fundamental reason is that we rely on people instead of the mechanism to ensure good performances, in other words, our management mode is unduplicated (Hammer & Champy 1993, p.91).

The third barrier concerns the localization of cross border tourism enterprise groups. The strategy for the localization of cross border tourism enterprise groups could push the development of Chinese tourism enterprise groups and also an inevitable choice considering its main purposes. For cross border tourism enterprise groups, localization provides a win-win platform; business costs are lowered while reward costs for management are raised. So what is localization? In reality, it is the localization of human resource. In fact, this is just the surface of things, only by proceeding from the ideas of the Chinese culture and conducting innovation with the relevant investment strategy can we realize the localization of cross border tourism enterprise groups. In this regard, the Intercontinental Group currently listed in the London Stock Exchange has done an impressive job. But not every cross border tourism enterprise group entering China is endeavouring to carry out the localization strategy. If there are still obstacles on the ideas and actions for cross border tourism enterprise groups, then Chinese tourism enterprise groups will lose the most precious opportunity to learn and cooperate with them, thus slowing down the pace of development (Ruan 2000, p.59).

Tourism Group’s market development

China Tourism Group’s development only has a history of twenty years. Some groups have made success, but overall, the growth of China’s tourism group is not optimistic. The success lies in the fact that after 20 years of growth, some companies have been the world leader standing in the top 300 in the list. In 2009, China’s Shanghai Jinjiang Group managed 707 hotels and business offices, 107,000 hotel rooms, ranking 13th on the global hotel list. Home Inn managed 616 hotels and 71671 hotel rooms, ranking 19th on the list, Shangri-la ranked 35th (Dussauge & Garrette 1995, p.512). While the deficiencies lie in, those travel groups stay at a lower level and contribute little to the integration of the domestic hotel industry (Zhang 1999, p.24). Compared with the total number of 14,000 star hotels, only 30% of the hotels providing foreign services achieved group management (Gao 2001, p.26).

New trends in the development of the tourism group

Recently, the development of China Tourism Group is accelerating, the conglomeration of tourism industry appeared in a variety of forms. The forms included:

- A Loose strategic alliance

- Tourism enterprises are founded in different provinces focusing on the local tourist attractions. Anhui, Jiangsu, Guangdong took the lead to establish the local tourism enterprises. The basic model is that through asset allocation, the former subordinate enterprises under the local Tourism Bureau are transformed into travel groups directly. Those travel groups are playing locally, with operations of hotels, travel agencies, restaurants, taxies, tourism attractions and department stores (Zou 2000, p.124). For example, Beijing Tourism Group Co., Ltd. was established in 1998 and was renamed in September 2000 as Beijing Capital Tourism Group Co. Ltd. (referred to as BTG). It is a large conglomerate approved by Beijing Municipal People’s Government, owning the authorization of establishment and the management of state-owned assets.

- Recently, large players in different fields swarmed into the tourism market. After that, they all drew up plans on conglomeration, which attracted attention from all aspects. Huiming Gu (2000, p.202) thought that the current enterprises are focusing on capital operation; in the process of shifting from a planned economy to a market economy, companies can conglomerate through government’s help and market power (Gu 2000, p.202).

The developing strategy of the Chinese travel group

The macro-development strategy of the Chinese tourism group

On the motivation of the conglomeration of tourism enterprises, there are three different voices in the academic world:

Government-led strategy

The reasons to advocate for government-led strategy are based on three points: First, China’s tourism development experience over the past 30 years; second, the lessons learnt from the developed countries; and third, the nature of tourism industry makes it to revolve in many related sectors (Prahalad & Hamel 1990, p.24; Ruan 2000, p.57).

Government support for advanced project

Some scholars have argued that the government should actively encourage the consortia to enter the hotel industry or form groups, but the method should be based on acquisition, equity transferring and improving the existing hotels. In particular, the government should promote the cooperation between consortia and hotels and famous hotel management companies in order to let big financial groups hold shares and pass the management rights to the management company; thus, setting up the giants in hotel industry (Zou 1999, p.122).

The market-oriented strategy

Experts in the industry thought that capital is the key to the success of Chinese tourism conglomeration. That means that capital management should be a mode of operation to form tourism groups. In order to develop tourism groups according to the market-oriented standards, the expansion ought to follow the market laws. First, conglomerate groups should implement an internal management strategy to improve management and enhance the effectiveness of the internal allocation of resources. By expanding markets, companies can develop new products, adjust the organizational structure, improve management, increase productivity and control costs to integrate the internal resources under the capital structure (Wang 2006, p.202).

Business strategy of Chinese Travel Group

Conglomerating a group itself is not hard. What is difficult is what comes after the establishment of a group; can it develop orderly and durably? (Wang 2006, p.212).

China’s tourism market development strategy

- The strategy in the country: Major travel agencies should expand under the same brand and integrate the internal business. The market focus should be mid-end domestic tourism and business tourism market (Dai 1999, p.124). Low end starred hotel are the best choices for agencies to conglomerate and network (Zhang, Qin & Li 2000, p.43).

- The strategy worldwide: In the process of merging with the international tourism market, the main competitors are changing from the small and medium enterprises to large enterprises and enterprise groups, and the competition among countries bears a nature of global strategy (Guo 2000, p.201). The development of the international strategy will not only help to make extensive use of foreign resources but also improve the international competitiveness of China’s tourism enterprises (Li 2000, p.14).

- The market development space of Chinese tourism group: under the context of industrial restructuring in the country, a comprehensive restructuring of the asset structure has happened in some industries; thus, a number of new tourism enterprises with modern management system have come into being. These companies with loose alliances and the ones with systematic management are the ideal companies for cooperation with the Chinese tourism groups.

For example, a foreign trade group might own couples of luxury hotels, such as the World Trade Center under economic and trade department, Shangri-La under Minmetals Corporation, Fujian’s foreign trade hotel, Changchun International Trade, Shenyang Business Center. In the recent 10 years, those major trade companies conducted strategic adjustments to point at industrial fields. The New Asia Group in Shanghai is an original business enterprise without a link to industry. New Asia Group consists of hotel management companies, travel agencies, taxi companies, fast food chains, restaurants and other assets under its management. Shanghai’s New Asia Group is an integrated tourism group with great influence (Prahalad & Hamel 1990, p.24; Ruan 2000, p.57).

China’s tourism development strategy within the Group

Without cohesion, the effectiveness of conglomeration is not much strong; there will be no business combination, no powerful group benefits, no upwards power, and no sustainable development vitality (Wang 2006, p.210). Since the development of China’s tourism group determines the group’s internal cohesion, there are many studies that have been studied on this topic. The specific strategies can be divided as follows:

- The importance of clear property rights is the consensus within the business and academic fields: The facts and figures of the recent years show that the diversification of property rights, joint-stock reform and the list of the shares on stock can not only increase the funding for the tourism enterprises but can also dump the non-performing assets, select a high-quality asset for listing and raise more money (Zou 1999, p.120). As the groups have not solved the core issues like the form of restructuring their corporate assets and property rights allocation, they failed to form an organic combination and failed to form a strong large scale and intensive management, resulting in the high cost of doing business, bloated organization and low efficiency; thus, the result of conglomeration is not obvious and the awareness is not high (Zhang & Zhang 2000, p.163). The Chinese Travel Group should stand on the basis of the clarification of property rights, improvement of the level of capital operation, and transfer of the capital to cost-effective enterprises and fields so as to achieve capital efficiency (Prahalad & Hamel 1990, p.24; Ruan 2000, p.57).

- Improved management: First, companies ought to concentrate on the development of human resources; after the establishment of a travel group, more expert consultants, strategic management staff and professional managers are needed. Tourism human resources development is an important guarantee for the orderly and sustainable development of the group. Professional management is a necessary means to accumulate the core competitiveness for the travel group (Liu & Dong 2001, p.132).

Secondly, travel groups need to establish related organizational structures; organizational innovation of tourism enterprises has two means, one is to collaborate with organizations in the fields and the second is to corporate with large companies and co-invest in tourism enterprises (Dai 1999, p.127). Virtual chain entails a management model of using the strongest power and limited resources to maximize its effectiveness, based on computer network technology and it will be an indispensable operating mechanism in the future (Dong 1999, p.125). With the development of tourism, it is a realistic and feasible way to develop Chinese tourism by establishing a strategic alliance (He & Xu 2007, p.52).

- The innovation of mode of operation: In the process of development, tourism groups need to create an operation mode according to their environment and conditions. Actually, the operation mode is diversified (Wei 2000, p.130). The conglomeration needs to build five resource system, human resource, capital resource, material resource, time and space resource and information resource (Wei 2000, p.133). From the perspective of market operation of tourism enterprises, the competition of level 1 is price competition, which is on the lowest level and most common one. Level 2 is quality competition, and level 3 or the highest level is culture competition. (Wei 2000, p.133).

Research Methodology

Introduction

A methodology is a process of instructing the ways to do the research. It is, therefore, convenient for conducting the research and for analyzing the research questions (Bryman & Bell 2011, p.158). The process of methodology insists that much care should be given to the kinds and nature of procedures to be adhered to in accomplishing a given set of procedures or an objective. This section contains the research design, study population and the sampling techniques that will be used to collect data for the study. It also details the data analysis methods, ethical considerations, validity and reliability of data and the limitation of the study.

Research philosophy

For this part, choosing a philosophy of research design is the choice between the positivist and the social constructionist (Easterby, Thorp & Lowe 2008, p. 67). The positivist view shows that social worlds exist externally, and its properties are supposed to be measured objectively, rather than being inferred subjectively through feelings, intuition, or reflection. The basic beliefs for the positivist view are that the observer is independent, and science is free of value. The researchers should always concentrate on facts, look for causality and basic laws, reduce phenomenon to simplest elements, and form hypotheses and test them (Bryman & Bell 2011, p.160).

Preferred methods for positivism consist of making concepts operational and taking large samples. The view of the social constructionists is that reality is a one-sided phenomenon and can be constructed socially in order to gain a new significance to the people. The researchers should concentrate on meaning, look for an understanding of what really happened and develop ideas with regard to the data. Preferred methods for the social constructionists include using different approaches to establish different views of the phenomenon and small samples evaluated in-depth or over time (Saunders, Lewis & Thornhill 2009, p. 87). For the case of analyzing the relationship between employee commitment and job attitude on service quality, the philosophy of the social constructionists was used for carrying out the research. Because it tends to produce qualitative data, and the data are subjective since the gathering process would also be subjective due to the involvement of the researcher.

Sample selection

Population refers to the total elements that are under investigation from which the researcher draws a conclusion (Saunders, Lewis & Thornhill 2009, p. 90). A sample is a subset of the population, i.e. it is a representation of the total population (Saunders, Lewis & Thornhill 2009, p. 90). This study mainly used a non-probability design of sampling. In this design, not every participant in the study has an equal chance of being chosen. Non-probability sampling design does not utilize much cost and time, hence it is widely preferred. When smaller samples are used, a non-probability research design is susceptible to errors, thus, normally a larger sample size is selected (Bryman & Bell 2011, p.160). In addition, it was preferred for the number of observations to be more than the number of variables as a regression analysis was to be conducted.

Research design

In line with the main objective of this study which is to explore the development and management of Chinese tourism enterprises conglomerating, this study employed a cross-sectional research design. Under this design, 110 respondents were targeted. They were issued with questionnaires to assist with data collection. The respondents were assured of the confidentiality of their participation.

Statistical method

Descriptive statistics and inferential statistics were both applied in the study in order to test the hypotheses.

Descriptive statics

Descriptive statistics is mostly applicable for analyzing numerical data. It uses distribution frequencies, distribution of variables and measures of central tendencies (Saunders, Lewis & Thornhill 2009, p. 93). The characteristics of the sample chosen will be used to compute frequencies and percentages with regard to the questionnaires.

Inferential statics

Inferential statistics gives the researcher the chance to convert the data into a statistical format so that important patterns or trends are captured and analyzed accordingly (Easterby, Thorp & Lowe 2008, p. 72). Regression analysis is utilized in inferential statistics. Regression analysis is employed to check on the relationship between a dependent variable and an independent variable. It allows the researcher to predict and forecast the expected changes to a dependent variable when one independent variable changes (Easterby, Thorp & Lowe 2008, p. 72).

Data Collection and Instrumentation

Questionnaires were used to collect the data. The questionnaires were issued to 110 respondents who were mainly employees in the Chinese tourism industry. The participants’ responses were treated with much confidentiality.

Data Analysis Methods

Data from the survey were entered into the Excel spreadsheet program for future analysis. Data were analyzed using SPSS and statistical tools.

Limitation of data collection methods

There have been a lot of concerns on additional budgetary expenses for collection of the data, regardless of whether the gathered data is really genuine or not and whether there may be an explicit conclusion when interpreting and analyzing the data. In addition, some employees were reluctant to offer some information they deemed confidential and unsafe in the hands of their competitors. This posed a great challenge to the research as the researcher had to take a longer time to find employees who were willing to give out adequate information.

Validity and reliability

The validity of the data represents the data integrity and it connotes that the data is accurate and much consistent. Validity has been explained as a descriptive evaluation of the association between actions and interpretations and empirical evidence deduced from the data. More precaution was taken especially when a comparison was made between employee commitment and job attitude. Employee motivation may differ from business to business and may not be identical in an industry. Reliability of the data is the outcome of a series of actions which commences with the proper explanation of the issues to be resolved. This may push on to a clear recognition of the yardsticks concerned. It contains the target samples to be chosen, the proper sampling strategy and the sampling methods to be employed.

Findings, Data Analysis and Interpretation

Introduction

This section covers the analysis of the data, presentation and interpretation. The results were analyzed using SPSS and statistical methods like Pearson correlation matrix.

Summary of descriptive statistics