Introduction

Coal mining is one of the major mining industries in the United States that generates income for a big portion of the population. The majority of the states are now engaged in coal mining activity (35 of the 50 states). When not strictly regulated, coal mining can cause injuries and sicknesses to miners due to coal gas emissions. Burning coal emits substances considered pollutants, such as sulfur dioxide (SO2), nitrogen oxides (NOx), and particulate matter (PM) which are harmful to the environment. On the other hand, sicknesses acquired by coal miners in those early days of mining were diseases such as coal workers’ pneumoconiosis, silicosis, and black lung, among others.

Controversies occurred between the government and miners and operators who were not yet properly regulated or supervised during those times. Countless issues on safety and regulation rocked past discussions about laws and on the inability of the government to help the miners and the industry as a whole.

As more and more accidents happened, and more miners succumbed to disease and disability due to coal gas inhalation, laws were enacted by Congress to regulate the industry and help the miners. There have been many such laws, and myriads of agencies created in the process, making significant developments in the regulation and control of the industry.

A question may be asked, can this give us the impression that coal mining is not anymore a threat to human lives and the environment?

There’s much to be done, and laws are not laws if they are not effectively implemented. People and government should continue to devise means for the improvement of society and the world, more specifically the environment which has been continuously abused. Global warming and climate changes are a threat to humanity and our dear Mother Earth. The subject of coal mining, clean coal, and a clean environment is a serious topic for discussion.

Here’s an example of a human drama that occurred in a not-so-distant past:

On a fateful summer of 2002, a game of death was played – one in the Sago Mine involving 13 West Virginia miners and the other in Pennsylvania’s Quecreek Mine. The Quecreek miners dug through the wall of a tunnel which unleashed millions of gallons of water. Nine of them narrowly escaped death and were later rescued. Twelve miners lost their lives at Sago when an explosion generated carbon monoxide. They had no way how to get away with carbon monoxide. (CNN, 2006).

Coal mining continues to be a source of income for an ordinary American miner. Generally, it will continue to be a part of the U.S. economy. It provides man and technology in particular, with the necessary tools for production. What is necessary is for it to be safe for the workers and the environment. Modern technology, effective means of communication, laws, programs, and agencies of the government have helped improve working conditions and the environment. And they have to be revised as time goes by.

Moreover, there have been some significant developments in the regulations and control of government agencies that a report by James Weeks (2006) is relevant to state here:

Before the passage of the 1969 Coal Mine act, the fatality rate of U. S. miners was approximately 0.25 fatalities per 100 workers per year, four times that of miners in Western European coal-mining countries. For the first 10 years after the act, it declined each year to a level approximately the same as that in European mines. Since then, it has declined further, so that now, coal mines in the United States are among the safest in the world at an annual fatality rate of approximately 0.03 fatalities per 100 workers. Even so, the fatality rate in mining remains the highest of any major industrial group in the United States. (Weeks 2006, p. 41).

While this is a positive outlook on the present and the future of coal mining in the United States, there are so many things to be done, with so many challenges ahead.

The U.S. Department of Energy has programs to address these issues, one of which is the Clean Coal Technology Program, a “series of facilities built across the country [which] are carried out on a commercial scale to prove technical feasibility and provide the information required for future commercial applications” (Department of Energy, 2001). The program aims to reduce the emissions of pollutants SO2, NOx, and PM, through strict environmental standards.

History of coal mining in the United States

The earliest recorded history of coal mining is the discovery of coal by the Indians in Arizona in 1000 A.D. when they used coal to bake pottery. Then in 1701, the Huguenot settlers found a coal mine on the James River, in Richmond, Virginia. But it was in 1830 when locomotives were manufactured which used coal as fuel. Fast forward, there was then increased demand for coal when from 1973 to 1974 the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Companies (OPEC) started the infamous oil embargo. And then some few years ago, a law was enacted – the Energy Policy Act of 2005 – which allows the use of coal through clean coal technologies. (American Coal Foundation, 2005).

This, in a nutshell, is a brief history of coal mining, although the whole story cannot be covered in this paper. It is safe to say, however, that coal mining in the United States has reached a stage where there are many innovations, perhaps due to laws and statutes enacted that have been polished or revised through the years to make coal mining safe and truly beneficial to the ordinary American miner and the environment.

Coal mining has spread all throughout many states because of the vast uses of coal to production. As a fuel source for power generation, coal will continue to be a driving force for the U.S. economy. The rest of the world still depends on coal as a source of electricity. Coal “has remained the principal fuel for the generation of electricity and is likely to continue to do so despite losing ground to other fuels” (International Labour Office, 1994, p. 5). Above all, coal is cheap.

The significance of coal in the U.S. economy can not be undermined. Coal is a commodity used to process other commodities. It is used to produce a substance known as “coke” which is likewise essential for the production of iron and steel. (American Coal Foundation: Glossary, 2007).

Electric companies use coal, and large industrial and manufacturing companies also need coal in their production.

McElfish, Beier, & Environmental Institute (1990) state:

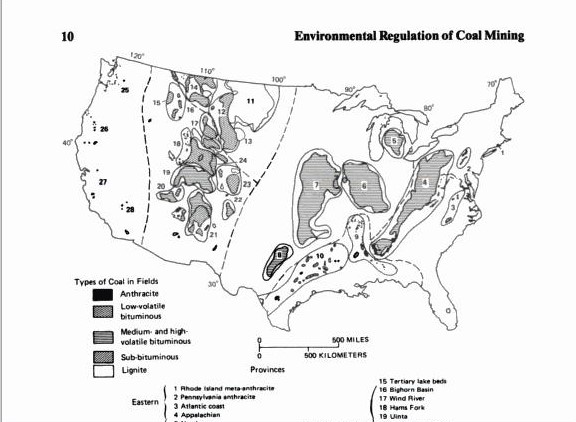

The United States has demonstrated coal reserves of approximately 480 billion tons, about 35 percent of the world’s reserves. Coal is found in 35 of the 50 states and is actively mined in 26 states. [C]oal reserves are estimated to be sufficient to meet current rates of domestic consumption for 200-300 years, depending on recovery rates. (9)

How coal was extracted in the early days

Hayes (2000) describes the shafts and drifts of early coal mining:

At first, coal was worked where it was visible at the surface or just below thin deposits of soil. When simple digging became impossible, shallow shafts were sunk and the coal was extracted around the bottom of the hole. These were known as ‘bell pits’[…] When collapse was imminent, another shaft was sunk nearby. Early mine shafts or pits were variously shaped: round, oval, rectangular, and square. (p. 5)

Of late, this has been modified by new miners with the emergence of new tools and technology in mining.

Example of industries that use coal

Major industries use coal in their productions. At present, the major users of coal in the United States are, among others:

- Pacific Gas and Electric – “incorporated in California in 1905, is one of the largest combination natural gas and electric utilities in the United States [and] based in San Francisco” (PG&E, 2009).

- Union Pacific Railroad – is “the first transcontinental railroad; the greatest, most daring engineering effort the country had yet seen. The time was the 1860s” (Union Pacific, n.d.).

- Steel corporations such as the ArcelorMittal Steel, a merging of Mittal Steel and Arcelor “to create the world’s first 100 million tonnes plus steel producer” (ArcelorMittal 2007).

With much of the earth’s coal mines already been tapped by different countries, how much of it still remains for man?

“The world’s coal reserves were estimated in 1992 to be 1,039 billion tonnes, almost equally divided between hard coal and lignite. This makes coal the most plentiful of fossil fuels, with reserves amounting to about 170 years of hard-coal consumption at current levels and about 400 years’ consumption of lignite.” (International Labour Office, 1994, p. 8) This was in 1992 and there could be present developments and statistics.

The impact of coal mining on man and his environment is varied; there are advantages and disadvantages. In the United States, discussions and controversies have slowed down due to the attention focused by the government in addressing the issue. The Clean Coal Technology Program has been introduced in 1985 “to minimize the economic and environmental barriers that limit the full utilization of coal” (Department of Energy, 2001, p. 1).

Positive impact of the regulation

Laws have been enacted by Congress, and federal and state agencies were subsequently created to address mining issues and concerns. Miners’ complaints on benefits due to injuries and occupational sickness have also been addressed. More importantly, the workplace is conducive to a wholesome work environment because of the laws and the agencies created. These are among the positive impact of the regulation.

As mentioned earlier, there are countless federal and state agencies regulating coal mining across states. These agencies have different roles and policies to safeguard the lives of miners, including their health and safety, and the environment. They also have different environmental policies and the scope varies from state to state.

Discussions on global warming and climate change have superseded mining issues according to McElfish, Beier, and Environmental Law Institute (1990, p. 1). Concerns are more on acid rain, toxic waste, tropical deforestation, and safe drinking water. Laws have generally resolved mining issues. The remaining issues can be taken care of by the federal and state agencies.

The Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act

The Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act of 1977 came to the fore as a result of the incidents and accidents that had occurred in mining areas across the United States. There was the inability of the authorities to address miners’ complaints regarding benefits as a result of occupational sicknesses, and other pressing issues in the workplace. The main objective and philosophy are this contained in the following opening paragraph of the Act:

“[M]any surface mining operations result in disturbances of surface areas that burden and adversely affect commerce and the public welfare by destroying or diminishing the utility of land for commercial, industrial, residential, recreational, agricultural, and forestry purposes, by causing erosion and landslides, by contributing to floods, by polluting the water, by destroying fish and wildlife habitats, by impairing natural beauty, by damaging the property of citizens, by creating hazards dangerous to life and property by degrading the quality of life in local communities, and by counteracting governmental programs and efforts to conserve soil, water, and other natural resources” (SMCRA §101(c), 30 U.S.C. §1201(c), ELR STAT. SMCRA 003, cited in McElfish et. al., 1990, p. 2).

This is a preamble – sort of – because it contains the objectives and the circumstances surrounding the enacting of the law. There was a great controversy during its enactment. It was twice vetoed by President Ford; then-President Carter signed it into law on August 3, 1977. It was further challenged in courts but was upheld by the Supreme Court in 1981. (McElfish et. al., p. 5)

SMCRA has “beneficial impacts upon coal mining in the United States” (p. 1) and has resolved a lot of mining issues. The issues include:

- “The eradication of so-called ‘wildcat’ operations – those mines which had no permits that performed no reclamation whatever.

- “The removal of the ‘shoot-and-shove method of surface coal mining, whereby a coal seam was dynamited and the overburden pushed over the slope” (p. 1).

The SMCRA also resolved issues such as the quality of the permitting process. The permit is required to protect public health, safety, and the environment. It “requires the mine operator to plan the operation in detail to identify and avoid adverse environmental impacts and to facilitate site reclamation, [and] gives the regulatory authority significant enforcement powers over the mining operation” (McElfish et. al., p. 53).

The law provides for the protection and enhancement of water quality, the surface effects of increased underground mining, the use of “unsuitability” designations as an integral part of the program, and the inadequacy of the abandoned mine land fund to deal with all past problems. (Pp. 1-2)

SMCRA also addressed the following critical issues:

- “The protection and enhancement of water quality,

- “The surface effects of increased underground mining,

- “The use of “unsuitability” designations as an integral part of the program, and

- “The inadequacy of the abandoned mine land fund to deal with all past problems” (McElfish et. al., 1990, p. 2).

In issuing permits, the SMCRA seriously takes into consideration, the surface effects and outcome because of underground mining. If this is not properly supervised, underground mining can result in the degradation of the surface land surrounding the mine. And there is also the problem that emanates as an outcome of an abandoned mine.

“The regulatory issues today include the prevention of hydrologic damage, the control of subsidence and subsidence damage, the establishment of adequate reclamation bond amounts, the use of permit-based enforcement, and the improvement of federal oversight” (McElfish et. al., p. 3).

Subsidence occurs as a result of an underground mine; it is necessary that an agency of the government should monitor and control the conduct of underground mining. Subsidence and subsequent ground degradation can be minimized with constant monitoring or supervision on the part of the federal and state agencies.

Karmis (2001) states:

“The twentieth century marked an era of great progress in mine health and safety. According to the National Safety Council’s statistics of selected industries, mining now rates near the top of the safer industries. Engineering and technical developments have contributed a great deal to the improvements in mining health and safety.” (p. xix)

Before, miners were not really seriously concerned about their health and safety. It is said that the injuries and diseases acquired from coal mining were acquired by miners because of their own lack of safety measures, aggravated by their behavior, a culture they have had. Now, there is a change in the human behavior of the miners in the workplace, a great improvement.

It is also required by law for miners to have regular training. They have to have this sense of safety in the workplace which can be attained through constant practice and training. An attitude develops through practice and training.

ILO statistics reveal that “120 million occupational injuries and 210,000 fatal injuries occur annually at workplaces worldwide [and] the mining industry has a high incidence of injury among all industry divisions” (Ghosh, Bhattacherjee, & Chau, 2004, p. 470).

H. L. Boling, in Safety in the Next Millenium (cited in Karmis, 2001), says:

“The road map to success will include a process that ensures safe production is continuous, consistent, and uncompromising. It will take integrating management’s involvement into an unwavering commitment to people and the safe production process; then, consistently following it up with action and example” (p. xix).

Boling points out that the miners and employees should be the primary concern in the introduction of measures and regulations in the workplace. These measures should never be compromised, must be continuous and consistent. It depends therefore on the agencies and people taking charge of the supervision and enforcement of laws that safety can be attained in the mining areas.

Bolling introduces the five principles of safety:

- “All accidents are preventable.

- “All levels of management are responsible for safety.

- “All employees have the responsibility to themselves, their coworkers, and their family to work safely.

- “To eliminate accidents, management must ensure that all employees are properly trained on how to perform every task safely and efficiently.

- “Every employee must be involved in every area of the safety and production process” (p. xix).

Where before there have been so many accidents and injuries in coal mining, now these have been lessened because of government regulations and monitoring, continuous and consistent intervention, and supervision by concerned agencies, individuals, and groups.

However, there are still some ill effects of coal mining that SMCRA has not totally eliminated. This is because there are still coal sites that do not comply with the regulations. Strict enforcement of laws is necessary at all times.

Worldwide, the talk is still on environmental concerns. The International Labour Organization reports of the environmental concerns “as far as emissions of acid gases during coal combustion were concerned” (International Labour Organization, p. 5).

Coal combustion produces pollutants and diseases to the miners that can only be countered through extreme care and safety measures by the miners, and strict enforcement of laws by government agencies. The agencies created by acts of congress have monitored and regulated coal mining to help prevent injuries and sicknesses such as lung disease, bronchitis, pneumoconiosis, among others.

MSHA and OSHA

On the question of regulators, Savit & Abrams (2001) state that “there are myriad federal, state, and local agencies that can affect health and safety at mining operations” (p. 115). These are the agencies mandated to enforce the laws and safeguard the lives of miners. They have intervening power and authority to ensure safety in mining areas.

Three federal laws have control and regulation on toxic substances in the United States, and these are:

- “the Mine Safety and Health act of 1969 (MSHA),

- “the Occupational Safety and Health Act (OSHA) of 1970, and

- “the Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA) of 1976” (Ashford and Caldart 2006, p. 39).

First of all, there are approximately 200,000 miners in the United States who work underground to look for coal and other metal and nonmetal commodities, and who are in danger of “fatal and nonfatal traumatic injuries, occupational lung disease (coal workers’ pneumoconiosis, silicosis, and lung cancer), and noise-induced hearing loss.” (Weeks 2006, p. 40)

The following is a list of agencies that play a role in a major accident and the regulation of the mine’s operations:

- Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA)

- Federal Railroad Administration (FRA)

- Environmental Protection Agency (EPA

- National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH)

- National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB)

- Chemical Safety and Hazard Investigation Board (CSB)

- U.S. Coast Guard

- Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms (ATF), (Savit & Abrams, 2001, p. 115)

MSHA

The Mine and Safety and Health Administration (MSHA) is an agency under the U.S. Department of Labor in charge of mine regulations. Congress enacted the Federal Coal Mine Health and Safety Act of 1969 as an offshoot of the miners’ strike in West Virginia for compensation for black lung and an accident that caused 78 deaths.

The act created the NIOSH “to perform epidemiologic research [and] the federal black lung program to compensate miners totally disabled by pneumoconiosis” (Weeks, 2006, p. 40).

NIOSH issues “criteria documents, reports, and comments, and conducting research on such ‘materials’ and ‘agents’ as coal dust, silica, and diesel particulate matter, as well as on health issues such as noise and ergonomics” (Savit & Abrams 2001, p. 120).

Another mandate of NIOSH is “to coordinate the activities of the Mine Safety and Health Research Advisory Committee (MSHRAC). The committee was formed in 1984 and has been active in advising MSHA and NIOSH on various mining-related health issues and potential research areas” (Savit & Abrams, p. 120).

OSHA

“The OSHA was created pursuant to the Occupational Safety and Health Act of 1970 and is a separate agency within the U.S. Department of Labor. [It] gives authority to the Secretary of Labor to promulgate standards for regulating health and safety in the workplace” (Savit & Abrams, 2001, p. 116).

On the other hand, the 1969 Act was amended in 1977 to create the MSHA which is similar to the OSHA structure. The act “requires miners to receive 40 hours of training in safety and health when first hired and 8 hours annually thereafter” (Weeks 2006, p. 40).

The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health is a federal agency that is a part of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) within the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). (Savit & Abrams, 2001, p. 120)

This agency is “responsible for research and prevention of workplace hazards” (Savit & Abrams, p. 120).

Differences between OSHA and MSHA

Both are agencies that have regulating power over coal mining sites and other industries which need to be regulated because of the hazards and other substances that might cause illness to workers when inhaled.

The OSH Act has jurisdiction over all 50 states, but Savit and Abrams (2001, p. 116) state that ‘operators of mines, as that term is defined in the Mine Act, are exempt under Section 4 (b)(1) of the OSH Act because MSHA has primary jurisdiction. As mentioned, the OSHA is a separate agency within the Department of Labor, which regulates mining workplace and exercises authority to promulgate and enforce standards over such facilities” (Savit & Abrams, 2001, p. 116).

There are differences between MSHA and OSHA with respect to enforcement capabilities. Under MSHA “underground mines must be inspected four times and surface mines must be inspected twice each year”; under OSHA, “inspections are discretionary” (Weeks, 2006, p. 41).

MSHA has broader jurisdiction which is that it covers all mines while OSHA does not cover employers with “10 or fewer employees” (Weeks, p. 41).

Moreover, OSHA and MSHA have training requirements to ensure safety in mining areas.

With respect to emergency response situations pertaining to treatment, storage, and disposal of chemical, OSHA “mandates that in some instances emergency response operations undertaken to respond to releases of hazardous substances must meet particular standards [and] two applications could potentially apply to mines:

- “Operations involving hazardous wastes that are conducted as treatment, storage, and disposal (TSD) facilities.

- “Emergency response operations for releases of, or substantial threats of releases of, hazardous substances without regard to the location of the hazard” (Savit & Abrams, 2001, p. 119).

In this case, the first facilities above require an “emergency response plan and training” (p. 119). They could not just be implemented without proper training as mandated by OSHA.

Savit & Abrams (2001) further cite the difference between MSHA and OSHA, in that:

When MSHA does not have enforceable standards, the agency refers matters to OSHA for appropriate action. However, MSHA has promulgated regulations governing mine rescue teams, which detail the requirement for training mine rescue teams and mine emergency notification plants” (p. 119).

The Clean Coal Technology Program

Clean Coal Technology Program is a program of the U.S. Department of Energy that “refers to a number of technological advances that make the burning process of coal cleaner by removing pollutants such as sulfur, nitrogen, and fly ash that can contaminate the air and water” (American Coal Foundation Glossary, 2007).

This is one positive effect of the regulation and the enactment of Congress and government over industries whose workplaces can cause illnesses to workers when not properly regulated.

The Clean Coal Technology Program is a continuing program of the US Department of Energy that started in 1985. The objective is to reduce substantially the emission of pollutants into the atmosphere.

The Clean Coal Technology Program of the Department of Energy, United States includes:

- “Advanced technologies that have dramatically improved the economic and environmental performance of flue gas desulfurization systems for SO2 control. By-product gypsum is now recovered for sale as wallboard, thereby eliminating a major waste disposal problem.

- “NOx reduction technologies that have been or are being retrofitted to a large segment of the nation’s coal-fired power generating capacity. Low-No x burners now cost a fraction of the cost of No x pollution controls available in the 1980s.

- “New power generation systems now in commercial operation, based on coal gasification. These systems are among the cleanest power plants in the world, with extremely low emissions of SO2 and NOx, and particulates.” (Department of Energy, 2001, p. 1).

In layman’s terms, CCT Program is to provide coal-based technologies that “minimize the economic and environmental barriers that limit the full utilization of coal” (Department of Energy, 2001, p. 1). These technologies reduce the emissions of SO2, Nox, and particulates.

The CCT program is the most comprehensive and ambitious program of the Department of Energy which is to fully utilize every available technology to prevent poisonous gases from escaping to the atmosphere, thereby becoming coal a reliable and clean energy source.

The United States, particularly its government, is being criticized by other countries because of industries that produce coal gas emissions. Environmental groups have issued statements every now and then for the government’s lack of concern for the environment, saying that there’s not much that is being done to institute measures to prevent global warming and climate change. It is undeniable that many of our major industries depend much on coal and fossil fuel as an energy sources.

The Department of Energy answers this with a positive note on its “environmental success story”:

“Three-quarters of the coal-fired capacity in the United States today uses low-NOx burners developed through DOE programs, significantly reducing emissions of one of the chief pollutants responsible for smog and ozone buildup. A portfolio of cost-effective NOx control technologies suitable for the full range of existing boilers is now available.” (Department of Energy, 2001, p. 1).

As soon as this becomes fully operational, we can expect other countries to follow suit. Developing and poor countries should be aided by rich and powerful countries for this to be effective, in order for our earth to have a fresh atmosphere free of the poisonous substances and other gases that trigger global warming. We can help reduce acid rain, global warming, and the emission of pollutants in the process of coal combustion.

On the other hand, there’s the question of the U.S. government’s negative attitude or clean-hand policy on the Kyoto Protocol. The Kyoto Protocol sets “binding targets for 37 industrialized countries and the European community for reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions” (UNFCCC).

It is to be noted that the United States, through past administrations, did not ratify the Kyoto Protocol. It had been implied by past U.S. representations that ratifying the Kyoto Protocol would hurt the U.S. economy.

“In February 2002, President Bush announced a U.S. policy for climate change that will rely on domestic, voluntary actions to reduce the “greenhouse gas intensity” (ratio of emissions to economic output) of the U.S. economy by 18% over the next 10 years” (The Encyclopedia of Earth, 2007).

There have been positive results on coal mining regulations, but as to other issues, such as greenhouse gas emissions, the government cannot commit itself even to an international forum.

Coal mine communications system

Coal mine Communications System is a different approach to communication. This is because it is not the conventional way of communication technology where a wire-based communication system can be applied. Such a system may fail due to fires and wires may tear down in deep excavations. A power failure may also occur in the process.

Cellular phones are not applicable because of the presence of different frequency signals in underground mines. Companies in coal mines employ a special cable called a “Leaky Feeder”, and other fiber optic cables. However, they also use “telephones, walkie-talkies, paging devices, and similar technologies”. (NIOSH website) A different kind of telephone cable is used in their communication, which is more resistant to fire, roof falls, and other natural forces. In case of explosions, the wires and other communication system devices do not give up but can be a tool in the subsequent process of rescue on trapped miners. Some devices like repeaters or leaky feeders are used to “permit a radio signal to cover a larger area” (NIOSH). Also, frequencies have to be selected properly and uniquely because of the presence of unusual frequencies in the mine. The Mine Safety and Health Administration screens and approves electrical communications devices in coal mines. (NIOSH)

Another communication system for coal mines:

- “Through-The-Earth (TTE) Communication Systems – resistant to roof falls, fires and explosions” (NIOSH).

- “Flexalert – Mine Radio Systems – Canada – uses a low-frequency electromagnetic field to convey information to miners wearing special cap lamp receivers.

- “PED Mine Site Technologies – Australia – a one-way TTE transmission system that carries text messages to miners underground” (NIOSH).

- “Wireless-mesh-network – applicable technology to the needs of underground coal mining” (Schiffbauer, 2006, cited in NIOSH website).

Conclusion

There are positive impacts of the regulation on the miners and the general public. But these results are the mere tip of the iceberg. True, the miners are taken care of, and there have been positive measures in controlling the effects of poisonous substances into the atmosphere. The general concern is control of greenhouse gas which is a long way to go for the United States.

Accidents and diseases, like black lung, silicosis, and pneumoconiosis, as a result of coal gas emission, continue to be the major concern of agencies mandated to supervise and regulate coal mining. However, these have been minimized and controlled through the creation of federal and state regulators as a result of the regulations. Accidents have continued once in a while; miners still get sick, although the number (of miners getting sick of occupational diseases) has been reduced considerably.

There are many agencies involved in the regulation and supervision of coal mining in the United States, and though some have overlapping functions, they serve their purpose. With new technology and modern approaches and designs to coal mining, the negative effects have been substantially controlled.

The government should not let up in its effort to control coal gas emissions as enforced by the country’s signatories to the Kyoto Protocol. There might be valid reasons for the U.S. government to not ratify the Kyoto Protocol, but it must send a strong signal to other countries global warming and climate change are one of its primary programs to preserve the world we live in.

The U.S. Department of Energy’s Clean Coal Technology is a positive step. Probably this is its answer to the international clamor for environmental preservation and to reduce the greenhouse gas intensity of the U.S. economy. We have to note here that this program is a long-term program. Immediate steps have to be implemented.

References

American Coal Foundation (2007). Glossary. 2009. Web.

American Coal Foundation (2007). History of coal in the United States. 2009. Web.

American Coal Foundation. (2005). Timeline of Coal in the United States. 2009. Web.

ArcelorMittal (2007). History. 2009. Web.

Ashford, N. A., & Caldart, C. C. (2006). Government regulation. In Levy, B., Wegman, D., Baron, S., & Sokas R., Occupational and Environment Health, Ed. 5, pp. 39-42. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

CNN.com (2006). Quecreek ‘miracle’ offered Sago families false hope. 2009. Web.

Department of Energy, United States Department of Energy (2001). Environmental Benefits of Clean Coal Technologies. DIANE Publishing. Pp. 1-7. ISBN 1428918841, 9781428918849.

Ghosh, A. K., Bhattacherjee, A. and Chau, N. (2004). Relationships of working conditions and individual characteristics to occupational injuries: A case-control study in coal miners. Journal of Occupational Health, 46: 470-478. 2009. Web.

Hayes, G. (2000). Coal Mining. Published by Osprey Publishing. pp. 4-5. ISBN 0747804346, 9780747804345.

International Labour Organization (1994). Recent developments in the coalmining industry by International Labour Office, International Labour Organisation Sectoral Activities Programme. International Labour Organisation Coal Mines Committee. pp. 5-9. ISBN 9221093301, 9789221093305.

Karmis, M. (2001), ed. Mine health and safety management. SME. ISBN 0873352009, 9780873352000.

Levy, B. S., Wegman, D. H., Baron, S. L., and Sokas, R. K. (2006). Occupational and environmental health: Recognizing and preventing disease and injury, 5th Edition, Published by Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 0781755514, 9780781755511.

McElfish, J. M., Beier, A. E. & Environmental Institute (1990). Environmental Regulation of Coal Mining: SMCRA’s Second Decade, Environmental Law Institute, ISBN 0911937358, 9780911937350.

NIOSH National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. Focus on Coal Mining: Brief Overview of Mine Communication Systems. 2009. Web.

PG&E (2009). Pacific Gas and Electric Company. Web.

The Encyclopedia of Earth (2007). Kyoto Protocol and the United States (Summary). 2009. Web.

Savit, M. N. & Abrams, A. L. (2001). Other Regulatory Requirements Impacting Mining. In Mine health and safety management, Karmis, M. ed. SME. ISBN 0873352009, 9780873352000. pp. 115-120.

UNFCCC. Kyoto Protocol. 2009. Web.

Union Pacific (n.d.). Historical overview. 2009. Web.

Weeks, J. L. (2006). Essentials of the mine safety and health administration. In Levy, B. S., Wegman, D., Baron, D. H., & Sokas, R. K., Occupational and Environment Health: Recognizing and preventing disease and injury, Ed. 5, pp. 40-42. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 0781755514, 9780781755511.