Introduction

Vitamin C is an essential micronutrient with many crucial functions in the body. Ensuring that the diet is rich in high-quality sources of vitamin C is vital because of its great benefits. Other than what is known about vitamin C (it prevents scurvy), it is a co-factor in physiological reactions, enhances the intestinal absorption of iron, and acts as an antioxidant (Bender, 2003).

Some of the life-threatening diseases such as atherosclerosis and cancer occur due to oxidative damage of tissues (Health Supplements Information Service 2010). Vitamin C works in tandem with vitamin E in its antioxidant activity. Vitamin C is oxidized to dehydroascorbic acid in a reversible reaction in scavenging for free radicals and regenerating the reduced form of vitamin E (α-tocopherol) (Al-Ani, Opara, and Al-Bahri 2007).

According to the Food and Nutrition Board (2000), the recommended dietary allowances (RDA) are 75mg/day and 90mg/day in adult women and men, respectively. The RDA for vitamin C in children (9-12 years) is 45 mg/day. The major sources of vitamin C include citrus fruits, tomatoes, potatoes, green leafy vegetables, brussels sprouts, pepper, and broccoli (Eitenmiller, Ye, and Landen 2008).

Adequate intake of vitamin C is a challenge to a significant number in Britain despite the fact that fruits and vegetables are readily available in the market (Health Supplements Information Service 2010). This leads to the research question whether processing might have an effect on the availability of nutrients and especially the more oxidative vitamin C. A lot of literature has shown the effects of processing on vitamin C levels. Some of the processing procedures like washing, peeling and blanching are the reason for loss of water-soluble vitamins where vitamin C is part.

Vitamin C is especially sensitive to pre-freezing treatments and canning hence special consideration is given to this important nutrient (Rickman, Barett &Bruhn 2007). Fruits however are not blanched but other processes such as transport and storage degrade some of these vitamins and especially the more sensitive vitamin C (Rickman, Barett &Bruhn 2007).

The levels of vitamin C in these sources however are subject to oxidative and enzymatic degradation and the final result is a compound (diketogulonic acid) with no vitamin C activity (Nyyssonen, Salonen & Parviainen 2000). Under standard conditions, the levels of vitamin C continue to drop over time. Regardless of too much research on the effects of processing on nutrient quality, comprehending the differences in vitamin C quality in different types of canned and frozen vegetables is somewhat complex.

Most researches analyse the effects of processing on nutrient availability in fruits and vegetables from a particular locality. This method reduces the effects of variability but it is not representative of the fruits and vegetables in the entire market since fruits and vegetables in the market come from different localities.

There are also different brands of fruits and vegetables. This project will assay for vitamin C in randomly selected vegetables from various markets in the region. Information on maturity, locality, and cultivar is necessary to help understand the results better. Previous reports have indicated that even though vitamin C gets damaged through food processing, what remains is enough to meet the body’s needs. However, this needs confirmation and the project described below will seek to clarify this.

Project aims and objectives

Aim

- To determine the effect of processing (freezing and canning) on the vitamin C content of peas and carrots.

Objectives

- To extract nutrients from the peas and carrots (frozen, canned, and fresh) by using trichloroacetic acid.

- To determine the absorbance of the colour generated once the extract react with folin ciocalteu.

- To establish the difference in vitamin C levels in the different types of peas and carrot samples.

- To determine the effects of freezing and canning on vitamin C in peas and carrots.

Experiment Design

This is a laboratory experiment and availability of vitamin C in fresh and processed (canned and frozen) peas and carrots will be determined by colorimetric method (Jagota & Dani, 1982). This project aims at determining if the levels of vitamin C in particular types of vegetables are different. The vegetables in question are carrots and peas. Some of these vegetables will be frozen while others will be in cans.

Each sample of vegetables will have three replicates to cater for reproducibility of results. Since canned and frozen vegetables come in different brands, I will randomly select three brands (General Mills, Tesco, and Waitrose) and each brand will have three replicates. I will end up having 9 samples of frozen peas, 9 of frozen carrots, 9 of canned peas, 9 of canned carrots but only 3 of fresh carrots, and 3 samples of fresh peas.

The levels of vitamin C in these kinds of vegetables will then be compared with vitamin C levels in fresh unprocessed carrots and peas. The colorimetric method is the most ideal method to use in this case because the samples being used are high in organic matter. This is because it is 100% efficient and does not face interferences from other available compounds. This method is also quick and simple to conduct. This technique follows the law by Beer-Lambert which stipulates a maximum concentration of 45 micrograms. The colour developed has a stability of up to 18 hours. This method, just like other vitamin C assays, makes use of its anti-oxidant ability.

Procedure

Reagents

- Trichloroacetic acid

- Folin-ciocalteu

- Extracts of:

- Canned peas from 3 brands

- Canned carrots from 3 brands

- Frozen peas from 3 brands

- Frozen carrots from 3 brands

- Fresh peas and carrots

Procedure

- Extraction of contents from the vegetables.

Extraction procedure

10g of each type of vegetable will be homogenized with 15ml trichloacetic acid (80%) in a centrifuge test tube. Add 10% of trichloacetic acid to 0.2 ml extracts of frozen, canned, and fresh peas and carrots in a test tube. Vigorously shake the tubes. Place the mixture in the test tubes in an ice bath for 5 min. Centrifuge the mixture in the test tubes for another 5 min at 3000rpm. The supernatants will be transferred cautiously into another test tube to avoiding swirling the precipitate. The extracts will then be diluted with distilled water. - Use 0.2ml of the supernatants from each sample to determine vitamin C amount.

- Dilute the extract to 2.0 ml with distilled water.

- Add 0.2ml of folin reagent to the extract and shake thoroughly. 0.2 ml of folin ciocalteu will be prepared by diluting 2.0M of commercially prepared folin with 10 folds of distilled water.

- The mixture will be left for 10 min at room temperature for reaction to take place completely.

- The absorbance of light by the samples will then be determined and maximum absorbance will be measured at 760nm. Results will be recorded for the purpose of sample analysis (interpreting the results on absorbance of colours from the colorimetric procedure performed on the samples).

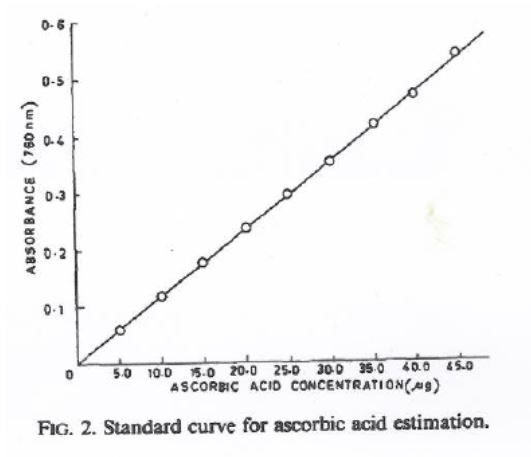

Sample analysis will entail using the results on absorbance to determine levels of vitamin C in the different samples. This is important for the statistical analysis to be performed next. - Standard solutions of ascorbic acid will be prepared from 0.05-0.7 ml of these solutions in 5-70 micrograms water.

- Folin will be added and procedures for 4 and 5 carried out as above.

- A standard curve will be designed as shown below from the absorbance of light at a specific wavelength based on the different concentrations of vitamin C.

- The standard curve shown below will be used to estimate levels of vitamin C based on the absorbance of each sample.

Notes

The concentration of the blue colour is tested by measurement of its absorbance of light at a specific wavelength of light. Since the colour/wavelength of the filter for the colorimeter is very important, a red colour will be set.

Ethical Considerations

Since this experiment entails selection of vegetables from certain stores, the different samples from the different stores will be anonymously labelled. This is meant to protect the rights of the businesses involved. However, the information can be used for research purposes, where no harm will be imposed to the involved businesses. For example, if any differences in the samples used are identified, the researcher may want to investigate the reasons behind this. Only under such circumstances will the actual names be used but discreetly (without disclosing to the public).

Statistical Procedure

Once the different estimates have been determined from the curve above, Microsoft excel 2007 will be used to perform statistical analysis. Data will be expressed in terms of means+ standard deviation (SD) of the minimum replicate of extracts from each set of samples. One way ANOVA will be used to determine differences in vitamin C between the different samples. A p-value of 0.05 will be used.

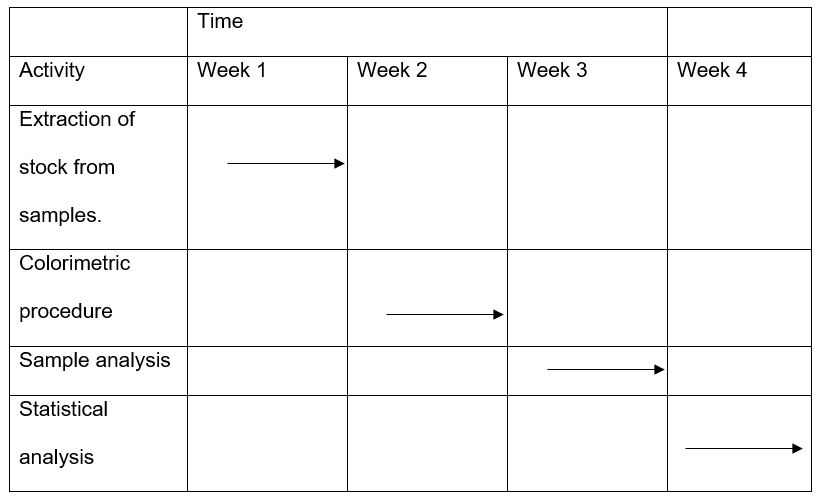

Time Plan

References

Bender, D. A. (2003) “Vitamin C (ascorbic acid)”. in Nutritional Biochemistry of the Vitamins. 2nd ed. ed. by Bender, D. A. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 357–384.

Eitenmiller, R. R., Ye, L., and Landen Jr., W. O. (2008) “Ascorbic acid: vitamin C”. in Vitamin Analysis for the Health and Food Sciences, 2nd edn. ed. by Eitenmiller, R. R., Ye, L., and Landen, Jr., W. O. Boca Raton: CRC Press, 231–289.

Food and Nutrition Board, Institute of Medicine (2000) Dietary Reference Intakes for Vitamin C, Vitamin E, Selenium, and Carotenoids, Washington, DC: National Academies Press. Web.

Jagota, A. K. and Dani, H. (1982) “A new colorimetric technique for the estimation of vitamin C using Folin Phenol reagent”. Analytical Biochemistry 127(1), 178-182.

Johnston, C. S., Steinberg, F. M., and Rucker, R. B. (2007) “Ascorbic acid” in Handbook of Vitamins, 4th ed. ed. by Zempleni, J., Rucker, R. B., and McCormick, D. B. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, 489–520.

Al-Ani, M., Opara, L., and Al-Bahri, D “Spectrophotometric quantification of ascorbic acid contents of fruit and vegetables using the 2, 4-dinitrophenylhydrazine method”. Journal of Food, Agriculture & Environment 3(3&4), 165-168. n.d.

Nyyssonen, K., Salonen, J. T., and Parviainen, M. T. (2000) in Modern Chromatogragraphic Analysis of Vitamins. ed. by Leenheer, A. P., Lambert, E., and Bocxlaer, J. F. New York: Marcel Dekker, 271–300.

Rickman, J., Barett, D., and Bruhn, C. (2007) “Nutritional comparison of fresh, frozen and canned fruits and vegetables. Part 1. Vitamins C and B and phenolic compounds”. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture 87, 930-944.