Introduction

Competition in any sector of the economy is beneficial both to the consumer and to the government. It is through fair competition that consumers are provided with choices and hence increased quality of products. However, companies always want to dominate the market share. To achieve this goal, some companies use unfair practices to edge competitors out of the market. Some of these unfair competition practices include unsustainable low prices, conspiracy to set prices that hurt competitors, or even limit production to influence rise in prices (Paul, Cadle and Yeates, 2010).

As companies gear up to compete over the dwindling size of customers, many companies are getting into unfair competition methods (Rossi and Volpin, 2004). While the competitive environment is conducive for the benefits of consumers, companies can employ tactics like unreasonable and highly subsidized prices to hurt competitors (Hilty and Henning-Bodewig, 2007). These prices may not be sustainable over a period of time. The goal of such a move is to woo customers into consuming products or services of the company at the expense of other companies.

While the objective of companies is to make profits, markets must be regulated by a neutral body so that companies do not result in unfair competition practices (Jones and Sufrin, 2008). These regulatory bodies comprise of players in the industry as well as government agencies. If competition is allowed to take its natural course, companies may be hurt each other through reduced revenues and hence reduced remittances to the government in terms of taxes and levies.

Beside, unfair competition techniques where a company lowers prices of products to unsustainable levels, other malpractices could include competing companies hoarding product(s) while anticipating rise in products’ prices. This causes an artificial shortage in the market. Due to forces of demand and supply, prices increase hence hurting consumers and denying government revenues.(Rossi and Volpin, 2004).

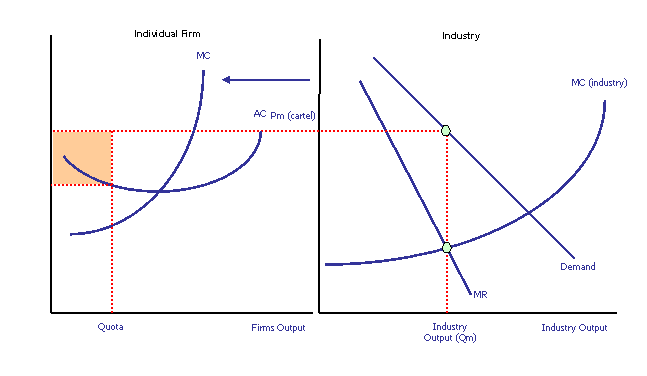

Other companies may form cartels, therefore, excluding other rival companies. These companies employ unjust trading techniques such as conspiracy to fix prices that may end up hurting other dominating players in the market (Fernando, 2010). If a section of companies that are competing ‘gang’ up against other companies without a neutral regulator, the market sector is likely to be hurt. Other unfair practices include putting unjust trading conditions that tie customers to the company or limiting production. For instance, in the telecommunication sector, companies have been seen to use unfair trading methods, where they limit the movement of customers into other networks through unfair conditions (Acutt and Elliott, 2001).

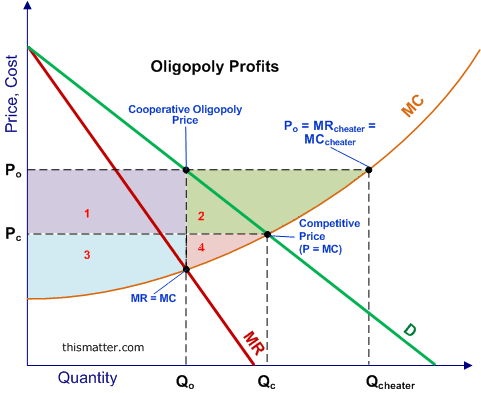

When there are few players in the sector, there is a real danger of the players conspiring to raise the prices at the expense of consumers. This is one of the effects of oligopoly. Consumer protection bodies must be ready to deal with such malpractices that may hurt the market (Hilty and Henning-Bodewig, 2007). Other practices that lead to the unfair competition are when companies agree to limit their production to cause an artificial shortage in the market. It is the duty of regulatory bodies to set rules and regulations that guide operations in the sector and evaluate how unfair competition is likely to hurt the market (Connor, 2008).

Regulation of unfair competition from mergers and acquisition in the UK

In the United Kingdom, regulations guiding competition in the market are set by the Office of Fair Trading (OFT) and Competition Commission (CC). The rules guide healthy competition between companies. In the Competition Act, 1998, businesses are prohibited by law from using uncouth practices that are not aimed at ensuring a competitive atmosphere within the sector (Hemphill, 2004). Companies are required to use fair methods like improvement of product, enthusiastic advertising, and promotional techniques without hurting other competing companies. According to the Act, competing companies are not supposed to form price cartels or conspire to fix prices, or discriminate between customers based on consumer segmentation (Dash, 2010).

On the other hand, a dominating company can use its position to control the market and therefore push competitors out of the market. According to the Competition Act, the law applies to companies that control more than 40 percent of the market share. OFT has powers to investigate and punish companies that may end practicing unfair trading practices. Both OFT and Member States’ National Competition Authorities (NCA) impose penalties to companies that may show tendencies to employ unfair competition practices. Penalties can include individual punishment to its directors or fines based on the global turnover of the companies (Fernando, 2010). Companies that are hurt by unfair competition are also allowed by law to sue the other company for unfair competition practices.

Regulatory body, OFT, acts on complains from players in the sector. Companies may not expressly agree to hurt their competitors but can act making trading fairly difficult (Motta, 2007). There are signs that show a company is applying unfair competition practices. Among the fair practices that a company can use to attract customers could promotional techniques like discounts and commissions, rewarding loyal customers, among many others (Rush and Ottley, 2006). However, there are other practices that point towards unfair competition. Companies can block new entrants into the market by controlling the suppliers. Competing companies definitely require similar raw materials for the products. However, companies that are established and dominate the sector can prevent suppliers from availing raw materials to other competing companies (Jones and Sufrin, 2008). Secondly, OFT and CC consider cases where companies lower prices such that charged cost is not able to cover the cost of production, as unfair trading practice. Thirdly, is formation of cartels. Cartels are companies that agree to cooperate instead of competing at the expense of consumers and other competitors (Paul, Cadle and Yeates, 2010). Cartels are responsible for fixing prices, agreement to limit production to increase the prices or market sharing.

OFT consider these serious offenses and can lead to heavy fines by the companies that are practicing these techniques. Competition can be reduced if competing companies form mergers or buy other competing companies in acquisitions (Moore, 2004). These techniques reduce players in the market and can lead to partial oligopoly (Waterson, 2003).

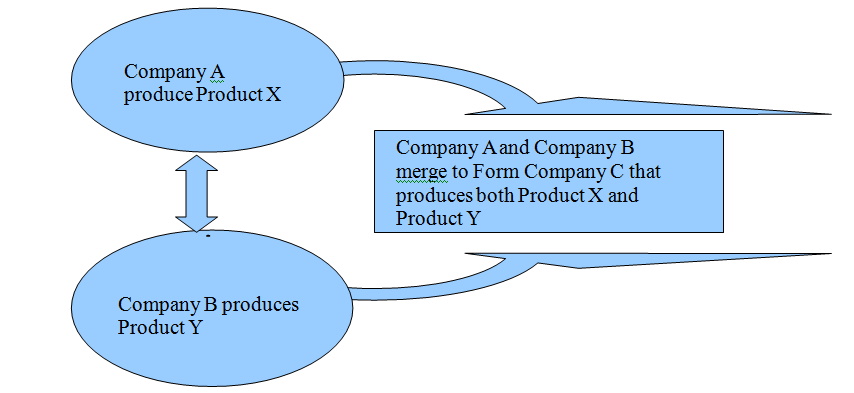

Mergers are when two or more companies producing similar product form a joint business venture (Connor, 2008). Mergers can be good in reducing production cost and improve efficiency of service delivery. But if a market sector does not have many competitors, mergers would definitely hurt consumers. Mergers in such a case will lead to higher prices, reduced quality of products and constrained choices of products by consumers. Mergers can also lead to monopolistic economy (De Vrey, 2006). In a monopoly, the sole company in the sector sets the price and hence consumers have no choice but to abide with company conditions even when the same product or service can be gotten at a lower price (Waterson, 2003).

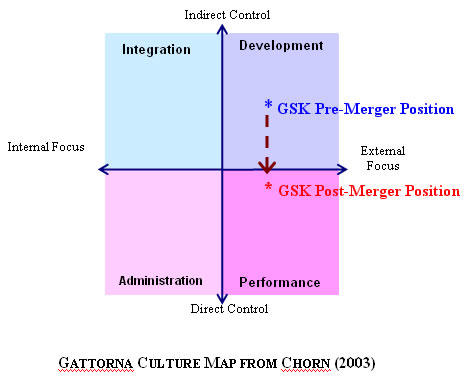

When a business merges with a rival (horizontal mergers), the companies produce products that satisfy similar needs of consumers. For instance when Glaxo and SmithKline merged, they did not cause any unfair competition in the market because there were many players in the medicines and drugs market. Or when Gales was acquired by Fuller’s, the market was not tilted to affect consumers because there are many players in the beer brewing sector. However when a business acquires another in a different distribution chain, this is considered to be vertical mergers. For instance when Ford Motor Vehicle company acquired Hertz Driving School was an example of vertical merger.

It is the work of OFT and CC to ensure that the market is not affected by either acquisitions or mergers. OFT advises against mergers that are likely to substantially reduce competition in the market (Rodger and MacCulloch, 2008). It is the duty of Competition Commission to turn down a request for merger if such a move does not improve the market but ends up hurting it. However, Secretary of State can also refer a case of merger to CC if such a joint venture is likely to hurt the security of the sate or cause instability in the financial systems. Though it is not expressly stated that companies must notify OFT before mergers, it is appropriate to notify the body to avoid pitfalls that may result from lawsuits of unfair competition practices. It is only these notifications that OFT use to evaluate whether such a merger would reduce competition in the sector (Cini and McGowan, 1998). Under the Enterprise Act 2002, OFT review mergers to establish the venture would lead to substantial lessening of competition. However, mergers may not be considered as being unhealthy if there is no company that complains to the OFT (Cini and McGowan, 1998).

After merging, companies cease to operate as competing entities and therefore operate under common leadership. Many mergers of small companies may not be referred to OFT for investigation. Mergers can only be investigated if they meet set criteria which include if the business being taken over has more than £70 million in turnover of controls or if two merging companies control more than 25 per cent of the market share (Cini and McGowan, 1998).

Enforcement of competition rules and regulations

When Competition Commission replaced the Monopolies and Mergers Commission in 1999, following the enactment of Competition Act 1998 and Enterprise Act 2002, competition issues were clearly defined (Rodger and MacCulloch, 2008). The commission was empowered to investigate mergers in respect to the effect on the economy, other competing companies and customers. The Enterprise Act also gave remedial powers allowing companies to take actions to improve competition.

Among unfair competitive practices include predatory pricing (unsustainable low prices aimed at pushing other competitors out of the market), excessive pricing (dominant players can increase prices unreasonably with no relation to the economic value of the products), fidelity rebates (when a dominant company rewards customers through discounts or rebates to retain them) and unreasonable refusal to supply (cutting off supplies without offering a convincing reason for the action) (Hemphill, 2004).

The UK’s Enterprise Act allows OFT to investigate market players and their effect on competition if mergers are effected. Companies are then referred to the CC for further investigations. It is the duty of CC to indicate whether mergers or acquisitions may distort or restrict competition in the sector (Hilty and Henning-Bodewig, 2007). Secret price-fixing and market sharing cartels are considered serious infringements under the laws governing competition in the European Union market (Motta, 2007). Due to negotiated trade agreements, companies from member countries are expected to adhere to the set rules and regulation that ensure fair competition among the players in a particular sector (Rush and Ottley, 2006). Companies dominating a particular sector are prohibited from exploiting their market muscle hence hurting trade in other member countries.

The Competition Commission (CC) ensures that industries are regulated to facilitate healthy competition among players in a particular sector (Cartwright and Schoenberg, 2006). According to the UK economic regulators report, under Enterprise Act 2002, OFT is mandated to review mergers with a view to establishing whether they affect competitive nature of the market. If a merger contravenes tenets of fair competition, OFT can prevent the merger from going ahead. This is meant to safe-guard the interests of consumers as well as ensuring the health of the market in the member countries within European Union (Accut and Elliott, 2001). For instance, if a merger in France affects fair competition in Germany, then the European Commission can stop the merger in the interest of member countries. Through negotiated trade agreements, member countries are required to adhere to the rules and regulations governing mergers and acquisitions.

Mergers are not necessarily between competing companies. As in vertical mergers and acquisitions, companies may merge even when they are producing competing products (Parr et al, 2005). Vertical mergers are unlikely going to lead to Substantial Lessening of Competition, but may benefit from efficiency in distribution of complementary products or services. However, vertical mergers can affect companies in merged companies if the competing ones do not have the capacity of the acquiring company (Worthington and Britton, 2009). In horizontal mergers, competition is reduced. This leads to fewer players in the market and constrained production. If the demand of products remain the same, prices of commodities or services is likely to shoot up hence affecting the consumers.

OFT and CC consider constrained production effect when investigating mergers and their effects in the market. Mergers cause unilateral effects leading to little choice of alternative products for consumers, increase in prices due to economies of scale with merged companies and therefore it becomes difficult for competing companies to respond to price increases without affecting their sales. Mergers eliminate or lessen competitive force in the market or lead to reduction of competitors hence consumers needs are not adequately addressed (Accut and Elliott, 2001).

While mergers may improve efficiencies, they can also hurt other competing companies. This may end up preventing new entrants into the market. Merged companies enjoy economies of scale and hence can afford to lower prices which other companies cannot sustainably recommend. Mergers can affect customers if such ventures reduce the choice of products due to the merging of competing or subordinate companies. Regionally, European Commission enforces competition rules. Member States National Competing Authorities like OFT and CC in UK, are mandated to enforce European competition rules (Rodger and MacCulloch, 2008). However, these rules do not hold individuals within a particular company liable for prosecution or other disciplinary measures. Through NCAs, member states can institute disciplinary proceeding targeting the company’s leadership that has breached governing rules.

Recommendations

Competition in any market is healthy. However, regulatory bodies act on competition malpractices depending on the complains they get in the sector. This means that if there are no companies that are ready to come out to oppose unfair competition practices, then regulatory bodies like EC, CC and OFT may not act on them. Being public bodies these institutions should be proactive in the interest of customers. Waiting for complains from competitors, can sometimes be counterproductive when companies are not ready to raise those complains or few players in an industry conspire to act unfairly for their advantage at the expense of customers. This means that consumers will continue to suffer in the hands of unscrupulous businesses.

Being market regulators of unfair competition OFT, CC and EC should institute investigations whenever there are mergers or acquisitions to safe guard the interests of customers. When unfair competition affect companies from other countries, individual directors should as well be held to account for malpractices in their companies where mergers, acquisitions or joint ventures leads to unfair competition in the sector and the region.

Conclusion

Companies are in business to make profits. One of the techniques to secure a large profit margin is to have a larger market share. Companies can result to mergers, acquisitions and joint ventures in an effort to reduce operating costs as well as utilize benefits of economies of scale. These mergers and acquisitions tilt the balance of competition in the sector. Consumers have fewer choices. These are actions that can hurt the economy if these ventures lead to Substantial Lessening of Competition. In controlling dynamics within business environment, a neutral body oversees the mergers and acquisitions.

In UK, CC and OFT are empowered by law through Enterprise Act 2002 to oversee mergers, acquisitions and joint ventures in a bid to control unfair competition practices. These independent public bodies are subject to the agreements of the region’s European Commission that require member countries to practice fair competition practices that do not hurt businesses from other member countries.

Regulatory bodies are mandated to check on unfair competition practices that may end up hurting businesses and economy, disenfranchising customers through exploitation with exorbitant prices, or unfairly locking out other competitors from business.

Under the European Commission each country must have its National Competition Authority as an independent body to oversee mergers and acquisitions. There are two types of mergers that these authorities must investigate to evaluate their impact in the market: horizontal and vertical mergers. In horizontal mergers, two companies producing competing products form an independent company, while vertical mergers refer to mergers of different companies producing different but complementary products or services. Regulatory bodies can grant or block mergers or acquisition depending on the impact such a move is likely to have on the entire market.

List of References

Acutt, M and Elliott, C. (2001). Threat-based competition policy. European journal of law and economics. Vol. 11, No.3, 309-317.

Cartwright, S and Schoenberg, R. (2006). Thirty years of mergers and acquisitions research: Recent advances and future opportunities. British Journal of Management. Vol. 17, Issue S1, S1-S5.

Cini, M and McGowan, L. (1998). Competition policy in the European Union. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Connor, J. (2008). Global price fixing. Berlin: Springer.

Dash, P. (2010). Mergers and acquisitions. New Delhi: I.K. International Publication House.

De Vrey, R. (2006). Towards a European unfair competition law: a clash between legal families: a comparative study of English, German and Dutch law in light of existing European and international legal instruments. Martinus Nijhoff, Boston: Leiden.

Fernando, A. (2010). Business ethics and corporate governance. New Delhi: Dorling Kindersley.

Hemphill, T. (2004). Antitrust, dynamic competition and business ethics. Journal of Business Ethics. Vol. 50, No. 2 127-135.

Hilty, R. and Henning-Bodewig, F. (2007). Law against unfair competition: towards a new paradigm in Europe? Berlin: Springer.

Jones, A and Sufrin, B. (2008). EC competition law: text, cases and materials. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Moore, G. (2004). The fair trade movement: parameters, issues and future research. Journal of Business Ethics. Vol. 53, Nos 1-2 73-86.

Motta, M. (2007). Competition policy: theory and practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Parr, N, et al. (2005). UK merger control: law and practice. London: Sweet and Maxwell.

Paul, D., Cadle, J and Yeates, D. (2010). Business analysis, 2nd ed., Swindon: British Informatics Society.

Rodger, B. and MacCulloch, A. (2008). Competition law and policy in the EC and UK. London: Taylor and Francis.

Rossi, S and Volpin, P. (2004). Cross-country determinants of mergers and acquisitions. London Business School. Vol. 74, Issue 2, 277-304.

Rush, J and Ottley, M. (2006). Business law. London: Thomson, Corp.

UK economic regulators. (2007). Great Britain, Parliament House of Lords. Select Committee on Regulators. London: TSO.

Waterson, M. (2003). The role of consumers in competition and competition policy. International journal of Industrial Organization. Vol 21. Issue no. 2 129-150.

Worthington, I. and Britton, C. (2009). The business environment, 6th ed., Harlow: Financial Times Prentice Hall.