Introduction

Finance has been the subject of global market confusion and unremitting controversies with matters of greater public and private concern facing unending challenges due to incompetent policies and regulations governing financial affairs.

The unprecedented hard economic epoch of the recent decades has hit the financial market, thus affecting operations of numerous companies globally through constantly augmenting defaults and losses (Ramsey 43).

Generally, one of the worldwide industries that have constantly suffered from financial crises and the related risks is the global construction industry where million of losses occur not only from the economic circumstances, but also due to unrelenting misfortunes that mar industrial growth.

In a bid to protect contractors from the rising financial risks that have become more eminent in the current decades, financial institutions are becoming proactive in providing risk transfer mechanisms in the form of surety. Despite decades of surety guarantees by corporations in the United States, little remains known to the public about surety. Therefore, this study explores construction surety bond underwriting risk evaluation.

Synopsis of a construction surety contract

The financial business world has grown exponentially for decades and become the most responsive industry that constantly provides substantial aid to other industries on risk related affairs. By operating slightly akin to the insurance firms, corporate sureties have emerged stronger in supporting risk related industries including the construction companies by providing surety bonds.

In simple terms as defined by CNA Surety, “surety bonds are three party instruments by which one party guarantees or promises a second party the successful performance of a third party” (1). These three parties or principles involved in the surety bonding include a surety (any financial institution), a principal (contractor) and an Obligee (owner) (Seifert 47).

Surety bonds involved in construction or bonding construction companies are contract surety bonds. Obviously, construction is a challenging and risky business that possibly can result into huge losses to constructors and owners is not well handled. Construction surety bonds typically prevent owners from financial and resource related risks that likely occur during project construction.

In its broadest understanding, construction surety bonds normally provide assurance to Obligee or project owners that contractors are capable of performing or completing the project on due time, within the stipulated budget and in the desired design requirements (McIntyre and Strischek 30).

On the same note, construction surety bonds are capable of assuring the venture owners that the contractor will complete the project and pay all the specified subcontractors, material suppliers and manual workers as expected (McIntyre and Strischek 30).

Research has identified three common forms of construction surety bonds namely bid bonds, performance bonds and the payment bonds that are common in a large construction spectrum. A bid bond is a construction surety bond that provides financial assurance that the contract is for good will, in desired price and required performance and payment bonds.

Performance bond provides “the owner with protection against financial loss in a circumstance where contractor fails to complete the project and meet terms and conditions of the contract., while payment bond ensure that the constructor makes all payments to suppliers, subcontractors and laborers” (Jenkins and Andrew 2).

Background to the U.S. construction surety industry

Perhaps the United States stands out to be among the most advanced countries that have integrated systems to protect innocent civilians from malicious service providers, including malevolent project managers and contractors.

The U.S. construction surety industry has expanded exponentially in the current decades and its history and background is long, and its fate has been a mixture of success and failure (McIntyre and Strischek 31).

The U.S construction surety industry premiered centuries ago and financial corporations have been offering surety bonds for quite a while, before the government decided to intervene as a service-consumer protection intervention.

According to Surety Information Office (1), the year 1893 saw the U.S government, through Miller Act Section 270a, placing a legal mandate to all contactors on public works contracts to acquire surety bonds that guaranteed their constancy in undertaking projects and masking dully payments to all subcontractors and suppliers on project completion.

The importance of getting into construction agreements and contracts began at this moment.

By the U.S. Government imposing Miller act, one significant issue emerged from this rule. According to Surety Information Office (1), “the Miller Act (40 U.S.C. Section 270a) requires performance and payment bonds for all public work contracts in excess of $100,000 and payment protection, with payment bonds the preferred method, for contracts in excess of $25,000.”

In subsequent moments, approximately fifty American States, including Puerto Rico and District of Columbia began enacting this act. Since this enactment, corporate financial institutions initiated massive campaigns of attracting contractors in such business activities by making the surety industry quite a competitive sector throughout 1990s when the American economy thrived.

Under the strong economy, the contractors remained busy and with minimal failures until the entire world began experiencing economic crunches. Unfortunately, the profitable bonding business became more overwhelming and centered attention for new entrants into surety leading to excess and gratuitous competition within the surety industry that has finally remained shaky 2000 due to high-profile corporate failures.

Principles of Premiums and losses

While trying to understand underwriting of surety bonds in the construction industry, premiums and losses are two financial terminologies associated with underwriting of surety bonds. The U.S surety bonds, similar to the insurances, have premium and loss terminologies, which represent certain fees.

Unlike the insurance premium, surety premium refers to service fee or service charge determined based on anticipated losses (Grovenstein et al. 356). Losses are unforeseen financial risks that may result from contractors failing to complete the project as per expectations, or even other uncertainties related to project construction.

In the case where the surety industry considers risks from the construction company are unpleasant, the financial institution, which is normally the surety, may have to deem a number of alternatives.

According to contract bonding principles, McIntyre and Strischek affirm that some of the alternative that assists in minimizing loss chances in sureties is raising premium charges, raising deductibles, reducing bond coverage, intensify underwriting standards or even quite completely from the bonding deal (30)..

Perceived significance of surety contract bonding

Since the advent of surety contracting and bonding into the U.S federal public works, much has protracted that has led to surveyors considering the imperativeness of surety contract bond underwriting. Surety bonding is a process that involves risk sharing through a business-integrated program that involves several mutual terms and conditions for all the three parties involved (Jenkins and Andrew 1).

In actuality, there is no better or rather practical alternative of defending the private and the public against financial loss. On the other hand, financial institutions depend on public and private sectors to generate revenues for their survival.

Surety bonding on construction favors all the three principals in the contracting deal (Dunn and Sedgwick 15). For the owner, protection from financial loss, safety of the construction and smooth progress of the project is what becomes major benefits in due completion of the project (Ramsey 42). Three contract surety bonds have been supportive in assisting Obligee in undertaking their projects successfully b considering the success of the bonding.

The owner believes that the bid bond, the performance bond and the payment bond are core movers to the success of the project. McIntyre and Strischek assert, “Surety bonds assure project owners that contractors will perform the work and pay specified subcontractors, laborers, and material suppliers in accordance with the contract documents” (30).

The contractors (principals) also rely on the surety contract bond underwriting in a number of ways that may deem significant while undertaking their contracting process. During the underwriting process, the contractor feels assured of owner’s cooperation in terms of payment as cases of exploiting contractors seem outdated since the financial institutions scrutinizes owners financial capacity comprehensively.

Since the surety corporations have the financial stamina to cover any improprieties resulting from Obligee, the contractor feels assured of getting all the stated pay (Dunn and Sedgwick 15). The surety or the guarantors who are large financial institutions normally receive a financial benefit and commercial reputation over the surety industry since premiums have the potential of chaining the corporate improvement of the firms.

Essential information for underwriting a contract bond

Underwriting a contract bond has been a quandary for the three parties, with both of them having worries over the successfulness of bonding and the fate of the project under construction. As noted by Glaser, Piskorski, and Tchistyi “mortgage underwriters face a dilemma: either to implement high underwriting standards and underwrite only high quality mortgages or relax underwriting standards in order to save on expenses” (186).

All parties involved in undertaking the contract bonding must observe several parameters before concluding on ways to undertake the surety bonding. During the process, the corporate sureties are normally at higher risks since they are responsible for monitoring and assessing the capabilities of the two parties in the contract bonding (Sacks and Ignacio 46).

Nonetheless, it is worthwhile that all the three principles consider seeking legal advice and embedding their bonding procedures through legal frameworks that likely reduces chances of uncertainties. The two (principals and surety) with their underwriters and producers have the accountability to oversee all the procedures of the contracting process.

What contractors and their producers must know

Subsequent to a comprehensive coverage of all conditions, terms and procedure of signing the contract bonds, a greater responsibility rests upon the contractor companies and the surety companies as the owner waits in anticipation. As the surety depends on surety company underwriter to undertake a follow up on the contract and plan, the contractor company relies on the producer, who forms part contractor’s external advisory group.

The producer is one of the integral players in the contractor’s advisory team and to avoid performance-related risks that may hamper completion of the contract the producer plays an important part. The contractors company must consider the following qualifications from the producer: the producer must be familiar with the local, provincial and national conditions and trends within the surety market.

In addition, Ramsey (42) asserts that the producer must posses accounting and finance knowledge, respect and a reputation for integrity, knowledge of the contract law and their documents, substantial experience in management practices and strategic planning among other fundamental aspects.

They must understand that the contracting business involving construction company is quite challenging and with numerous uncertainties. For any successful contracting company, understanding of business risks is imperative and this aspect aids in evaluating and assessing the kind of contract bonding that firms associate with during their operations.

As suggested by Ramsey, “taking any and every job available is not a wise strategy” (44). A construction company must understand all the uncertainties including external construction risks as weather, natural hazards, material prices, or supplier’s inconveniences and owner’s-related risks, as well as internal risk like equipment failures, staff problems and capital fluctuations.

This move is normally the best way of evaluating and managing their risks since it enlightens the company on the genuine projects to pursue and the contract bonds to sign.

According to Fayek and Marsh (3764), the contractors must also rely on a sustainable legal expertise team that scrutinizes the owner’s financial potency, as it is normally a challenge for contractors to access data pertaining to owners financial and banking secrets that sureties have.

What surety and their underwriters must consider

In the context of undertaking the construction bonding process, the sureties that involve corporate financial institutions are the core movers and principals of contract bonding. Apart from the main surety in the bonding process, two actors as mentioned earlier are important in the process of surety contract bond underwriting: an underwriter and a producer, who form part of the entire process (Stevens 440).

An underwriter is a professional who works directly for the surety company that has offered to provide bond and undertake the obligation. After a successful collection of the necessary information pertaining to the contract, the bond producer presents the information to the surety company underwriter, who is responsible for making a follow up of the plan for the surety company (Ramsey 44).

The underwriter is the most integral person in the advisory team of the surety company. Ramsey) asserts, “The surety bond producer works with the surety company’s underwriter to ensure that the contractor is bondable and capable of performing the work and paying all parties” (44).

In the context of underwriter’s duties, the following are the primary activities undertaken in underwriting by the surety company underwriter. Firstly, the underwriter has the accountability to determine if the contractor possesses the financial potency to support the contract all through.

Secondly, the surety company underwriter ensures that the contractor has a positive historical record of paying subcontractors and suppliers immediately (Ramsey 44). Finally, the surety company underwriter ensures that the contractor possesses a good rapport with the banks and other financial institutions.

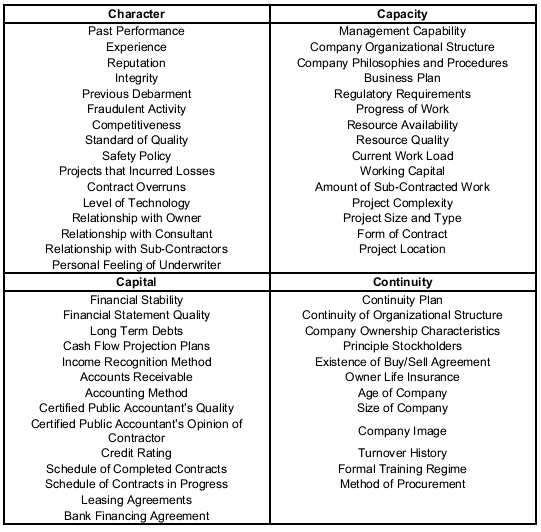

In simplest financial terms, underwriting standards of nowadays surety market emphasize on three important Cs representing capitals, capacity and character in the underwriting process and in understanding the contractor’s business. Since a surety bond acts as a bank credit in several ways, it is important for contractors to have a good reputation since contractors have a challenge of accessing debt capital (Seifert 49).

The underwriter also peruses through the contractor’s fiscal year-end statements including balance sheets, cash flow statements, and income statements among others. The table below summarizes the contractor evaluation criterion.

(Source: Fayek and Marsh 3766).

Project specific risk factors affecting contract bond underwriting

While trying to engage in the surety contract bonding and agreeing to the terms and conditions governing construction under contracts, the three parties especially the contractor in this case must understand the risks associated with contract bond underwriting.

This element explains the reason why the bond producer is an integral actor in the surety contract bond underwriting process in defense of the contractor as this professional recommends an accountability line of consistency regarding the contractor’s competence.

Two important forms of risks have been in constant discussions over the existence years of surety industry and contractor’s business, and these are project-specific related factors and performance-related risk factors.

To begin with, a construction industry is a challenging field of professionalism as it associates with numerous risks (Cummins 28). As guarantors are currently targeting mega contractors with large cumulative programs that are highly perilous, risk in itself is a unique issue and very few constructions complete successfully without encountering jeopardy.

As postulated earlier, the underwriter examines the capital, capacity, and character of the contractor; nonetheless, the forth c has emerged in the recent studies that denote continuity. The continuity in the case of construction may remain hampered by uncertainties. Project specific risk factors are precarious issues that associate with the project itself and contractors are normally unaware of the unforeseen uncertainties.

The project owners will always deem a project successful if the contractor manages to complete it within the stipulated time, designed budget and all other requirements (Grovenstein et al. 159). Project-specific related risk factors may involve natural catastrophes, delays in the supply chain or material deficiency, change in the material prices or even owners lack of cooperation.

This aspect explains the reason behind the existence of payment bond that ensures that the owner’s project continues despite the failure of the contractor in paying sub-contractors, laborers, and suppliers (Vedenov, Epperson, and Barnett 450). Project-related risk factors, especially natural ones have been the most challenging to control in the surety bonding.

Performance-related risk factors affecting contract bond underwriting

Performance related risk factors are uncertainties affiliating with the incapability of contractors to complete the desired project in the requirements highlighted in the contract bonding agreement (Strischek 31). Within the tripartite bond agreement, the caution and worry here is upon the owner of the project under construction and more worse to the surety company.

Some contractor’s performance faith has been questionable within the public and to ensure that contracts have remained successful through surety contract bond underwriting, the performance bond emerged (Seifert 48). While trying to understand the concept of performance related risk factors in the contracting process, management practices and strategic planning as contractor evaluation criterion emerged from this point.

Performance in the context of surety contract bond underwriting refers to the contractor’s aptitude in completing the agreed project. Some of the common performance related factors may include the contractor’s management delinquency, poor or lack of business planning, lack of contract performance frameworks, project complexity as well as obstructing company philosophies and procedures, most of which are avoidable.

How to make an appropriate bond underwriting decision

The appropriateness and successfulness of any bond underwriting between the three parties depends on a number of issues that surety companies must always consider before making a decision into the bonding. “Sureties and bankers have much in common.

McIntyre and Strischek postulate, “Both industries underwrite risk to contractors, and both have enjoyed the good time profits of the cycle’s expansion phase and suffered the losses during its contraction phase” (36). Therefore, analyzing risks involved in contract bonding becomes important.

However, in certain circumstances, financial organizations have found themselves into the traps of fraudster and money swindlers who pretend to be contractors from reputable companies, leading to serious financial losses (Glaser, Piskorski, and Tchistyi 188).

Despite the fact that there are very few decision-support models existing among financial institutions that are sureties and this aspect has resulted into numerous problems concerning contract bond underwriting (Stevens 456). As postulated earlier, corporate sureties should use a number of procedures in determining the probability of having attractive returns from a contract.

Before making a decision to engage in any contract bonding practice with the other two parties, viz. the project owner and the contractor, numerous things appear significant for consideration. Before anything else, the financial institution must scrutinize owner’s financial capacity including his/her willingness to pay all expenses incurred in the project and his/her previous behavior with the bank or surety (Ramsey 44).

In the beginning of the initial phase, the company must consider hiring or employing a competitive underwriter with appropriate knowledge in all forms of surety conditions, who will deal confidently with the contractor’s producer to avoid incurring financial losses.

Bearing in mind that the financial institution will be taking all the liabilities and obligations for the owner, a legal advisory team must prevail to provide information and make all follow ups of the required legal procedures while undertaking the construction bonding (Grovenstein et al. 359).

The financial organization must acquire proper background knowledge and assess the previous character of the contractor on the earlier contracts and agreements. All documents concerning the contractor’s latest fiscal year-end statements must exist in this assessment to provide assurance that the contractor has been loyally paying all sub-contractors, laborers, and suppliers within the slated time.

The financial institution, which is the corporate surety, must ensure that the underwriter assess “the contractor’s latest fiscal year-end statements by examining the accountants’ opinion to review the audit or compilations” (Ramsey 45).

They should also assess balance sheet to evaluate the working capital, income statements to estimate gross profits from previous contracts as well as cash statements to appraise operating cash flow among other important construction bonding documents before deciding on the bond agreements (Seifert 49).

On finalizing, the surety company underwriter must also consider analyzing the possible risk factors associated with the bonding and ensure they depend on a decision support model in their making their final agreement on the contract.

Conclusion

Conclusively, there has been substantial literature existing concerning surety bonding in the construction industry yet understanding important procedures in the construction bonding process has been a challenge. Surety companies are the most parties that are at a greater risk of failing in the surety bonding if proper securitization of the owner and the contractor’s intentions in the bonding deal are unknown.

Sureties with successful transfer of construction risk have always considered the attractiveness of the risk transfers. Companies engaging in surety bonding normally target the jumbo rates in the premiums, which normally come from seriously risky ventures, and if proper caution lacks in making the appropriate decision in the bonding process, the sureties may be putting themselves into great financial uncertainties.

Works Cited

CNA Surety 2005, Surety ship: A practical guide to Surety Bonding. Web.

Cummins, David. “Cat bonds and other risk-linked securities: state of the market and recent developments.” Risk Management and Insurance Review 11.1(2008): 23-47. Print.

Dunn, Jonathan, Irvine Sedgwick. “Letters of Credit, Bonding, Guarantees and Default Insurance: Hedging Bets in a Roller-Coaster Market.” American Bar Association 15.2 (2013): 1-17. Print.

Fayek, Aminah, and Krista Marsh. “A decision-making model for surety underwriters in the construction industry based on fuzzy expert systems.” Journal of Construction Engineering and Management 1.1 (2006): 3763-3772. Print.

Glaser, Barney, Tomasz Piskorski, and Alexei Tchistyi. “Optimal securitization with moral hazard.” Journal of Financial Economics 104.2 (2012):186–202. Print.

Grovenstein, Robert, Francis Sirmans, John Harding, Sansanee Thebpanya, Geoffrey Turnbull. “Commercial mortgage underwriting: How well do lenders manage the risks.” Journal of Housing Economics 14.2 (2005): 355–383. Print.

Jenkins, Robert, and Wallace Andrew 2005, Construction Bonds: What Every Contractor and Owner Should Know. Web.

McIntyre, Marla, and Dev Strischek. “Surety bonding in today’s construction market: changing times for contractors, bankers, and sureties.” The RMA Journal 87.8 (2005): 30-36. Print.

Ramsey, Marc. “Surety Bond Producers and Underwriters.” The RMA Journal 91.8 (2009): 42-45. Print.

Sacks, Arianna, and Correa Ignacio. “Underwriting: The Harvard Student Journal of Real Estate.” The Harvard student journal of real estate 1.1 (2011): 1-116. Print.

Seifert, Bryan. “Sustainable Buildings and the Surety.” Real Estate Issues 33.3 (2008): 47-52. Print.

Stevens, Glenn. “Evaluation of Underwriter Proposals for Negotiated Municipal Bond Offerings.” Public Administration & Management: An Interactive Journal 4.4 (1999): 435-468. Print.

Strischek, Dev. “Underwriting and Monitoring Consideration in Lending to Contractors Today.” The RMA Journal 86.10 (2004):31-32. Print.

Surety Information Office. n.d. 10 Things You Should Know About Surety Bonds. Web.

Vedenov, Dmitry, James Epperson, and Barry Barnett. “Designing Catastrophe Bonds to Securitize Systemic Risks in Agriculture: The Case of Georgia Cotton.” Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics 31.2 (2006): 318-338. Print.