Flight Safety

Generally, safety is a concept ingrained in the human mind. For most people, safety is considered to be the absence of danger. Safety is something related to all human activities and, therefore, every civil society is organized or should be organized to guarantee public safety in relation to one’s own or other’s activities.

For this reason, human activities that could cause damage to persons and properties are controlled by national states through regulations (Florio, 2010).

Specifically, flight safety can be defined as those plans that are incorporated into daily flight operations to serve as a means of ensuring that passengers are always safe (Bledsoe & Benner, 2006).

Contingency Plan

A contingency plan stipulates how an organization intends to respond to events that disrupt normal operations (DIANE, 2004). It should be a well articulated strategy document designed to define actions that should be taken in the event of an emergency (Geering & Amanfu, 2002).

The goal of contingency planning is to protect life and property by identifying the risks associated with an event and developing a plan of action to minimize those risks (PC, 2010). According to Balanko-Dickson (2006), the purpose of a contingency plan is to enable one to think ahead about the potential risks and plan how to respond, manage and act when specific events occur.

Taking time to conduct a risk assessment in advance allows the management teams to think through possible scenarios, define the implications, and plan a response. Generally, a contingency plan is an essential component in the aviation industry and all practitioners must have one in place to be used when necessary.

A good contingency plan will provide the response team with clear instructions on what should be done when faced with a problem (Socha, 2002). Traditionally, organizations will develop contingency plans as a means of protection against loses (Myers, 1996).

Ideally, there should be a contingency plan for any eventuality so as to ensure the safety of everyone. Airports and planes may be affected by natural disasters caused by weather and volcanic eruptions, or lengthy onboard ground delays, among others. This paper discusses a contingency plan to deal with lengthy onboard ground delays at the Generation Next Airport.

Lengthy Onboard Ground Delays

Lengthy onboard delay refers to the holding of an aircraft on the ground either before taking off or after landing with no opportunity for its passengers to deplane.

Who is affected by the Delays?

Lengthy onboard ground delays may be caused by severe weather, failed air traffic control programs, airport service issues, or airline operation difficulties. Delays can affect a single flight or multiple flights at one or many airports. They can also affect a single airline or airport or many airlines and airports.

Causes of Lengthy Onboard Ground Delays

Most causes of lengthy onboard ground delays are events that take airlines, airports, and air traffic control programs by surprise and beyond their preplanned and scripted procedures. A vast majority of the delays may be caused by events in other airports, and unpredictable variables such as weather and equipment or utility failures.

While onboard ground delays may have common causes, the exact nature and characteristics of specific delays may be turn out to be quite different. It is therefore important to ensure that contingency plans are flexible enough to account for the differences when defining and responding to ground delays.

Locations of Lengthy Onboard Ground Delays

Lengthy onboard ground delays generally occur during departure or arrival at large airports, or because of unplanned diversions at small airports (Swanson, 2011).

Mitigating Lengthy Onboard Ground Delays

The key to mitigating the effect of lengthy onboard ground delays and to ensure successful customer service during such delays is communication, collaboration, and coordination among airlines, airports, government agencies, and other aviation service providers.

These efforts are essential to reducing the frequency, duration, and impact on passengers of lengthy onboard ground delays. It is only by working together that this can be accomplished successfully.

It is important to note that each lengthy onboard ground delay event is unique, and airlines, airports, government agencies, and other aviation service providers will benefit most if individual contingency plans account for the different characteristics in adapting to changing conditions.

Passenger Needs

The needs of passengers’ onboard an aircraft or in an airport terminal during lengthy onboard ground delay events vary and normally require the attention of more than one party.

By understanding the needs of passengers during such delays, airports, airlines, government agencies, and other aviation service providers will be better placed to offer an effective response.

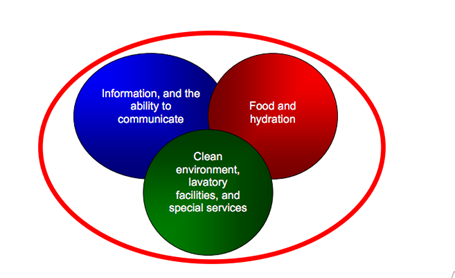

Figure 1 below shows basic customer needs and what is required to meet them while passengers are delayed in an aircraft or an airport terminal.

Figure 1: Basic Passenger Needs (Adapted from ACPE, 2008)

As depicted by the diagram, passengers affected by lengthy onboard ground delays generally require information which may include deplaning options, ability to communicate with friends, family, or colleagues, food and hydration, lavatory facilities, a clean environment, and other special services, as required.

The Contingency Plan

The stages outlined here provide a brief description of the contingency plan to deal with lengthy onboard ground delays at the Generation Next Airport. The main focus is to mitigate hardships for airline passengers during lengthy tarmac delays.

The plan contains separate sections covering maximum hold times during aircraft tarmac delays, provisioning of adequate food and water, medical attention and lavatory facilities during delays, communications to passengers, and an assurance of sufficient resources to implement the plan (VA, 2011).

The different steps of the contingency plan are briefly explained below. More details are presented much later.

On Aircraft Delays

Whenever there are delays, No aircraft will be allowed to remain on the tarmac for more than three hours before allowing passengers an opportunity to alight unless there is a safety or security related reason why the aircraft cannot leave its position on the tarmac to deplane passengers or the Air Traffic Control (ATC) advises that returning to a gate or any other disembarkation point would significantly disrupt airport operations.

For international flights, Virgin America will not permit aircraft to remain on the tarmac for more than four hours, subject to the safety and security related exceptions set forth above.

To accomplish this directive, Generation Next will make the following assurances for domestic and international flights.

- For domestic flights

When an aircraft has been on the tarmac for two hours, from the beginning of aircraft movement, the pilot in command will coordinate with the Operations Manager and local airport operations to arrange for a gate or hard stand, and will return to that gate/stand as soon as practical in order to deplane guests, unless it is evident that the aircraft will be able to depart the airport within 30 minutes from that two hour point.

Generation Next will not permit an aircraft to remain on the tarmac for more than three hours unless the PIC determines there is a safety or security related reason why the aircraft cannot leave its position on the tarmac to deplane guests or the air traffic control advises that returning to the gate or another disembarkation point would significantly disrupt airport operations.

- For international flights

When an aircraft has been on the tarmac for three hours, from the beginning of aircraft movement, the pilot in command will coordinate with the Operations Manager and local airport operations to arrange for a gate, and will return to that gate as soon as practical so as deplane guests, unless it is evident that the aircraft will be able to depart the airport within 30 minutes from that three hour point.

Generation Next will not permit an aircraft to remain on the tarmac for more than four hours unless the PIC determines that there is a safety or security related reason why the aircraft cannot leave its position on the tarmac to deplane guests or if the air traffic control advises that returning to the gate or another disembarkation point would significantly disrupt airport operations.

Adequate Food and Water

Generation next will ensure that all aircrafts have adequate food and portable water on board. In case of a tarmac delay, Generation Next will provide food as well as portable water to all guests, without any charge, no later than two hours after the aircraft has left the gate or touched down at the airport, as the case may be, unless the PIC determines that safety or security considerations can not allow such services to be provided.

Adequate Lavatory Facilities

All aircraft at the airport should be equipped with three lavatories and at least one lavatory must be operational at any particular time. Each airline must ensure that all the lavatories are serviced prior to each flight.

In the event that all lavatories become inoperable during a tarmac delay, the airline will return to the gate as soon as practical or make other arrangements to immediately service the aircraft to return the lavatories to operating condition, to ensure operable lavatory facilities remain available while the aircraft remains on the tarmac.

Medical Attention

Each airline will be required to make arrangements for medical attention to be provided to those guests in need during a tarmac delay. All aircrafts should be equipped with emergency medical kits and all flight attendant be required to undergo first aid training.

Should a medical situation arise where the training offered and the material provided is inadequate to address the situation, the pilot in command shall be notified and a third party communication link will be established. Depending on the guidance issued by medical consultants, the pilot in command will determine if the aircraft will return to a gate for further medical treatment.

Communications to Guests during Tarmac Delays

On all tarmac delay flights, the pilot in command will ensure that all guests receive notifications regarding the status of the delay every 30 minutes while the aircraft is delayed, including the reasons for the tarmac delay, if known.

Guests will also be notified beginning 30 minutes after the flight’s scheduled departure time and every 30 minutes thereafter that they have the opportunity to deplane from an aircraft that is at the gate or other disembarkation area with the door open if the opportunity to deplane exists.

Sufficient Resources

Generation next will ensure that sufficient resources required to fully implement the contingency plan are made available. Through a coordinated approach, Generation Next will see to it that all areas of the contingency plan are fully implemented.

Coordination with Airport Authorities as well as TSA and CBP Personnel

The key to the success of a contingency plan during a ground delay is real time shared situational awareness among all airlines, airports, government agencies, and other aviation service providers at that airport. This is best achieved through continuous communication and coordinated response efforts.

The coordinated response usually follows a general time phased approach, as responders and managers join efforts to attack the problem. When developing the contingency plan, the ground delay committee should consider the response mechanisms already in place, the plans they support, and any existing standard operating procedures so as to be able to identify any gaps in the planning (Biggs, 2009).

The contingency plan procedure will include information on how to initiate a coordinated approach to dealing with the problem at hand, establish airline, airport, government agency, and other aviation service provider roles and responsibilities, identify resources required during the lengthy onboard ground delay.

Use airport wide shared communications, including conference calls, Internet communication, web technology, and existing databases available, when conditions warrant the use of such means of communication, initiate and maintain collaboration among all airlines, airports, government agencies, and other aviation service providers, attend to passenger needs onboard aircraft and, once the onboard delay ends, address passenger needs after deplaning, such as rebooking flights and finding local accommodations, collect customer feedback, debrief key airport stakeholders after an event, continuously improve the process through after event reporting, training, and incorporation of best practices.

Generation next will coordinate the contingency plan with airport authorities including terminal facility operators where applicable at each large hub airport, medium hub airport, small hub airport and non-hub airport it currently serves in the United States.

The Airline will ensure that any new markets entered after plan is implemented will be fully advised of the plan before any service begins (Riley, 1995). Generation next will also coordinate the plan with all its regular diversion airports.

Plan Amendments and Recordkeeping

The contingency plan may be amended at any time in order to decrease the time for the aircraft to remain on the tarmac or for delivery of food or potable water or any other important services. All the necessary records will be retained and kept safely for future reference. Table 1 will be used to capture the amendments made.

Table 1: Record of Amendments (Adapted from ICPPT, n.d.)

Steps to Ground Delay Contingency Planning

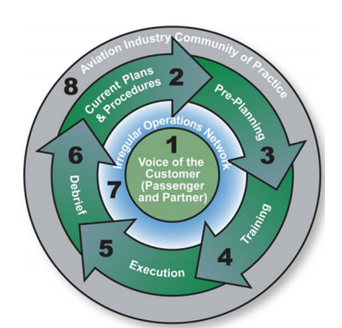

All airlines, airports, government agencies, and other aviation service providers should follow the steps outlined in figure 2 to establish a method for ground delay contingency planning and to set forth the procedures necessary to update and refine the process on an ongoing basis.

Figure 2: Ground Delay Contingency Planning Model (Adapted from ACPE, 2008)

Step 1: Voice of the Customer

The ground delay committee should coordinate with selected stakeholders to understand passenger needs during a ground delay. This will serve as an effective input in the development of the overall contingency plan. The committee should also ensure that passenger feedback and lessons learned are used to enhance the overall response effort.

The committee should therefore make every effort to establish a real time and cost effective means by which passengers will be able to express their concerns about delays to the relevant service providers during or shortly after an event.

In addition, aviation service providers will partner with other service providers to offer effective services during a ground delay (ACPE, 2008). The ground delay committee should therefore promote dialogue among all partners so as to avoid erroneous assumptions regarding preferred solutions for passenger and partner concerns.

Step 2: Current Plans and Procedures.

During this initial step, the ground delay committee should meet to review and analyze the status of the existing contingency plan. The outcome of this effort will be a coordinated contingency plan that will then be put into action to deal with the problem at hand. The committee will be required to conduct the following important activities.

- Risk Assessment

This is where by the committee performs a formal analysis or risk assessment so as to identify the types and scale of lengthy onboard ground delays and the associated airport and government agency response efforts. This assessment will then serve as the basis for all further activities.

- Gap Analysis

The committee will then proceed to carry out a review of the existing contingency plans to identify areas of the plan that may need enhancement. This will help to identify ways through which service providers will be able improve their activities. At this stage, the committee will be able to incorporate into its analysis the lessons learned from recent lengthy onboard ground delays.

- Enhance and Develop Plans and Procedures

After the analysis, the ground delay committee will then proceed to incorporate its results into a more coordinated contingency plan to be implemented.

Step 3: Pre-planning

At this stage, the ground delay committee will assess whether to include additional representatives on the committee, distribute copies of the revised contingency plan to all concerned airport service providers, and establish the steps to take to ensure proper resources and training are provided for successful execution of the contingency plan when a delay occurs.

Step 4: Training

Through appropriate training of key personnel, and relevant stakeholders, the ground delay committee will ensure that all service providers are implementing new policies, practices, and procedures in accordance with the reviewed contingency plan. Generally, service providers and government agencies will be responsible for their internal training efforts. The focus of the ground delay committee’s training should be to ensure that service providers and government agencies are able to provide a unified response during a delay.

Step 5: Execution

The ground delay committee will be required to effectively operate as a unified team during a delay by sharing situational awareness. In case of a ground delay, the committee will provide oversight for the overall response effort by facilitating a smooth interaction among all the service providers.

Step 6: Debrief

After a ground delay, the ground delay committee will be required to meet and review the effectiveness of the response effort, and incorporate lessons learned from the recent event into the contingency plan.

The committee also will also be expected to update the resource needs required to support future events, as well as update and administer revised training sessions as appropriate.

Step 7: Irregular Operations Network

The ground delay committee will schedule regular communications with its associated stakeholders and share the best practices identified during a ground delay as they become known to members of the community. Such dialogues may enable further enhancements to plans, resource staging, and training before the next delay.

Step 8: Aviation Industry Community of Practice

On a regular basis, the ground delay committee will collaborate with the larger aviation community to share experiences and lessons learned. This will enable the aviation community at large to learn from its fellow service providers who recently experienced a ground delay.

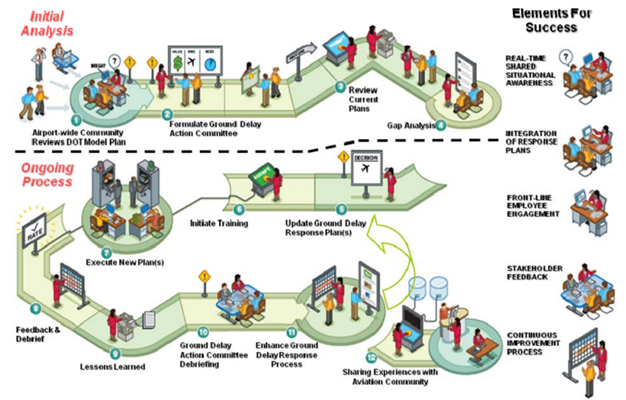

The above steps are all captured in figure 3.

Figure 3: Ground Delay Response Coordination (Adapted from ACPE, 2008)

Management of the Contingency Plan

The measures outlined in this contingency plan are applicable in cases of foreseeable events caused by unexpected interruptions in the airline operations caused by natural occurrences or other circumstances, which, in one way or another, may impair or totally disrupt the provision of air traffic services by Generation Next (ICPPT, n.d). The following arrangements will be in place to ensure that the management of the contingency plan gives the expected outcome.

Ground Delay Committee

The aviation service providers at each airport will be required to establish a ground delay committee comprised of representatives from all key aviation service providers. The committee composition will be based on the local aviation service provider structure and tailored to the local airport situation.

The committee central coordinating committee will be made up of an appropriate airport representative, who looks at the whole picture and is aware of the situation, an appropriate government agency representative, as well as public participants.

Other aviation service provider representatives will also form part of the team. Figure 4 shows the list of other people required so as to guarantee success.

Figure 4: Ground Delay Committee

Committee Goal

The goal of the committee will be to establish and enhance contingency plans through a collaborative decision making process. This is to ensure that all actions result in a unified level of customer care throughout all aviation service providers during the lengthy onboard ground delay events.

Committee Actions

The work of the committee will include developing the contingency plan, coordinate the pre-planning activities so as to agree on the committee’s actions before the delay, activate the contingency plan by agreeing on the committee’s actions during the delay, conduct debriefing sessions and ensure that the contingency plan is properly updated at the end of the delay, determine the most appropriate communication strategy to be used such as conference calls or face to face meetings.

Committee Responsibilities

The committee’s main responsibilities will include activating the contingency plan when lengthy onboard ground delays occur or are reasonably anticipated, facilitating shared communication for the entire duration of the delay, ensuring that the necessary resources are available during lengthy onboard ground delays, fostering an integrated and seamless approach among airport, airlines, government agencies, and other aviation service providers.

The committee will also focus on integration of business processes so as to ensure consistency and shared situational awareness. The committee will see to it that information is exchange information across all aviation service providers regarding who should provide appropriate services when a trigger event occurs.

The information exchange will also help to identify other stakeholders that may be requested to provide support services so as to deal with any outstanding needs identified. It will be critical for the committee to also recognize that airlines maintain operational control of their aircrafts.

Resources Required

There are various mechanisms that can affect joint communications and response during a lengthy onboard ground delay that require the appropriate resources from members of the ground delay committee.

The ground delay committee should take advantage of the existing resources and assets and this may include conference calls, internet communication and web technology and shared situational awareness tools, existing databases, and any other necessary facilities.

Airline Contingency Plan

The airline’s contingency plan will include a discussion and implementation of the following areas.

Communication

This is very essential and should involve all the stakeholders.

Communication with Passengers

Communication with passengers and all other affected parties will be frequent and very timely. This is the key to ensuring that any lengthy onboard ground delay is handled effectively and in a professional manner. Communication before, during, and after a lengthy onboard ground delay should be given a very high priority.

Airlines will also be required to make available any information relating to passenger resources and responsibilities in the event that travel delays are experienced.

This includes ensuring that information about the possibility of a lengthy onboard ground delay is made available to travel agents and directly to passengers before travel.

Passengers will also be provided with information about appropriate preparations for air travel such as bringing onboard essential items such as medical supplies, baby and child care products, communication tools, and other important items that are critical to health, nutrition, hydration, safety, and personnel comfort (Kazda & Caves, 2007).

With support from the airports, airlines will be required to develop processes for communicating the status of their flights to passengers using one or more of the available options.

Such alternatives include flight status lookup on the airline’s web site, telephone numbers that allow inquiries regarding the status of flights, proactive communications through voice or electronic messaging, up to date flight arrival and departure displays in airports, as well as information available to travel agents and others through global distribution systems.

Airlines will also be required to have processes that will provide up to date information to ensure that company employees will be able to pass on the information to passengers in a timely manner.

Communication with Service Providers

Airlines will be required to develop processes that will make it possible to directly communicate with other aviation service providers when a lengthy on the ground delay occurs.

Communication Procedures

When developing the contingency plan, the airline will be required to write procedures that will be followed to address communication with passengers regarding flight status, resources available in the event of a lengthy onboard ground delay, and information on planning for air travel as well as that for communicating with other aviation service providers.

Preplanning

Pre planning is a very critical step that must never be overlooked. To ensure success, good preplanning must be carried out. The planning may cover the following areas.

Anticipation of Lengthy Onboard Ground Delays

When practicable, airlines will choose not to board passengers until it is reasonably certain that the ground delay will not exceed a specific duration of time. However, lengthy onboard ground delays are unavoidable in certain situations. Therefore, when practicable, passengers will be advised to prepare accordingly for any eventuality.

Airlines will be required to make good use of processes to mitigate lengthy onboard ground delays and to minimize disruptions to customers as much as possible.

This should be clearly outlined in each airline’s contingency plan and should include allowing operations control center and station personnel to track arriving and departing aircraft on the ground, providing manual as well as automated alerting capability indicating lengthy onboard ground delays, making use of an airline diversion recovery process, in collaboration with air traffic control, as well as TSA and CBP, if this is applicable.

This process will allow the return of diverted flights to the destination airport when necessary.

Proactive Cancellation

Airlines may use an array of tools to reduce the incidence of lengthy onboard ground delays that are consistent with safety standards and an airline’s obligation to transport passengers.

One approach is to proactively cancel a flight when weather or other conditions make the likelihood of a lengthy onboard ground delay unacceptably high. In limited circumstances, a proactive cancellation may be appropriate if it minimizes the inconvenience to passengers and has a minimal impact on subsequent operations.

Before deciding to proactively cancel a flight, the airline should consider the travel season and the ability to rebook passengers within a reasonable timeframe.

If an airline determines that a proactive cancellation is appropriate, the airline should proactively communicate this information to the passengers by explaining the cancellation and the passengers’ options, preferably before their arrival at the airport. This will provide passengers with the ability to make informed decisions.

Every single airline should consider procedures for evaluating a situation to determine if a flight should be proactively cancelled, communicating such a cancellation to all passengers, rebooking or otherwise re-accommodating passengers who had been booked on flights the airline proactively cancelled.

Restriction Waivers

Another tool that airlines may use when certain conditions make travel disruptions likely is to offer waivers of ticket change and cancellation restrictions within a reasonable timeframe of the original travel date.

These waivers will allow passengers to change travel plans without penalty if the passenger determines he or she is unwilling or unable to bear the possible travel disruption, including a potential lengthy onboard ground delay.

In addition, airlines may offer customers various options for rebooking travel, such as airport kiosks, rebooking desks, ticket counters, travel agents, web sites, and call centers (Rothstein, 2007). This will allow passengers to choose the option that best meets their needs without having to queue at the airport, if this is a less desirable option for the passengers.

When developing a contingency plan, each airline should consider procedures for individually evaluating a situation to determine if a waiver of ticket change and cancellation restrictions is appropriate, communicating such a waiver to passengers, and rebooking passengers who take advantage of such a waiver.

Triggering Events

There are different types of triggers as explained here.

- Initial Trigger

The initial trigger takes place when the flight crew or airline operations control center is alerted to a situation that may result in a lengthy onboard ground delay. The initial trigger ensures key airline personnel are aware of the delay and leads to initial communication between the flight crew, airline operations control center, and local airline and airport operations personnel.

The flight crew should notify the onboard passengers of the possible onboard ground delay issues to the fullest extent possible and make flight status announcements no less frequently than every 30 minutes for the duration of the delay.

- Subsequent Triggers

Subsequent triggers take place when a predetermined period of time has passed after the onboard ground delay began. That time period may vary based on the airline, airport, or other variables. At that trigger, the flight crew and airline operations control center will evaluate the situation (Sharma, 2005).

The flight crew should regularly communicate with the onboard passengers no less frequently than every 30 minutes for the duration of the delay even if there is no change in status. At this point, the airline should notify other relevant aviation service providers of the delay and coordinate responses as necessary.

The airline also should assess gate and staffing availability. In some cases, the airline should consider remote pad deplaning if gates are unavailable, consistent with safety, passenger preference, and other situational constraints. The airline should notify the airport of the possible use of airport bus service and confirm response time.

- Deplaning Trigger

The timing and the circumstances for the deplaning trigger may vary depending on experience at the particular airport and conditions such as weather, crew member time, passenger disposition, airfield situation, fuel, and other resource availability (Turnbull, 2008).

The crew members should continue to have regular communication with passengers, the airline operations control center, and ATC to determine if takeoff is imminent, and to keep passengers informed to the fullest extent possible.

The deplaning trigger occurs when current events warrant deplaning, such as when the flight crew determines that a medical emergency exists, a number of passengers need to deplane, or the passengers can no longer be supported with adequate food, water, toilets, hygiene, or accurate information.

If passengers will be deplaned, the flight crew confirms the deplaning plan and, if needed, verifies that buses or other equipment and associated staff are available. Finally, the airline should coordinate with other aviation service providers such as airport operations, TSA, CBP, as applicable so as to prepare to get passengers off the plane if it is safe, necessary, and practicable to do so.

- Establishing Triggers

Triggers are specific events or points in time during a lengthy onboard ground delay when communication with involved stakeholders including passengers when appropriate is initiated, a decision is made, or an action is taken. Each airline has its own guidelines for establishing triggers. It is common for the triggers and the associated timelines to vary by airport, even within a single airline.

An airline’s internal guidance on trigger timelines should be consistent with its external commitments, both to passengers and to government agencies. Information on these commitments should be provided to airline employees, especially those who have the most direct contact with inconvenienced passengers (Grothaus, 2009).

At trigger points, airlines should consider a number of factors when making a determination. These include passenger disposition, including physical and emotional factors, national airspace system weather, crew member resource planning and legality, airfield situation and safety, gate availability, and hardstand availability.

- Including Triggers in the Contingency Plan

When developing a contingency plan, each airline should include its trigger policies, the threshold for each trigger, and what actions to take or decisions to make at the trigger time. It is vital for each airline to include responses that consider the needs of the passengers.

During a Lengthy Onboard Ground Delay

Different measures may be taken at different times as discussed in the following subsections.

Before Boarding at a Gate

If an airline anticipates that a flight may be subject to a lengthy onboard ground delay before boarding passengers, it should make a general announcement to inform the passengers about the possibility of a lengthy onboard ground delay.

This will enable passengers to take appropriate actions, such as determining whether they want to board or seek alternate transportation, cancel travel plans, or reschedule the trip as long as this is consistent with airline ticketing policies (Stambaugh, 2009).

If a passenger decides to board, this communication will help the passenger to manage his or her expectations and prepare for a possible lengthy onboard ground delay. It also gives the passenger the ability to communicate with others regarding the delay, obtain food and drink before boarding, or make other preflight arrangements.

Airlines should enable passengers to make informed decisions by providing them with information regarding the possible consequences of their decision to decline boarding (Kilkenny, 2006). Such consequences could include rebooking difficulties and change fees.

After Boarding Before an Aircraft Leaves a Gate

In the unusual situation where an airline anticipates a flight may be subject to a lengthy onboard ground delay with the flight’s scheduled arrival delayed after boarding passengers but before leaving the gate, the airline should inform the passengers about the possibility of a delay.

This will enable passengers to determine whether they want to remain onboard, deplane to obtain food and drink, seek alternate transportation, cancel travel plans, or reschedule the trip consistent inline with airline ticketing policies. This communication will help passengers to manage their expectations and prepare for a possible lengthy onboard ground delay (Price & Forrest, 2008).

Airlines should enable passengers to make informed decisions by providing them with information regarding the possible consequences of their decision to deplane. Passengers on a delayed airplane at the gate should receive flight status announcements no less frequently than every 30 minutes for the duration of the delay, even if there is no new information to report.

After an Aircraft Leaves a Gate

Airlines may consider establishing plans that include a series of triggers. This will help facilitate additional communication with passengers, coordination within the airline, and coordination with the airport and other aviation service providers during a lengthy onboard ground delay after an aircraft leaves a gate. Airlines should consider the following in its plans.

- In no event should a flight crew go more than 1 hour without company communications.

- Triggers should be determined by each airline based on time and the specific scenario and the airport service criteria

- Triggers may vary within and among airlines and should be tailored to accommodate operational variations.

- The airline should coordinate its triggers with the appropriate airport, TSA, and CBP personnel if international flights arriving in the United States are involved.

Keeping Passengers Informed and Meeting Passengers’ Basic Needs

During a lengthy onboard ground delay, the crew members should keep passengers informed to the fullest extent possible and make flight status announcements no less frequently than every 30 minutes for the duration of the delay, even if there is no new information to report (Elias, 2010).

Consistent with applicable Federal regulations and when practicable, the flight crew members should make refreshments and entertainment available, make every reasonable effort to ensure the lavatories remain serviceable, allow the use of communication and entertainment devices, allow passengers to stretch and move about the cabin.

Responding to Passengers’ Medical and Special Needs

The crew members should respond to passengers’ basic medical needs when alerted about a situation. They should ensure that the needs of any passengers with special needs are communicated to other relevant decision makers.

Plan for Deplaning During an Event

During a lengthy onboard ground delay, the airline should have procedures in place for deplaning passengers following predefined trigger events or circumstances. It is essential for airlines to coordinate with airports so as to identify an appropriate means of deplaning. However, deplaning options will be subject to the availability of facilities, equipment, and personnel at the airport.

Addressing the needs of passengers after deplaning at the conclusion of a lengthy onboard ground delay may involve the airline, the airport, government agencies, local lodging and transportation providers, and other aviation service providers.

The airline’s role may include arranging for onward transportation, providing compensation in line with airline policies, returning the passengers’ checked baggage, and directing passengers to local lodging.

Attending to Passenger Needs during the Event

This may involve meeting the needs when passengers are onboard the aircraft or when they are in the terminal.

Attending to Passenger Needs with Passengers Onboard the Aircraft

The airline should have procedures for ensuring that identified passenger needs are fully met during a lengthy onboard ground delay. The airline should also have procedures to ensure that it can address the needs of any passengers with special needs.

Attending to Passenger Needs with Passengers in the Terminal

When passengers in the terminal area are impacted during a ground delay, each airline, in coordination with the other aviation service providers as appropriate, should have procedures for responding to passenger needs, including those of passengers with special needs.

Conclusion

Generally, contingency planning involves more than a simple arrangement to recover from unexpected events (Gustin, 2010). Besides ensuring that an organization is well prepared to deal with any eventualities, a contingency plan will also see to it that the organization’s critical functions continue to be available even during disruptions.

A good contingency plan is therefore a very critical requirement for airport operations. The contingency planning strategy has several elements in common which include emergency response, recovery procedures, resumption of operations, implementation, testing and revision.

Reference List

Aviation Consumer Protection and Enforcement (ACPE)., 2008. Development of Contingency Plans for Lengthy Airline On-Board Ground Delays. Washington, DC: Aviation Consumer Protection and Enforcement. Web.

Balanko-Dickson, G., 2006. Tips and Traps for Writing an Effective Business Plan. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Professional.

Biggs, D. C., 2009. Guidebook for Conducting Airport User Surveys. Washington, DC: Transportation Research Board.

Bledsoe, B. E. & Benner, R. W., 2006. Critical Care Paramedic. New Jersey: Pearson Prentice Hall.

DIANE Publishing Company (DIANE)., 2004. Guidelines for Contingency Planning for Information Resources Services Resumption. Gaithersburg, MD: DIANE Publishing.

Elias, B., 2010. Federal Aviation Administration Reauthorization: An Overview of Legislative Action in the 111th Congress. Gaithersburg, MD: DIANE Publishing.

Florio, F. D., 2010. Airworthiness: An Introduction to Aircraft Certification. Burlington, MA: Elsevier.

Geering, W. A. & Amanfu, W., 2002. Preparation of Contagious Bovine Pleuropneumonia Contingency Plans. Rome, Italy: Food & Agriculture Org.

Grothaus, J. H., 2009. Guidebook for Managing Small Airports. Washington, DC: Transportation Research Board.

Gustin, J. F., 2010., Disaster and Recovery Planning: A Guide for Facility Managers. Lilburn, GA: The Fairmont Press, Inc.

Indonesian Contingency Plan Project Team (ICPPT)., n.d. Indonesia Air Traffic Services Contingency Plan Jakarta Fir – Part I. Jakarta, Indonesia: Indonesian Contingency Plan Project Team. Web.

Kazda, A. & Caves, R. E., 2007. Airport Design and Operation. Oxford, UK: Emerald Group Publishing.

Kilkenny, S., 2006. The Complete Guide to Successful Event Planning. United States: Atlantic Publishing Company.

Myers, K. N., 1996. Total Contingency Planning for Disasters: Managing Risk… Minimizing Loss… Ensuring Business Continuity. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley and Sons, Inc.

Pinal County (PC)., 2010. Special Events Emergency Contingency Plan Guide. Florence, AZ: Pinal County. Web.

Price, J. C. & Forrest, J. S., 2008. Practical Aviation Security: Predicting and Preventing Future Threats. Oxford, UK: Butterworth-Heinemann.

Riley, K. J. & Hoffman, B., 1995. Domestic Terrorism: A National Assessment of State and Local Preparedness. Santa Monica, CA; Rand Corporation.

Rothstein, P. J., 2007. Disaster Recovery Testing: Exercising Your Contingency Plan (2007 Edition). Quincy, MA: Rothstein Associates Inc.

Sharma, R.P., 2005. Industrial Security Management. New Delhi, India: New Age International.

Socha, T. M., 2002. Facility Integrated Contingency Planning: For Emergency Response and Planning. Lincoln, NE: iUniverse, Inc.

Stambaugh, H., 2009. An Airport Guide for Regional Emergency Planning for CBRNE Events. Washington, DC: Transportation Research Board.

Swanson, M., 2011. Contingency Planning Guide for Federal Information Systems. Gaithersburg, MD: DIANE Publishing.

Turnbull, K. F., 2008. Interagency-Aviation Industry Collaboration On Planning For Pandemic Outbreaks: Summary Of A Workshop, Part 3. Washington, DC: Transportation Research Board.

Virgin America (VA)., 2011. Virgin America Contingency Plan for Lengthy Tarmac Delays. Burlingame, CA: Virgin America. Web.