Introduction

Over the past decades, the use of controversial advertisements has been embedded into general marketing practices. The deliberate use of shocking or offensive imagery has aimed to attract the attention of consumers and increase their curiosity about the brand or a product that is being advertised.

The initial controversial advertising campaign is attributed to the United Colours of Benetton that pioneered provocative messages in their marketing. For instance, the brand released unrelated images depicting a black woman breastfeeding a white baby or a priest dressed in black, kissing a nun in white. The main objective of such photos was to raise awareness of the public about the diversity of colors, ethnicities, and cultures (Falk, 1997).

Empirical research has shown that controversial advertisements positively contribute to increasing the audience’s attention as their recall of the messages that are being transferred. Those campaigns that have been designed to provoke and shock usually result in the overall increased awareness, above and beyond information-based content. Nevertheless, it is necessary to discover whether consumers have a positive or negative attitude toward controversial ads.

While it is expected that slightly provocative content is better received than extremely provocative, it remains unclear whether there would be a positive impact on being attracted to the brand and wanting to purchase its product. Thus, the purpose of this paper is to study controversial advertisement outcomes within the ‘culture of affect’ through the case study approach.

Literature Review

The intention behind a controversial advertisement is to gain the attention of potential consumers, raise awareness of a brand or a product, and increase sales. Scholars have widely investigated the phenomenon of controversial ads due to their polarising nature as well as the capacity not only to shock but to bring attention to critical social issues. For instance, the campaigns by Benetton acquired great recognition for heightening public awareness of social problems but also have resulted in consumer campaigns and public outrage (Arnaud, Curtis and Waguespack, 2018). Calvin Klein campaigns, which allegedly included child images of pornographic nature, elicited boycotts and protests from the public.

Nevertheless, despite the fact that controversial ads can lead to adverse outcomes for brands, companies still use the strategy in the hopes to stand out against the media clutter and gain some attention, including the negative one (Erdogan, 2008). Such a perspective on the controversial advertisement has led to the increasing body of research on the overall influence of the approach as well as its effectiveness in the context of modern culture.

For example, Fam and Waller (2003) explored the influence of controversial products versus controversial advertising execution. The scholars determined six main reasons why consumers perceived marketing messages to be offensive. Such reasons included racist imagery, nudity, sexist undertones, the subject being too personal, indecent language, and anti-social behavior (Fam and Waller, 2003). Thus, there may be no dominant reason for advertisements being perceived as offensive as every consumer would have a different perspective on the topic that is being depicted. Although, it is notable that racist imagery has shown to be the most offensive while for women, sexist messages were rated second in the list.

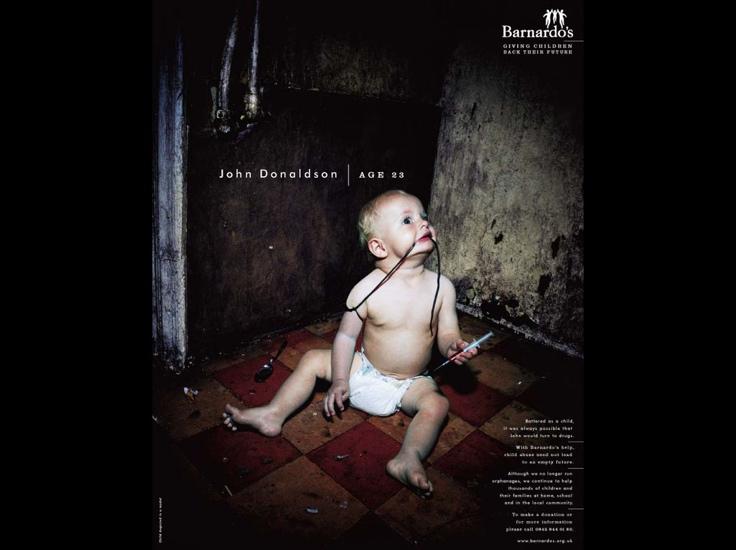

Scholars have also explored the impact of specific advertisement campaigns on the perceptions of the public. For instance, Ash (2008) investigated the influence of the campaign by the children’s charity Barnardo’s, which displayed charity children in public spectacles. While the objective of the provocative campaign, such as the Heroin Baby (see Figure 1) was to make the charity stand out from others and bring attention to pressing social issues, the advertisements were met with resistance and anger from the public. The uniqueness of Ash’s (2008) study related to the researcher drawing connections between provocative photography and the elicitation of shame among the target audiences. Controversial images, therefore, can shape the way the public perceives crises as well as the manner in which they are evaluated.

General beliefs and attitudes associated with controversial advertising are expected to affect the way in which consumers react to media. Beliefs refer to descriptive statements regarding the attributes of objects and may contribute to the development of particular attitudes (Wang, Doucet and Northcraft, 2006). Attitudes, in turn, represent a person’s internal and summative evaluation of an object and point to a stable and enduring predisposition to act in a certain way. As mentioned by Dens, De Pelsmacker and Janssens (2008), many consumers find controversial marketing socially acceptable and see it as entertaining.

This, in turn, increases their attitude toward a specific ad or a brand or product that it is promoting. The difference in the beliefs and attitudes toward controversial advertisements have also been shown to depend on culture. For instance, Chan, Li, Diehl and Terlutter (2007) compared the reactions of Chinese and German consumers to controversial advertisements. Chinese participants were found to be less accepting of offensive imagery compared to their German counterparts. Besides, Chan et al. (2007) revealed that the more unfavorable the perceptions of campaigns were, the higher was the likelihood of potential consumers rejecting the object that is being advertised.

The cultural context in which controversial advertisements are being inserted plays a significant part in the way the public is perceiving them. A recent study by Pires Trigo (2019) explored the differences in the way representatives of various cultures respond to controversial advertisements.

When being exposed to a controversial image, Europeans are less likely to have a negative response compared to the Asian group. While the first group will show some interest and curiosity in the advertisement to determine why such imagery was used, the Asian group is more likely to exhibit outrage with the message. Both groups were found to elicit an emotional response when being exposed to controversial images in an advertisement.

The culture of affect is a relevant aspect of the current discussion because it can point to the development of an emotional response to such phenomena as controversial advertisements. According to Holodynski and Friedlmeier (2012), the debate has been ongoing between the evolutionary and culture-relativistic approaches to explaining cultural differences and similarities in emotions. The impact of culture on emotional responses has shown to be prevalent as it would dictate the frequencies and types of emotional displays that are acceptable within particular cultures.

For instance, in Asian cultures, social harmony is given priority, while the Western perspective prioritizes the self-promotion of an individual. Furthermore, the expression of emotions varies depending on the context. While individuals from the United States can express negative feelings both in the presence of others and alone, Japanese individuals are more likely to do so only while alone.

As Westerners tend to be more open in the expressions of negative emotions, the phenomenon of outrage culture should be considered, especially in the context of social media domination. Outrage culture is closely related to the culture of effect and implies a form of public shaming aimed at holding individuals or groups for actions that are perceived to be offensive, inappropriate or controversial by other individuals or groups. Usually, displays of outrage occur on social media.

As mentioned by Shammans (2017) for the Huffington Post, democracy does not work in the absence of hard discussion, and uncomfortable dialogues are necessary to make society more cohesive, and thus, safer. Whether or not a controversial advertisement will be met by outrage is a matter of the topic being shown and its social significance. The outcomes of a marketing campaign that uses provocative messages will have an inevitable impact on the culture of affect and the overall response from the public.

Case Study Description

LUSH is a United Kingdom-based manufacturer of handmade cosmetics with stores around the world. In June 2018, the company released its #SpyCops campaign across its UK stores and produced several online articles explaining the issue that the company was pushing (see Figure 2).

The campaign focused on exposing “Spy Cops” or undercover police officers who infiltrated political groups to establish trusting relationships with them and collect data on subjects. There has also been some controversy regarding police officers having sexual relationships with campaigners from political groups while hiding the truth from their real families. In its essence, #SpyCops is a whistleblowing advertisement campaign to raise the awareness of public of the unethical police tactics and the devastation they would bring to their families.

The main problem with the campaign was that the majority of the general public perceived it as anti-police. There were reports of UK citizens complaining about the imagery and the message of the advertisement and being aggressive toward workers in stores, which, ironically, resulted in LUSH employees having to call the police (Belam. 2018). Because of the negative reception and the outrage from the general public, the company had to pull the advertisement and release an official statement.

The company mentioned that the campaign “was not about the real police work done by those front-line officers who support the public every day – it was about a controversial branch of political undercover policing that ran for many years before being exposed” (#SpyCops statement, 2018). Thus, the campaign was widely misunderstood by the public that saw the advertisement as an attack on the general integrity of UK police.

Discussion

The #SpyCops campaign release by LUSH is a perfect example of how outraged the public can become when the central message has been misinterpreted. Thus, when a new controversial advertisement is released, it is highly likely to be publicly shamed on popular online platforms such as Twitter or Facebook as well as online. The outrage culture aims to silence the controversial message, which often limits a constructive dialogue (Shammans, 2017).

Instead of having a constructive dialogue that LUSH was pursuing, the general public, with support from police, showed all possible signs of outrage and dissatisfaction, which ultimately led to the campaign being pulled. For instance, Ché Donald, the vice-chairman of the Police Federation of England and Wales, mentioned on Twitter that the campaign was “very poorly thought out” and “damaging to the overwhelmingly large majority of police who have nothing to do with this undercover inquiry” (Belam, 2018). Despite the fact that LUSH stressed that the company’s intentions were completely opposite, the public was still outraged.

The example of the campaign illustrates that controversy concerning social issues can have a deep impact on communities. With the wide availability of social media, those who opposed the advertisement were free to express their opinions about the wrongdoing of LUSH (Saner, 2018). Since there was a feeling that the company was criticizing the work of the police as a whole, the general public that had little information about Spy Cops and the actions of undercover officers, wanted to defend their law enforcement. It is important to note that the sales of LUSH during the campaign were 13% up, so the controversy associated with #SpyCops did some financial favor for the business.

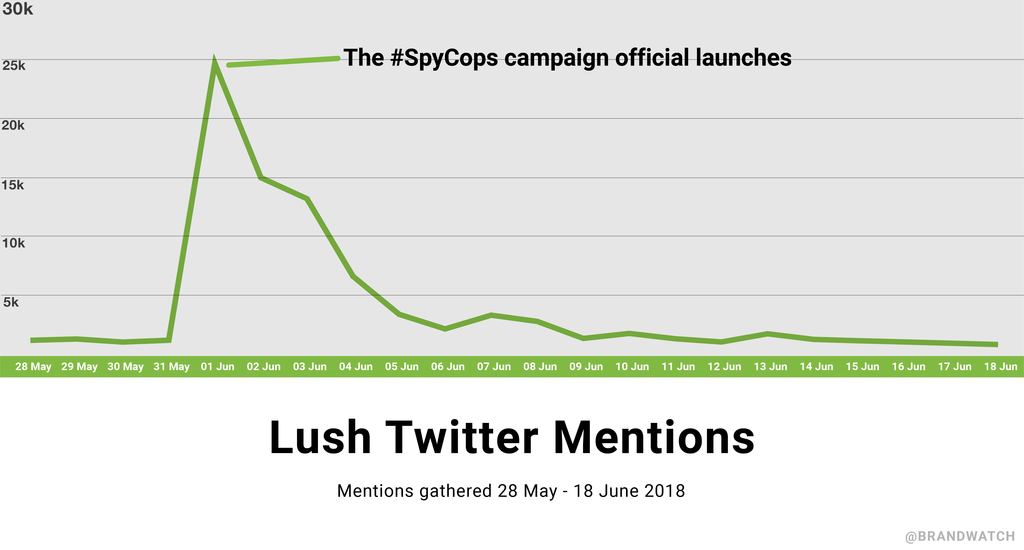

The Twitter campaign against the brand was severe, with LUSH mentions jumping 2321% compared to the previous week before the advertisement’s launch (see Figure 3). When there is significant outrage occurring on digital platforms, it is not long since the story is being discussed by politicians and traditional media.

The public backlash to the campaign was discussed in the Daily Mail, The Guardian, Telegraph, and the BBC. This shows the immense power that the ‘culture of affect’ has on public perception and influencing of the general narrative. To ensure the safety of their staff, LUSH had to outweigh the positive and negative consequences of its advertisement and shut the campaign altogether.

It is undeniable that the campaign brought attention to LUSH, both positive and negative. Potential customers who either supported or did not support the campaign used their power to share the controversial advertisement message with the calls to either boycott or support it (Kerr, Mortimer and Walle, 2012). The power of social media is highly relevant in this case because it facilitated the spreading of controversy and discussion among the general public.

The outrage, which predominantly occurred online, transformed into physical actions against LUSH employees. There were reports of shop workers being followed home, being verbally attacked, and cyber-bullied on social media. When the outrage that began online starts affecting individuals directly in their everyday lives, the constructive dialogue has been lost, with the ‘them versus us’ mentality being put at the forefront.

The discussion of the case can be concluded with the statement that those who held a generally positive attitude to the #SpyCops campaign and were aware of the unethical practices of undercover police offers showed their support and expressed their positive emotions. This has led to a more positive affective and cognitive perception of the advertisement, despite the fact that it was controversial (Arnaud et al., 2018). Individuals who are holding general negative beliefs toward the message that LUSH was communicating to its potential customers. This resulted in a negative affective and cognitive attitude toward #SpyCops.

The overall negative affective attitude was attributed to the overall misunderstanding of the campaign. Whether such a misunderstanding was intentional or not, it led to considerable publicity for the brand in the media overall. However, the culture of outrage did its job, and there was no other way for LUSH to save face than to abandon its campaign.

Looking through the comments on the post about the company’s campaign now, there are messages from customers who still support the way in which LUSH had handled the controversy. Although, there are also statements that point out that the campaign was not done correctly and could have been successful if there was a clear distinction between undercover police that are being targeted and regular law enforcement securing the streets and communities.

Conclusion

Controversial advertisements have been shown to spark public debate about the subject matter at hand. They are intended to shed light on issues that may be differently perceived by the general public. Depending on the attitudes of individuals toward a particular subject matter, a controversial advertisement campaign would elicit different responses in the general public. The cultural context also matters as representatives of some cultures are more likely to express their negative attitudes publicly.

The case study involving LUSH’s #SpyCops campaign is an example of how the outrage culture can bring negative publicity to a brand. In the age of social media, it is easy for the public to express their dissatisfaction with an advertisement due to the anonymity and safety offered by digital resources. However, the threats to LUSH’s workers crossed the line of safety, which made the company pull the campaign. Even though the message that LUSH was aiming to communicate was generally misunderstood, the case shows that negative publicity online would inevitably pressure the company to pull the campaign.

While #SpyCops did not include offensive images such as nudity, violence, or religious references, the depiction of a police officer undercover was triggering to the public. The work of law enforcement is seen as influential and respected, and people saw the advertisement as a direct attack on the profession intended to safeguard the safety of communities.

Reference List

Arnaud, A., Curtis, T. and Waguespack, B. (2018) ‘Controversial advertising and the role of beliefs, emotions and attitudes: the case of Spirit Airlines’, Marketing Management Journal, 28(2), pp. 108-126.

Ash, S. (2008) ‘“Heroin baby”: Barnardo’s, benevolence, and shame’, Journal of Communication Inquiry, 32(2), pp. 179-200.

Belam, M. (2018) ‘Cosmetics retailer LUSH criticized by police over ‘spy cops ad campaign’, The Guardian. Web.

Chan, K. W., Li, L., Diehl, S. and Terlutter, R. (2007) ‘Consumers’ response to offensive advertising: a cross-cultural study’, International Marketing Review, 24, pp. 606-628.

Dens, N., De Pelsmacker, P. and Janssens, W. (2008) ‘Exploring consumer reactions to incongruent mild disgust appeals’, Journal of Marketing Communications, 14(4), pp. 249-269.

Erdogan, B. Z. (2008) ‘Controversial advertising’, Journal of Marketing Communications, 14(4), pp. 247-248.

Falk, P. (1997) ‘The Benetton-Toscani effect: testing the limits of conventional advertising’, in Nave, M., Blake, A., MacRury, I. and Richards, B. (eds.) Buy this book: studies in advertising and consumption. London: Routledge, pp.64-83.

Fam, K. S. and Waller, D, (2009) ‘Addressing the advertising of controversial products in China: an empirical approach’, Journal of Business Ethics, 88(1), pp. 43-58.

Holodynski, M. and Friedlmeier, W. (2012) ‘Affect and culture’, in Valsiner, J. (ed.) The Oxford Handbook of Culture and Psychology. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 949-953.

Kerr, G., Mortimer, K. and Walle, D. (2012) ‘Buy, boycott or blog: exploring online consumer power to share, discuss and distribute controversial advertising messages’, European Journal of Marketing, 46(3-4), pp. 387-406.

Pires Trigo, A. (2019) ‘How different cultures respond to controversial advertisements: a three-way cross-cultural study’, University Institute of Lisbon. Web.

#SpyCops statement. (2018). Web.

Saner, E. (2018) ‘Interview: how the LUSH founders went from bath bombs to the spy cops row’, The Guardian. Web.

Shammas, M. (2017) ‘Outrage culture kills important conversation’, Huffington Post. Web.

Wang, L., Doucet, L. and Northcraft, G. (2006) ‘Culture, affect, and social influence in decision-making groups’, Research on Managing Groups and Teams, 9, pp. 147-172.