- Introduction

- Context

- Creative Industries in New Zealand

- Cultural policy and Well-being

- Cultural Policies of New Zealand

- Policies relating to Creative Industries in New Zealand

- Policies relating to National Heritage including Monuments and National Archives

- Policy Changes in New Zealand during the last Decades

- References

Introduction

Creative industries of New Zealand (NZ) have the potential to create not only knowledge but also goods and services in several fields. These include screen production, television, music, design, fashion, publishing, textiles and digital content. The creative industries have been built on the unique aspects of NZ’s culture.

These industries contribute to the economy of the country and they have become a vibrant feature in the international profile of the country. The potential of the creative industries extends to add to the productivity and contribute to the growth in other manufacturing areas as well as education.

The importance of the creative industries can be understood from the fact that the sector was responsible for providing jobs to more than 121,000 people at the time of 2006 census, which was 6.3% of the total employment and these industries have generated revenue of $ 10.5 billion in March 2006 (Andrews et al., 2009). The NZ government has formulated cultural policies and policies regulating the creative industries and these policies have been related to the well-being of the NZ people and the growth in the economy of the country.

There have been many changes in these policies relating to the creative industries. The objective of this portfolio is to make an in-depth study of the policies relating to creative industries in the NZ and to present a critical analysis of the policy development in this area during the last 10-15 years. This portfolio also focuses on analyzing the metadiscourse of sustainable development in relation to the creative industries in Aotearoa New Zealand.

The purpose of this portfolio is to present an analytical report on the policies of New Zealand relating to creative industries in the country. The portfolio is structured to have different sections dealing with policies relating to creative industries, policies relating to national heritage including monuments and national archives, policy changes in New Zealand during last decades and critical analysis of the policy developments relevant to the creative industries.

Context

In any country, the creative industries assume substantial cultural importance. With the present trend of increasing economic globalization, the magnitude of the importance of creative industries is progressively enhancing.

With the economic emphasis, moving towards the knowledge economy the existence and sustenance of creative industries have become crucial to the development of any nation as well as its economy. Creative industries have been identified to be a vital part of the economy of NZ, with the intrinsic value of the sector established beyond doubt.

In NZ, the creative industries occupy a prominent place because of their substantial influence on the economy and for increasing the growth opportunities in other industries. Since the government of NZ has made economic objectives as the backbone of the promotion of creative industries rather than the social and cultural objectives, this country differs extensively from other welfare economies in the world.

The policies of the NZ government with respect to creative industries consider “design” as an important element in the promotion of export and resultant economic progress. This uniqueness and the approach of the government in the promotion of creative industries make this study interesting and significant. The cultural policies of NZ and their implementation are also worth studying as the country has strategized its cultural priorities and objectives and the performance is measured against the preset goals.

Creative Industries in New Zealand

In the year 2002, the NZ government recognized the creative industries as a “leading potential contributor to [the] future economic growth and global positioning of the country” (de Bruin, 2005, p. 2). According to the NZ Heart of the Nation report, creative industries are “a range of commercially driven businesses whose primary resources are creativity and intellectual property and which are sustained through generating profits” (Heart of the Nation Working Group, 2002, p.5).

The definition of creative industries as acknowledged by the NZ government includes “advertising, software and computer services (including interactive leisure software), publishing, television and radio, film and video, architecture, design, designer fashion, music, performing arts and visual arts (arts, crafts, antiques) (New Zealand Institute of Economic Research, 2002).

The creative industries have been identified to be the key sectors for the economic transformation of NZ, since there is a huge potential of these industries for the economic growth of the country both in the domestic and global context. “The creative sector also includes niche industries which are not only vertically integrated entities, capable of standing as an economic industry on their own, but also horizontal enablers.

Horizontal enablers are apparent in industries with a basis in design,” (Beattie, 2009: P 9). Horizontal enablers are industries, which act to develop other industries through their contribution in any form. Other industries receive substantial support from the creative industries in the form of advertising, web design and new product development. The creative industries also help other industries through aiding in innovations and branding of the products (Smythe, 2005).

The economic, social and cultural values of a country are enhanced with the help of the activities in the creative industries. In other words, the creative industries have the potential to enhance these values (see e.g. Bilton, 2007; Santagata, 2005). A strong creative economy represents the creativity and dynamism of the country. The dynamism is reflected in all the industries and it indicates the strength of the creativity of the industries and their innovative capabilities (Bilton, 2007).

The NZ government has recognized the economic contribution of the creative industries and has been using the potential of the creative industries to cultivate and shape the national identity of the country, especially at a time when there are significant changes in the global economy. The government is investing in creative industries to boost the image of the country as an innovative, intellectual and creative country (Heart of the Nation Working Group, 2000).

NZ has used the creative industries extensively in both external and internal branding through campaigns like “PURE” launched by Tourism NZ and the Website “NZ Edge”. Painting of the images from the movie Lord of the Rings on the body of Air New Zealand aircrafts and the architectural design of the Rugby Ball Venue in Britain are some of the instances where NZ has been using the creative industries to highlight the uniqueness of the country.

Cultural policy and Well-being

The concept of well-being is closely associated with the transformation of places and economies affecting the lives of the people. Most of the Western countries have now taken on priority the agenda of notions of quality of life and the related concept of well-being and its sustainability.

Well-being is considered as the most desired outcome of the service delivery in mainstream activities. Similarly the concept of well-being takes the center-stage in the realms of education, healthcare, social services more specifically related to disabled and elderly citizens and it is evidenced by a number of different projects in public sector partnerships at all levels (Ager, 2002).

One of the main constituents of well-being is the culture and the quality of life and well-being is mingled with an emerging “therapeutic ethos” (Mirza, 2005). The cultural policy-making in the country of New Zealand is influenced largely by the notion of the increased role of culture in improving the well-being of the people (New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage, 2006).

The sustenance of well-being underpins the developments in cultural social indicators. In this context, the definition of ‘cultural well-being’ as adopted by the New Zealand government is worth noting. The definition goes as

“The vitality that communities and individuals enjoy through: participation in recreation, creative and cultural activities; and the freedom to retain, interpret and express their arts, history, heritage and traditions” (New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage, 2005, p.1).

In order to promote the cultural well- being of the people, Section 10 of the Local Government Act, 2002 enables the local governments to take actions to promote social, economic, environmental and cultural well-being of communities. Cultural well-being is considered as one of the four forms of well-being, which are interconnected with each other. The other forms are (i) economic, (ii) social, and (iii) environmental.

Specific instructions have been passed on to the local authorities in New Zealand to “integrate and balance these four types of well-being in planning and practice” (New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage, 2005, p.3). The provision contained in the Local Government Act, 2002 was influenced by the necessity to consider the well-being of the Maori community. “More recent migrants to New Zealand from the Pacific and from Asia are also seeking public acknowledgement of important cultural values.

A widespread acceptance in New Zealand has now emerged that culture is an essential component of individual and community well-being,” (Dalziel et al, 2006). From this point of view, there is deficiency in defining the cultural well-being objectives, as there is no statutory list of such objectives.

Cultural Policies of New Zealand

Creative New Zealand is a crown entity, which is established under the Arts Council of New Zealand Toi Aotearoa Act, 1994. The entity is made responsible for the development of arts in the country of NZ (Creative NZ). The function of the entity is to provide support to the professional artists and organizations promoting arts.

The entity extends the required support by organizing funding programmes. Creative NZ also provides special initiatives like audience and market development and assisting to form partnerships and in conducting research. The Arts Council governs the entity and other agencies including the Pacific Arts Committee that takes the funding decisions. The government through Vote Arts, culture and Heritage and the NZ Lottery Grants Board provides the major funding for Creative NZ.

There are four strategic priorities, which guide the work of Creative NZ. The strategic plan Te Mahere Rautaki 2007-2010 outlines these priorities, which are as follows:

- People of NZ are engaged in different arts.

- Superior quality NZ arts are promoted and developed.

- People of NZ are to have access to experiences in superior quality arts.

- Arts of NZ arts to gain international recognition and success.

The above priorities prescribe the focus for Creative NZ for the next three years of the planning period. The priorities outline the framework for planning and decision-making by Creative NZ in the matters relating to arts and culture.

The following table explains the objectives for each priority.

Source: Creative New Zealand (2007).

The strategic plan of Te Mahere Rautaki 2007-2010 represents a marked change in the focus from the previous cultural policies of the NZ government. The plan can be considered a significant improvement as it provides the framework for measuring the progress against preset goals and priorities in the areas of arts and culture and their promotion.

“The Strategic Plan 2007-2010, outlined in Part One, sets out the specific priorities and objectives Creative New Zealand is seeking to achieve or contribute to over the three-year period. Creative New Zealand has also developed a set of long-term outcomes that are expected to endure beyond the period of the plan. For each long-term outcome, a set of contributory outcomes have been identified” (Wahangr Aua Statement of Intent 2007-2010).

According to the Statement of Intent for Tauaki Whakamaunga atu 2008-2011, the entity of Creative NZ has “implemented an improved performance measurement framework,” (Creative New Zealand, 2008: P 20). This framework is likely to enable Creative NZ to demonstrate the ways in which its activities contribute to the strategic priorities and objectives against each priority and the relevant outcomes.

The framework has emphasized developing various measures “across the areas of quality, quantity, responsiveness and efficiency” (P 20). In addition to developing these measures, Creative NZ is working towards development of key indicators, which will “provide further information on trends internally or externally that may influence investment decisions and or the development of specific activities, programmes or strategies” (P 20).

Policies relating to Creative Industries in New Zealand

The creative industry strategy of NZ is relatively young and the Government’s Innovative Framework (GIF) formulated it. This entity was set up in the year 2001, which was meant to take care of the economic recession that hit the country few years prior to 2001.

During that period, the Ministry of Economic Development identified three strategic areas, which needed the support from the government for their development – biotech, InfoTech and creative industries. The government chose to work on the subareas of creative industries such as “screen production, games, publishing, music, fashion, textiles, furniture, digital media and design.” The government considered design as the “main enabler across the wider business community” (New Zealand Trade and Enterprise 2005: 1).

In NZ, the cultural and social dimensions of creative industries are not considered as part of the policies and strategies of the government. This is unique to NZ and it is a deviation from other welfare state countries. Therefore, the creative industries are promoted solely by innovation policies and economic policies.

In the year 2003, the NZ government undertook new policy measures on design and formulated a design policy. The government created an entity New Zealand Trade and Enterprise (NZTE), with the overall objective of creating a link between the designers and the innovation process in the business. The government released a grant of Euro 6 million for integrating design in to the innovative process during the planning period from 2003 to 2007.

The approach of NZ to creative industries takes an exclusive economic approach. The governmental agencies working with the creative industries such as the NZTE and the Growth and Innovation Framework are driven purely by economic objectives. The Ministry of Culture and Heritage has played relatively small role in the promotion of creative industries.

In NZ, the national economic development agency, New Zealand Trade and Enterprise integrate the activities of two other organizations Industry New Zealand and Trade New Zealand. The country employs exclusive economic arguments for promoting creative industries. The government views the creative industries from a more general perspective of innovation. In this context, the vision of NZTE states

“New Zealand will activate international excellence in creativity, design and innovations to radically re-position itself in global markets and value-chains” (New Zealand Trade and Enterprise 2005: 2).

The government has emphasized that the industry should be a part of the policy formulating process. This is evidenced by the statement that “the intention of the framework is for the private sector to shape the direction of the development of specific strategies” (Ministry of Economic Development, 2003: 21). In NZ, the economic potential of the creative industries has been taken to the area of export promotion.

The program “Better by Design” aims at improving the export performance of the companies in NZ through integrating design in the innovative processes in every type of business. According to NZTE, who initiates the program, the goal of the program is to achieve higher export revenue by making the products and services of New Zealand differentiate themselves by incorporating world-class design into them.

The government through the Better by Design program encourages the upcoming exporters by offering them

- free of cost advice on the implementation of design,

- funding to the extent of 50% of the cost of the design project subject to a maximum of $ 50,000 with the objective of building design capacity and

- education internships aimed at helping the businesses to get access to better skills available to work with then design capabilities of the company.

New Zealand is the only country, which has accommodated the use of design in its export promotion activities.

In NZ, the creative industries and culture are not financed by the tax expenditure, as in the case of UK or United States. However, the state acts as the facilitator in these two areas. The role of the state as the facilitator is explicit from the statement of the new plan for NZTE, which goes

“NZTE is a facilitator and a catalyst. We’re there to help make things happen. We don’t do the deals ourselves. They’re done by smart business people who are passionate about taking their ideas to international markets” (New Zealand Trade and Enterprise 2003: 3).

This statement shows that the policies supporting creative industries are solely aimed at correcting market failures instead of a whole framework to cover the entire activities of the creative industries. “It also shows that the NZ state has no intention that the promotion of creative industries should serve democratic, social or cultural goals” (Birch, 2008:96).

Policies relating to National Heritage including Monuments and National Archives

The government of NZ in accordance with its commitment, created a new Ministry for Culture and Heritage in the year 2000. The government provided NZ $ 80 million for the promotion of arts, culture and heritage sector with a programme for increasing the funds in the next three years.

The government considers the maintenance of the national archives and monuments as a significant part of its overall duties and ensures that the heritage values are considered, while various policy stances are taken. The government has adopted a best practice approach in order to

- “respect and acknowledge the importance of the historic heritage in its care;

- foster an appreciation of and pride in the nation’s heritage;

- ensure that its historic heritage is cared for and, where appropriate, used for the benefit of all New Zealanders;

- ensure consistency of practice between government departments;

- set an example to other owners of historic heritage, including local government, public institutions and the private sector;

- contribute to the conservation of a full range of places of historic heritage value;

- ensure that places of significance to Māori in its care are appropriately managed and conserved in a manner that respects mātauranga Māori and is consistent with the tikanga and kawa of the tangata whenua; and

- contribute to cultural tourism and economic development” (Ministry for Culture and Heritage, 2010).

The government has recognized that there are various constraints in managing the historic heritage. For example, there are the operational needs of specific departments like for arranging for the security of buildings under the custody of Department of Culture and Heritage and for arranging for the facilities to carry out research.

Similarly, the societal or cultural practices, which may have to changed to other places physically like the provision of facilities for immigrant groups may also pose significant problems in managing the heritage values. In addition, meeting the requirements of various statutes like the Building Act, 1991 needs striking a proper balance between different policy stances of the government. There are only limited resources with the government to meet the competing demands of this sector.

Under its policies to protect national heritage including monuments and national archives, the government has passed various legislations including

- Historic Places Act, 1993,

- Building Act, 1991,

- Reserves Act, 1977,

- Conservation Act, 1987 and

- Resource Management, Act, 1991.

The government has created the New Zealand Historic Places Trust (NZHPT), which is the leading national historic agency in NZ. The trust functions as the guardian of Aotearoa New Zealand’s national heritage. An Act of Parliament established the trust in the year 1954 and it became an autonomous Crown Entity under the Crown Entities Act, 2004.

The trust has the full support from the government and its functions are funded through Vote Arts, Culture and Heritage through the Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Historic Places Act, 1993 regulates the works, powers and functions of the NZHPT.

The government is reviewing the Historic Places Act and various other pieces of legislations to bring changes in the operation of the NZHPT and to revise the archaeological provisions in the Historical Places Act. The proposed changes include

- combining the two main types of archaeological authority to create one authority with a single administrative process

- reducing the statutory processing times for authorities from three months to 20 days (in most cases)

- ensuring the NZHPT’s Maori Heritage Council is involved in considering all applications that affect sites of Maori interest, and

- creating a new ‘simplified’ process for authorities of a more minor nature whereby the applicant is not required to provide an archaeological assessment with their application (New Zealand Historic Places Trust, 2010).

The objective of these proposed changes is to bring better alignment between the Historic Places Act and the Resources Management Act. There are various other proposals concerning the revamping the NZHPT under consideration of the government to ensure better protection to the historical places and monuments.

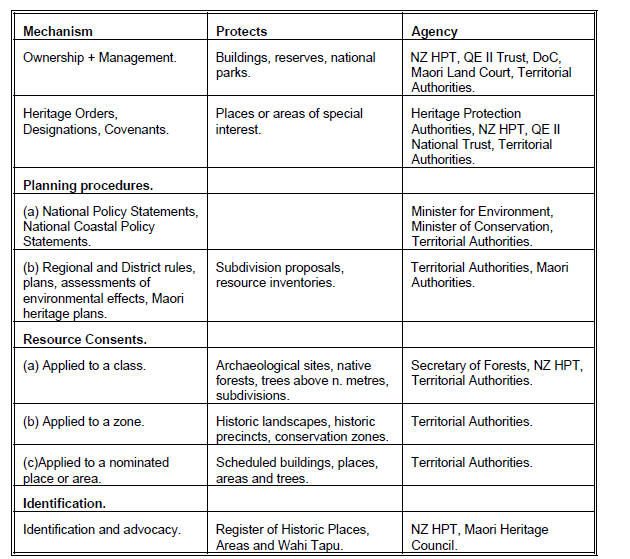

Thus, the framework for the protection of heritage sites and monuments in NZ is designed under various pieces of legislations like Conservation Act, Resource Management Act and the Historic Places Act. Various parliamentary Acts relating to the operation of territorial authorities also govern the management of historical places. The above table exhibits the major mechanisms available and the primary agencies responsible for ensuring the working of the mechanisms.

Even though there are various legislations govern the management of historical sites, a clear definition of the linkages among the major Acts has not been established which is a deficiency in the management of the historical places. However, the practices and policies of the agencies and institutions involved promote the integration in the activities.

“Functions at the two levels of government, central and local, are complemented by semi-governmental organisations such as the New Zealand Historic Places Trust and by non-governmental organisations such as Maori tribal authorities. It is common in colonial countries for the government to carry out functions that might elsewhere be the province of private organisations.

New Zealand has retained such structures longer than many countries and hence it has no private and fully independent national trust organisation but rather the NZ Historic Places Trust, which uncomfortably straddles the divide between being a government agency and a national trust,” (Allen, 1998:9).

The structure of organization and divide in carrying out the functions is another weakness observed in the management of historical places and national archives in NZ.

The government applied a moratorium on the further acquisition of properties by NZHPT in the year 1982. The Trust Board undertook a review of the properties in its possession in the year 1994 with the objective of rationalizing the Trust property portfolio. Based on this review, the Trust had to take decisions on the extent to which any Trust property would assist the Trust to meet its statutory obligations and such decisions were subjected to the available finances with the Trust.

However, the government has not provided any additional funds to the Trust in respect of this aspect of the work of the Trust. The Trust had to rely on a lottery grant for this purpose. The government announced a further 50% cut on the grants to the Trust, which severely constrained the property management work of the Trust.

It is to be noted that NZ’s system of local government and planning has more similarities with the systems followed in England. These similarities existed until such period the reforms were carried out in this area between 1988 and 1994 (Bush, 1995:1-81).

The planning for the protection of historical places and monuments has been taken in new directions with the new concepts introduced in the Resource Management Act, 1991 and the new organizational structure planned for the territorial local authorities by the Local Government Act, 1992.

However, there has not been a complete transformation of the systems in NZ in respect of the management of heritage sites and national archives. The agencies in the county have been endowed with the problems of resourcing and have been struggling to meet the ends. In addition, there are the problems of multiplicity of agencies, problems with assessment and nomination of places for scheduling and questions of preservation versus salvage excavation.

Policy Changes in New Zealand during the last Decades

The programme of comprehensive economic reforms in NZ was undertaken between the years 1984 and 1994. The reforms were undertaken in view of the recognition that the country did not achieve the same rate of economic growth as that of other OECD countries, since the country implemented economic policies that relied much on the regulatory controls.

Therefore, the successive governments have to undertake reforms in “monetary policy, fiscal policy, international trade policy, domestic industry policy, employment law policy, public sector policy and social security policy within a reasonably consistent framework intended to promote macroeconomic stability and microeconomic competition” (Dalziel et al, 2008:104).

Nevertheless, the decade of reforms witnessed considerable social dislocation and distress. Against the loss of social well-being the government introduced reforms aimed at promoting environmental well-being with the formation of the Ministry for the Environment and the passing of the Environment Act, 1986 (Young, 2007).

In the year 1991, the government passed the important legislation of the Resource Management Act, which can be considered significant for its recognition of the conjoint objectives for government policy.

This piece of legislation recognized the need for social, economic, cultural and environmental well-being. The inclusion of “cultural well-being” though unusual in international legislation can be understood with the recent history of New Zealand, which exhibits the pressure on the government to recognize the cultural treasures of Maori legally.

When the Labour-led government headed by Helen Clark took charge, the government announced the change of direction in the policies of the government (Dalziel et al., 2006).

The government acknowledged that the economic reforms undertaken during 1980s and 1990s were insufficient and there was the need for further economic transformation. The government also understood the need to sustain the national identity and culture and the two themes of economic transformation and promotion of national culture became the central focus of Clark’s government.

Critical Analysis of Policy Developments relevant to the Creative Industries

This portfolio argues that although NZ has made significant changes to its understanding of economic policy and cultural well-being over the last 15 years, there has been no interaction between the two policy frameworks. Combining economic policies with the cultural well-being may not produce the desired results as the use of cultural capital for economic well-being may damage cultural well-being.

It is essential that the cultural capital should be kept connected with the cultural context for promoting the cultural well-being of the country. This argument is supported by the following explanation on the tension between the policies of economic transformation and cultural well-being.

In order to analyze the incongruity between the policies, first there is the need to have an overview on the work of NZ Trade and Enterprise that strives to strengthen the creative industries as a mechanism for taking advantage of the culture of NZ to create economic wealth. This section also presents the examples of creation of intellectual property or a market brand out of cultural capital for an effective economic transformation and its real impact.

The economic reform of NZ can be considered to have ended with the passing of the Fiscal Responsibility Act in the year 1994. The governments after this period focused only on consolidating the economic reforms undertaken earlier but not extending any of them. The incoming government in 1999 concentrated on three projects – An innovation Framework for New Zealand, Catching the Knowledge Wave and Facilitating Economic Transformation – to achieve its objective of economic transformation.

The outcome of these three projects was “Growing an Innovative New Zealand” which led to the formation of “Growth and Innovation Framework (GIF). Based on this framework, the government decided to focus on creative industries among the three sectors selected by it.

The government initiated two task forces – one focusing on the screen production industry and the second focusing on design as the basis for promoting exports. It was the conclusion of the taskforce on screen production that creativity alone cannot lead the industry to grow. This was conveyed through a report produced in the year 2003.

The government formed New Zealand Trade and Enterprise (NZTE) in 2003, by merging the agencies responsible for trade promotion and industry policy with the objective of implementing national development policies.

NZTE positioned NZ as creative, innovative and technologically advanced under its “New Zealand New Thinking” objective, which aimed to drive economic transformation of the country based on the aspects of the history, heritage and culture. Based on these considerations and with the objective and focus of NZTE it emerges that the culture of NZ has become only a means to meet an end.

Culture has not been regarded as an objective having equal priority as the economic advancement. “The end in this context is economic well-being, with culture subsumed as a form of intellectual property that can be used to promote New Zealand exports, tourism, services and investment to global audiences,” (Dalziel et al., 2008: 111). It may be recalled that cultural well-being is one among the four well-beings projected by Section 10 the Local Government Act, 2002, which has not been given due consideration by the NZTE.

Based on the approach of NZTE and the government’s policy objectives, the future policy development is most likely to be guided by the following three major elements.

- “Cultural well-being requires access to resources, to fund support infrastructure for recreation, creative and cultural activities, to preserve history and heritage, to protect cultural freedom and to provide income opportunities to creative artists at the forefront of cultural development

- Recreation, creative and cultural activities make significant contributions to economic well-being by offering employment and income opportunities in industries such as screen production, fashion and cultural tourism

- Economic transformation can be enhanced by drawing on a country’s cultural assets to improve the design and marketing of its goods and services and to create a strong country brand for international trade and investment,” (Dalziel et al., 2008:115).

These points present a strong association and positive synergy between cultural well-being and economic transformation of NZ (Eames 2006). However, this portfolio argues that such association produces some tension, as there is likely to be significant overlap between economy and culture in areas like knowledge and cultural capital.

“It suggests considerable overlap between economy and culture in areas such as knowledge, social capital, cultural capital, customary rights, property rights, institutions and values. These areas of overlap are influenced by, and in turn influence, the economic and the cultural spheres” (Dalziel, 2008:115).This paper argues that while such overlaps may act to reinforce each other they bound to create tensions too.

One of the examples that can be cited in this respect is the use of traditional Maori design “koru” by Air New Zealand. The design “koru” symbolizes the Maori concept of how the life can change and can remain the same. Shand (2002:48) identifies koru as the central design feature of many of the artistic practices of Maori.

To add cultural image to its brand, Air New Zealand wanted to add the koru design to its carpets in the airport lounges. The Maoris objected to this idea saying that it is offensive to walk on their sacred symbol of life. The carpets were finally removed by the airline (Solomon, 2000: par 58; Shand 2002: P 51-51).

The symbol became the cultural capital of the country. Air NZ recognized the symbol as an economic advantage to increase its brand image. The cultural capital was protected in its original context, as customary right by the Maori people. When such cultural capital is considered as an economic opportunity in the Western market and legal system, the use of rights is treated in two different ways.

“First, the traditional use rights typically have no standing in the Western legal system, so that to those outside the culture, the cultural capital is effectively treated as a common resource; that is, a resource from which no one can be excluded. While there may be cultural sanctions against the misuse of a cultural treasure, and while there may be social implications from causing cultural offence, there is little legal protection.

Second, an outsider may seek to use the Western legal system to create a private ownership right using intellectual property law. As intellectual property, the original knowledge may become separated from its cultural context. It is possible for the original community to lose control over its own cultural capital; and people may become alienated from their own cultural artefacts,” (Dalziel et al., 2008: 116-117).

So long as the cultural capital remains in the form of a common resource, there is the risk of privatizing the resource. This is true because the ability to make use of knowledge with profit motive provides an incentive to privatise the cultural capital.

Another instance that substantiates the argument for showing the intersection between cultural well-being and economic policy can be seen from the points under the consideration of Waitangi Tribunal, which was formed to make recommendations on claims brought by the Maori people.

The point of contention by the Maoris include claims to protect knowledge concerning Maori arts, to protect against the exploitation and misappropriation of traditional artefacts, and carvings, to protect Maori intellectual and cultural property rights (as these were affected by the intellectual property legislation of NZ) and to protect the environment and natural resources. These points of contention were at the heart of the overlapping between cultural well-being and economic policy of NZ.

There is another example where there is a clash between economic objectives and cultural imperatives. NZ has accumulated substantial cultural capital in their national rugby team “All Blacks”. Even though this team was beaten in the quarterfinal match in the Rugby World Cup, 2007 the team could manage to create substantial commercial opportunities including the sponsorship from Adidas.

On the review by the New Zealand Rugby Football Union, it was pointed out that the All Blacks brand continued to be one of the successful brands and Adidas insisted that the team should continue their extraordinary winning record and ranking in the world rugby.

The review also pointed out that Adidas viewed this as a successful business relationship (Heron and Tricker, 2008: 38). However, the NZ Rugby Football Union is aware that the commercializing the All Blacks brand is likely to disturb its cultural affiliation. The union ensures that the team maintains its cultural roots intact. This might affect using the brand for economic gains in the future.

These examples clearly point out that use of cultural capital for achieving economic benefits is likely to impact the objective of cultural well-being if the cultural capital is not allowed to keep connection to its cultural context.

Critical Analysis of the Metadiscourse of Sustainable Development in relation to the Creative industries in Aotearoa New Zealand

“The complexity of discourse analysis presents a challenge to the researcher in respect of the limitations of the research. It is essential that the researcher have to take into account, the limitations of their own possibilities amidst the presence of a number of interconnections of every piece of the available text or discourse with lot of others” (Roggendorf, 2008).

According to Wodak (1996) “[…] every discourse is related to many others and can only be understood on the basis of others. The limitations of the research area therefore depend on a subjective decision by the researcher, and on the formulation of the questions guiding the research.” (p. 14)

This section outlines the premises that guided the concept of this portfolio and explains the data resources and the method followed for further analysis. As it may be observed, this portfolio used textually oriented discourse analysis.

It dealt with publicly available materials drawn from the electronic resources and government Websites apart from professional journals. The necessary information was retrieved from the recent experiences of New Zealand under its Growth and Innovation Framework, Local Government Act introduced in the year 2002 for examining the link between the economic policies and cultural well-being in the country.

The portfolio highlighted the manner by which economic transformation objective of the government has aimed at building up the part expected to be played by the creative industries in contributing to increase the economic advantage of the country with the changed policy objectives. The portfolio addressed changes in the policy stances of the government in making the cultural well-being a statutory objective of the local government and the way it has been made the responsibility of the local governments.

The portfolio based on few examples argued and highlighted the point that the necessity to use the cultural capital for sustained economic development may not lead to the desired results in increasing the cultural well-being of the country. It is essential that the cultural capital must maintain its association with its cultural context for ensuring cultural well-being of the people of NZ.

The portfolio also drew from the policies relating to historical places and from the works, functions and policies of the NZHPT. In the process of analyzing the policy framework relating to the protection of national monuments and archives including historical places, the portfolio highlighted the weak alignment among different legislations governing the protection of historical places and the problems and challenges faced by the agencies in maintaining sustained protection of the historical places.

This portfolio argues that since there is interdependence of the economic, environmental, social and cultural well-being, there is the necessity to formulate future policies that integrate the four well-beings together. The portfolio presents the point that such integration becomes essential in view of the fact that the policymakers use the cultural capital of the country to promote economic transformation.

This point is important for the future policy formulation to ensure sustained development of creative industries and to achieve the desired economic transformation since the current infrastructure for policy advice is not conducive for the integration of the well-beings, which are separate.

It is also important that the government have a thorough relook into the legislations governing the protection of the historical places, national monuments and national archives to attempt for possible integration among the statutes and to regulate the funding and functioning of the various agencies and institutions made responsible for looking after the important function of protecting the historical places.

In this area also, the present infrastructure for policy framework does not provide for a concerted effort by the associated agencies and they all struggle in the absence of proper coordination. After all, the government cannot neglect the protection of its national heritage and monuments.

References

Ager, A, 2002. ‘’Quality of Life’ Assessment in Critical Context’, Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, Vol. 15, No. 4, pp. 369-376.

Allen, Harry (1998) Protecting Historic Places in New Zealand. Web.

Andrews Grant, Yeabsley John and Higgs Peter L (2009) The creative sector in New Zealand: mapping and economic role: report to New Zealand Trade and Enterprise. New Zealand Institute of Economic Research. (Unpublished). Web.

Bilton, C. (2007). Management and creativity: From creative industries to creative management. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

Birch Sofie (2008) The Political Promotion of the Experience Economy and Creative Industries. Web.

Bush, G., 1995. Local Government and Politics in New Zealand. Auckland: Auckland University.

Comparison of Cultural Policy Models Umbrella Policy Framework: Comparison of Cultural Policy Models in Australia and Internationally. Web.

Creative New Zealand (2007) Strategic Plan and Statement of Intent Retrieved. Web.

Creative New Zealand (2008) Statement of Intent. Web.

Dalziel Paul, Matunga Hirini, & Saunders Caroline., (2006) Cultural Well-being and Local Government: Lessons from New Zealand Australian Journal of Regional Studies 12 (3) pp 267- 280.

Dalziel Paul, Matunga Hirini, & Saunders Caroline., (2008) Economic Policy and Cultural Well-being: The New Zealand Experience Proceedings of 32nd ANZRSAI Conference. pp 103-123.

De Bruin, A. (2005). Entrepreneurship in the creative industries: The New Zealand experience (Working Paper 05.04). Auckland, New Zealand: Massey University, Department of Commerce.

Eames, P. (2006b) Cultural Well-Being and Cultural Capital. PSE Consultancy: Waikanae.

Heart of the Nation Working Group. (2000). The heart of the nation: A cultural strategy for Aotearoa New Zealand. Web.

Heron and D. Tricker (2008) Independent Review of the 2007 Rugby World Cup Campaign. Wellington: New Zealand Rugby Union. Web.

Ministry for Culture and Heritage (2010) Policy for Government departments’ management of historic heritage 2004. Web.

Ministry of Economic Development (2003) Response to GIF Taskforce: Overview Paper Office of the Ministry of Economic Development.

Mirza, M., 2005. The therapeutic state. Addressing the emotional needs of the citizen through the arts. International Journal of Cultural Policy 11(3): 261-273.

New Zealand Historic Places Trust, (2010) Review of the Historic Places Act 1993. Web.

New Zealand Institute of Economic Research, (2002). The creative industries in New Zealand: Economic contribution. Web.

New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage (2005) Cultural Well-Being and Local Government. Report 1: Definitions and Contexts of Cultural Well-Being. New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Web.

New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage (2006) Cultural well-being and local government. Report 1: Definitions and contexts of cultural well-being, New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Web.

New Zealand Trade and Enterprise (2003) Strategic Plan New Zealand Trade and Enterprise July 2003 Success by Design.

New Zealand Trade and Enterprise (2005) Creative Sector Engagement Strategy New Zealand Trade and Enterprise.

Roggendorf (2008) How New Zealand Universities Present Themselves to the Public: An Analysis of Communication Strategies. Web.

Santagata, W. (2005). Creativity, fashion and market behaviour. In D. Power & A. J. Scott (Eds.), Cultural industries and the production of culture, (pp. 75-90). New York: Routledge.

Shand, P. (2002) Scenes from the Colonial Catwalk: Cultural Appropriation, Intellectual Property Rights and Fashion. Cultural Analysis, 3, pp. 47-88.

Smythe, M. (2005). The creative continuum chapter seven: Going global. Web.

Solomon, M. (2000) Strengthening Traditional Knowledge Systems and Customary Law. Paper prepared for the UNCTAD Expert Meeting on Systems and National Experiences for Protecting Traditional Knowledge, Innovations and Practices, Geneva.

Wahangr Aua Statement of Intent 2007-2010 Part Two Page 20. Web.

Wodak, R. (1996). Disorders of discourse. London/New York: Longman.

Young, D. (2007) Keeper of the Long View: Sustainability and the PCE. Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment: Wellington.