Introduction

In healthcare, policies and procedures refer to the general guidelines and specific ways in which the administration of medical delivery is undertaken. It refers to the proper means of doing clinical duties in hospitals and other related institutions. Through policies and procedures, consistency in healthcare practice is promoted, and mistakes are reduced and patients and employees are kept safe. Healthcare policies and procedures cover aspects such as patient care, workplace safety, information and data privacy security, and administrative and human resource functions, leading to operational efficacy and limitation of liabilities in clinical practice.

Policies and Procedures

Patient Care

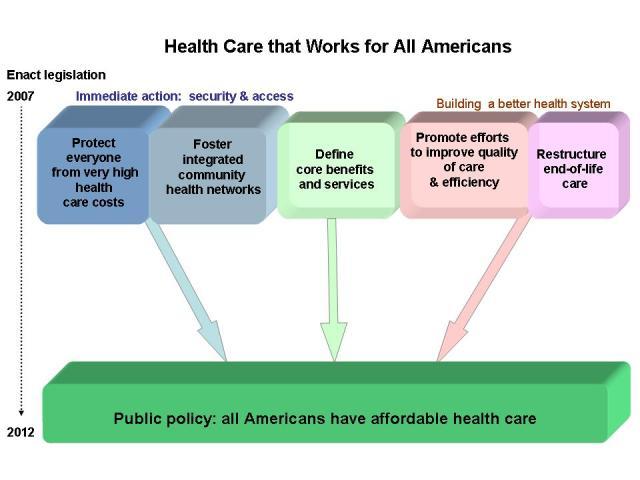

The key goal of providing healthcare is to ensure patients recover from their illnesses. Therefore, delivering clinical services to patients requires set guidelines and procedures to ensure efficiency and success. This means specific aspects will be covered, such as nutrition guides, patient family education, the rights of patients, and any abuse or neglect during admission or discharge at a care facility, among others (Paul & Kulshreshtha, 2020). Depending on eligibility, healthcare organizations liberate insurance options such as Medicare and Medicaid plans. That means hospitals may engage in contracts with these programs, making it easy for the patient to get enrolled based on their affordability, as seen in Figure 1.

Under patient care, medication is a critical factor that must be checked to ensure no individual or group liabilities. Healthcare service providers must promote accountable approaches in handling medicines to ensure integrity in the administration and supply of medicine. There are records on how patients have been prescribed to take their medicine; the key goal is avoiding the risk of erroneous medication, misuse of medicine, or theft (Saeki et al., 2023). That means the medication is prescribed and maintained in a particular manner whereby patients receive the correct and relevant medicinal approach guided by hospitals’ procedures.

Workplace Health and Safety

When working, staff must align to various procedures that benefit everyone around the medical environment as far as workplace health and safety is concerned. Employees must be covered to offer exemplary medical services to clients. For example, in critical care, safety options include staff being required to have personal protective equipment (PPE) that bars them from underlying risks (Paul & Kulshreshtha, 2020). The procedures include mandatory wear of face masks, hand gloves, medical glasses, protective boots, and an overall if one works in a risky area within a hospital facility such as Coronavirus-diagnosed patients’ wards. Under workplace safety, it is recommended that the staff limit their exposure to substances that may have chemical reactions to their bodies or equipment that may affect their health (Mondal, 2019). For instance, doctors working with X-ray equipment must be careful to avoid exposure to radiation while undertaking a patient scan.

Security of Information and Data Privacy

Nurses and doctors get confidential data and information that must be kept anonymous when working in healthcare facilities. Patient details should not be exposed to third parties to avoid segregation, stigma, or exploitation based on what a person is suffering from. Additionally, due to the high usage of tech in medical provision, care facilities have been vulnerable to cybercrime activities where malicious persons access systems virtually to steal important data or money. There is an existing policy known as the Health Insurance Portability and accountability act (HIPAA) that requires the creation of universal standards that protect sensitive information about a patient (Mondal, 2019). Healthcare organizations must be aware of that policy to ensure they remain relevant regarding data and security breaches. The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act provides security options on how information can be made anonymous. Failure to comply with HIPAA may cost a facility a minimum of $1.5 million per year on a single incident (Paul & Kulshreshtha, 2020). These protective procedures are important to ensure that patient data cannot be tampered with due to weak systems in place for a healthcare facility.

Administrative and Human Resource Functions

Another category of healthcare policies and procedures includes administrative and human resource (HR) perspectives. That covers all the aspects of running a medical center, from a business to personal paraphernalia. When caring for patients, the top leaders need to know they are still a business and must have an effective flow of operations to meet the objectives and get sufficient returns. Additionally, policies and procedures under this category require HR to address various issues such as dress code, off days, shifts, and general conduct while one is at work (Mondal, 2019). For example, many hospitals require an employee to be at their workstation for fifteen minutes to get a comprehensive handover of what is happening as they start their shifts (Mondal, 2019). Thus, administrative and HR policies and procedures are key to ensuring efficacy in functional aspects of the workforce. Under this policy, supplies are monitored to ensure there is no shortage of drugs at any given time. In this case, vendors are encouraged to offer material and drug requisitions through procurement. That enables transparency and leads to sustainable clinical practice.

Similarities and Differences

Medical policies and procedures have various perspectives that make them similar and different. The first similarity of these policies and procedures is that they all have a holistic approach to keeping patients and healthcare workers safe from risks and liabilities. For example, patient care policies benefit hospitalized individuals, while workplace safety covers the well-being of employees (Mondal, 2019). The other similarity is that they are integrated into a legislative realm whereby failure to honor the policy or procedure may result in legal punishment. For example, a facility that does not protect its data can give hackers an easy time accessing data or resources. Therefore, patients can sue the facility, whereby the management and staff on duty can be arraigned in court and charged with breach of data privacy.

Similarly, failure to manage employees effectively can lead to irresponsibility, which can cause fines that are enforced legally. That means these procedures and policies have a legal ground of action if one does not follow them. The other similarity is that they affect coordination and how healthcare organizations offer clinical practice (Paul & Kulshreshtha, 2020). For example, the guidelines on conducting surgery or operating equipment make it easy to achieve desired results in care. Additionally, having specific measures concerning employees and patients assures success in administering medical services. Therefore, these policies and procedures complement each other when undertaking clinical duties.

The differences can be evident depending on the category of policy and procedures. The first difference is that they require different personnel to make a course of action to ensure the clinical practice is moving correctly. That means some require administration while others need staff to act, and patients must also play. For example, patient care and data privacy are decisions made by healthcare workers on the ground who deal with patients from a personal level. On the other hand, workplace safety and administration and HR require healthcare leadership to see the medical practice’s success (Mondal, 2019). Lastly, these policies and procedures do not have a uniform approach since any lapse can result from unavoidable circumstances. For example, a security breach can result from technical hitches that may alter the normal functions of the software to bar cybercrime crew from accessing important utilities. Additionally, patient care can be limited by the lack of coordination from the patient, where a nurse does not have the power to control an individual.

Medical Policies and Procedure Limitation of Liabilities

Enhanced integration of medical procedures and policies limits personal or group liabilities. When a care facility sets standards for patient care, the key goal is to avoid violating patient rights that may lead to legal actions. Thus, following patient care policies and procedures limits healthcare workers from being accused of negligence during care. A hospital accused of frequent breaches of policies and procedures has an adverse clinical practice reputation that may lead to sabotage of operations, hence, a lack of job sustainability (Mondal, 2019). Compliance with insurance options makes it easy for a healthcare firm to offer the required medication, which can be reimbursed through an individual’s coverage. Therefore, consistent adherence to policies and procedures prevents high rates of mortalities or increased exacerbations to patients, which makes a working environment poor.

Existing policies and procedures allow the establishment of standards of care that limit legal actions. For example, if a healthcare firm is critical to protecting its systems well, there would be no data breach due to negligence; hence, any penalties, fines, or legal sanctions will not be experienced. Furthermore, they prevent punitive measures such as incarceration for employees found guilty of violating policies and healthcare standards (Paul & Kulshreshtha, 2020). For example, a person working in high dependency units (HDU) follows safety procedures that make them and the patient under care safe. Strict adherence to the guidelines protects them from getting harmed or leading to the patient’s death, an act that can be pursued under criminal law, and the worker is put behind bars.

Lastly, policies and procedures prevent a healthcare firm from experiencing financial constraints. The reason is that following the required standards of care makes it easy for medical officers to perform all the functions, including charges for treatment (Saeki et al., 2023). When a hospital is challenged to follow the policies, it loses clients and is forced to retrench workers, citing financial struggles. It becomes unfortunate for a person to lose their job due to monetary issues a firm is experiencing as a result of failing to adhere to set guidelines in the workplace. Therefore, policies and procedures are meant to prevent these predicaments in medical delivery.

Impacts of Policies and Procedures in General Administration of Medical Practice

It is important to have set guidelines on the provision of healthcare. The impacts of policies and procedures in general administration comprise the efficacy of operations, safety at the workplace, high productivity and output, commendable revenue returns, and low staff turnover, which means stable and consistent employee functions. A well-aligned procedure in undertaking medical practice improves communication which is key in operations (Paul & Kulshreshtha, 2020). For example, a nurse is guided by a doctor to perform specific functions meant for a patient’s welfare, following standards of care practice. That means they do not make decisions independently but based on the procedures set.

The safety factor is evident when nurses and doctors can prevent mistakes that can put their lives and that of the patient in danger. For instance, operation equipment used for scanning purposes requires a high level of expertise since intensive radiation can harm any person. A person with this knowledge will act rationally regarding the equipment’s operational aspect (Saeki et al., 2023). Lastly, policies and procedures reduce liabilities in healthcare firms, meaning staff will stick in their working stations and not resign or seek other employers. All these impacts show the importance of adhering to medical policies and procedures.

Conclusion

Healthcare policies and procedures are critical in medical practice. These policies and procedures include standards of operations in patient care, workplace health and safety, information and data privacy security, and administrative and HR functions. These policies and procedures are similar since they aim at the safety and well-being of patients and employees. The other similarity is that they have legal aspects behind them that keep them relevant in clinical practice. The difference is felt in decision-making and inconsistent approach to execution. The standards of care limit liabilities by preventing mortalities and legal sanctions. Impacts include patient safety, efficacy in clinical operations, and low staff turnover.

References

Mondal, R. (2019). Medical ethics and policies related to biomedical equipment. Biomedical Engineering and Its Applications in Healthcare, 4(6), 733–738. Web.

Paul, S., & Kulshreshtha, S. K. (2020). Global developments in healthcare and medical tourism. IGI Global.

Saeki, S., Okada, R., & Shane, P. Y. (2023). Medical education during the COVID-19: A review of guidelines and policies adopted during the 2020 pandemic. Healthcare, 11(6), 67–78. Web.