Mental health has always been a major subject discussed across all types of media. The historical representation of mental health conditions, however, was, and sometimes still is, not positive. The history of television programs, newspapers, and magazines reporting the stories of people with anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa, the two most recognized eating disorders (EDs), shows a pattern of stigmatization and hopelessness.

Currently, these interpretations seem to be changing, thus making one think that the conversation is shifting more towards helping, rather than castigating, people with EDs. Representations, through personal stories, are growing, with more and more individuals sharing their journey towards recovery.

Apart from traditional media, modern society is highly engaged in social media. As such, platforms including Tumblr, Twitter, and Instagram can be perceived as valuable contributors to the discussion of EDs.

The ideas shared on these sites vary as well, but their influence on users is substantial. One can argue that traditional media, through the depiction of ED stories, started the discussion about mental health, introducing concepts of anorexia, bulimia, and other conditions, often described in a negative light due to the need for their portrayal to be dramatic. Social media, then, invites people to continue talking about these notions, interpreting the information shown in programs and magazines, and often reversing its message. As a result, pro-ED sentiments arise, and whole communities form around harmful ideas.

The correlation between the depiction of EDs and pro-ED sentiments can be reviewed through the example of the news report of Lady Gaga’s anorexia and bulimia, published by many major publications in 2012. Since the singer has a significant influence on her audience, as well as the general public, her story became a significant contributor to the general conversation about mental health.

This present paper aims to evaluate how such news, and their associated narrative, is treated by the mass media, including magazines, social media posts, and the public reactions of other celebrities and the general population. It is possible to argue that programs in traditional media still apply some degree of stigmatization in their ED-related publications, and their ineffectiveness is seen in social media responses where people escalate the discussion.

The History of Mental Health Representation

To understand why the discussion of mental health and EDs is seen as changing, one has to look at the material that has been published previously. The analysis of papers from 2008 to 2014 in England by Rhydderch et al. (2016), for instance, reveals that the stories in printed publications have changed significantly over the years. While the authors take a seemingly short period, six years, their conclusions show a substantial shift from one type of discourse to another within that time.

The amount of anti-stigmatizing materials grew, although the amount of negative information continued to increase as well. In 2014, the number of stigmatizing articles accounted for more than 40%, while reaffirming and supportive depictions were only recorded in approximately 30% of all texts (Rhydderch et al., 2016). The authors also found that hopelessness was among the central themes linked to EDs throughout the whole timeframe. Thus, one may see that the overall tone of articles in previous years was more negative.

It is also vital to ask what information such a negative portrayal may contain. People with mental health illnesses are routinely perceived as a danger to society and themselves, a hopeless victim, or the only person responsible for their mental health problems (Holmes, 2018). Here, the idea of victimhood arises as one of the major themes in ED portrayal – anorexia and bulimia are linked to people’s inability to analyze the information that is presented to them adequately.

How Traditional Media Starts the Discussion

Currently, the subject of EDs is often discussed in shows, newspapers, magazines, and other media sources. This rising interest in mental health has prompted authors to portray more stories that are based on real-life examples. Nevertheless, this does not mean that these depictions are now devoid of the issues that plagued older publications. The infantilization of women and young girls prevails as one of the most stigmatizing descriptions of these disorders (Holmes, 2018).

Holmes (2018) notes that the blame for the development of anorexia and similar disorders is often attributed to young girls who are thought to be easily affected by mass media. The narrative that many articles pursue is that girls are impacted by the images of a perfect body, and they subject themselves to starvation and other harmful practices due to their inability to separate media images from reality. The concepts of thinness, beauty, and food consumption are portrayed at the center of the problem.

Apart from presenting information about EDs through the lens of victimhood and personal responsibility, publications also often tackle celebrities’ revelations about their previous history of an ED. Here, magazines and programs make similar mistakes in seemingly glamorizing or dramatizing the narrative, thus failing to portray EDs as unhealthy and undesirable. According to Yom-Tov and Boyd (2014), a direct link exists between the coverage of information about celebrities who are perceived as anorexic and the public’s interest in searching websites related to anorexia and weight loss. Therefore, by seeing or hearing about underweight singers and actors or actresses, people are more inclined to look up resources for weight loss.

In the last few years, various celebrities have shared their path to recovery from an ED, including Lady Gaga and Demi Lovato. In the case of Lady Gaga, however, the response of the public was divided. While some people used this information as inspiration for their recovery or as an awareness-raising strategy, others ignored the originally intended message of healthiness, and instead praised her struggles with weight loss.

Here, the influence of the portrayal of traditional media can be reviewed based on a real-life example. Lewis, Klauninger, and Marcincinova (2016) collected data from Google Trends following the news about Lady Gaga to investigate whether the number of anorexia and bulimia-related searches had increased. The scholars found that in one month after the news was released in major publications, the number of Google entries with pro-ED words rose by 30% on average (Lewis et al., 2016, p. 2). Moreover, the interest in “pro-ana” websites (sites that depict anorexia in a positive light) increased drastically.

The majority of publications shared photos of Lady Gaga taken during her struggle with anorexia. They were published by the singer herself as she wanted to “[take] a stand for a positive body image by starting a body revolution” (Greenwald, 2012). Looking at this, one may note a positive and anti-stigmatizing approach to discussing the disorder. These photos were then used in communities in other contexts, as “thinspiration” – the use of pictures of thin people as an inspiration for extreme weight loss. This is where social media enters the discussion as a platform that is largely based on reacting to other content.

How Social Media Escalates the Discussion

While traditional media sources deliver a large part of all information to the public, they do not foster the same response rate and speed as social media posts. The role of social media websites and applications (Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, Tumblr, and others) can be considered even more influential in promoting “pro-ana” and “pro-mia” (positive depictions of bulimia) tendencies. An analysis of social media posts reveals several characteristics of online ED discussions.

First, some studies show that the portrayal of EDs on social media is glamorized. Achievement of body standards, even those that many users in pro-ED communities establish are extreme, are portrayed as vital for one’s happiness. This representation is not unique; similar depictions are present throughout the mass media within general advertising and the fashion industry. However, the lengths to which the proponents of EDs will go are targeted at creating an exaggerated type of such an ideal.

Social media conversation is different from that of mass media publications and programs because it opens a dialogue between people with similar views and goals. Those who share information about weight loss, especially if it is done through harmful means, are more inclined to believe blogs and individuals rather than more traditional sources, such as women’s magazines (Holmes, 2018). One can also use this finding to discuss the role of mass media in forming and supporting the idea that such publications are bad or untrustworthy.

On the other hand, blog posts discussing similar issues written by people are deemed more realistic and trustworthy in the depiction of EDs. This comparison can be both useful and harmful, depending on the contents of such magazines and blogs.

Returning to the idea that social media offers anyone the opportunity to converse with others, one can show how pro-ED sentiments are spread. A simple search for weight loss, exercise, and dieting can turn into a post about “thinspiration,” and escalate into a variety of pro-ED concepts. Scholars also perceive there to be a connection between EDs and other mental health problems such as depression. Pater, Haimson, Andalibi, and Mynatt (2016) find that the use of hashtags is a link between these issues – a person searching for a particular idea may become connected to other concepts. Thus, the positive portrayal of EDs may start as a subtle comment about one’s appearance, such as general unhappiness with weight or form, but, then, can escalate into a harsher comment about oneself stemming from reading pro-EDs sentiments.

Another difference between the portrayals of EDs in different media sources is the presence of mutual support in social media circles. While publications and programs may portray EDs as dangerous and negative, they cannot actively offer advice to people with eating problems. On the other hand, such platforms as Tumblr and Twitter were created to unite people based on their interests. As a result, whole pro-ED communities can uphold the positive image of EDs and offer mutual support for their members, thus limiting the effectiveness of interventions. Pater et al. (2016) describe these groups as networks where people share information and use specific images and concepts to further pro-ED ideology.

A real-life example is the use of specific hashtags on social media and the effort of these platforms to restrict dangerous ED conversations. People interested in losing weight share their troubles. Others then respond with similar stories, encouraging the author of the original post not to give up. In contrast to a more thoughtful mass media presentation, where recovery is linked to health and happiness, these communities construct a narrative that a thin body is an ultimate goal. The path of EDs, here, is portrayed as strategic, since it is the only way to achieve beauty, self-confidence, love, and recognition.

This is one of the portrayals of ED, although it is not always shared by all people with the disorder. Pater et al. (2016) provide several hashtags that are shared as positive encouragement, for example, “thinspiration, bone aspiration, promiainspo” among others. As one can see, the idea of thinness is portrayed as positive and desirable. The term “bone aspiration” and its derivatives, in particular, show the extent of the aspirations such communities establish. This hashtag is often accompanied by pictures of people with visible bones.

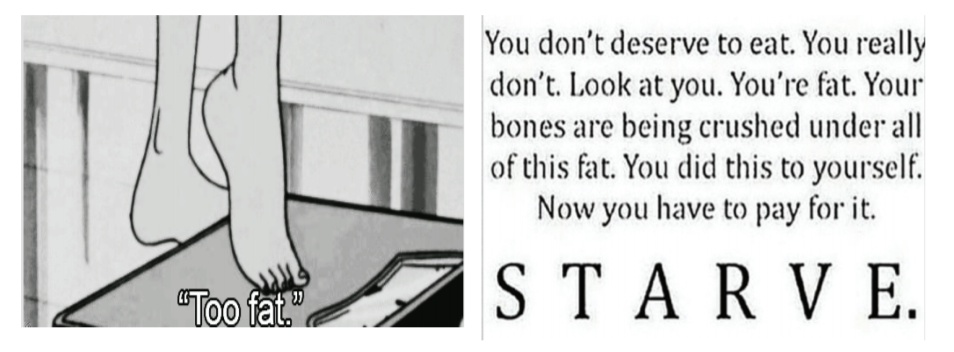

Apart from mutual support, the pro-ED portrayal is also rooted in the notion of self-mutilation and self-hatred as being inseparable from goal achievement. Pater et al. (2016) provide examples where “thinspiration” is not based on pictures of skinny people but, rather, on activities that will lead to that goal. As shown in Figure 1, sentiments such as “you do not deserve to eat” and “your bones are being crushed under this fat” are utilized (Pater et al., 2016, p. 1192). These and similar posts are, however, not regarded as insulting, but as inspirational and moving. Food consumption is seen as an indulgence of personal weaknesses rather than a biological need. Eating disorders, on the other hand, are seen as a part of one’s identity, a tool for goal achievement, and a positive personality trait (Pater et al., 2016).

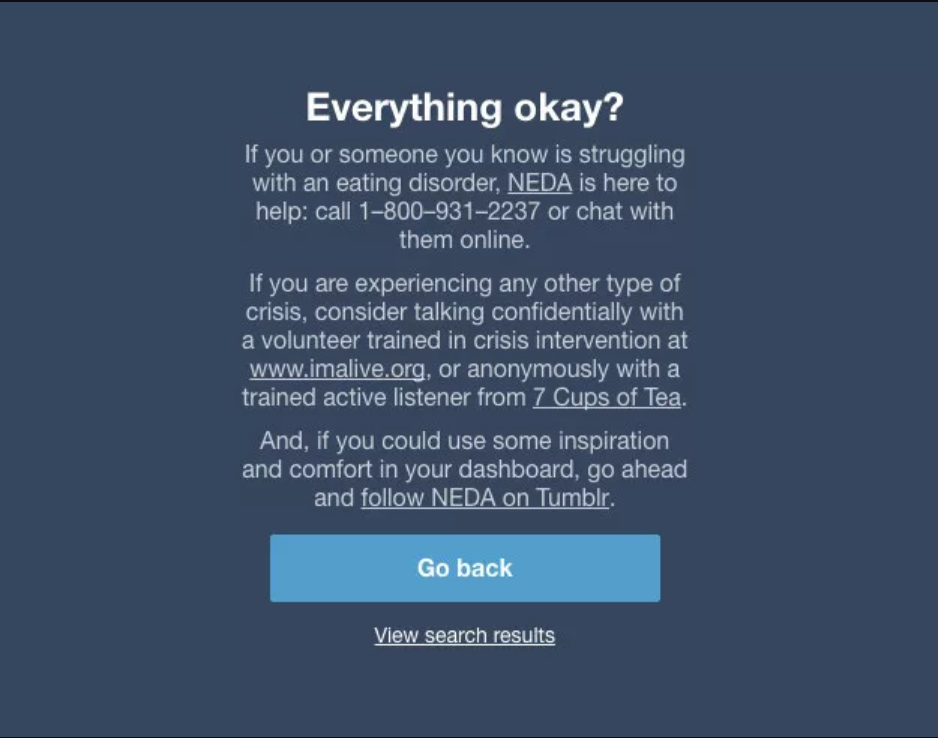

This positive view of EDs is difficult to overcome, and platforms that try to restrict such portrayals are met with many obstacles. The widespread interest in pro-ED ideas has caused social media platforms to introduce filters and restrictions to their sites. Currently, Tumblr and Instagram oversee several common hashtags related to EDs, including “anorexia” and “bulimia,” adding a supportive message before allowing a user to access these posts (see Figure 2).

However, these additional rules do not stop pro-ED support networks from sharing their ideas. Instead, new hashtags emerge, each one more removed from the original word than the other. Lee (2016) writes that “‘Thinspiration’ morphed into ‘thinspiration’; ‘ana’ into ‘annaa’” (para. 2). While these hashtags get blocked with time, new ones arise again and multiply, allowing the community to continue spreading information and “thinspiration”.

The portion of posts that get deleted on social media platforms have some similarities in their depictions of EDs. Chancellor, Lin, and De Choudhury (2016) argue that posts with self-harm and suicidal ideas are reported and removed from public view.

Therefore, the connection of EDs with other mental conditions is often monitored and acted upon, while other information, mostly related to weight loss and fitness, is not policed as harshly. Jade (n.d.) provides the term “orthorexia” – an unhealthy and unbalanced fixation on eating only healthy foods to lose weight. It is clear that the presentation of EDs evolves along with new social media restrictions, but the overall unhealthy relationship with food and the idea of weight loss remains present in the narrative.

Other Narratives and Potential for Change

The depiction of EDs as focused on beauty and thinness are prevalent both in anti- and pro-ED discussions. Nonetheless, it is not the only cause or reason for such disorders to appear. Featherstone (2017) shares a different view of this problem, noting that both mass and social media conversations fail to address multiple challenges to ED development. The author writes that her personal experience was not as connected to weight loss as the need to control her environment.

While her ideas were based on the thin ideal that she thought was established by society, it was not about thinness per se, but more about compliance and the desire to be regarded as “a good citizen” (Featherstone, 2017, para. 10). It is possible that some people who engage in restricting activities feel the same, but the current portrayal of EDs does not provide enough information about it to people struggling with eating problems, or the general public.

Limitations to the discussion about EDs are also mentioned by the National Eating Disorders Association that advises media sources to evaluate their portrayal of ED-related stories. Giordano (2018) supports Featherstone’s idea that the description of EDs is limited to a particular image. Young, white, straight women are seen as the only individuals who are susceptible to the disorder while men, people of color, and LGBT persons are often excluded (Giordano, 2018). This limitation fails to connect many people with EDs to the necessary resources. Moreover, it supports the stigmatization of the subject and incorrectly informs the public.

Both traditional and social media platforms can contribute to changing the narrative and providing help to people with, or at risk of, EDs. The first guideline that Giordano (2018) suggests is to curb the glamorization of the subject. All information should be shared to spread awareness and ensure people struggling with EDs that they are not alone and that recovery is attainable. This advice is more difficult to impose on social media representation as the latter is guided by the public.

Nonetheless, it is possible since various platforms already have ways for users to block or report potentially dangerous content with pro-ED ideas. Giordano (2018) also proposes the sharing of more information about those who may be going through similar experiences to include as many people as possible. This activity may help reframe EDs and remove the stigma of these disorders affecting only the young female population.

Conclusion

Overall, portrayals of EDs across traditional and social media still exhibit stigmatization and misinformed views. In the traditional media, printed publications and television programs release material depicting a limited number of stories, potentially restricting people’s access to information and reinforcing the idea of personal responsibility. Social media allows people to share information, thus encouraging dialogue.

However, while this platform can be used to dismantle the stigma surrounding EDs, pro-ED communities can also abuse the opportunity to promote the popularity of harmful behaviors. The main ideas behind social media’s portrayal of EDs are mutual support, self-hatred, and EDs as an identity or tool for goal achievement. Through this media, there are multiple possibilities for improving how people regard EDs. However, change requires significant time and effort from traditional publications and the public as well.

References

Chancellor, S., Lin, Z. J., & De Choudhury, M. (2016). “This post will just get taken down”: Characterizing removed pro-eating disorder social media content. In Proceedings of the 2016 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 1157-1162). New York, NY: ACM.

Featherstone, C. (2017). How I’m challenging 5 incorrect eating disorder myths in the media. The Mighty. Web.

Giordano, E. (2018). Mindfulness in media: How to improve eating disorder coverage. Web.

Greenwald, D. (2012). Lady Gaga reveals bulimia, anorexia battle, shares photos. Billboard. Web.

Holmes, S. (2018). (Un)twisted: Talking back to media representations of eating disorders. Journal of Gender Studies, 27(2), 149-164.

Jade, D. (n.d.). The media & eating disorders. Web.

Lee, S. M. (2016). Why eating disorders are so hard for Instagram and Tumblr to combat. Buzzfeed News. Web.

Lewis, S. P., Klauninger, L., & Marcincinova, I. (2016). Pro-eating disorder search patterns: The possible influence of celebrity eating disorder stories in the media. Journal of Eating Disorders, 4(5), 1-5.

Pater, J. A., Haimson, O. L., Andalibi, N., & Mynatt, E. D. (2016). “Hunger hurts but starving works”: Characterizing the presentation of eating disorders online. In Proceedings of the 19th ACM Conference on Computer-Supported Cooperative Work & Social Computing (pp. 1185-1200). New York, NY: ACM.

Rhydderch, D., Krooupa, A. M., Shefer, G., Goulden, R., Williams, P., Thornicroft, A.,… Henderson, C. (2016). Changes in newspaper coverage of mental illness from 2008 to 2014 in England. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 134, 45-52.

Yom-Tov, E., & Boyd, D. M. (2014). On the link between media coverage of anorexia and pro‐anorexic practices on the web. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 47(2), 196-202.