Economics Principle

A price ceiling is the highest legal price a seller may charge for a product and is normally set by the government or certain consumer groups, or “a legal maximum on the price at which a good can be sold” (Mankiw 2011b, p. 112).

The rationale of setting a price ceiling is to allow consumers to obtain some “essential” goods or services, in this case, housing, that they could not afford at the market-clearing price. Price ceilings are normally set below the market-clearing or equilibrium price in attempts to guard the interests of less fortunate consumers as “at this price, everyone in the market has been satisfied” (Mankiw 2011a, p. 77).

Demand Side Effects

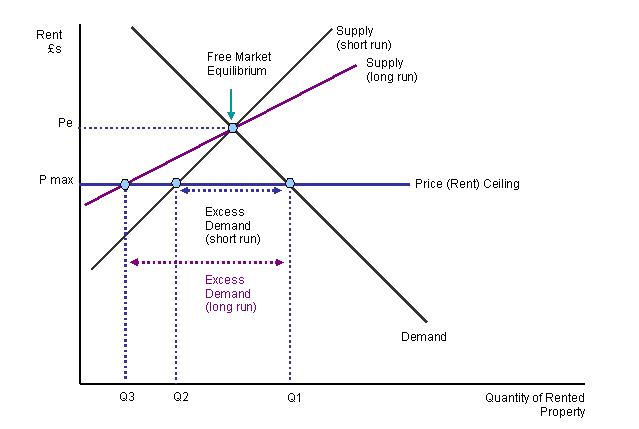

As rental ceilings set the rents below the equilibrium price, more people are then willing to have rental housing, and this may bring about an increase in the demand for the housing units at the new prevailing lower prices. This rise in demand remains both in the short run and in the long run (Mankiw & Taylor 2006, p. 112).

Supply Side Effect

Because of the low prevailing housing rentals, the suppliers (landlords) find it less attractive to supply more houses, and, therefore, in the short-run, they may suppress supply by selling the rental units to homeowners or converting their usage to other purposes (Gilderbloom & Appelbaum 1988, p. 10).

In the long-run, however, as the rent could be rising every year, the amount of growth allowed could be small hence making it unprofitable for the owners to service or repair the rental units.

If the control does not apply to office buildings and malls, many potential owners will prefer to invest more in those than in rental houses.

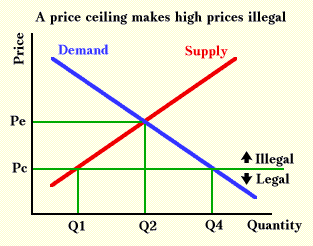

A black market occurs because some consumers are willing to pay more than the optimum price “when demand is greater than supply” (Capon & Hulbert 2007, p. 542). Considering the consumer surplus as the area above the market price and below the demand curve, their willingness to pay is a function of the slope of their demand curves. These consumers agree with owners to pay a higher price other than the set rents.

It is a market that is illegal in which the prevailing market price is higher than a legally imposed price ceiling (Jain & Ohr 2011, p. 76). Black markets build up in conditions where there is surplus demand for a product.

Without the price ceiling, the landlords would renovate the houses and pass such costs to tenants in increased rents. When this is impossible because of price callings, the landlords do not maintain the houses anymore, and it is not clear who gains in such a case. In the black market, on the other hand, the landlord gains from the increased rents at the expense of the tenants.

Fewer assets are allocated toward rental housing with the majority channeled to other uses. This would bring about the following:

- There is the inequitable distribution of rental houses with the landlords deciding on how to allocate the units they have. This is the problem that causes great inefficiency in the accommodation market.

- It would prevent the usual market adjustment in which competition among buyers bids up price inducing more production. Because rents are set at the ceiling, there is little tendency for potential tenants to pay above the ceiling, thus, suppressing supply in the market.

On the demands’ side, as rationing is more likely to occur, some potential tenants will be forced out of the market as the house owners resort to allocating their units to tenants in the market-leading to persistent market disequilibrium.

Government intervention in a market is necessary to correct market failures influencing directly the housing cost (Gilderbloom & Appelbaum 1988, p. 114). In the case of housing, the government can opt to provide low-cost housing to citizens who cannot afford the houses provided by the private sector at the equilibrium market prices. Government provision is when the state owns and provides the rental houses. It intends to produce at the socially optimum level.

To tackle administrative inefficiency, the government can give subsidies to private developers. This keeps healthy competition in the market; while enhancing the efficiency which is lost in the case of a state provider, this will increase the housing supply to meet the large demand.

Similarly, the government can opt to give the tenant’s income supplements. With such income supplements, the tenants who were not able to afford accommodation can do it now, and this will affect increased demand, hence, inducing the landlords to invest more in the rental houses.

Landlords can choose the tenants of their rental property through price discrimination. This occurs when the potential tenants are of different income levels and, therefore, have a different unique valuation of utility derived in staying in a given house and not in others.

In such a case, the house owners choose who their renters are by constructing units that meet the various unique tastes of the potential renters.

The landlords can also apply the general people’s preferences to stay in certain areas for various reasons, such as proximity in workplaces or locating away from urban centers, to select their potential tenants. This method makes the house owners build residential buildings in places that are convenient for their potential tenants.

Price Discrimination

This method is used by the landlords setting different rents and making consumers pay different charges for the same house (Jain & Ohr 2011, p. 238). Those potential tenants with a higher marginal willingness to pay for the houses are charged higher rents compared to those whose marginal ability to pay is lesser. This takes into account the premise that MU = P. In such a case, MU is the marginal utility capturing the marginal willingness to pay, and P is the price to indicate the rents paid.

The strong point of this method is that it is more practically feasible to separate the potential markets for various potential tenants based on their incomes as compared to trying to determine the residence preferences of potential tenants for their convenience.

Reference List

Capon, N & Hulbert, JM 2007, Managing Marketing in the Twenty-first Century, Wessex Publishing, New York.

Gilderbloom, JI & Appelbaum, RP 1988, Rethinking Rental Housing, Temple University Press, Philadelphia.

Jain, TR & Ohr, VK 2011, Principal of Microeconomics, FK Publications, New Delhi.

Mankiw, NG 2011a, Principles of Economics, 6th edn, South-Western Cengage Learning, Mason.

Mankiw, NG 2011b, Principles of Microeconomics, 6th edn, South-Western Cengage Learning, Mason.

Mankiw, NG & Taylor, MP 2006, Economics, Thompson Learning, London.

Maximum prices and black markets n.d. Web.

Price as a Rationer, n.d. Web.

Riley, G 2006, AS Market Failure: Maximum Prices. Web.