CCTV

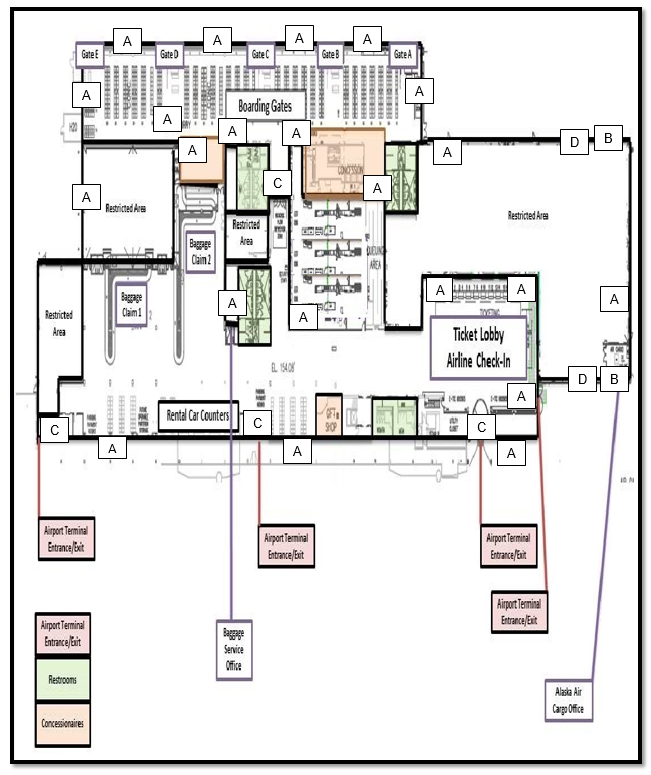

The closed-circuit television (CCTV) cameras should be positioned at the entry and exit points labeled A in the airport plan (Figure 1) to allow the monitoring of people. Given that entry points pose a lot of insecurity to the airport, CCTV cameras should be placed for critical surveillance of the landside where the public access freely. CCTV cameras are required at the landside because early identification and tracking of security threats are central to the prevention of assaults, thievery, robberies, kidnapping, hijacking, and terrorism (Szyliowicz and Zamparini 251).

CCTV at the landside should capture all cars that pick and drop travelers at the airport for security teams to track and trace them in case of insecurity incidences. Moreover, exit points need CCTV cameras to monitor what happens on the airside as people board and alight on planes (Szyliowicz and Zamparini 132). Beyond the boarding gates, the airside is prone to security threats, such as thievery, hijacking, and other acts of terrorism. CCTV would monitor passengers in the airside and allow security systems to flag potential security threats to both the airlines and people.

CCTV should also be positioned at the boarding areas of the airside, where passengers wait for their flights. The theft of luggage, jewelry, phones, and other valuables is common in the boarding areas. Since passengers usually spend some time in the boarding areas, some take drinks and eat snags, while others have a rest by napping, they are vulnerable to theft. In this view, concessionaries should have CCTV cameras for security to monitor travelers as they order, wait, and eat their food.

Hence, the presence of CCTV cameras would enable security officers to identify and arrest thieves, as well as restore stolen valuables to their owners. Queueing areas ought to have CCTV cameras to track the behaviors of passengers as they enter the airside of the airport. Robbery, thievery, and assault cases are common in this area due to the congestion of people. Corridors to restrooms should have CCTV cameras as thieves tend to hide and target their victims when they enter washrooms. CCTV cameras should also be placed in restricted areas to check the activities of authorized persons and alert security personnel in case of intrusions.

Check-in and ticket lobby should have CCTV cameras because it is a critical point of entry by passengers. A security flaw in check-in and ticketing systems would allow entry of untheorized people into the airside of the airport and cause major security incidences (Szyliowicz and Zamparini 129).

For instance, when cybercriminals access the check-in systems via unsecured links to customers, they can hack and enter their details as legitimate passengers. Also, during ticketing, criminals can impersonate passengers and gain entry into the airport where they undertake their criminal and terrorist activities. Baggage areas should also have CCTV cameras to ensure safety and accurate tracking and clearance of personal belongings at the airport. Often, thieves target the luggage of passengers and steal valuables before and during the screening process.

Access Control Points

Since the airport plan has restricted areas, it should have access control points to allow only authorized persons to enter. In the airport plan, access control points should be positioned in locations labeled B (Figure 1).

These positions are entry and exit points of the restricted area of cargo airlines. Merchandise in the cargo area requires protection from theft and destruction by arsonists and terrorists. Moreover, hazardous cargo needs careful handling and packaging to protect passengers and airport staff from undue harm. Access control points would allow authorized vehicles, cargo handling machines, and workers to undertake their work carefully without interference from intruders. In loading planes, an access control point at the airside is necessary to ensure that appropriate cargo exits stores to avert theft and misplacement.

Another vital section of the airport plan that requires access control points is the restricted area of the baggage. Screened baggage is normally stored in a restricted area awaiting their package into a plane. As the loss of luggage is common in airports, the use of access control points would prevent thieves and other unauthorized persons from interfering with arrangements. In case of the loss or misplacement of luggage, the authorized personnel would find it easy to trace and take responsibility for their duties. Owing to increasing cases of cybercrime, access control points are required in the ticket and check-in sections to prevent hackers from entering and accessing open systems. Employees of various airlines should ensure that their offices have access control points because they are vulnerable to cybercriminals. Therefore, access control points play a critical role in the safety of luggage and passengers in the airport.

Passenger Screening

Passenger screening should occur at check-in entry (C) to ensure that travelers do not go into the airside with weapons and arms (Figure 1). Criminals and terrorists usually attempt to sneak guns, missiles, grenades, and bombs into the airport through the check-in gates. Following the 9/11 attacks of 2001, it became evident that terrorism could use crude weapons to attack and hijack planes (Szyliowicz and Zamparini 238). Screening at the check-in points would enable the detection of any form of weapons and arms, which criminals and terrorists plan to use in their criminal activities. Overall, the safety of the airport is dependent on the effectiveness of passenger screening at the point of first entry into the airside.

Another level of passenger screening should be placed at the entrance to the boarding bay (C). Szyliowicz and Zamparini recommend pre-boarding screening, as well as random screening for passengers in airports (130). Screening of passengers for weapons and arms has proved ineffective because it does not detect smuggled goods, such as drugs and harmful chemicals, which comprise a security threat. Since drug traffickers and smugglers use their bodies to transport illegal products in and out of the country, passenger scanning should occur on entry and exit sites of the airside. Therefore, the double screening of passengers is necessary to guarantee the safety of airports and travelers.

Cargo Screening

Cargo screening should occur at entry and exit sites for cargo in the airport plan labeled D (Figure 1). These sites are critical because they allow vehicles and handling equipment to enter and exit the restricted area, a storage area for cargo. As cargo enters the restricted area, they should be screened for weapons and arms, such as grenades, missiles, bombs, bullets, and guns. Moreover, cargo should be screened for the presence of illegal and harmful products.

Given that cargo can stay for a long period in the airport awaiting custom clearance, they should be screened for the second time as they exit the airport to ensure that no illegal products are smuggled with them (Szyliowicz and Zamparini 94). Thus, additional screening is necessary for cargo handling to make sure that the status and conditions of goods for export or import do not change in the course of clearance by customs

Work Cited

Szyliowicz, Joseph, and Luca Zamparini. Air Transport Security: Issues, Challenges, and National Policies. Edward Elgar Publishing, 2018.