This presentation is devoted to a DNP project that involved a pilot change aimed at the improvement of pressure ulcers (PU) management at a Home Wound Care Program.

Introduction

- Topic: Pressure ulcers (PUs) management;

- Type: DNP change project, pilot change, EBP translation into practice;

- Presentation objectives: problem statement, PICOT, intervention, evaluation results, sustainability, recommendations.

This project encompassed an evidence-based practice (EBP) pilot change that targeted the issue of PU management at a Home Wound Care Program. The presentation is going to provide the key information on the project, including its PICOT question, intervention, and evaluation details.

Problem Statement and Purpose

- PU: significant, under-researched health issue (Bååth, Idvall, Gunningberg, & Hommel, 2013; Kruger, Pires, Ngann, Sterling, & Rubayi, 2013; Murray, Noonan, Quigley, & Curley, 2013; Sullivan & Schoelles, 2013).

- US: 60,000 patients annually (AHRQ, 2014).

- Practicum site: needs quality improvement.

The development of the project started with the determination of its significance. The need for researching Pressure ulcers (PUs) is well-established. PUs are a serious and highly prevalent issue. End-stage PUs (stages III and IV) are directly life-threatening; also, they can cause of sepsis and lead to multiple other complications like tissue necrosis or structure erosion (Kruger, Pires, Ngann, Sterling, & Rubayi, 2013). PU management is rather challenging, especially because it is rather common in older and physically impaired patients, who can be viewed as a vulnerable population and need to be treated with special care (Bååth, Idvall, Gunningberg, & Hommel, 2013). Moreover, the topic of PU management still requires additional research, especially with respect to specific populations and settings (Murray, Noonan, Quigley, & Curley, 2013; Sullivan & Schoelles, 2013). Finally, PUs are rather prevalent: in the US, about 60,000 patients per year experience the condition (AHRQ, 2014). In summary, PUs are a significant health issue that requires complex interventions, which makes it a national priority to develop the means of handling them with increased effectiveness in various healthcare settings. The DNP project offered its contribution to the discussion of the issue of PUs management, which establishes its theoretical value. As for the practical value, it is justified by the needs of the practicum site, which, among other things, include the requirements for continuous quality improvement in a variety of areas, including PU management.

PICOT

- Population: RNs and assistive personnel of the Home Wound Care Program (Jose V. Perez D.O.P.A, Miami Lakes, FL, USA);

- Intervention:

- an educational program based on the guidelines by AHRQ (2014);

- “PUSH tool 3.0” (n.d.);

- Comparison: pre-intervention quality of PU management (including populations’ knowledge);

- Outcomes: changes in PU management (desired outcome: improvement);

- Time: 8 weeks.

“For Registered Nurses and assistive personnel making home care visits for Jose Victor Perez DO, Miami Lakes, FL, does education on and implementation of the evidence-based Pressure Ulcer Scale for Healing (PUSH Tool) along with audit and feedback, lead to improved efficacy in the management and care of pressure ulcers over an eight-week period?”

The PICOT question formulation was the second step of the project development process. The PICOT elements of the project can be described in the following way. The population of interest included registered nurses and assistive personnel of the Home Wound Care Program who were arranged in teams for PU management. The intervention encompassed two elements: an educational program based on the recommendations of the AHRQ (2014) and the Pressure Ulcer Scale for Healing, which is also termed as the “PUSH tool 3.0” (n.d.). The educational program was used to help the population in the adoption of the PUSH tool, which was the core of the change aimed at the improvement of the quality of PU care in the settings.

The outcomes of the project included the changes in PUs management; the desired outcome consisted of the improvement of this parameter. The outcomes were compared to the pre-intervention state of PU management within the settings. This outcome was operationalized with the help of wound care data provided by the PUSH tool that tracked the rate and other specifics of PU healing throughout the project. Apart from that, the project views the participants’ knowledge concerning PU as an indicator of the quality of PU management within the program, and it was also measured with the help of a valid tool. The time period of the intervention implementation amounted to 8 weeks.

Theorist and Change Management

- Self-Care Deficit (SCD) by Dorothea Orem (Queiros, Vidinha, & Filho, 2014): self-care and patient needs; patient engagement and approaches to nursing.

- Iowa Model of Evidence-Based Practice (Iowa Model Collaborative, 2017): change model; guidance from issue identification to routinization and dissemination.

The theoretical and change management frameworks of the project were used to guide its further development. The Self-Care Deficit (SCD) theory by Dorothea Orem was employed for the nursing aspects of the project. Its concepts of self-care, patients’ needs, and the definitions of various approaches to nursing guided the patient engagement in the process of care (Queiros, Vidinha, & Filho, 2014), which was instrumental for the educational intervention for nurses. As for the change model, the well-established Iowa Model of Evidence-Based Practice was used by the project to guide the process of change adoption and routinization from the assessment of the organizational needs to the dissemination of the project’s results (Iowa Model Collaborative, 2017). This theory helped to adjust the change to the nurses’ needs, modify nurses’ behaviors, and convince them to routinize the new practice.

Project Methodology: Settings and Stakeholders

- Settings: Home Wound Care Program – Jose V. Perez D.O.P.A, Miami Lakes, FL, USA;

- Key stakeholders: nursing staff, administration, the project leader, patients;

- Need for the project: established by the stakeholders.

As can be seen from the PICOT question, the described DNP project employed an evidence-based educational program and a special tool for PUs assessment to improve the quality of PU care provided by the nurses of the Home Wound Care Program by Jose V. Perez D.O.P.A. The key stakeholders of the project included the nursing and administration staff of the project’s settings and the project leader. Also, the changes in the quality of PUs management were beneficial for the patients of the Home Wound Care Program. The fact that the Program was interested in promoting the project is proven by the letter of support provided by its administration; this acknowledgment of the Program’s need for improved PU care complements the above-mentioned importance of studying PUs and establishes the practical and theoretical need for the project.

Confidentiality

- No private/sensitive information obtained;

- Anonymous testing

- Uses codes: favorite color and three-digit code;

- Time of storing data: 7 years (Chamberlain College of Nursing requirement).

Ethical considerations were necessary to review before IRB decision. The project protected its participants and maintained their confidentiality. It did not gather any sensitive or private information, and it provided the opportunity for anonymization with the help of specific codes that consisted of colors and numbers. The anonymized gathered data will be stored for seven years as required by the college.

Ethical Considerations

- Risks: minimal: voluntary participation, consent, EBP intervention;

- Benefits: possibility of improved quality of care; facilitated PU management;

- Costs and compensation: none;

- No conflict of interests.

The project has studiously reviewed the potential ethical issues and has come to a conclusion that the risks of participation were minimal. Among other things, this fact was ensured by the voluntary sampling and the provision of all the information on the project to the potential participants during consent attainment procedures. The interventions could not affect the quality of life of patients in any negative way. The key potential benefit of the project was the possibility of the improvement of the quality of care in the program; however, it can also be suggested that the introduction of an easy-to-use and valid PU monitoring tool like PUSH is capable of improving the process of PU management, making it easier for the nurses. Thus, the benefits of the study outweigh the nearly non-existent and well-controlled risks. No compensation was offered to the participants, but the mentioned benefits and the opportunity to receive training on the use of a helpful tool has attracted a number of healthcare professionals. Finally, no conflicts of interest can be found in the project, which improves the objectivity of the study.

Project Design: Methodology

- Design: pre/posttest;

- Evaluation tools:

- Pressure Ulcer Scale for Healing (PUSH Tool);

- Pieper Pressure Ulcer Knowledge Test.

The project was designed as a pre/posttest study, which employed the Pressure Ulcer Scale for Healing (PUSH Tool) and the Pieper Pressure Ulcer Knowledge Test as its evaluation tools. As suggested by the design, the two tools were used to record the PU state and the nurses’ knowledge before and after the intervention to determine the respective outcomes of the project.

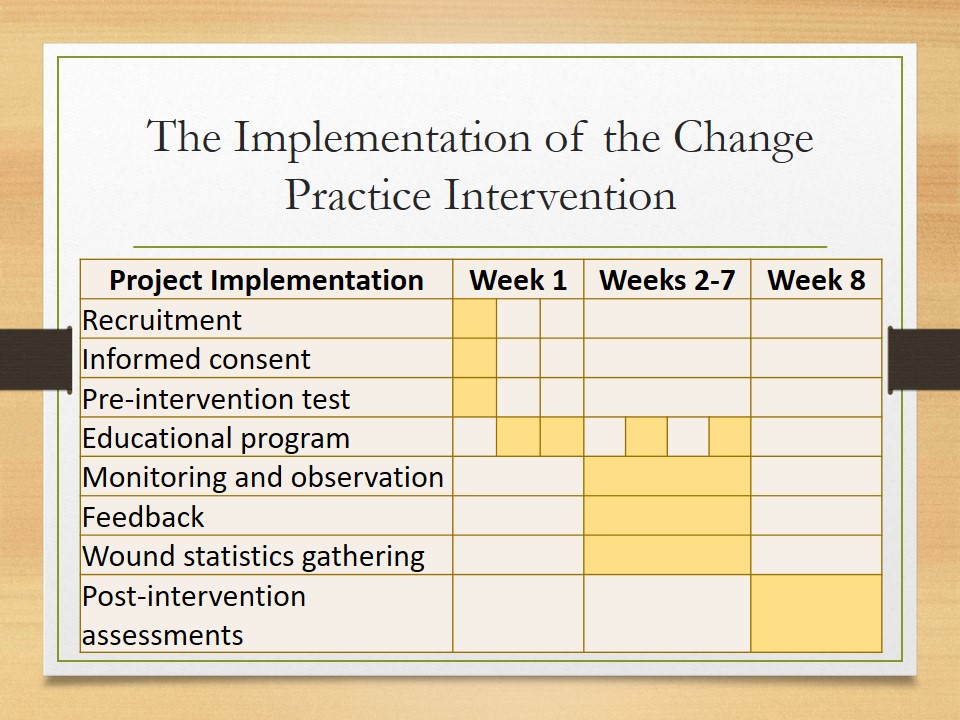

The Implementation of the Change Practice Intervention

The implementation phase has been carefully planned in accordance with the change model. A short version of the week-by-week implementation process is presented in this table. As you can see, the key activities of the implementation process can be divided into three stages: the preparational activities, which took place during week one, the bulk of the implementation process, which took place during the weeks 2-7, and the finalization activities, which were carried out during the last week.

Implementation: Week 1, Preparation

- Recruitment:

- Sample: 12 nurses; 20 patients.

- Method: informational correspondence.

- Consent procedures.

- Pre-assessment of knowledge, measurement: Pieper Pressure Ulcer Knowledge Test.

The first week incorporated some preliminary events, including the finalization of the recruitment process, the attainment of consent from the participants, and the pre-intervention evaluation procedures, which involved the assessment of the participants’ knowledge on PU management. The specifics of the tool used for this assessment will be discussed later. The sample of the study consisted of 12 nurses of the Home Wound Care Program. The nurses were recruited with the help of informational correspondence, and they were asked to choose one or two patients with PU, which resulted in a total of 20 patient subjects of the study.

Intervention: PUSH

Pressure Ulcer Scale for Healing (PUSH Tool):

- Developer: the National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel.

- Valid, tested in patients with different PU stages (Choi, Chin, Wan & Lam, 2016).

- Simple and easy to use and implement; popular.

As the primary intervention of the project, the PUSH tool should be discussed. The study focused on the implementation of the “PUSH tool 3.0” (n.d.), which was developed by the National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel. Apart from being created by a reputable panel with expert knowledge in healthcare, PU management, and EBP, this tool has been proven to be valid and applicable to PUs of different stages (Choi, Chin, Wan & Lam, 2016). Moreover, Choi et al. (2016) highlight the fact that PUSH is very often used in practice, which may be attributed to its simplicity. Indeed, the tool enables even the nurses with insufficient training in wound care to effectively monitor the healing progress. In general, Choi et al. (2016) report that nurses tend to find the tool easy to employ and incorporate into an organization’s practice. However, the Home Wound Care Program did not use this tool, which provided the project with an opportunity to test it in the settings and translate this piece of EBP into the program’s practice.

Implementation: Weeks 2-7

- The use of PUSH and AHRQ (2014) guidelines in practice;

- Monitoring & observation;

- Feedback;

- Data collection (e.g., wound healing – PUSH tool).

Most of the weeks were devoted to the introduction of the PUSH intervention supported by the AHRQ (2014) guidelines, including the educational efforts and the routinization of PUSH use. The process was observed both to collect data on the tool use and support the participants. The participants were asked to provide feedback so that their concerns could be addressed in time. Other data collection, in particular, wound healing statistics, took place throughout the implementation as well.

Implementation: Week 8

- Summative evaluation activities:

- post-intervention test, tool: Pieper Pressure Ulcer Knowledge Test;

- post-intervention wound state (statistics); tool: PUSH;

- Finalization of the implementation project; date of completion: 10/27.

Finally, the last week of the implementation process was devoted to summative evaluations, including the post-intervention assessment of knowledge and that of the PU healing process; both evaluations were carried out with the help of their respective tools. Thus, the implementation project was finalized during the 8th week, and the gathered data was stored for analysis. The date of the completion of the implementation phase was October 27th.

Implementation: Education Program

- Week 1:

- Three 1-hour sessions (workshops) on PUSH and AHRQ (2014) guidelines;

- Location: conference room;

- Led by: project leader;

- Weeks 1-7: feedback, follow-ups, monitoring.

The educational component of the process should also be discussed in detail. This element of the intervention mostly took place during the first week, but it could not be limited to it. The core of the intervention included three one-hour-long sessions based on AHRQ (2014) guidelines and led by the project’s primary investigator and leader. The number of sessions was chosen to offer an opportunity for the adjustment of the schedule to the convenience of the participants. However, the educational effort was extended beyond the first week: in particular, the process of the use of the PUSH tool was monitored, and the participants’ feedback was used to provide them with help and support in addressing the concerns that they have reported. These activities helped to customize the processes of education and change implementation, improving the chances of PUSH becoming successfully and fully adopted.

Data Collection: Types of Data Collected

- Qualitative: feedback, observations; thematic analysis;

- Quantitative: statistics, scores; statistical analysis;

- Data type: nominal, ratio;

- Key assessments: statistics on wound care (PUSH); nurse knowledge (Pieper test).

The implementation of the project was followed by its evaluation. The project involved a complex evaluation process that employed several tools. As a result, several types of data were collected, including nominal and ratio ones. Moreover, both qualitative and quantitative information was gathered, and it was analyzed accordingly: thematic analysis was employed for the former, and statistical analysis was used for the latter. The key evaluation tools of the project included PUSH and Pieper test, which are going to be reviewed in detail.

Evaluation: The Use of PUSH for Evaluation

- Outcomes assessed: PUs’ characteristics.

- Employed by: nurses.

- Validity and reliability: established (Choi et al., 2016).

- Timeline: formative and summative.

- Data type: quantitative (ratio, interval).

First of all, the quality of PU management was assessed through a continuous review of the state of PUs and their healing process carried out with the help of the same PUSH tool. Technically, the “PUSH tool 3.0” (n.d.) is meant for the continuous evaluation of the characteristics of PUs, which makes it an appropriate instrument. Also, as it was mentioned, PUSH has been proved to be an effective and valid tool in PU assessment (Choi et al., 2016), which means that it should produce accurate results. Since the use of the tool was also the intervention employed by the project, this form of evaluation was carried out by the participants during their daily PU management activities. The tool produces ratio and interval types of data, and it was employed both for formative evaluations that were used to modify participants’ activities and for the summative evaluation that determined the outcomes of the intervention during week 8.

Evaluation: Pieper Test

- Outcomes assessed: populations’ PU knowledge.

- Administered by: project’s leader.

- Validity and reliability: established (Pieper & Zulkowski, 2014).

- Timeline: pre- and post-intervention.

- Data type: quantitative (ratio score).

The second evaluation tool used by the project was the Pieper Pressure Ulcer Knowledge Test. It was employed to determine the changes in the participants’ PU management knowledge, which is an outcome of the project that is directly related to the quality of PU management. The test was administered by the project’s leader as a pre- and post-intervention test. It produces quantitative data (that is, a score), and its reliability and validity have been established (Pieper & Zulkowski, 2014), which makes it appropriate for the project.

Evaluation: Other

- Formative and summative; qualitative (nominal).

- Before, during, and after learning sessions: diagnostic questioning, teach-back.

- Throughout the process: feedback, staff work monitoring, and observation.

- End of project: study questionnaire.

Several additional approaches were employed throughout the project for formative evaluation, which was predominantly aimed at the improvement of the process of EBP adoption. Every teaching session involved a round of pre- and post-lesson diagnostic questioning, as well as feedback and teach-back, all of which were aimed at determining the progress of the participants and the aspects of the PUSH tool that they find difficult to master. This information was employed to improve the educational efforts and help the participants to learn PUSH usage faster. Moreover, the feedback from the participants was gathered continuously, and their progress in using PUSH was monitored through observation. These evaluations were used to ensure that the participants employ the tool correctly and to modify incorrect usage. Also, a study questionnaire was filled out to determine the nurses’ perspectives on the project. All the mentioned evaluations were meant to gather qualitative data, and they were analyzed with the help of thematic analysis.

Results

- Sample: 11 (55%) Stage III and 9 (45%) Stage IV PU.

- Extraneous variables:

- Malnutrition: not statistically relevant for healing time (S^2= 4.23405).

- Comorbidities: multiple, relevant for healing time; still indicated improvements.

The key results of the project can be presented as follows. The sample of the study included 11 patients with Stage III PUs (55%) and 9 patients with Stage IV PUs (45%). Several extraneous variables have been controlled during the study. In particular, malnutrition and comorbidities were reviewed to determine their effects on healing time. However, statistical analysis showed that malnutrition did not affect the healing time. Regarding comorbidities, multiple conditions were present in the patients, and some of them did affect healing time (for example, through decreased mobility), but the improvements were still present in the patients with comorbidities.

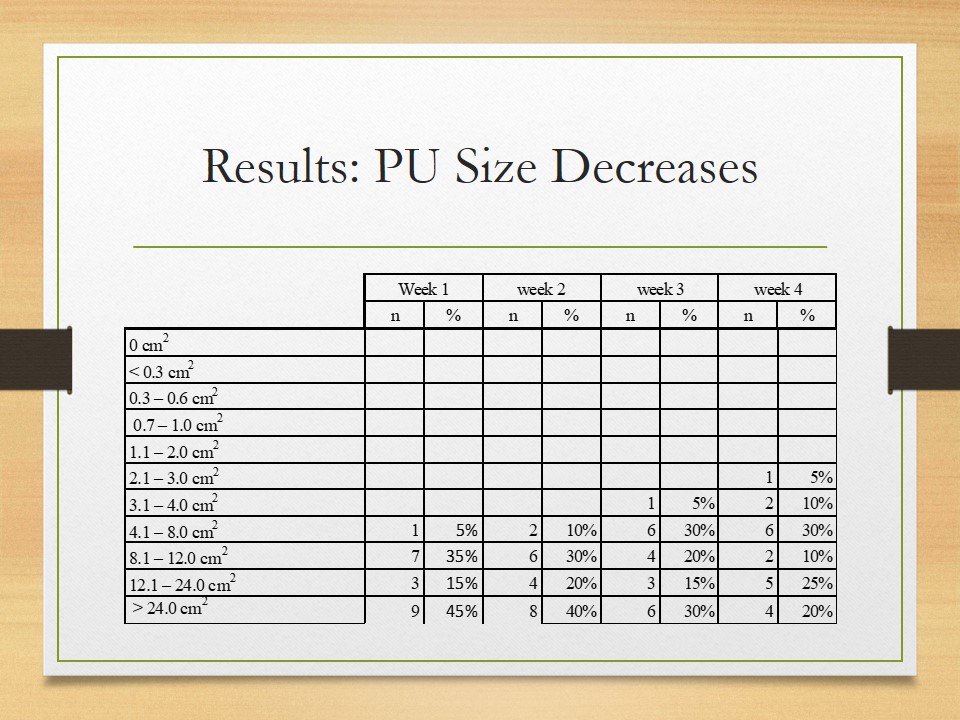

Results: PU Size Decreases

The PUSH tool produced detailed data on PU healing, which can, among other things, describe the size of wounds and its evolution. As can be seen from the figure on the screen, at the beginning of the project (before the intervention), 45% of PUs had the size that exceeded 24.0 cm2. The average wound size at the time amounted to 147.51cm2. The next four weeks showed relatively slow progress, but the fourth week demonstrated a notable decrease of wound size with only 20% of the wounds exhibiting the size of over 24.0 cm2.

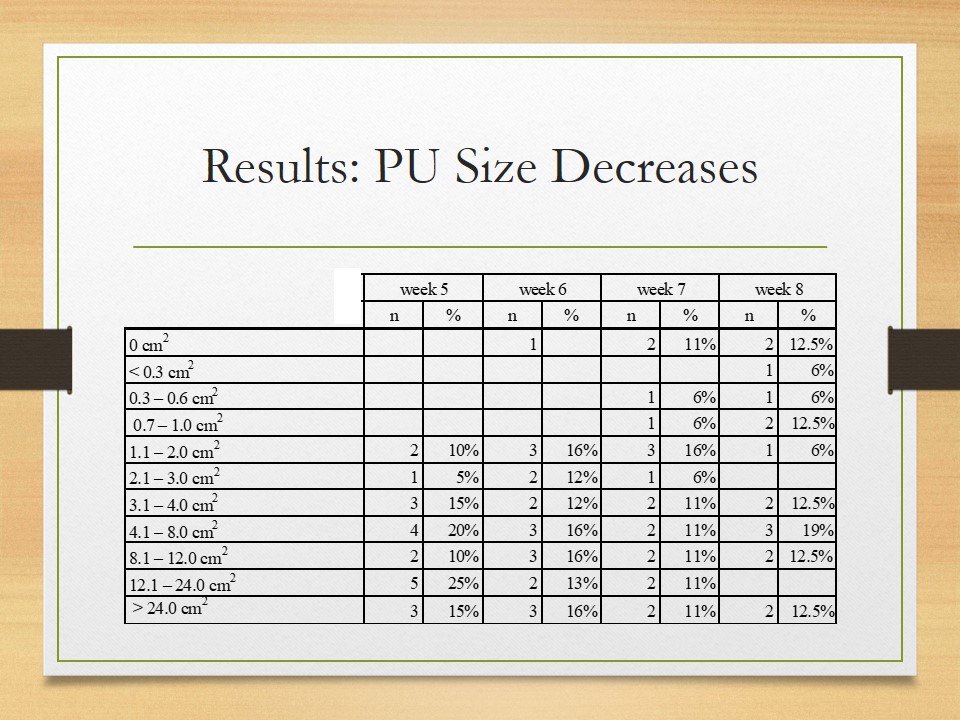

After that, the healing process proceeded with week 6 encountering the first fully healed patient. By week 8, only 2 wounds preserved the size of over 24.0 cm2, which was 10% of the total number of wounds and 12.5% of the wounds that remained unhealed at that point of time. Also, by week 8, a total of 5 patients were healed completely, and the average size of the wounds decreased by 94.56% to 13.78cm2.

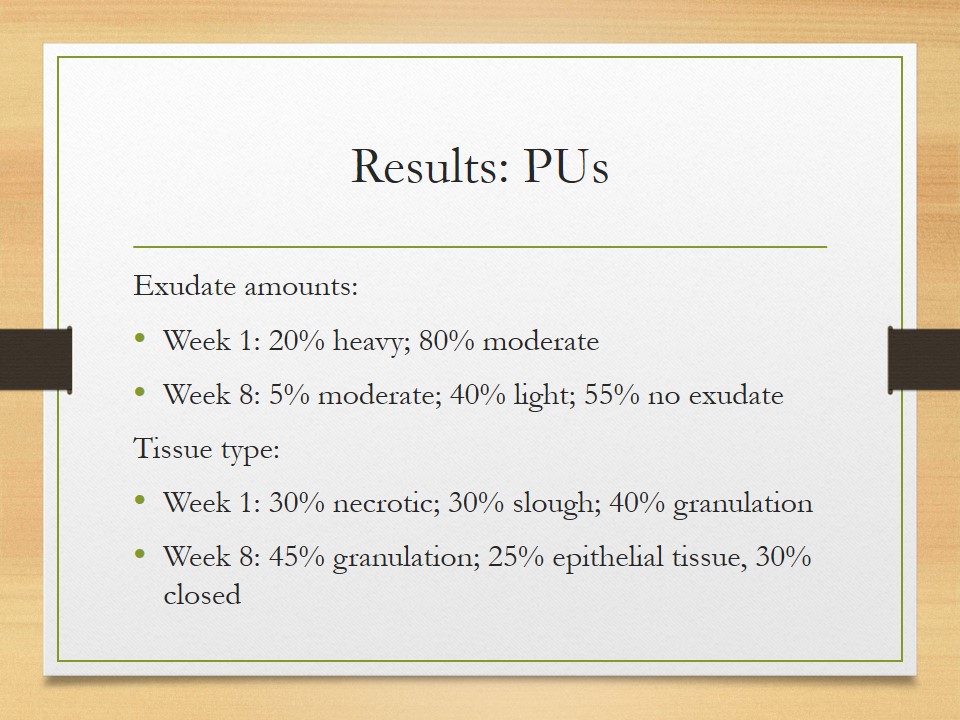

Results: PUs

- Exudate amounts:

- Week 1: 20% heavy; 80% moderate;

- Week 8: 5% moderate; 40% light; 55% no exudate;

- Tissue type:

- Week 1: 30% necrotic; 30% slough; 40% granulation;

- Week 8: 45% granulation; 25% epithelial tissue, 30% closed.

Other changes in the PUs included a notable decrease in exudate amounts and positive changes in the tissue type. In particular, while 20% of the wounds produced heavy exudate at the beginning of the project, 0% of them proceeded to do so at the end of the project. Also, the percentage of the wounds with moderate exudate amounts reduced from 80% to 5% (1 wound), and 11 wounds (55%) produced no exudate by the end of the project. As for the tissue type, no necrotic tissue or slough PUs were identified by the end of the project. In other words, the PUSH tool indicates that the project has been successful in treating the PUs by ensuring various improvements in 100% of the patients, which answers the PICOT question.

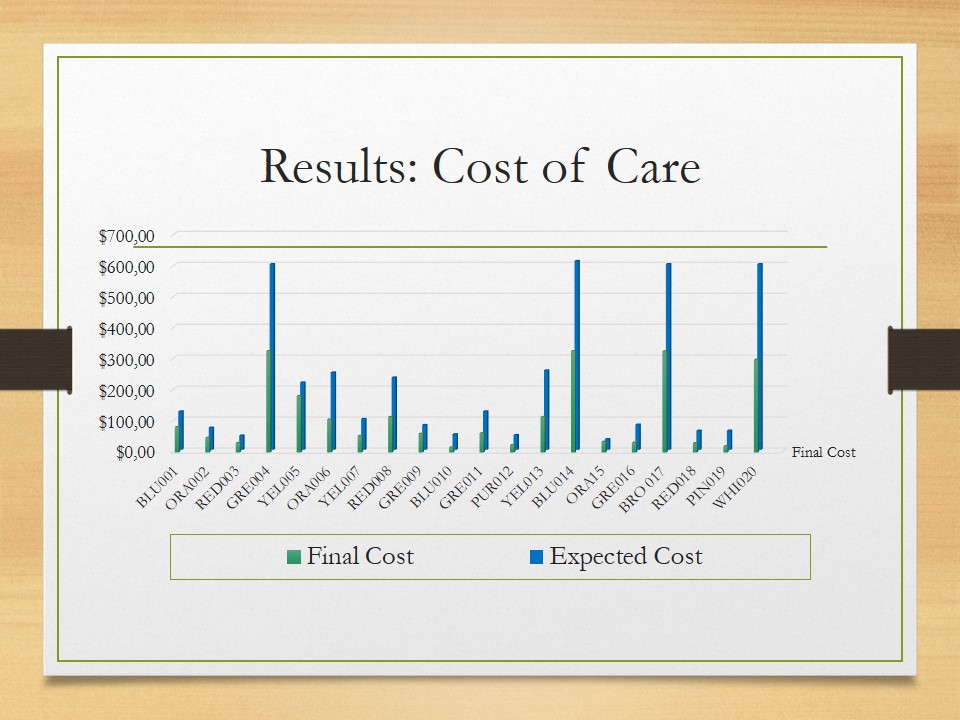

Results: Cost of Care

It is also noteworthy that all the participants noted a decrease in the cost of care: the tested approach was almost 50% less costly when compared to the costs that were anticipated based on the data describing the standard approach.

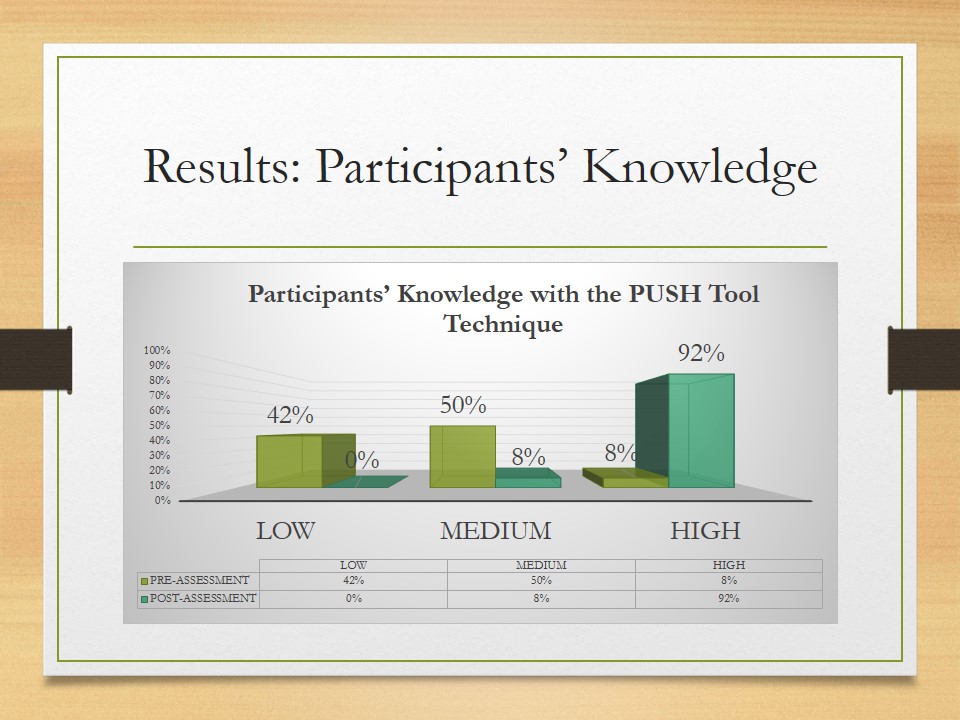

Results: Participants’ Knowledge

The Pieper Pressure Ulcer Knowledge Test demonstrates the effectiveness of the educational component of the project. In particular, only 8% of the participants had exhibited a high knowledge of PU management prior to the intervention, but after it, 92% of the nurses showed high results. Moreover, while 42% of the participants had demonstrated low knowledge of PU management prior to the intervention, after it, 0% of them were shown to have such results. Thus, the educational component of the project was most effective.

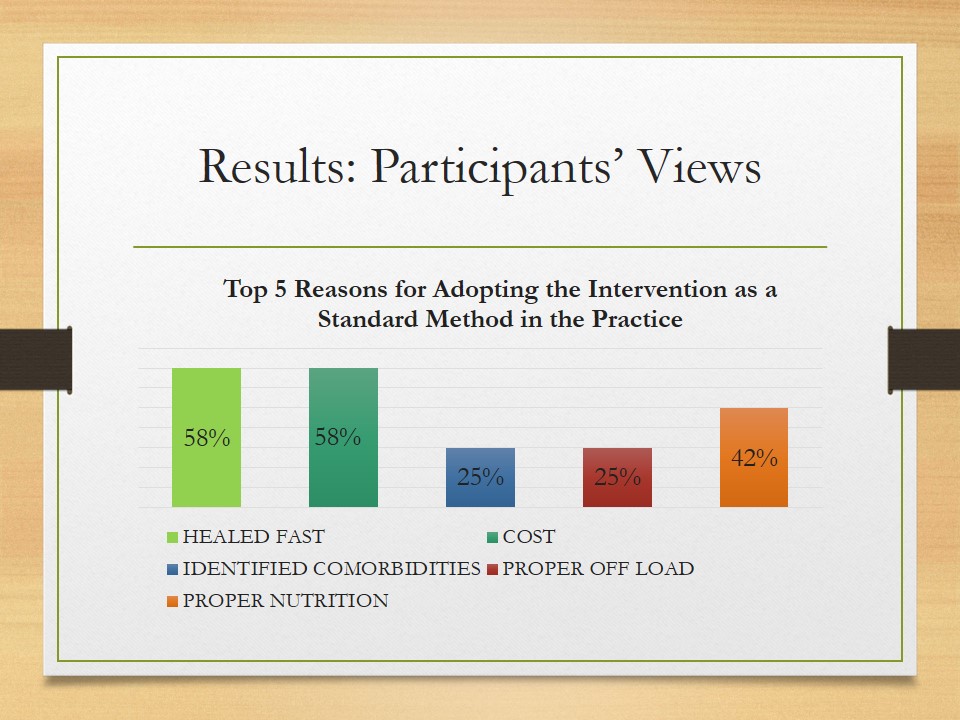

Results: Participants’ Views

Regarding feedback, it is important to note that 100% of the participants approved of the project and made positive comments about it. When asked to highlight the primary advantages of the intervention, the nurses named five key areas. Seven of the nurses (58%) were especially satisfied by the fact that the intervention resulted in fast healing, and seven more participants highlighted reduced costs. Also, the intervention facilitated proper nutrition, which was pointed out as the primary reason for tool adoption by five participants, and other nurses noted comorbidities identification and proper offload as the major advantages of the intervention.

Dissemination

- Home Wound Care Program leaders: the paper.

- Chamberlain College of Nursing: presentation and Q&A.

- Additional journal publications and presentations.

- Confidentiality: de-identification.

The results of the study will be presented in the form of a final report and presentation. No identifying data will be present in either. A copy of the paper will be provided to the Home Wound Care Program leaders; also, a presentation of the results will be shared at the Chamberlain College of Nursing. The peers who will attend the presentation will also be welcome to ask questions on the project. It is possible that the results will be published in scientific journals and presented at other events, but no direct plans are made in this respect yet.

Sustainability

- Iowa model: pilot change.

- Barriers:

- resources shortage;

- communication issues (cultural diversity);

- individual innovation adoption concerns;

- individual resistance to change.

- Sustainability facilitators:

- reliable change model;

- organizational culture of the settings;

- enthusiasm of the participants;

- achieved outcomes.

An important part of the implementation phase is the consideration of the sustainability of the change. From the perspective of the Iowa model, the discussed project is a pilot change. As a result, its outcomes are important for a more comprehensive change within the settings. In particular, the pilot change indicates that the barriers to the process can include the shortage of resources and communication issues. These issues have been mitigated through careful budgeting and feedback, which implies that these methods can be later employed by the future change. Also, the feedback from the participants indicated that personal concerns related to the adoption of the PUSH tool need to be addressed; during the pilot change, they were reviewed individually. Mostly, nurses were interested in the tips on patient education and the details of patient needs management. Finally, the individual resistance to change should also be noted; during the pilot change, it was almost non-existent and predominantly caused by the mentioned concerns. As a result, the determination and resolution of concerns is a viable strategy for resistance reduction.

Apart from the evidence on the barriers, the project has provided some data on the possible facilitators. First, the selected change model should make it easier to achieve sustainability since it provides a framework for a successful integration of change into practice. Moreover, the organizational culture has been supportive of the project, which will help the change in persisting even after the project is completed. Furthermore, the enthusiasm of the participants who have approved of the project and PUSH may be helpful in promoting the future change. Similarly, the outcomes that have been achieved so far should offer some motivation for future participants. In summary, the project has provided some information and tangible outcomes that can contribute to the sustainability of the future change.

Implications for Practice

- Meso-level (Wound Care Program): pilot study successful; can proceed with the change.

- Macro-level: contribution of evidence concerning the under-researched topic of PU management (Sullivan & Schoelles, 2013).

- Limitations: short-term pre/posttest pilot study, small sample.

As a pilot change, the described project is of direct use for the studied Wound Care Program: as the pilot change proved to be successful, it will be followed by a full-fledged change that will take into account the barriers, facilitators, and outcomes of the project to ensure a customized and sustainable change. On the macro level, the project demonstrates the effectiveness of the tested intervention in improving PU management, which is a contribution to this under-researched topic that can be of interest to the healthcare community in general (Sullivan & Schoelles, 2013). However, the study was a pilot change which involved a relatively small sample and did not track any long-term changes in the quality of care. Also, it only compared PUSH’s cost-efficiency to that of other interventions; PU healing outcomes were compared using the pre/posttest methodology. Future studies can rectify these limitations by testing the intervention for prolonged periods of time with a larger number of participants and in comparison to other interventions.

Conclusion

- Issue: PU management.

- Intervention: PUSH tool – valid, reliable.

- Evaluation: PUSH and Pieper test.

- Outcomes/recommendations: the tool results in effective, cost-efficient, simplified PU management.

- Questions?

To sum up, the project considered an approach to the management of a significant healthcare issue (PU management) in the settings of the Home Wound Care Program and within the period of eight weeks. The process of the project’s development started with establishing the need for it and involved the careful planning of the implementation phase and the choice of appropriate tools and methodology. As a result, the project focused on the implementation of the evidence-based PUSH tool in the everyday practice of the program. To ensure the success of the implementation, it was supported by training and the use of AHRQ (2014) guidelines. The Iowa change model and SCD comprised the theoretical framework of the project. The outcomes of the study were evaluated predominantly with the help of PUSH and Pieper test, both of which have been proved to be valid. The specific outcomes involved effective, cost-efficient, and simplified PU management, which was approved by the participants; therefore, the use of the PUSH tool can be recommended for practice. The project’s results were helpful to the Wound Care Program, but they can also be of interest to the healthcare professionals and leaders who are engaged in PU management or want to investigate an example of EBP translation to practice.

If you have any questions, please feel free to ask.

References

AHRQ. (2014). Preventing pressure ulcers in hospitals: Are we ready for this change. Web.

Bååth, C., Idvall, E., Gunningberg, L., & Hommel, A. (2013). Pressure-reducing interventions among persons with pressure ulcers: Results from the first three national pressure ulcer prevalence surveys in Sweden. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 20(1), 58–65.

Choi, E., Chin, W., Wan, E., & Lam, C. (2016). Evaluation of the internal and external responsiveness of the Pressure Ulcer Scale for Healing (PUSH) tool for assessing acute and chronic wounds. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 72(5), 1134-1143.

The Iowa Model Collaborative. (2017). Iowa model of evidence-based practice: Revisions and validation. Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing, 14(3), 175-182.

Kruger, E. A., Pires, M., Ngann, Y., Sterling, M., & Rubayi, S. (2013). Comprehensive management of pressure ulcers in spinal cord injury: Current concepts and future trends. The Journal of Spinal Cord Medicine, 36(6), 572–585.

Murray, J., Noonan, C., Quigley, S., & Curley, M. (2013). Medical device-related hospital-acquired pressure ulcers in children: An integrative review. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 28(6), 585–595.

Pieper, B., & Zulkowski, K. (2014). The Pieper-Zulkowski Pressure Ulcer Knowledge Test. Advances in Skin & Wound Care, 27(9), 413-420.

PUSH Tool 3.0. (n.d.). Web.

Queiros, P.J., Vidinha, T.S. & Filho, A.J. (2014). Self-care: Orem’s theoretical contribution to the nursing discipline and profession. The Journal of Nursing Reference, 4(3); 157-163. Web.

Sullivan, N., & Schoelles, K. M. (2013). Preventing in-facility pressure ulcers as a patient safety strategy: A systematic review. Annals of Internal Medicine, 158(5), 410–416.