Introduction

Personality profiling is an important psychological tool for critically evaluating aspects of an individual, allowing for deeper study, understanding, and recognition of aspects of individuals’ behavior and motivations. Profiling is used in many areas related to the implementation of social services because this method is paramount to more highly effective interactions with the individual. This includes any individual or group counseling, psychotherapy, interviewing job applicants for employment, administrative leadership readiness checks, and any other industry in which in-depth personality testing is necessary to optimize outcomes. This paper uses the educational settings of schools, colleges, universities, and any other educational setting in which a teacher comes into contact with students as the medium. The basis for this critique letter is the claim that “Personality profiling has no use or value in educational settings. It may be noted that this is a very bold statement that may contradict the cores of the disciplines that study personality profiling as a psychometric tool. This paper provides a critical discussion of this phrase, identifying any arguments in its favor and counterarguments, using the academic literature as sources of verified information. Thus, the critical letter is a valuable resource for all students of pedagogy and psychology, as well as anyone interested in learning more about the topic of personality profiling.

Brief Background Information on Personality Profiling

It is worth noting that personality profiling is not an unambiguous term and does not find a strict definition in the academic community. For example, Yunus (2018) describes profiling as the process of systematically recording personality for later analysis. From this definition, it is clear that any personality is descriptive and thus has specific, measurable characteristics. At the same time, Saad et al. (2018) show that the use of profiling tools produces outcomes that can influence the social behavior of individuals. In other words, the outcomes of the personality profiling procedure have psychological value, so this tool proves to be essential for communities and individuals. It is not uncommon to see studies that examine the applicability of personality profiling to structures of interpersonal interactions, such as employee relations (Manna, 2019). The same can be applied to the school, as shown by Meier & Carroll (2020): this study explains the possibility of using personality profiling as a tool to assess individuals’ leadership skills. If one turns to Figure 1, however, one finds noteworthy facts. The total number of scientific papers located in the Web of Science digital database under the “personality profiling” tag is not focused on individual fields of knowledge but instead is differentiated by clusters. Thus, in addition to psychiatry, social and clinical psychology, the study of personality profiling is implemented in neuroscience, educational disciplines, behavioral biology, criminology, management, and even computer science. In other words, this aspect of the behavioral sciences is fundamentally important to the academic community, and so using the literature seems a valid strategy for exploring the argument for the initially stated claim.

The Possibilities of Personality Profiling for the Classroom

The basis for the bold statement under discussion is the widespread practice of using personality profiling in academic settings. By accepting the possibility of using this tool to measure the sides of students’ personalities, teachers are often trying to optimize the learning process. It is not about simple tests assessing an individual’s personality through a series of unrelated practices but about using evidence-based theoretical concepts to identify students’ levels of awareness, success, intelligence, and appropriateness. When a teacher begins working with a new class, it is always challenging to explore the climate and get to know the children more deeply. It is not enough to know a student’s name, gender, or essential hobbies in order to effectively build a lesson and tap into the full potential of each individual. For this reason, personality profiling is a widespread practice for teachers who want to set up an academic classroom environment uniquely. One of the best known is the Myers-Briggs test, or “sixteen personalities,” which allows for the most accurate and precise identification of a student’s personality traits in a pool of sixteen choices. This test is often used in case studies to test the personality characteristics of respondents (Scott et al., 2021; Hamm, 2018). There are also alternative methods of personality testing, which, however, do not have such a high level of academic reliability. These include, for example, the Free Personality Test, which consists of 28 core questions and four demographic questions (Advance, 2020). This test can be a helpful alternative to the Myers-Briggs test because they have similar questions but meaningfully different numbers of questions.

Academic Perspectives on Personality Profiling

Finally, when the nature and necessity of using personality profiling in an academic setting are no longer in question, a critical assessment of the value and usefulness of such procedures should be provided. To this end, it is paramount to note that using personality profiling tools does not mean categorizing students or assigning labels to them. Calling students “capable” or “smart” is fraught with negative consequences and unethical categorization. Instead, the personality profiling procedures discussed next are seen as mechanisms for introspection and a deeper understanding of oneself as an individual. To put it another way, personality profiling is used in this section not as a benefit for the teacher alone but as a comprehensive benefit for the entire classroom.

It is believed that if an academic goal is articulated concretely, accurately, and strategically, the use of personality profiling for the classroom proves to be an extremely effective technique. There is robust evidence that emphasizes that personality is a measurable system, and thus the use of personality profiling is appropriate. For example, Utami et al. (2021) recognize that using the five-factor OCEAN test is highly valuable for categorizing the full range of human personality capabilities: in other words, OCEAN is self-sufficient and redundant for use, and thus its applicability in the classroom proves useful. Williamson (2018), who pointed to the use of OCEAN by major social platforms (including Facebook) to create a behavioral portrait of users for more effective marketing during the U.S. election, agrees. While the academic environment is not political, there are no limitations to extrapolating the tests used outside of school into the classroom environment. It is noteworthy that OCEAN is developing new, more refined models for assessing students’ emotional intelligence. Specifically, it is talking about the computerized questionnaire from OECD — this test is based on the belief that student achievement is a function of a student’s emotional well-being and social skills, which in turn can be measured by tests (Chernyshenko et al., 2018). As a corollary to this statement, one would expect that the use of personality profiling can become predictors for detecting improvements in student achievement. This has been proven by Waite & McKinney (2018), who administered the Myers-Briggs test to 48 students. A key finding of their labors is that critical thinking skills — thinking and judgment along with feeling instead of intuition — were most developed among students with personality types INFP (mediator), ISTJ (administrator), and INFJ (activist). This information is of little use for the current work exploring the correlations Waite & McKinney were interested in but is strategically vital as a counterargument to the stated assumption. In other words, each of the works discussed in this paragraph has shown that personality profiling tests are widely used in social studies and help gain more profound knowledge about student personality.

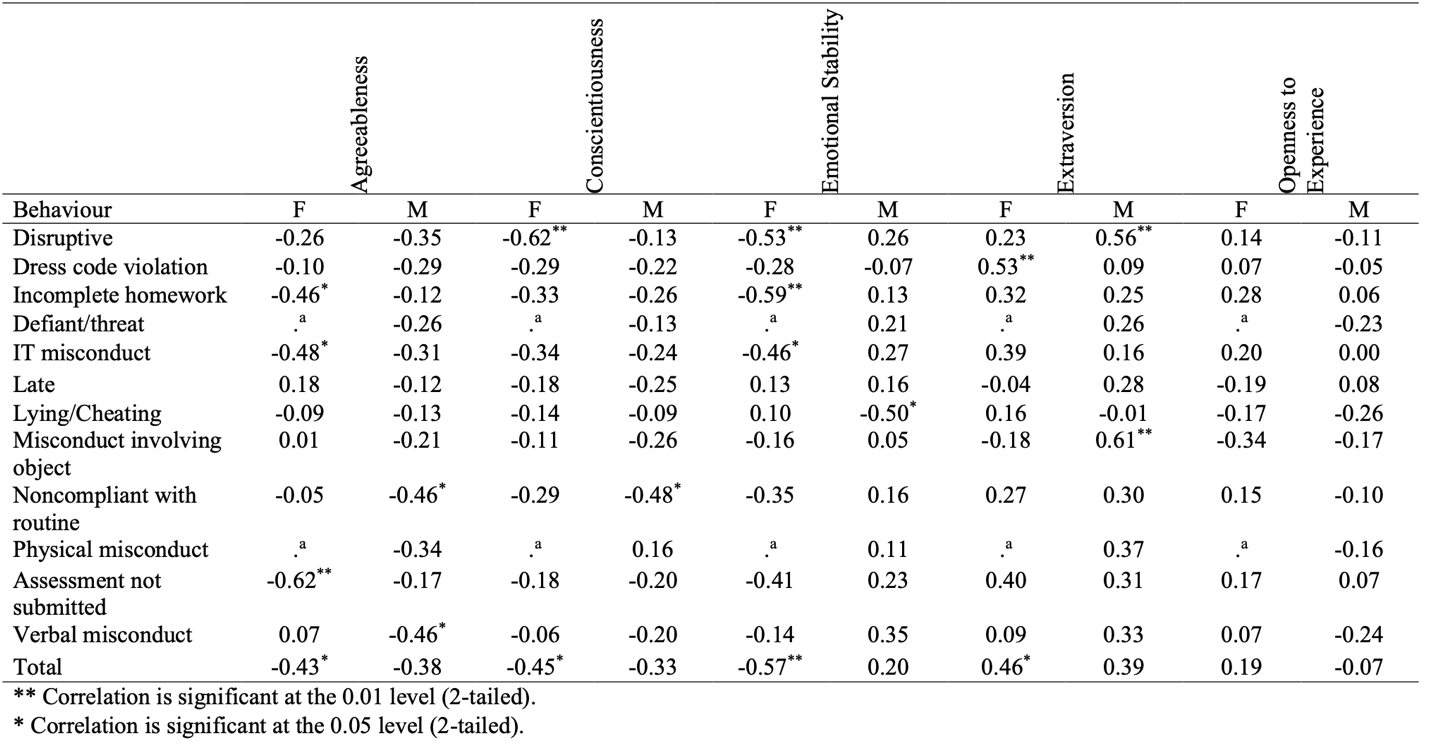

An important issue is determining the relationship between a student’s personality traits and educational outcomes, as this determines the value of profiling as a tool. In his work, Smith (2019) demonstrated in detail the correlation between high school students’ personality traits and their behavioral patterns. More specifically, Smith indicates a correlational relationship between personality traits, genders, and specific episodes of unwanted student behavior. Figure 2 reflects these patterns: it can be seen that of all the traits, emotional stability in girls shows the greatest strength of negative correlation with such patterns, whether they be school uniform violations, lying, tardiness, and other acts of deviant behavior. It follows that measuring personality by dimensions, as part of profiling, has proven value in correlating with potential classroom threats. In other words, profiling students at the beginning of the year can give teachers early material to adjust classroom behavior to avoid threats and problems.

The initially stated thesis postulates that personality profiling has no use in academic settings. In fact, this is false because one of the most commonly used tools in any classroom is reflection. Reflection helps students look back and critically evaluate their successes or weaknesses to adjust their future professional development plan (Bass et al., 2017). Although not evident, during reflection, the student engages in their profiling as they try to fragment their personality and experiences into parts to examine them individually. Additionally, reflection does not necessarily have to be individual, as both group and collective reflections on experience have places in academic practice (Johnston & Fells, 2017). The heart of reflective school reflection is always the individual and their relationship to the environment, which means that each class is constantly profiling without explicitly emphasizing it.

Another vital resource that shapes the value of personality profiling in the classroom is the setting of long-term benchmarks. A multitude of tests, including the already well-known Myers-Briggs instrument, allow students to learn deeper details about their personality type and discover traits perhaps not previously explicit to them and encourage them to create goals. Specifically, if the personality description indicates that ENTP-A / ENTP-T type personalities cannot resist an intellectual challenge, this can be a motivating factor for these students to engage in debate and actively respond in class simply because it is a characteristic of them (Debater, n.d.). At the same time, a teacher in such a classroom can create goals commensurate with students’ abilities, the achievement of which can become a weekly or semester-long goal. In more detail, a one-way analysis of variance by Suamuang & Suksakulchai (2020) demonstrated that students with higher achievement tend to perceive goal orientation lower than students with average achievement. In the context of this paper, it follows that the ability to set goals and follow through on them may be a predictor of student achievement.

It is not uncommon for middle and high school students to be characterized by increased stress and apathetic states, especially during inconsistent COVID-19 times. A study by AlAzzam et al. (2021) shows that about two-thirds of the students surveyed reported anxiety. In this sense, using personality profiling as a method of profound self-discovery helps students within the classroom, first, to understand that their character is perfectly normal, and second, to recognize strategies for managing disruptive states for themselves. Students who learn that they are susceptible to stress are likely to perceive their anxiety differently and perhaps even learn how to manage it (Yalçin, 2019). In other words, personality profiling in this context can be identified with recognizing the naturalness of one’s personality traits and using them as strengths.

However, it is fair to emphasize that personality profiling mechanisms can be dysfunctional, as evidenced by some authors. Kim Perkins, an expert in positive educational psychology, clearly shows that personality profiling results are ineffective and invalid because they reflect absolutely anyone (Perkins, 2019). Specifically, Perkins shows that any formulation that is as neutral as possible can be reflected in any reader, and for this reason, the use of personality tests is impractical because it is not an adequate portrayal of a student’s internal reality (Reynolds et al., 2021). This makes sense because, as a rule, subjects tend to agree with the results of profiling, especially if they praise them or emphasize individuality. Furthermore, Perkins adds that if measurable outcomes depend on personality tests, subjectivity cannot be avoided. If a teacher indicates that personality profiling results will determine the division into teams and pairs in class, it is almost certain that students will try to achieve skewed results to get their desired results. For this reason, Perkins disagrees with the mechanics of using such tests in an academic setting.

Similar discussions can be found in several scholarly publications highlighting the use of personality profiling tools. For example, Meier & Carroll (2020) point out that profiling raises many pedagogical and methodological problems. A critical problem in this sense is the inconsistency and subjectivity of the results offered by researchers. The widespread use of personality measurement tools, according to the authors, is fundamentally flawed and cannot produce objective results because psychological attributes of personality are not quantified at all. Laajaj et al. (2019) also showed that the critical five personality trait test is not universally applicable to subjects from different countries because the cultural background of each region can impose changes on personality. Thus, there is a threat to the reliable use of common personality profiling tests for different regions and even schools.

Conclusion

In conclusion, it should be emphasized that personality profiling does not have unequivocal assessments from the academic community. On the one hand, it is a heavily psychometrically weighted instrument that adapts perfectly to classroom settings. Conducted at the beginning of the school year, profiling helps the teacher understand the class and optimize behavioral and academic performance. On the other hand, profiling had no proven, actionable, and reproducible results, which could mean a high level of bias and subjectivity. As is evident, there is no consensus on the primary stated question. However, it is worth saying that the use of personality profiling in the classroom can yield valuable and valuable results if the teacher is fully aware of the degree of responsibility for the conclusions and the possible consequences of inaccurate interpretations of students’ identities.

References

Advance. (2020).Free personality test. Personality Perfect.

AlAzzam, M., Abuhammad, S., Abdalrahim, A., & Hamdan-Mansour, A. M. (2021). Predictors of Depression and Anxiety Among Senior High School Students During COVID-19 Pandemic: The Context of Home Quarantine and Online Education. The Journal of School Nursing, 37(4), 241-248.

Bass, J., Fenwick, J., & Sidebotham, M. (2017). Development of a model of holistic reflection to facilitate transformative learning in student midwives. Women and Birth, 30(3), 227-235.

Chernyshenko, O. S., Kankaraš, M., & Drasgow, F. (2018). Social and emotional skills for student success and well-being: Conceptual framework for the OECD study on social and emotional skills. OECD Education Working Papers, 173, 2-112.

Debater. (n.d.). 16Personalities.

Hamm, S. C. (2018). The Myers-Briggs type indicator and a student’s college major [PDF document].

Johnston, S., & Fells, R. (2017). Reflection-in-action as a collective process: Findings from a study in teaching students of negotiation. Reflective Practice, 18(1), 67-80.

Manna, D. R. (2019). The effects of emotional intelligence on communications and relationships. Journal of Organizational Psychology, 19(6), 63-67.

Meier, F., & Carroll, B. (2020). Making up leaders: Reconfiguring the executive student through profiling, texts and conversations in a leadership development programme. Human Relations, 73(9), 1226-1248.

Laajaj, R., Macours, K., Hernandez, D. A. P., Arias, O., Gosling, S. D., Potter, J.,… & Vakis, R. (2019). Challenges to capture the big five personality traits in non-WEIRD populations. Science Advances, 5(7), 1-13.

Perkins, K. (2019). Personality tests don’t work, here’s why and the alternatives. Nobl Academy.

Reynolds, C. R., Altmann, R. A., & Allen, D. N. (2021). The problem of bias in psychological assessment. Mastering Modern Psychological Testing, 573-613.

Saad, M. S., Yunus, A. R., Kamarudin, M. F., & Ibrahim, I. (2018). An integrated personality profiling framework to identify and produce talent in a technical university. World Transactions on Engineering and Technology Education, 16(1), 80-83.

Scott, J., Castelli, J., & Valdes, K. (2021). The use of a temperament test to increase HEP adherence. Journal of Hand Therapy, 34(1), 142-144.

Smith, A. (2019). High school student personality and misbehaviour [PDF document].

Suamuang, W., & Suksakulchai, S. (2020). Perfection of learning environments among high, average and low academic achieving students. In A. M. Wydawnictwo (Ed.), The New Educational Review (pp. 76-86). Toruń: Wydawnictwo Adam Marszałek.

Utami, E., Hartanto, A. D., & Raharjo, S. (2021). Systematic literature review of profiling analysis personality from social media. Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 1823(1), 1-9

Waite, R., & McKinney, N. S. (2018). Personality typology: Understanding your preferences and striving for team effectiveness. ABNF Journal, 29(1), 2-11.

Williamson, B. (2018). Why education is embracing Facebook-style personality profiling for schoolchildren. The Conversation.

Yalçin, A. S. (2019). Self-recognition and understanding others. In P. A. Chernopoloski (Ed.), Recent Studies in Health Sciences (pp. 535-545). Sofia: St. Kliment Ohridski University Press.

Yunus, A. R., Hassan, S. N. S., Kamarudin, M. F., Majid, I. A., & Saufi, N. S. M. (2018).Integrated personality profiling for academic performance [PDF document].