Introduction

Exporting camel meat from Australia to China is a lucrative business venture, but it has risks associated mainly with competition and the lack of adequate marketing structures in both the origin and the destination country. Nevertheless, as the report shows, starting the business is a good idea, given that the economic outlook of China is improving, its population is growing, the middle-income status of households is increasing rapidly, and the demand for alternative food is growing. China is also a historical trading partner with Australia and authorities in the two countries are keen to promote a mutual trading environment.

Australia already has a thriving beef export business in China and faces few hurdles in replicating the same success with camel meat. One of the challenges facing Australia would be the wild nature of camels found in the country, which hampers the proper planning of production and processing of meat for export. In addition, the camel meat export industry needs to develop enough capacity for transporting and processing camel meat to match the capacities available for beef processing and export (Wellis, 2013).

Meanwhile, China is also implementing various programs to increase its camel population and grow the market share of camel meat, but that is unlikely to deter market penetration of the Australian camel meat into the country. The success of Chinese marketing efforts will also help camel meat from Australia. Given the demographic and social-economic characteristics of China, the best promotion strategies for Australian camel meat would be direct marketing and the use of stakeholders to provide industry-wide support. The opportunities for growing the market are huge and should be tapped.

The market for camel products in China has lasted more than 3000 years, and it continues to show considerable resilience, amid the increasing popularity of meat and other animal products (Wellis, 2013). China is also a notable producer of Camel meat, although its domestic consumption takes up for the country’s entire production capacity.

Until the last few decades, much of the Chinese market has been informal, and it has been difficult for marketers in various interest firms, as well as state authorities to form a thorough description of the market. Nevertheless, there is considerable evidence available from the main camel rearing areas of China, on the existence of a large enough domestic market to warrant interest for international firms dealing with camel meat. This is the main reason why a thought of exporting camel meat from Australia to China would arise.

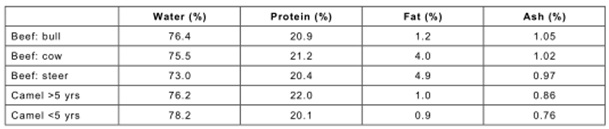

In Australia, camels are used mainly for meat consumed by both humans and pets (Askin, 2011). In China, camel meat is mostly for human consumption. Nutritionally, camel meat has protein levels that match those of beef, but it has less fat content than beef. In addition, the meat is similar to lamb and chicken, but with a significantly reduced fat content, such that it would take eight times the content of camel meat to have similar fat content as chicken and eighteen times of camel meat to match the fat content of pork (Askin, 2011). From the onset, camel meat is suitable for people who are nutritionally conscious and want to limit their fat intake from meat.

This report offers a background of China and Australia camel industries and then evaluates the market demand situation in China for camel meat. It also proposes a strategy for introducing and sustaining an import business for the Australian camel meat in China. To realise this objective, the report uses two key business tools; the marketing mix tools identified by its 4Ps of pricing, promotion, product and place, and the SWOT analysis tool. The latter helps to inform the right strategy for dealing with available opportunities in relation to the limitations that exist due to organisational or business sector weaknesses and threats. The paper then briefly discusses the rationale for introducing camel meat as an export business to China from Australia.

Background of China

This section on China presents an overview of the country under four main factors, namely; economic, cultural, political, and social. These are the factors that will likely affect the orientation of business activity in the country. They also provide a basis for presenting background information about the country, which would be relevant to this report when viewed from a marketing perspective.

Economic

At present, most Chinese businesses are well attuned to the market economic principles of capitalism. However, they still operate within a social fabric where kinship is superior and defines networking exercises. Thus, as a reflection of the Confucian ideology and the Chinese cultural heritage, it would be observed that small and medium enterprises mainly owned by individuals in China, operate very competitively among each other.

However, their market behaviour is detached from larger firms. The smaller firms collaborate, instead of competing with bigger firms, which are mainly SOE. The relationship remains competitive for international multinational firms, showing the lack of connecting social fabric. A common feature of the Chinese firms is that they remain competitive both at home and abroad, sometimes opting to develop their own network of suppliers, affiliates, and distributors (Haley, Haley, & Tan, 2002).

There have been numerous economic reforms in China, led by changes in the government’s policy of the country’s international competitiveness. At the same time, the burden of a socialist economy forced the government to consider market reforms that would allow private enterprises to shoulder some of its burdens.

Some key outcomes of the reforms have been the freeing up of land ownership from the state, although the state still holds power to dictate land-use policy. At the same time, local governments got more power to manage their economic and social affairs without the national government’s interference. At the same time, previous state companies opened up to public ownership, and they formed joint partnerships with foreign firms related to their economic sectors.

As it stands, China has a market-oriented socialist economy, and it provides enough freedom to allow private enterprises to operate within the parameters of the market. The government also allows foreign-owned firms to set shop in China and target the local Chinese population with their products. Despite this, the state still continues with reforms that aim to increase the competitiveness of local firms. However, some of the reforms spark resistance and protests from foreign firms and nations because they could cause unfair advantages.

While reforms identified different areas of modernisation throughout the 90s and 2000s, this report is biased towards reforms in agriculture for use in the subject topic. The state had first to allocate land to households because all the land previously belonged to the government (the people). The next step of agricultural reforms was to permit the sale of surplus produces to markets, which ushered the first economic activities among Chinese living in rural agricultural areas.

The policy of China is to become self-sufficient. The country has achieved its goal in most major agricultural commodities. The growing population is increasingly challenging that position, and the limited nature of the arable land resources is forcing the country to look outside for sustenance. China’s population makes up 20 per cent of the global population, yet the country has only 9 per cent of the global arable land supply and 6 per cent of the global water supply (Coates & Luu, 2012). With the present technologies and knowledge, China cannot meet its demand for meat by only relying on domestic production.

Cultural

The Chinese people are mainly conservative and seek to live in a harmonious way within their society. They mostly subscribe to Confucian principles and have a long-term orientation of life where they are more likely to overlook short-term discomforts and gains, but prefer sticking to long-term plans and historical ways of living.

Religion and political affiliation are two major factors for affiliation and cohesion among the Chinese. Although the unification of the Chinese people was initiated by political ideology, it has been based on economic prosperity over the years.

Political

The Chinese Communist Party began in 1949 and took over the running of government and any state-related functions, such as the provision of ideological and social leadership for the Chinese people. As the party took control of the economy, it initiated various policies that have ensured its hold of the political and economic matters of the country to date. As the government, it has been responsible for the allocation of resources, although that role was later diluted by the introduction of neoliberalism policies in the country. However, the government has played a huge part in identifying suppliers and supply arrangements, as well as the management of sales for products and services offered by state-owned enterprises.

As the government controlled the means of production, it also influenced access to opportunities for its citizens. This is partly the reason why the development levels of different geographical parts of China are not equal. Before neo-liberalisation took off fully in the 90s, many Chinese grew up with, were educated, and then got job allocations that would form their careers with few or non-existent options for change.

The leftist principles are no longer the key influences of the Chinese People’s Party way of governance. However, there are still authoritative undertakings by the government that affect private business and private individuals. For example, governmental bureaucracy and party politics are factors that force even the most market-oriented businesses to resort to lobbying as a way to influence government action. The situation is accelerated by the fact that the government provides various resources that are critical for the survival of firms in the market environment.

Social

The main areas of China that are major consumers of camel meat also have a significant number of the Chinese Muslim population. These areas are Inner Mongolia, Gansu, Ningxia, Qinghai, Xin Jiang, Beijing, Hebei, and Shandong. These are areas in the west and north-west part of China.

Rural areas of China grapple with low-income status and the lack of adequate economic opportunities compared to urban and industrialised areas. They are also prone to social unrest and poverty-related social problems. In 2009, there were reports of riots among the Chinese Muslims in the western part of the country, which is also the main camel producing area (Wu, Chan, & Deng, 2011).

Chinese camel background

As earlier mentioned, the domestication of camels in China has lasted three millenniums. Apart from milk and meat, another main product from camels is fur, and the animals are used for transport. The use of camels as a means of transport was a major reason for the preservation of their population throughout the 15th to 20th century. The modernisation of China brought by its industrialisation also led to the easy availability of other meat and milk sources. Agriculture was a major beneficiary of modernity; unfortunately, the pace of developing commercial production of farm produce for other livestock was faster than that of the camels.

Camels have been relegated to a niche meat source for urban populations, though it continues to serve as the primary meat source in rural areas where there are many camel herding communities. Meanwhile, there have been renewed efforts by the government to increase the camel population by introducing and nurturing camel farming as a large scale agricultural activity. The Chinese government has focused its camel farming reforms in the western part of the country that already has the largest number of camels and shows considerable promise for the growth of the adequate domestic market.

The national government, working together with provincial governments, is establishing state run farms, but they let private enterprise handle management. The involvement of the national government ensures that the project has enough state resources to make it successful, while private business involvement is expected to implement market relevant strategy for sustainability of the venture.

Presently, the Inner Mongolian Provision Government is working towards the mainstreaming of camel production and sells both locally and intentionally. This comes with the realisation of China’s strategic positioning as a potential producer of camel products. The country can gain through a focus on embryo technology, food production, and veterinary technology for camels, which would contribute to a rapid increase in the available camel production enough to support a domestic and export industry for camel products. Other than just camel meat, milk and fur, relevant authorities in China are looking at creating tourism attraction activities, with camel racing as the main activity.

A key hurdle for the Chinese is the successful marketing of camel products as a potential replacement for pork, beef, chicken, and lamb. A lot has to happen in the camel production ecosystem in China to succeed in its ambitious project. For example, there is a need to increase grassland vegetation and protect it to provide adequate pasture for camels. The industry is also not functioning well; thus, there is a need for developing production and distribution centres and incentives to attract private enterprises. In addition, there should be product developments and value addition activities under camel production to make the product superior, as both medicine and food.

The farming community will also need to be sensitized about the benefits of camel products as an incentive to be more proactive in their production efforts. In this regard, scientific research on camel development and market awareness initiatives are identified as the main solutions. Relevant authorities, such as the Inner Mongolian Province government are working towards the realisation of policies that will grow the Camel industry.

Chinese market demand

As already stated, the market for camel meat in China is declining, unless interventions will pay off in the near future. Camel feet have a higher demand than camel body meat. The price of camel meat is low when compared to other meats. It would be expected that a lower price would spur demand, but many Chinese consumers prefer other meat, partly due to their exposure to alternative cuisines from abroad.

Other than restricted geographical production zones for camel meat and milk, the consumption of the product in China also follows the concentration of the Chinese Muslim population. In addition, the domestic prices of the product are influenced by the disposable incomes of the population in the main areas of production. The marginalisation of the western part of China has contributed partially to the inferiority of camel meat as a cuisine. People migrating to the developed parts of China from rural areas are quick to denounce the rural behaviour by adopting new norms. Unfortunately, part of that has been the consumption of less camel meat, even though such persons would serve as a viable target market for the product.

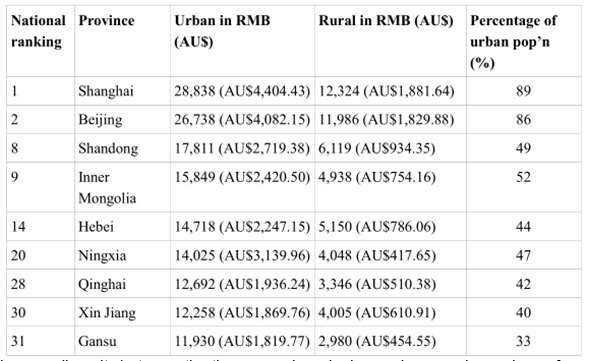

The following table breaks down the disposable incomes of the native Chinese populations in different regions to provide an overview of the potential markets for camel products as they currently are and premium products, which would appeal to higher earning individuals.

The income disparity between the three camel producing and consuming regions of Qinghai, Xin Jiang and Gansu when compared to the economic active areas of Shanghai and Beijing is significant.

China is a net meat importer. The country imported meat worth USD 2.2 billion in 2010. Most of the meat came from Brazil, the United States, and Denmark. Australia is the second largest supplier of frozen beef to China after Brazil and its grain fed beef dominates the premium end of the Chinese market (New Zealand Trade & Enterprise, 2012).

China has a high rate of camel slaughter. With present rates, its population of camels will continue to decline faster. The country is also not importing camels to sustain its 30.4 per cent slaughtering rate (Kadim, 2013).

Market drivers

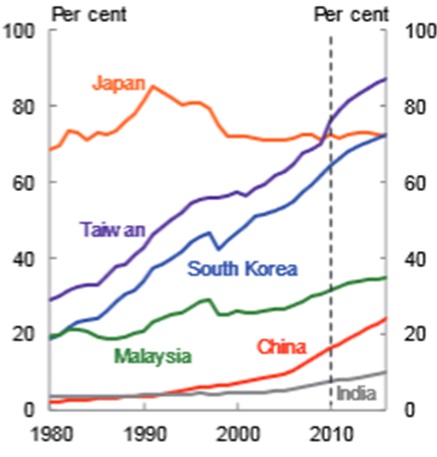

Urbanisation has created adequate markets for imported food. In the 1990s, only 25 per cent of the population in China was urbanized, but the figure is likely to jump to 75 per cent by the year 2015, with most urban dwellers exhibiting characteristics of middle class income earners, such as varied dietary preferences and shopping outlooks (Hamshere et al., 2014). The GDP growth of China remained steady, with a double digit growth. The following graph shows how the rise of per capita incomes compared with other countries.

Marketing mix, the 4Ps marketing strategy

The aim of the marketing mix strategy is to have the correct product and place correctly in the market. This means that the product should be sold at the right price and at the right time. Thus, everything done under the marketing mix aims to realise this objective. The four parts of the objective, price, promotion, place, and the product also form the four areas of review to ensure that everything happens as planned and the market capturing endeavour is a success.

Price

In China, camel meat sells for 20 Yuan a kilo and camel feet sells for 25 Yuan a kilo, which translates to about AUD 3 and AUD 3.8 respectively. In comparison, the Australian beef exported to China sells for AUD 24 to AUD 463 a kilo, depending on the cut and location of sale (Wu, Chan, & Deng, 2011). Lamb goes for AUD 5.9 to AUD 5.23, while Kangaroo meat goes for AUD 4.2 to 6.7 per kilo (Wu, Chan, & Deng, 2011). On the other hand local prices for local meat sources are as follows: Beef sells for about AUD 5.3, while lamb sells for approximately AUD 6 (Wu, Chan, & Deng, 2011).

Price trends for the past half-decade show a steady rise of 40 per cent, which is expected to persist throughout the current decade because of a number of factors. The price increase in imported Australian meat products in China mimics price increase in domestically produced meat in China, whose upward price trend has been in tandem with the rapid growth of the Chinese economy. The key indicator of price increase prospects is the increase in disposable incomes of people in China and the overall increase in the number of the middle class population, which is the main consumer.

Camel milk sells for between AUD 2.3 to AUD 4.6 in the Xin Jiang Province. The difference is caused by supply constraints arising out of the limited number of camels producing milk in the region. This is also an indication of the lack of adequate distribution infrastructure that would eliminate the shortages and ensure that the price remains even.

Despite the overly low prices for camel meat, the camel hump, which is a special delicacy, still manages to attract premium prices and high-class restaurant treatment, thanks to its significance to the Chinese cultural heritage (Wu, Chan, & Deng, 2011). This is also an indication of possible niche market segments that the Australian exporters of camel meat to China can consider exploiting, with the hump or an alternative camel product.

Product

Local camel milk and meat undergoes limited processing before it is offered for sale in the Chinese farm markets. However, when sold in upmarket areas, such as supermarkets, much of the product is offered in a packaged way, with minimal processing done to make it ready for consumption or to increase its shelf life. The Chinese are also fond of camel bump, mainly served in Chinese banquets. For ordinary consumption, consumers can only obtain the camel hump from top-class restaurants at an expensive price tag.

According to the Australian Trade Commission (2014), processed foods and wine from Australia have better entry terms of the Chinese market compared to other agribusiness products. On the other hand, for the export business to succeed there is a need for a stable supply of camels to serve the potential growth of the market. Commercial farming of camels in Australia may be considered at some point. Most of the meat exported will be in carcass form and in cut pieces ready for consumption.

Promotion

Traditionally, the consumption of camel meat has been a less frequent affair among the Chinese people, even those who are the most prominent consumers. For the current consumers, both in rural and urban areas, a number of factors affect their consumption patterns. Preferential patterns among the Chinese consumers show that camel meat consumption has been on the decline. As of 2010, camel meat combined with other exotic meat registered a consumption level of 1 million tons, while the other three main meats recorded considerable consumption levels. According to the 2010 data, pork is the most consumed meat and its popularity is about fifty times that of the camel and exotic meat category (Wu, Chan, & Deng, 2011).

As earlier explained, many rural to urban migrants quickly stop taking camel meat because of its association with low income earners. On the other hand, other consumers located in non-camel producing areas of China associate camel meat to the west and north-west side of China. Unfortunately, the association also prompts them to only consider the product when they are travelling to those areas. Meanwhile, wealthy consumers will gladly take on the hump, but that only constitutes a minority of the total number of both consumers and consumption levels of camel meat.

As it stands, based on the overall discussion of this report and the facts presented here, there is an urgent need for sensitisation. Most of the marketing activities for promoting the Australian camel meat will not succeed if the demand for domestically produced camel meat does not increase. The two markets are tied by the fact that a successful promotion of the domestic market will make an import market relevant and validate the charging of premium prices for the imported camel meat. It is only logical for international stakeholders from Australia to join them in various ventures to ensure they succeed together in nurturing the market, given that the Chinese local authorities are already addressing the public awareness issue.

Henceforth, the introduction of the Australian camel meat to the Chinese should be viewed a novice product entry in a young market lacking adequate structures. Key attractions of the Australian camel meat in China will be high quality production and packaging using modern standards and features and convenience for use by the Chinese consumers.

There will be a need to increase the confidence of consumers so that they treat camel meat with the same high level confidence they show for other food and beverage productions imported from Australia, mainly for their food safety and ingredient characteristics. High quality and freshness would be additional advantages for the Australian camel meat (Australian Trade Commission, 2014). Promoting the origin of camel meat imported from Australia will help to form a high quality association of the product and, possibly, stimulate demand.

Australia has a high reputation of food processing, especially beef, with adequate regulation for the safety of meat and meat products, both at the national level and at specific state levels. These features would be put in packaging to inform ordinary consumers about the product value proposition. Packaging is also supposed to be very different, visibly to prevent wrong association with inferior products available in the market (Wu, Chan, & Deng, 2011).

Promotion will involve the Australian and Chinese government authorities working on trade and camel meat marketing. It will also rely on specific businesses exporting camel meat to China. The businesses may form joint ventures with local companies for the sake of market knowledge sharing. The collaborations will ensure adequate focus is put on the imported product through an adequate distributorship to all mainstream retail outlets in the target cities, which should then grow to cover the entire country. Premium placement on retail shelves and the use of in-store advertising will help. Advertising in mainstream media and social media engagement will also work for branded camel meat from Australia. Direct marketing efforts would be employed on large scale buyers, such as restaurants or repackaging businesses.

Place

A potential target for imported meat coming from Australia would be the current geographical regions with the most Chinese consumers, which are western and north-western parts of the country. Although these regions have high populations of Chinese Muslim, a fact that has contributed to their high consumption of camel meat, they also have large numbers of non-Muslim consumers. The intercultural and religious coexistence has promoted the overall consumption and a rise in camels’ products and camels respectively.

The highly urban areas of China are also good targets, mainly due to the concentration of middle income earners in these regions. They have the necessary disposable income levels that would support an import market for camel meat. High urban population densities in the country also make the cost per individual low compared to rural areas. It makes better business sense to place billboards and other above fold promotion materials in urban areas because of this reason and the availability of the native promotional service businesses that are best poised to come up with specific market targeting strategies for the country (Ferrell & Hartline, 2011).

The best places to undertake marketing efforts would be at stakeholder sponsored events because there is a pertinent need for involving industry stakeholders in the marketing of camel meat in China. With enough sensitisation of the groups responsible for rebuilding the popularity of camel meat in China, there would be a high chance of having adequate business and regulatory authority focusing on the industry. This should contribute to its rapid growth. For example, targeting the Australia-China trade conferences and workshops would ensure that some positive resolutions on trade between the two countries benefit camel meat export business.

Rationale for camel meat export to China from Australia

China is experiencing a surge in its demand for protein, and has become dependent on foreign beef to satisfy its demand for camel meat. On the other hand, Australia exports 80 per cent of its beef and has a mature export industry for meat whose principles and infrastructure would help to promote camel meat exports. In addition, the two countries, Australia and China are working on a preferential market access agreement that would see goods from Australia face fewer legal and market entry restrictions in China (Binsted, 2014).

The economic development of China coincides with rapid urbanisation, similar to what other industrialized economies went through during their development phase. The trend explains the rapid rise in urban population incomes and constant migration to cities and industrial centres, where the labour demand is high (Coates & Luu, 2012).

A combination of the rising meat prices in China, signified by the five times increase in price of beef since 2000, and the rising demand whose current levels are four times what they were in 2012 are indications of export numbers that could be achieved when strategies used in the beef export industry are applied to the camel export segment from Australia to China (Binsted, 2014).

Feral camels in Australia are sometimes considered as a nuisance because of their classification as pests, but the export of their meat to China or any other country solves the problem of their nuisance (Brindal, 2011). According to a report by Jooste (2014), Camels from Australia are among the best in the world because of their disease free nature. Unfortunately, as demand rises, the supply may not be able to catch up because the effects of a culling exercise initiated by the government at a cost of AUD 19 million have been devastating to the overall camel population in Australia (Jooste, 2014).

While the camel export industry is expected to benefit from the already developed beef exporting infrastructure, such as the available export abattoirs, more work will be needed to make the facilities fit camel processing. In Australia, ferrying of camels is one of the most costly activities within the value chain and most of the country’s camels come from its southern parts. Camel carcass weight varies with the age of the camel and sex, and can be as high as 236 kg or as low as 150 kg for mature camels after dressing (Salehi et al., 2013). Camel meat is a valid alternative to beef when used for human consumption or pet food as indicated by the table below, which depicts the similarity in nutrition content. An attractive point for the meat would also be its low fat content (Zeng & McGregor, 2008).

SWOT Analysis of the Chinese market

Strengths

The Australia China Corporation already exists to manage trade relationships between the two countries and serves as the exclusive agent for dealing with camel meat. In China, it provides high quality export camel carcasses that have undergone excellent vacuum packing procedures. Having a presence in China and dealing with camel meat puts the corporation in a suitable position to advise relevant government and trade authorities on the best way to penetrate and develop the Chinese market for Australian camel meat (Australia China Corporation, 2014).

Weakness

Beef is a popular meat in China, at both basic and premium food markets. Dethroning it from the most preferred protein source will be a tough thing to do. In fact, the popularity of beef has even attracted unscrupulous business activities of selling fake beef made from processed pork. In 2013, China had a case of businesses that sold fake meat that was created through paraffin and industrial salt treatment of pork. Consumers were fooled and would have ended up paying beef prices for 22 tons of pork meat that was seized (Mosbaugh, 2013). The scandal highlights the laxity in law enforcement concerning traceability and food safety. However, it also serves as a motivating factor for the Chinese authorities to pay keen attention on meat being imported into the county.

Opportunities

China will still remain Australia’s largest trading partner for several coming years. The two countries have a favourable investment relationship (KPMG, 2011).

There is a significant community of the Chinese people living in Australia. In 2009, there were 320,000 people from China in Australia. According to the 2011 Census, China is the third largest contributor of the Australian population after the UK and New Zealand (ABS, 2012). The population can play a critical role in cementing relationships between small and medium enterprises in the two countries to facilitate successful marketing and export of Australian camel meat to China.

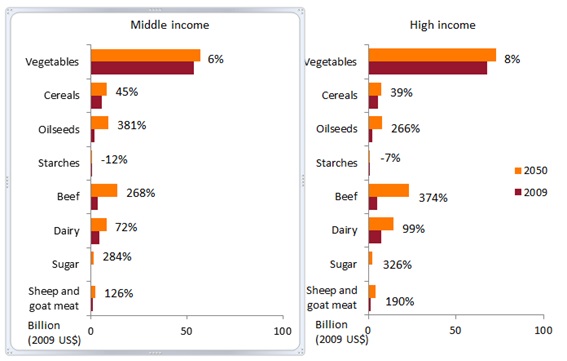

China’s food consumption by value will have increased by 104 per cent between 2009 and 2050 (Hamshere et al., 2014). Much of the demand will be on non-starchy staples, which provide high value dietary utility. Meat is one of the major foods under the high value foods category. Growth in demand will be in tandem with the growth of urban populations and the increase in the middle income status of most households. Although actual figures for camel meat demand projections are unavailable, the expected rise in overall meat demand provides a mirror for reviewing the expected increase in demand for camel meat, as long as government and private sector plans for market sensitisation and commercial farming are fruitful.

The following graph shows a comparison of middle income households and high income households in China, in terms of existing and future agricultural commodities demand (Hamshere et al., 2014). Notably, sheep and goat meat, which are close to the classification of other meat where camel meat falls, register considerable growth in demand in both middle income and high income households.

The value of meat across all categories will also be increasing in the coming years, with differing percentages depending on the popularity of the meat. Imports will continue to play an important role in meeting consumption increases in China for meat, other than poultry and pork, where domestic production matches the country’s consumption levels (Hamshere et al., 2014).

Threats

The country has an unpredictable business environment, partly caused by the authoritative nature of the government. The country’s legal system is also opaque and subjective. Businesses, especially foreign owned, cannot always look forward to consistent implementation of the law. In addition, China does not fully protect intellectual property and most foreign companies setting shop in the country must first access the risk exposure and have a robust mitigation plan.

Conclusion

The main attractive points for exporting camel meat to China are the growing Chinese population, the increase in income status of most Chinese households, and the existence of favourable economic and social environments for doing business in China. These factors play an active role in increasing the demand for camel meat and the projected increase is unlikely to be met by domestic production.

The present sensitisation efforts by the Chinese authorities will increase the market demand for camel meat and most rural populations of camel producing regions in China will benefit from the availability of a market. It is the same fate that awaits the Australian camel meat exporters, who have been working on mechanisms to make the sector lucrative and provide a sustainable income source for rural Australian populations in the last half a decade.

Some hurdles need to be overcome, such as beating an unpredictable business environment of China, and increasing demand of camel meat to match the high demand for beef and other meat in China. In this regard, the Australian camel meat has a high chance of penetrating the Chinese market when it is offered as a premium product targeted at high income households and individuals. High margins would then make economic sense for increased market spending to grow demand and sustain the business. Working with trade authorities in both China and Australia to establish favourable importation policies for Australian camel meat going to China would play a significant part in making the business sustainable and rewarding to both countries.

References

ABS. (2012). Reflecting a nation: Stories from the 2011 Census, 2012–2013.Australian Bureau of Statistics. Web.

Askin, P. (2011). Camel meat could become newest Australia export.Reuters. Web.

Australia China Corporation. (2014). Australia camel meat. Web.

Australian Trade Commission. (2014). Food and beverage to China. Web.

Binsted, T. (2014). Australia poised to benefit from China’s beef demand.The Sydeny Morning Herald. Web.

Brindal, R. (2011). Camel meat exports aim to turn pest into profit.The Wall Street Journal. Web.

Coates, B., & Luu, N. (2012). China’s emergence in global commodity markets. Langton, Cresent: The Australian Treasury.

Ferrell, O. C., & Hartline, M. (2011). Marketing strategy (6th ed.). Mason, OH: South-Western, Cengage Learning.

Haley, G. T., Haley, U. C., & Tan, C. (2002). New Asian emperors: The business strategies of the overseas Chinese. London: John Wiley & Sons.

Hamshere, P., Sheng, Y., Moir, B., Syed, F., & Gunning-Trant, C. (2014). What China wants: Analysis of China’s food demand to 2050. Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry. Canberra: Australia Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics and Sciences.

IMF. (2012). World Economic Outlook. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund.

Jooste, J. (2014). Trade of wild camels to South Korea zoo the catalyst for more exports.ABC Rural. Web.

Kadim, I. T. (Ed.). (2013). Camel meat and meat products. London: CABI.

KPMG. (2011). Australia & China: Future partnerships. Sydney: The University of Sydney China Studies Center.

Mosbaugh, E. (2013). 22 tons of fake beef seized in China. First We Feast. Web.

New Zealand Trade & Enterprise. (2012). Food and beverage in China: Market profile. Auckland: New Zealand Trade & Enterprise.

Salehi, M., Mirhadil, A., Ghafouri-Kesbi, F., Fozi, M. A., & Babak, A. (2013). An evaluation of live weight, carcass and hide characteristics in Dromedary vs. Backtrian x Dromedary crossbred camels. Journal of Agricultal Science and Technology, 15, 1121-1131.

Wellis, B. (2013). South Australia looking at camel exports.The Advertiser. Web.

Wu, D., Chan, C.-H., & Deng, C. (2011). Australian Camel Meat: China market. East Brisbane: Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation.

Zeng, B., & McGregor, M. (2008). Review of commercial options for management of feral camels. In Managing the impacts of feral camels in Australia: a new way of doing business (pp. 225-272). Alice Springs: Desert Knowledge CRC.