Finding a balance between development and sustainability has been an objective many people find difficult to attain. The use of resources has been intensifying annually due to the increasing population and people’s growing demand. The fashion industry is now seen as one of the most vivid illustrations of unreasonable use of resources (Bick, Halsey and Ekenga, 2018). Fast fashion can be referred to as “a business model based on offering consumers frequent novelty in the form of low-priced, trend-led products” (Niinimäki et al., 2020, p. 189). On the one hand, this model has enabled millions of people to access more clothes that are more affordable. On the other hand, adverse environmental and social impact has been substantial as well. Due to the shift towards more sustainable business practices, the fast fashion industry is also undergoing certain changes. This paper includes a brief analysis of the ways to address consumers’ fashion-related needs and reduce the negative environmental impact of the fast industry.

Fast Fashion and Its Environmental Footprint

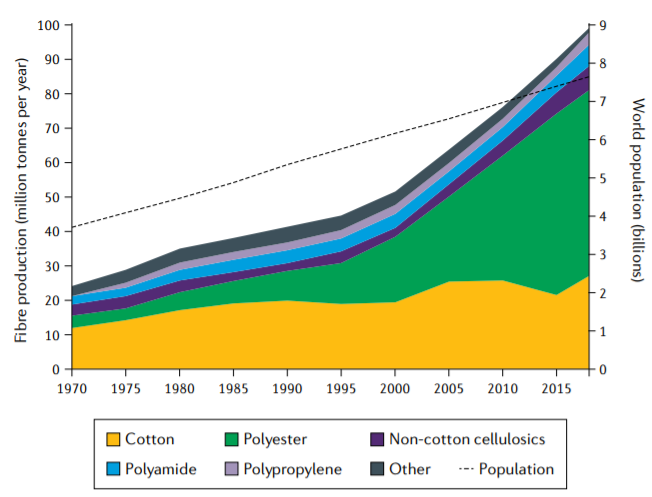

To some people, the fashion industry may seem rather irrelevant compared to such traditional giants as the oil industry, but the former has a considerable share in the global market. It has been estimated that the value of the world’s fashion industry is approximately 3,000 billion dollars, which is over 2% of the global Gross Domestic Product (GDP) (Shirvanimoghaddam et al., 2020). The consumption of textile goods has almost doubled during the past two decades and reached 13kg per individual or 100 million tons annually (see Figure 1).

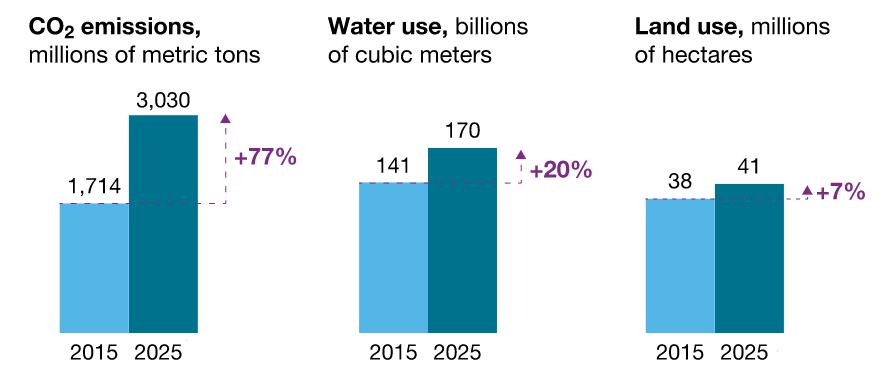

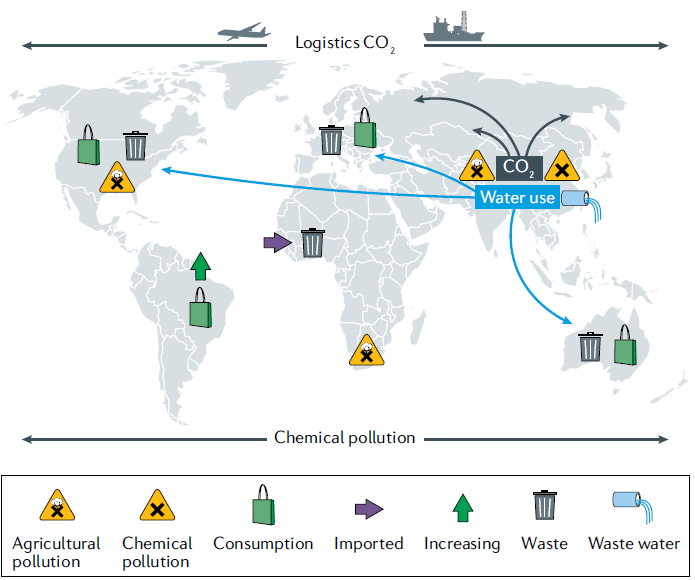

Such significant growth comes at a price that is mainly associated with a tremendous effect on the environment (see Figure 2). For instance, Shirvanimoghaddam et al. (2020) stress that only 15% of the wastes are recycled. It is noteworthy that developing countries are more vulnerable since a considerable portion of the used textile is a part of the second-hand clothing trade (Bick, Halsey and Ekenga, 2018). For example, over 500,000 tons of used textile goods are exported from the USA (Bick, Halsey and Ekenga, 2018).

Recycling mainly occurs in western countries, which makes the environmental burden of developing countries more pronounced (see Figure 2). In addition to the contamination of vast territories used as landfills, fast fashion wastes often penetrate into diverse ecosystems due to inadequate waste management (Mehta, 2019). Textiles produced of low-quality components contaminate the ocean and suburban areas. Since a considerable part of production facilities is located in developing countries, these areas are affected most. The governments of these countries tend to place a lower value on ecological problems, which leads to undesirable effects.

In addition to the environmental impact, the fast fashion industry is closely linked to the consumerism culture that is still prevalent in the world (Niinimäki et al., 2020). According to the social practice theory that is a social theory focusing on the human society and its peculiarities, things are seen as an indispensable part of human existence (Reckwitz, 2002). Things have become something more than objects used to satisfy individuals’ needs. People see things as “objects of the knowing subject” and “constitutive elements of forms of behaviour” (Reckwitz, 2002, p. 253). In simple terms, things have an influence on people’s behavior, and fast fashion can illustrate this process. Many people find it critical to wear fashionable things to be a part of a group (sub-culture) or express themselves (Barnes and Lea-Greenwood, 2018). Others want to buy new things for the sake of acquiring a new thing or in the course of socializing (Afaneh, 2020). Fast fashion offers numerous ways to satisfy people’s needs and make them feel members of a larger community.

E-commerce has contributed to the growth of unsustainable behaviors as purchasing has become even easier and more affordable (Niinimäki et al., 2020). People are enticed to buy more as they can save more (and buy more) without even leaving their homes. The COVID-19 pandemics contributed to the increase in online sales. Niinimäki et al. (2020) emphasize that this business model is even less environmentally sustainable due to the peculiarities of logistics. Container boat transportation typical of traditional retailing is replaced by air cargo in e-commerce, so the environmental footprint is more significant.

Shifts in Public Opinion and Growing Role of CSR

Although the human society is still characterized by the focus on consumerism, people are becoming more responsible. Consumers start being more environmentally conscious and try to reduce their negative influence on the environment (Javed et al., 2020). The rise of the corporate social responsibility approach can be seen as companies’ response to this trend. Manufacturers try to develop sustainable ways to produce goods, reduce natural resources consumption, and introduce recycling incentives. C&A is one of the leaders in adopting sustainable practices in the industry (see Figure 3). The third of the garments the company sells can be referred to as eco-friendly goods (Sustainable fashion, 2020). The retailer claims that they focus on the production of garments of recyclable cotton and try to adopt a holistic approach to the production process in order to ensure the reduction of CO2 emissions and proper waste management (C&A, n.d.).

H&M initiated several projects aimed at reducing its wastes. In addition to second-hand sales and the promotion of more durable fashion, H&M developed the concept of recyclable jeans (Mehta, 2019). The company utilizes natural components to produce jeans and accessories that are easily recyclable. Another fast fashion leader in the global market, GAP, has also expressed its intention to move to a circular industry (Mehta, 2019). The two large textile producers show their commitment to sustainable practices, which resonates with the overall attitudes to the matter in different countries.

Governmental Effort and Its Relevance

It is necessary to add that, along with companies’ willingness to build positive images and adopt CSR strategies, regulations imposed by national governments and international institutions encourage businesses to employ sustainable approaches. These efforts are instrumental in setting the minimum level of CSR activities necessary to improve environmental sustainability and offering directions to move for further development (Mehta, 2019). The primary areas covered within the scope of these efforts include CO2 emissions reduction, recycling, waste management, and resource consumption.

Some of these initiatives include the provision of financial support and tax reduction to high-achievers in dropping the levels of CO2 emissions (Niinimäki et al., 2020). The EU government is introducing diverse regulations concerning waste management, forcing and encouraging companies to recycle instead of bringing their wastes to landfills (Wang et al., 2020). It is important to note that European countries display different approaches and commitment to environmental sustainability. Such countries as Germany, Norway, and Finland have progressed considerably, while less wealthy states lag behind. Trade policies established by the USA are aimed at ensuring global equity (Bick, Halsey and Ekenga, 2018). Such regulations impose restrictions related to importing and exporting used textiles. Companies are encouraged or directly forced to donate to the projects aimed at the development of recyclable industry and similar initiatives (Mehta, 2019).

Interventions Needed

Further steps in the areas mentioned above are necessary for the minimization of the negative effect of the fast fashion industry. The standards existing in the western world are quite appropriate and under proper review each year (Bick, Halsey and Ekenga, 2018; Mehta, 2019; Wang et al., 2020). In addition to various strict regulations regarding CO2 emissions and waste management, the UK government, for instance, has the Sustainable Clothing Action Plan for fast-fashion companies to follow (Abdulla, 2019). This voluntary plan of action encourages companies to join in and suggest their strategies to comply with the existing and upcoming standards. Numerous retailers and fashion industry leaders tend to join the initiative, which positively affects their overall image and gives an opportunity to contribute to the development of sustainable practices for the entire industry.

The UAE can become a major advocate of sustainable practices for the development of the region. The country posed a number of KPIs to be reached by 2021 regarding waste management, emission reduction, and other environmental aspects. Some of the 2021 environmental targets include the improvement of the portion of treated waste of total waste generated (Environment and government agenda, 2020). It also aims at reducing the consumption of non-sustainable energy, as well as decreasing CO2 emissions. However, there are no specific restrictions on the fashion industry. Moreover, the policies tend to be confined to the exact practices of companies without paying sufficient attention to the activities of their partners, which has become a norm in the EU countries.

The introduction of new restrictions rather problematic as businesses oppose such laws and try to shape the politicians’ agenda in different ways. Many laws and norms are regarded as unnecessary and harmful restrictions imposed by irresponsible politicians trying to win votes (Abdullah, 2019). Educating the public about potential hazards and possible ways to mitigate the negative consequences can be instrumental in achieving the consensus in the society (Afaneh, 2020).

The provision of direct financial support can also become an effective strategy governments can utilize to make the fast fashion industry more circular. Small and medium-sized companies are facing significant issues related to the COVID-19 pandemics (Brydges and Hanlon, 2020). The situation related to the pandemics can serve as the basis for the promotional campaigns popularizing sustainability. It is possible to emphasize that humans are vulnerable to numerous global challenges, while sustainable practices are key to the successful development of the society.

Large retailers and manufacturers tend to set new standards and norms accepted by consumers. For example, H&M, in collaboration with other fast fashion companies, has launched initiatives aimed at the reduction of their environmental impact (Javed et al., 2020; Mehta, 2019). Such incentives should obtain governmental support that can be manifested in financial or educational aspects. American officials can also promote such initiatives through international platforms such as the World Trade Organization or other institutions.

Barriers to Implementation and Steps to Undertake

Although the benefits of such efforts can hardly be overestimated, governments can be reluctant to be involved in such incentives. As mentioned above, financial constraints countries have to face make environmental issues seem less relevant and urgent. Activists should ensure that the most urgent ecological topics are discussed in the society, which will make countries address them. Consumers can also become less concentrated on environmental issues due to their financial issues (Afaneh, 2020).

Activists and governments should pay much attention to raising people’s awareness of the economic burden of less sustainable practices in the long run. Social media have been utilized effectively to discuss numerous issues and encourage people to take a particular action. Such incentives as H&M’s online second-hand platform and such products as recyclable jeans should receive high publicity facilitated by the governmental support (Mehta, 2019). Being sustainable should be synonymous with being competitive, and governments can help businesses see the exact paths to achieve competitive advantages based on environmental aspects.

Conclusion

On balance, societies are becoming increasingly aware of environmental issues and willing to adhere to sustainable practices. Durability and recyclability are seen as more relevant in the modern societies. Governments try to develop regulations and standards, facilitating the changes and shifts towards environmentally friendly behaviors. Although these trends are more pronounced in developed countries, developing states are also integrated into the process of this transformation. However, numerous barriers to the implementation of projects aimed at establishing sustainable norms are apparent. Global financial issues can be regarded as major reasons for the slowdown in changes. Nevertheless, governments, companies, activists, and the public should remain in close contact in their effort to create a more sustainable fast fashion industry. Numerous incentives launched in different countries and regions show that governments can contribute to a gradual shift towards sustainable industries.

References

Abdullah, H. (2019) ‘UK government outlines steps to fix fast fashion’, Just-Style. Web.

Afaneh, S. (2020) ‘I can’t quit fast fashion as a student, but I can change how I shop’, Lifestyle. Web.

Barnes, L. and Lea-Greenwood, G. (2018) ‘Pre-loved? Analysing the Dubai luxe resale market’, in Ryding, D., Henninger, C. E. and Cano, M. B. (eds.) Vintage luxury fashion: exploring the rise of the secondhand clothing trade. London: England, pp. 63–78.

Bick, R., Halsey, E. and Ekenga, C. (2018) ‘The global environmental injustice of fast fashion’, Environmental Health, 17(1), pp. 92-95.

Brydges, T. and Hanlon, M. (2020) ‘Garment worker rights and the fashion industry’s response to COVID-19’, Dialogues in Human Geography, 10(2), pp. 195-198.

C&A (n.d.) ‘Our vision: making sustainable fashion the new normal’. Web.

Environment and government agenda(2020). Web.

Javed, T., Yang, J., Gul Gilal, W. and Gul Gilal, N. (2020) ‘The sustainability claims’ impact on the consumer’s green perception and behavioral intention: a case study of H&M’, Advances in Management & Applied Economics, 10(2), pp. 1-22.

Mehta, A. (2019) ‘Beyond recycling: putting the brakes on fast fashion’, Reuters Events. Web.

Niinimäki, K., Peters, G., Dahlbo, H., Perry, P., Rissanen, T. and Gwilt, A. (2020) ‘The environmental price of fast fashion’, Nature Reviews Earth & Environment, 1(4), pp. 189-200.

Reckwitz, A. (2002) ‘Toward a theory of social practices: A development in culturalist theorizing’, European Journal of Social Theory, 5(2), pp. 243-263.

Remy, N., Speelman, E. and Swartz, S. (2016) ‘Style that’s sustainable: a new fast-fashion formula’, McKinsey & Company. Web.

Shirvanimoghaddam, K., Motamed, B., Ramakrishna, S. and Naebe, M. (2020) ‘Death by waste: fashion and textile circular economy case’, Science of the Total Environment, 718, pp. 1-10.

Sustainable fashion: how are the leaders in fast fashion doing? (2020). Web.

Wang, D., Tang, Y. T., Long, G., Higgitt, D., He, J. and Robinson, D. (2020) ‘Future improvements on performance of an EU landfill directive driven municipal solid waste management for a city in England’, Waste Management, 102, pp. 452-463.