Introduction

Following the recent murder and break-in at Frank Aborio’s apartment, the NSW Police department asked Deakin Forensic Unit to help determine the culprits from the suspects in the murder case. Evidence collected from the crime scene included several beer bottles, visible footprints, an unfilled canister of accelerant, and some items thought to have both blood and fingerprints. The NSW Police department asked to determine the likely source of the fingerprint and drug sources.

Fingerprint lifting and characterization were a crucial part of the investigation to be able to make out the culprit. The basis of Fingerprinting is that every human being has a unique design of tiny elevated ridges on the inner surface of the hands known as ‘friction ridge skin.’ The basic steps of carrying out fingerprinting involve lifting the prints from the evidence, identifying the pattern, and comparing with the patterns in the profiles of the suspects. Fingerprint lifting was done to evidence number 15 (Accelerant tin can), and evidence number 16 (novel pages).

Presumptive tests were necessary in this case for identity purposes because drugs were part of the evidence provided. Presumptive tests are speedy tests carried out in order to determine the probable identity of a substance. The majority of presumptive tests involve observing for color changes during the reaction. However, presumptive tests are not precise and can yield a false positive outcome. A confirmatory test, therefore, needs to spell out the identity of a material (Presumptive vs confirmatory tests 2012).

The advantage of presumptive tests is that they help in time-saving. They save time because they give a vague possibility of what a substance could be. This in turn makes it easier to determine the specific identity of a substance later using standard procedures. An ideal presumptive test is fast and inexpensive. It should be able to give a scientist a rough idea of the probable identity of a substance without him/her incurring heavy expenses. The logic of this is that the scientist would still have to carry out a confirmatory test to find the actual identity of a substance.

Results

Part 1: Using flour magnetic dusting powders to develop invisible prints

Part 2: Lifting of fingerprints

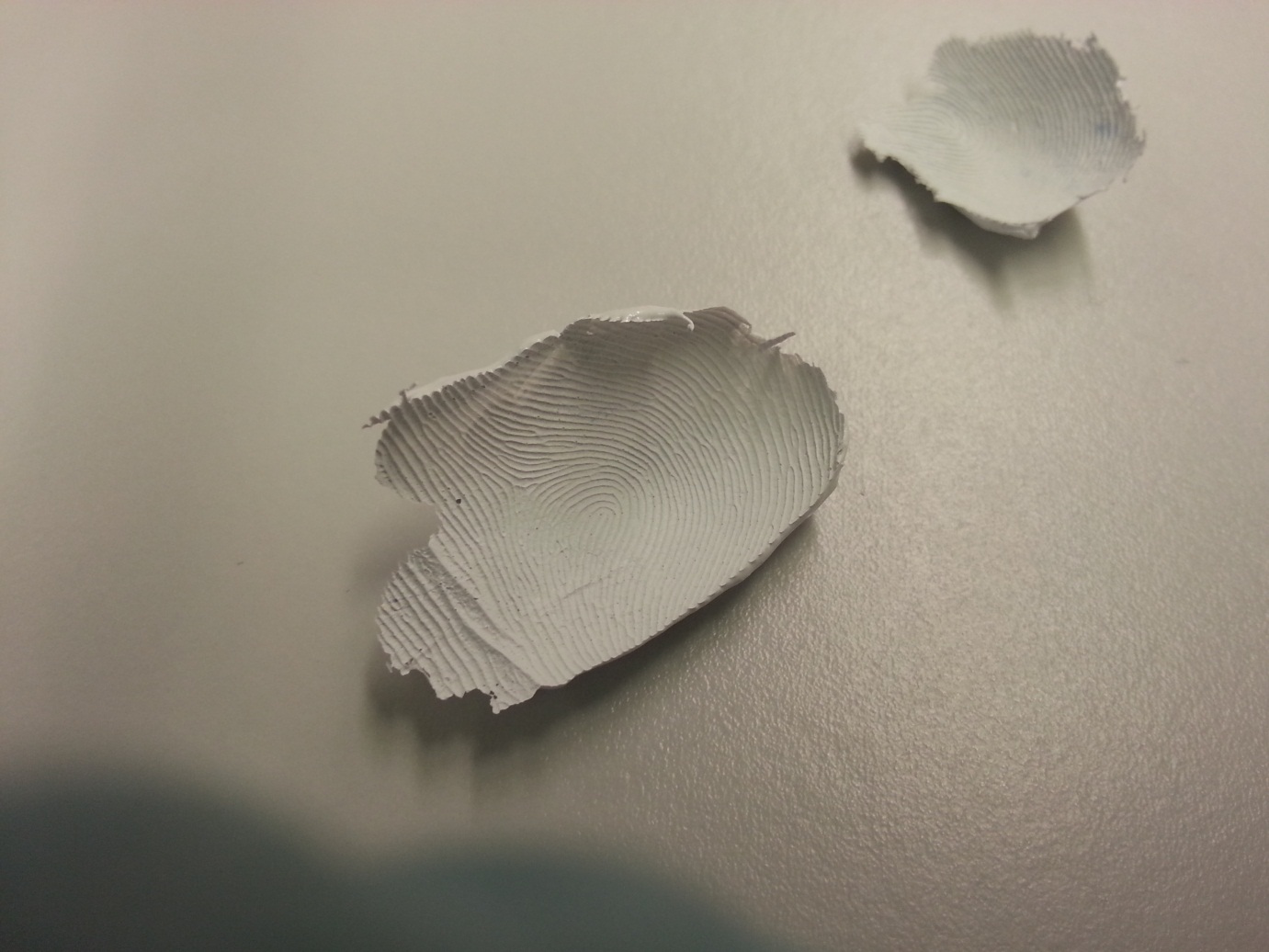

Lifting of fingerprints was done using two methods: tape lifting and mikrosil casting.

Part 3: Characterizing fingerprints on real evidence

The lifted fingerprints were compared to those present on the real evidence: the empty accelerant tin and novel pages.

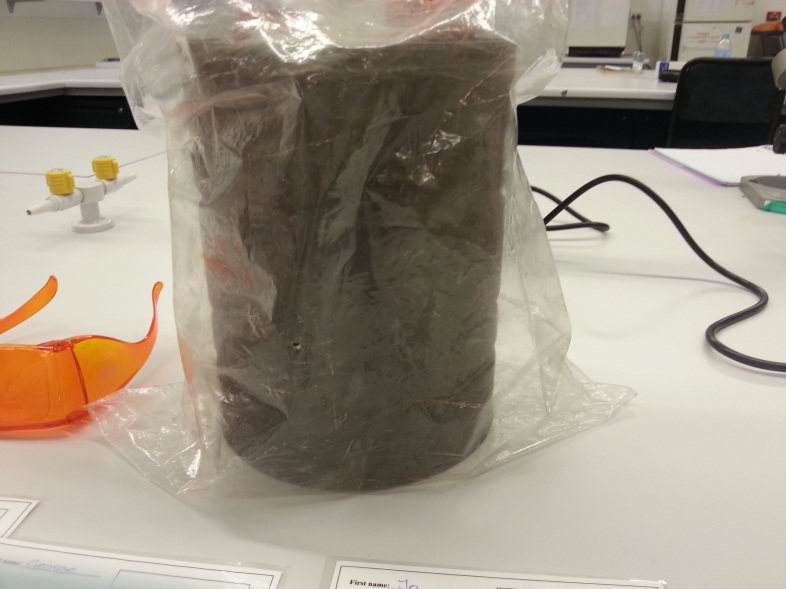

Evidence#15: Accelerant tin

The picture below shows the accelerator tin without fingerprints.

There were no fingerprints on the accelerator tin hence there was no comparison.

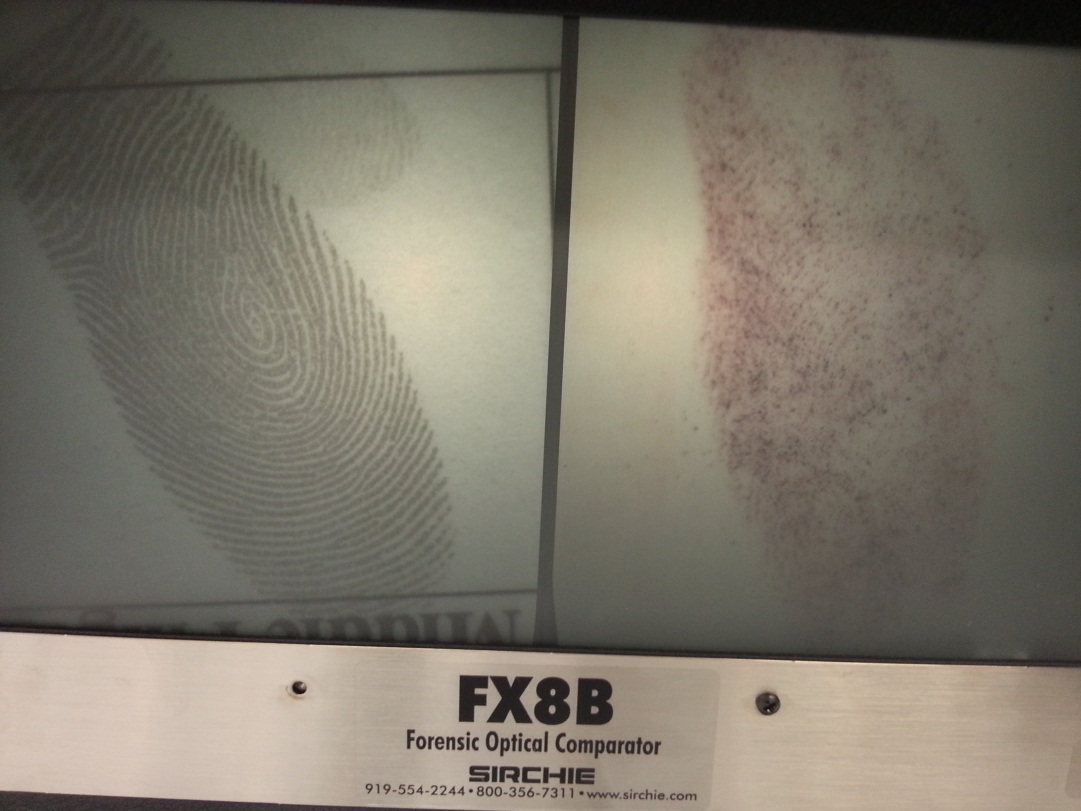

Evidence# 16: Pages from the novel

The picture above shows marching fingerprints on the novel and the collected sample using a forensic optical comparator. Several burned novel pages had fingerprints over them. After comparison with all suspects’ fingerprints, it had been concluded that they turned out to be those of Lindelle Hodge’s middle finger patterns.

Discussion

The development of fingerprints using the powdering method happens through a special bond of powder fragments to the ridges, with the background areas having a low affinity for the fragments (“Powders for fingerprint development” 2010, p.194). This implies that the powdering method should be used only in nonstick faces where there are no impurities or contaminants. If contaminants are present, the powder will not be able to distinguish the ridges and will end up sticking to the entire surface. Shapes of particles, chemical properties of the powder and electrostatic forces are some of the aspects that are speculated to promote sticking of fragments to the surfaces. In the above scenario, the accelerant tin and novel pages did not have impurities on them, hence making the powdering method most appropriate for developing fingerprints.

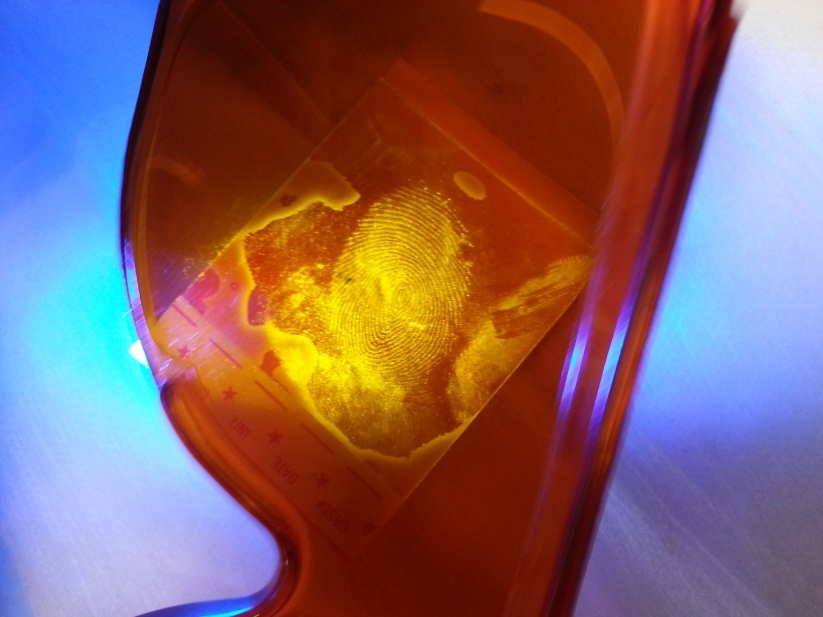

Fluorescent powder is suitable for surfaces where color or surface texture may hinder proper visualization of prints (p.202). In this case, the novel pages and accelerator tin colors would have made it hard to see the prints. Using flour magnetic powder solved this as it became possible to visualize the prints on observing under a fluorescent light.

The fingerprints were developed on the sources of evidence using the above-described methods and lifted using the tape lifting method. The lifted prints were cast in order to provide contrast and specificity for microscopic inspection. The casting process entailed the use of Mikrosil. Mikrosil takes a short time to set and can easily be removed from the mold (fingerprints) without distorting the fingerprint pattern. These properties make it the ideal material for casting fingerprints.

Photographs of the cast fingerprints were then taken and compared to the fingerprints in the suspects’ profiles. During the comparison process, the main aim was to determine whether enough similarities existed between the samples (Houck and Siegel, 2010, p.6). Houck and Siegel further inform us that individualization can only come about when more than one unique trait exists between the recognized and the sample in question (p.64). In this case, the fingerprints on the novel matched those of one of the suspects, Lindelle Hodge. The samples in question were the fingerprints from the evidence whereas the recognized samples were the fingerprints from the NSW police department database.

Conclusion

Taking into account the magnitude of evidence obtained from the experiment, the Deakins Forensic unit concluded that Lindell Hodge was the prime suspect in case 57492. Similarities between fingerprints at the crime scene and her fingerprints in the NSW police department database support this claim without any doubt. The NSW police, therefore, have all rights to arrest Lindell Hodge and subject her to questioning.

References

Houck, M. M. & Siegel, J. A., 2010, Fundamentals of forensic science (2nd ed.), Academic Press, Burlington, MA.

“Powders for fingerprint development,” 2010, in Ramotowski (ed.), Lee and Gaensslen’s Advances in fingerprint technology (3rd ed.), CRC Press, Boca Raton.

“Presumptive vs confirmatory tests in forensics”, 2012, Web.