Introduction

The concept of partnering emerged within the Japanese construction industry. Partnering refers to creation of an owner-contractor relationship which promotes achievement of mutual beneficial goals. It involves an agreement in principle to share the risks involved in completing the project, to establish and promote a beneficial partnership environment (Staveren, 2006, p. 237).

The commitment of those involved in the project is aimed at working closely instead of working as adversaries or competitors. The parties utilize such kind of design and construction methods with an aim of achieving an increased project value. They are guided by a moral charter in order to successfully implement the projects.

Partnering in Australia

The construction industry in Australia has a long lasting history of mutual partnering. The concept of partnering has significantly contributed towards the success of this industry. In the late 1980s, there was a prevalent view that an increment in the number of contractual claims and disputes in the industry had eloped in the Australian construction industry over the previous ten years.

A change in attitudes which forced parties to pursue or resist claims had been addressed often with little regard for particular merits of the claims. This inclination towards increased disputes and lawsuits as well as the changes in attitudes which promoted numerous aggressive and provoking relationships was perceived as a threat to the efficiency and well being of the industry.

Consequently, the co-operative was to be put at risk in terms of the attitudes that were necessary to achieve timely and efficient completion of buildings and construction projects. Concerns regarding this issue resulted into the formation of a Research Project Group comprising of senior management people from various stake holders such as; the Australian Federation of Construction Contractors, the Australian Institute of Quantity Surveyors and the Federal and State Government.

Construction partnering was officially introduced into Australia’s construction industry in 1992 through a series of seminars propounded by Charles Cowan. Since then, partnering in construction has been implemented in both the public and private sectors for both civil as well as building projects. Guidelines, principles and policies on partnering have also been devised and included in the New South Wales Government’s Capital Project Procurement Manual.

In 1994 the Construction Industry Institute instituted a task force whose major task was to come up with ways in which partnering preparations could augment the construction projects and industry as a whole. The endeavor of the investigation was to discover the criteria for thriving partnering, to determine what benefits mount up to the parties and eventually identify models which may be appropriated by the Australian construction industry.

The outcome indicated that there were numerous achievable approaches to partnering in the Australian construction industry in addition to varying degrees of commitment particularly on the part of industry participants and stakeholders (Stehbens, Wilson & Skitmore, 1999, p.234).

Prior to implementing partnering in a construction company, it has to be practiced and learnt over a sequence of projects (Harris, McCaffer & Edum-Fotwe, 2006, p. 87). This means that it requires an early loyalty in terms of management of the resources and direct costs. Organizations that share the same vision in terms of investing in partnering are the major contributors to the initial stages of the process.

Partnering entails an intensive investment in terms of organizing workshops that provide information to staff members and time on the part of the management in terms of instituting the necessary strategic plans. Other expenses include the costs incurred in terms of reviewing the content of the workshops and that injected into monitoring the process, valuation and instructing new organization members during the process of implementing the contents of partnering.

It is also reported that contractors incur increased overheads, quite often. Time was also necessary especially on the part of the senior staff members in terms of attending to meetings on partnering and communication of the findings and recommendation of such meetings to other members.

Definitely, effective partnering requires a competent and “time now” contract management which for some contractors, employers and organizations might regard as increased or extra expenses. Partnering in projects implementation may range from single to long term commitments. The organizations with specific business objectives capitalize on the efficacy of each other’s resources. For a successful operation, participants must have trust and be dedicated to achieving the common goals and values of the other partner.

Since its incorporation into the construction industry, partnering has improved the transactions in the construction industry in a number of ways. For example, predictability of both time and cost have improved since late design changes have became less as a consequence of early participation of carefully preferred chains of supply.

Similarly, an approach of early participation and forward scheduling increased the potential for cost reductions along with savings. In addition, a long-term relationship agreement provides a stability of works that allows contractors to comprehend the client’s desires. A pain or gain share formula also encourages supply chains to be innovative and improve performance. Further, problems are identified at an early phase and resolved in a collaborative manner.

Close communication plus partnering working within the projects reduces the defects and accident rates. Consequently, lessons learned are shared across the industry thus creating a culture of continuous progress. Finally, the findings of the processes of project assessment and standardizing presented to customers serve as markers of the progress of construction projects (Staveren, 2006, p. 238).

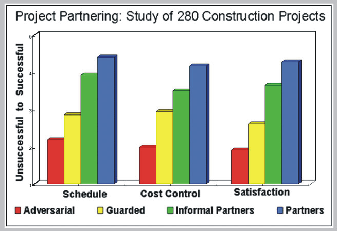

The graph above shows the findings of project assessment which indicate the extent to which construction management is successful. The data was generated from three major levels of management (that is) project results, cost control and the ability to meet project deadlines. Additionally, the process of project assessment involves measuring the ability of the construction teams and contractors to meet the required performance standards, customer requirements, and evading legal tussles among other issues.

By every measure those projects which had invested in formal partnering team building excelled over all the optional management relationships. The final result of the assessment process indicated that partnering enables engineering teams to achieve the required project performance and customer satisfaction when compared to other informal project management mechanisms that were in place (Skeggs, n.d).

Based on the findings above, it is evident that partnering contributes to numerous positive end results particularly in terms of the project upshots. However, despite the existence of misgivings in partnering, the process can benefit from additional research which will enable the stakeholders to evaluate and validate the benefits of the whole process in addition to singling out the prevailing problems.

Setbacks of partnering

Although partnering has demonstrated good construction project outcomes in the evolution of the construction industry as seen above, there are however shortcomings which are directly or indirectly linked to cost management. These disadvantages include:

Stale ideas- There are chances of gaining stability in partnership hence those in a partnership relationship become more used to each other. As a result, stimulation in the relationship deteriorates.

The contented parties may end up giving deliberate undervalued ideas to the other participants instead of giving respective interests that woud exploit the benefits of the collaboration. This is because one party may feel that it has achieved its goals using the shared resources. Naturally, some people work hard when there is some motivation of whatsoever kind.

The cost of consultations may be higher in situations where the partnering process produces more solutions which are to a greater extent alternatives of the same problem. Additionally, the cost of reviewing the content and evaluation process may overstretch the budget.This may imbalance with the level of the existing resources, hence the parties may be forced to stretch their limited resources so as to accommodate the urgency of partnering.

Reduced career prospects in the sense that the staff members involved in partnering might perceive it as an extra burden in terms of workload and something which might not in any way contribute to their career advancement.

Loss of confidentiality may also occur since partnering involves many stakeholders some of whom may be out to achieve their own interests. As such, chances of confidential information being leaked out become a common case. On this view it may be easier for the parties involved to use the leaked information as a competitive advantage instead of operating as equal partner. This may affect future relations among the parties.

Investment risk may occur in terms of investing in joint development for a project. For example, in the process of developing an electronic data intercharge system, it may be risky if the single project partnership does not extend into future contracts. As a result, the implementation of the project may be at a great risk and could at the end collapse. This would only mean a wastage of resources, time and energy since little can be done to salvage such a case.

Partnering in construction may also lead to high dependency risk especially when the partners become too dependent on each other for certain performance activities.

Corruption may arise in cases where a company strongly desires to establish partnership with another which is reputable and progressive. This leads to corrupt deals where one is willing to do anything just to secure partnership with a given company (McGeorge, Palmer & London, 2002, p.241).

Conclusion

Project partnering in Australia has registered tremendous positive development within the construction industry just after its introduction. However, it became disreputable due to the lack of alignment between the ethics and standards expected and the contractual framework that was in use. Despite this limitation, project planning has a high prospective of developing performance of the international construction industry.

There is an adequate theoretical and practical substantiation to point out that when effectively implemented, project partnering facilitates the improvement of the performance of the participating organizations. However, the benefits realized in most partnering projects are usually related to large-scale ventures rather than the small-scale projects.

There is a broad universal consciousness of partnering and a more accurate understanding of partnering along with its potential which is not widespread. Most high-ranking international industry institutions have no precise policy on partnering. It is thus imperative for partnering to be encouraged in most industries besides the construction industry.

Additionally, collaborative institutions or bodies should be established and given the responsibility of carrying out project assessment in order to provide the stakeholders with the required information pertaining project performance and validation.

Reference List

Harris, F., McCaffer, R. & Edum-Fotwe, F.2006. Modern construction management. New York: Wiley-Blackwell.

McGeorge, W. D. Palmer, A. & London, K. 2002. Construction management: new directions. 2nd Ed. [E-book].UK: Blackwell Publishing CO. Web.

Skeggs, Chris. n.d. Project partnering in the international construction industry. International Federation of Consulting Engineers. Web. Web.

Staveren, V. M. 2006. Uncertainty and ground conditions: a risk management approach. [E-book]. Great Britain: Elsevier Ltd. Web.

Stehbens, K.L. Wilson, O.D. & Skitmore, Martin, R. 1999. Partnering in the Australian construction industry: Breaking the vicious circle: Australia: Queensland. University of Technology. Web.