Study Overview

The professional work of a nurse is characterized by high physical, mental, and emotional load. There are a number of reasons for the development of occupational stress in the professional nursing job (Sharma et al., 2014) including complexities of interaction with patients, colleagues, fellow members and doctors, professional work overload, non-satisfaction with material situations, conflictual relationships of collective work, conditions of personal life, and problems of professional growth and career. The nursing profession is one of the high-risk occupations due to the emergence of occupational stress.

Many studies including Gadirzadeh, Adib-Hajbaghery, and Abadi (2017), Mudallal, Othman, and Al Hassan (2017), and Williams (2014) have identified the influence of occupational stress on physicians’ performance and personality.

Numerous factors were found to affect the mental and physical wellbeing of nursing professionals. In this study, various strategies have been identified, which can help nursing professionals to reduce the occupational stress. The research is based on the primary research question – how nurses cope with job stress? The study collects data from six nursing professionals through a survey questionnaire and analyzing their responses.

Literature Review

Stress is one of the essential components of adaptation processes and the way of living of human beings. The body reacts to stress with the help of the “fight-or-flight” reaction. The stress response plays a vital role in the body’s defense and survival of living organisms (Filha, Costa, & Guilam, 2013), which is provided by periodic releases of catecholamines. However, the duration and frequency of such releases are significantly higher than physiological capabilities with the continuous stress faced by nurses in the healthcare services.

Eventually, regular releases of endorphins and catecholamines cause stress reactions and increase the possibilities of blood pressure, headache, cardiovascular diseases, depression, and many other health disorders.

Almost every individual struggle with different types of stress. However, occupational stress is a situation in which different job-related factors came in contact with a professional individual, changing his/her physiological and psychological condition in a way that he/she tends to depart from normal functioning (Filha et al., 2013).

In the context of nursing professionals, stress is one of the leading causes of impaired physical and mental health. Many factors contribute to the development of stress among nurses. The most common stressors include workload, the behavior of senior doctors and physicians, professional growth, and career (Lorenz & Guirardello, 2014).

According to the study by Sarafis et al. (2016), there is a correlation between occupational stresses, the behavior of nurses, and the quality of life concerning their health has been explored and investigated. It has been found that occupational stress negatively affects the health-related quality of life of nursing professionals, which also as an influence on patient outcomes (Sarafis et al., 2016).

The research literature describes the symptoms of stressful occupational disorders, and some of them disrupt the productivity of nurses. It includes memory impairment, increased distractibility, and lack of concentration at work. Furthermore, stress promotes violent behavior, dependence on various drugs, development of somatic diseases (especially cardiovascular), and causes an increase in the incidences of suicide among nurses. It is revealed in the study by Hosseinabadi et al. (2018) that stress at work in the nursing profession is the leading cause of exhaustion.

It is not possible to reduce or eliminate stress in the context of Exposure Prone Procedures (EPP), but nurses could learn how to react to it (Mudallal et al., 2017). The impact of stress on the body and the psyche of a person depends entirely on his/her response to stress. Therefore, nurses need to learn how to manage their reactions to stress.

A randomized controlled trial conducted by Jordan, Khubchandani, and Wiblishauser (2016) examines the effect of music on self-perceived stress among first-line nursing professionals. The findings of the study provide evidence for nurses to use relaxing and soothing music as a research-based intervention for reducing stress.

A study by Ghaffari, Dehghan-Nayeri, and Shali (2015) investigates humor therapy, mindfulness training, mentors, and peer instructors as strategies to reduce anxiety among nursing students in the clinical setting. Furthermore, the clinical environment serves as a significant learning environment for young nursing professionals, and it also presents many challenges that might result in nurses experiencing anxiety and stress (Williams, 2014).

Survey Methodology

The selected methodology for the study performs a mixed research by combing qualitative and quantitative methods of analysis. The qualitative part of the study includes a literature review of peer-reviewed research studies in the context of occupational stress and coping strategies followed by nursing professionals in a clinical setting.

The quantitative part of the study involves the collection of responses from six nurses (3 males and 3 females), who were purposively selected for this study (Creswell, 2014). The respondents were explained the purpose of the research and questions included in the questionnaire. They completed the survey in the presence of the researcher. The data was collected by using a closed ended questionnaire consisting of 12 questions.

Strategies used by nurses to cope with job stress were determined by using a closed-ended survey questionnaire. The responses of both male and female nurses helped in comparing their views to get a better understanding of occupational stress and coping strategies. The questionnaire includes questions related to demographics and work experience such as gender, age, working experience, working shift, and employment ward. Moreover, some of the questions inquire about physical and mental health symptoms experienced by nurses and anti-stress therapies that they prefer.

The language used for drafting questions is simple and all respondents easily understood them. While administering the survey, I felt that respondents were hesitant to participate. However, there was no need felt to change these questions after the researcher started administering the survey. If a similar study is carried out in the future, then I would add questions about other coping strategies. Furthermore, I would compare different nursing groups based on their demographics such as gender.

Results

The results of the study are derived from the analysis of the data collected through the survey. The results are demonstrated in the form of percentages for a better indication of the collected responses. The stress estimation is carried out by using different factors such as gender, age, employment ward, working shift, physical and mental health symptoms, and different anti-stress therapies.

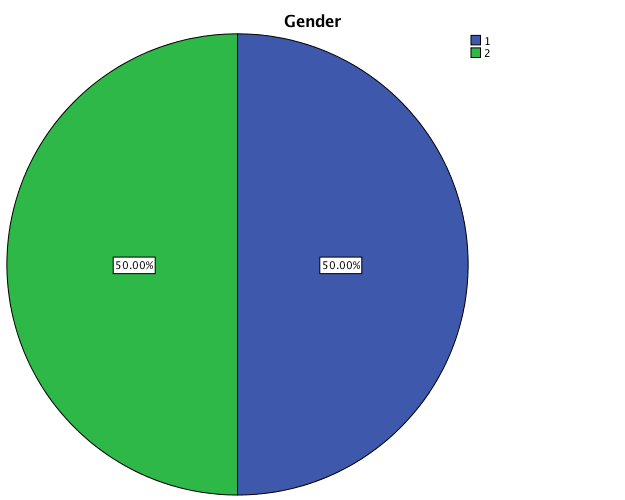

Table 1 shows that the survey included three male participants and three female participants. It is also graphically represented in Figure 1.

Table 1. Gender.

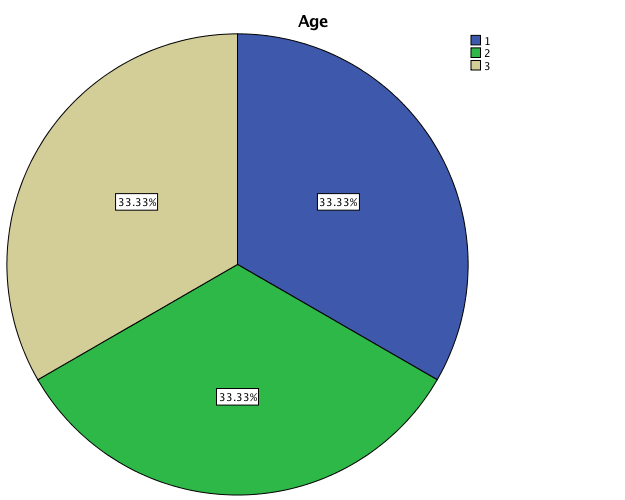

Table 2 shows that four participants (66.6%) out of six are aged between 20 and 30 years. The other 33% of respondents are in the age group of 31 & above. It is also graphically represented in Figure 2.

Table 2. Age.

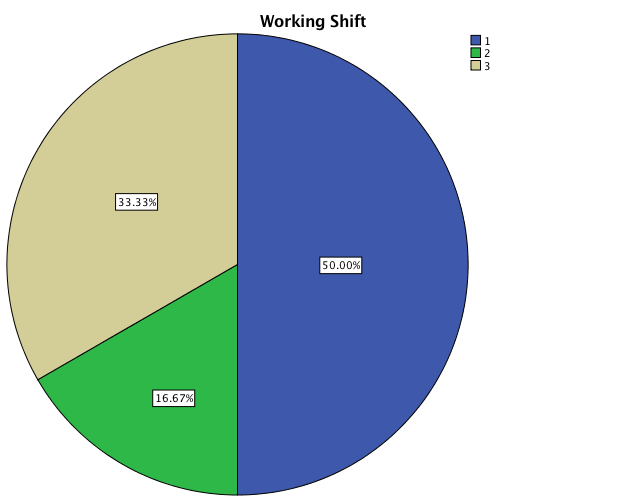

Table 3 shows that 50% of the respondents work in the day shift, whereas 33% of them work in the night shift. The remaining 16% work in the afternoon shift. These results are graphically represented in Figure 3.

Table 3. Working Shift.

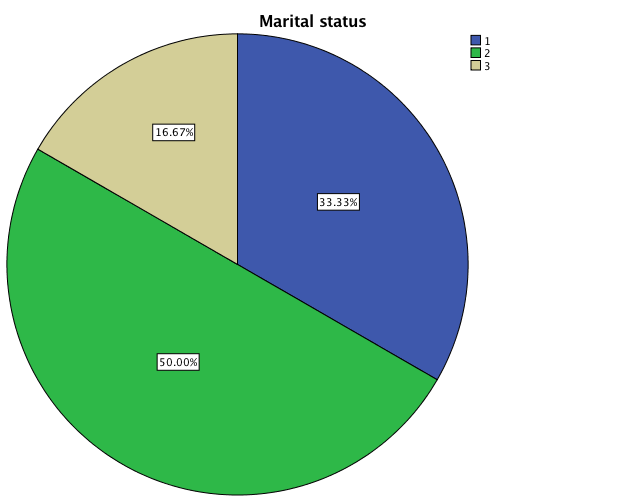

Table 4 shows that 50% of study participants are unmarried. Moreover, 33% of them are married, and 16% are either divorced or separated. This finding is also graphically represented in Figure 4.

Table 4: Marital Status.

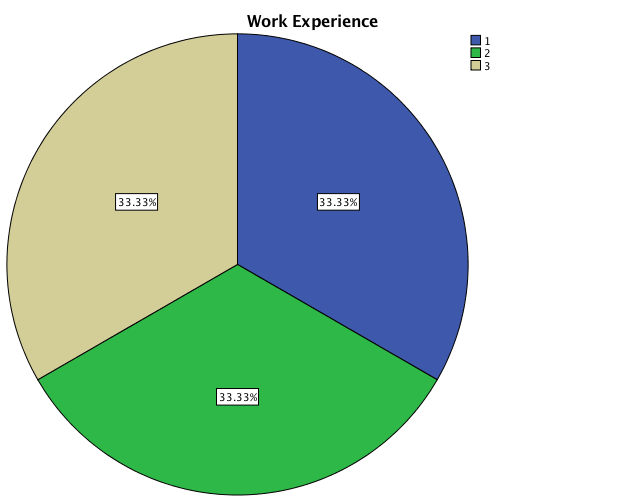

Table 5 shows that 33% of the participants are young nursing professionals with 1-6 years of experience. However, two participants are in the category of registered nurses having experience of 7-12 years, and the remaining 33% of the respondents are senior nursing professionals at the managerial level with more than 12 years of experience. These findings are also graphically represented in Figure 5.

Table 5. Work Experience.

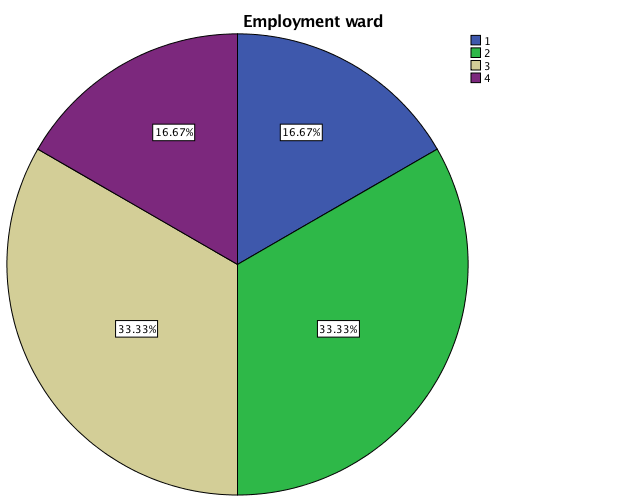

Table 6 shows that 33% of the participants work in the surgical ward, whereas 16.7% of them work in the medical ward. Moreover, 33% of the respondents work in emergency and 16.7% work in the pediatric ward. These results are also represented in Figure 6.

Table 6. Employment Ward.

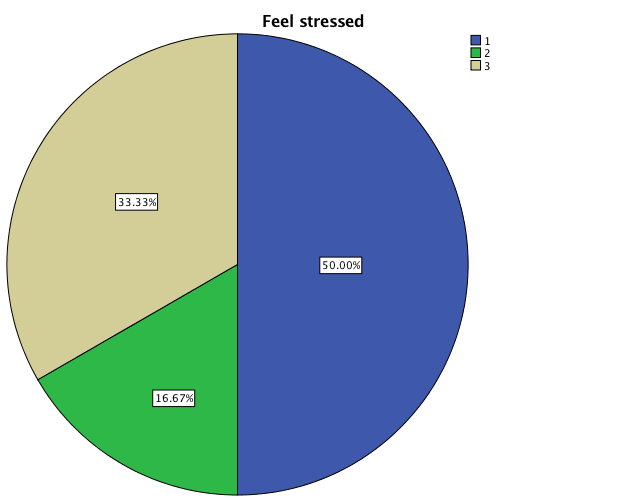

Table 7 shows that 50% of the study participants feel stressed daily or on alternate days, whereas 33% of them usually feel stressed once a week and only 16% replied that they feel stressful twice a week. It is also graphically shown in Figure 7.

Table 7: Feel stressed.

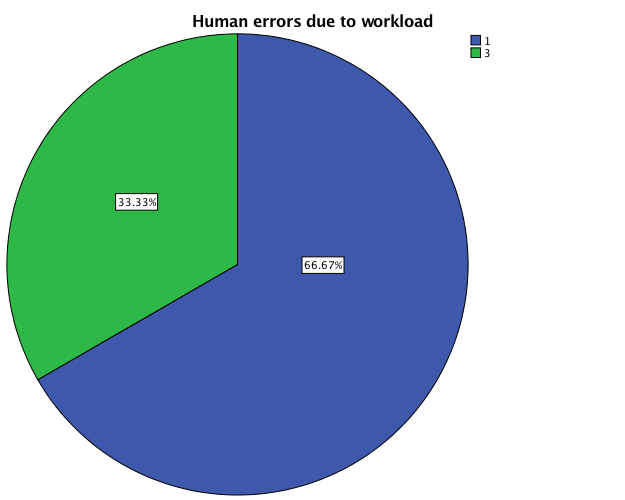

Table 8 shows that the majority of the participants, i.e., 66% indicated that they make medical errors on a daily basis due to the increased workload. Furthermore, the remaining 33% of them responded that they incur medical errors on a weekly basis. These results are also shown in Figure 8.

Table 8. Human Errors due to Workload.

Table 9 shows that depression and feeling tired and difficulty concentrating are the most common mental health symptoms indicated by all participants. However, changes in behavior were identified by 50% of the participants, whereas 33% of them show anger. It is also graphically represented in Figure 9.

Table 9. Mental Health Symptoms.

Table 10 shows that the majority of the participants (83%) feel dizziness and restlessness, which are the most common physical symptoms of stress. Moreover, difficulty in sleeping is also indicated by 50% of the participants, and 33% also reported that they experience specified cramps and muscle spasm due to anxiety and stress. Figure 10 graphically represents these results.

Table 10. Physical Health Symptoms.

Table 11 shows that 60% of the participants do physical exercise to reduce stress, whereas 33% of them choose practicing meditation for minimizing their anxiety. Furthermore, 50% of the participants prefer listening to music to lower their stress level, and the rest of them utilize massage therapy to ease tension and headache. The results are also represented in Figure 11.

Table 11. Anti-stress Therapy.

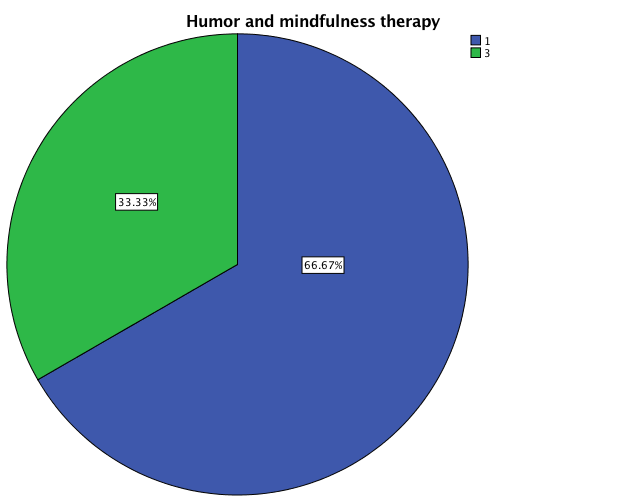

Table 12 shows that 66% of the participants think that humor and mindfulness therapy helps in reducing stress among nursing professionals. However, 33% of them do not have any idea about this therapy. The results are also graphically represented in Figure 12.

Table 12. Humor and Mindfulness Therapy.

Study Critique

The research was carried out to determine how different strategies help to cope with stress among nursing professionals. For this purpose, the research was conducted in two steps to present qualitative and quantitative information. In the qualitative part, different research studies related to stress and its impact on physical and mental conditions of nursing professionals have been retrieved. These studies help in identifying different strategies used for reducing stress among nurses.

They also assist in determining the significant stressors that influence the health-related quality of life of nursing professionals in the healthcare setting. In the quantitative part of this report, the data was collected by surveying six nursing professionals. The researcher collected information for research purpose only after getting consent from the participants. However, the participants’ personal information is not included in the report for ensuring their confidentiality.

The results of the study indicate that the majority of nursing professionals encountered stress-related mental and physical symptoms. Among them, the most common symptoms are depression, dizziness, feeling tired, restless, and difficulty in concentrating at work. Furthermore, the most common strategies used by nurses for reducing their stress are physical activities (yoga, work out, walk), music (soothing, trance, relaxing), and massage therapy. However, humor and mindfulness therapy is also considered significant in reducing anxiety and depression among nursing professionals.

Limitations of the Study

Insufficient representation of the nursing population due to the small sample size is a significant limitation of the current study design, which has a considerable impact on the research outcomes. The study also has an impact limitation as despite having complete data and statistics as intended, the study suffers from a limited impact due to the lack of regional focus.

As the survey collects data only from only one healthcare facility, its results could not be generalized to all nursing professionals. Moreover, the qualitative part of the study only includes secondary data and does not present any conceptual or comparative framework. The lack of theories and frameworks affect the reliability of the current work.

References

Creswell, J. W. (2014). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications Inc.

Filha, M. M., Costa, M. A., & Guilam, M. C. (2013). Occupational stress and self-rated health among nurses. Revista Latino-Americana de Enfermagem, 21(2), 475-83. Web.

Gadirzadeh, Z., Adib-Hajbaghery, M., & Abadi, M. J. (2017). Job stress, job satisfaction, and related factors in a sample of Iranian nurses. Nursing and Midwifery Studies, 6(3), 125-131. Web.

Ghaffari, F., Dehghan-Nayeri, N., & Shali, M. (2015). Nurses’ experiences of humour in clinical settings.Medical Journal of The Islamic Republic of Iran, 29(182), 1-11. Web.

Hosseinabadi, M. B., Etemadinezhad, S., Khanjani, N., Ahmadi, O., Gholinia, H., Galeshi, M., & Samaei, S. E. (2018). Evaluating the relationship between job stress and job satisfaction among female hospital nurses in Babol: An application of structural equation modeling. Health Promotion Perspectives, 8(2), 102-108. Web.

Jordan, T. R., Khubchandani, J., & Wiblishauser, M. (2016). The impact of perceived stress and coping adequacy on the health of nurses: A Pilot Investigation.Nursing Research and Practice, 2016, 1-11. Web.

Lorenz, V. R., & Guirardello, E. d. (2014). The environment of professional practice and burnout in nurses in primary healthcare. Revista Latino-Americana de Enfermagem, 22(6), 926-33. Web.

Mudallal, R. H., Othman, W. M., & Al Hassan, N. F. (2017). The influence of leader empowering behaviors, work conditions, and demographic traits.The Journal of Health Care Organization, Provision, and Financing, 54, 1-10. Web.

Sarafis, P., Rousaki, E., Tsounis, A., Malliarou, M., Lahana, L., Bamidis, P., & Papastavrou, E. (2016). The impact of occupational stress on nurses’ caring behaviors and their health related quality of life.BMC Nursing, 15(1), 56-65. Web.

Sharma, P., Davey, A., Davey, S., Shukla, A., Shrivastava, K., & Bansal, R. (2014). Occupational stress among staff nurses: Controlling the risk to health. Indian Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 18(2), 52–56. Web.

Williams, K. T. (2014). An exploratory study: Reducing nursing students stress levels facilitate perceived quality of patient care. Open Journal of Nursing, 4(7), 17-23. Web.