Introduction

Hedgers are the participants in the derivatives market who come into the market to minimize the risk. They are, therefore, essentially the market makers (Scholes, 1998). The hedgers introduce the numerous contracts that the other participants can trade with to make profits (Ritchken, 1996). The hedgers can be trying to minimize the risk of decline in prices for producers of commodities or rising prices for buyers of commodities. They keep the derivatives market constantly in the supply of new contracts.

Hedgers are also the ones who create the price in the market since their moves are not influenced by the need to make profits out of the derivatives markets movements. Hedgers are influenced by the underlying assets values and the expected price movements of their products. The derivatives trade would for that reason be a zero-sum game if hedgers are excluded (Briys, 1998).

Speculators are those individuals who get into the derivatives markets simply to make a profit out of their superior skills at analyzing markets than the hedgers. The speculators usually have no interest in the underlying commodities and as a rule hope to trade the positions frequently and make profits (Francis et al, 1995). Given the risk inherent in derivatives markets this is not always the case and the losses are just as frequent as the profits. However, their main contribution is the creation of enough liquidity in the markets and therefore facilitates the risk transfer that is afforded by the derivatives markets (Veale, 2001; Taylor, 2007).

The speculators usually have better information than the hedgers on the likely movement of the prices in the commodities being dealt with by the hedgers. This makes them stand to benefit from the superior information possessed (Wilmott, 1998). This in turn benefits the hedgers who can get superior hedges for their products which they would not otherwise get by themselves. The speculators are therefore the ones who facilitate price discovery. However, their speculation may hurt the market as well for the hedgers since their main drive is the profit motive and not the welfare of the hedgers (Chance, 1998). This is however restricted by the regulators who apply the various regulatory measures on the extent to which the speculators can influence the markets.

Hedging Strategies and Outcomes

The fund manager wants to minimize the risk of loss while maximizing the returns. A loss can only be incurred if the market falls. Therefore, the fund manager will only protect his fund from a downward fall by buying the European call contract. Since I am very sure of the market and certainly sure it will go up, I will buy the European put option. The following are the outcomes.

The strategies show that when the market declines the fund manager will make a profit from his hedge and therefore offset his losses on the portfolio, and when the market goes up he will make a loss on his hedge and make a profit on the portfolio which will offset each other. The hedge will therefore have served its purpose.

Therefore, the only chance I have of making a profit on the derivatives market is if the market goes up. Having some £ 10 Million to invest in a market that I believe will go up I will make huge profits if the market goes up on the portfolio and the speculation. However, if the market goes down, I will lose on my investments and my speculation position in the derivatives market.

Speculative Strategy

If the FTSE 100 will rise far above the FTSE 2700 mark, and it is also possible for it to fall below FTSE 2500 then the following strategy can be used to speculate on the market:

Purchase the FTSE 2700 call option at 50p and purchase the FTSE 2500 at 40p at the same time.

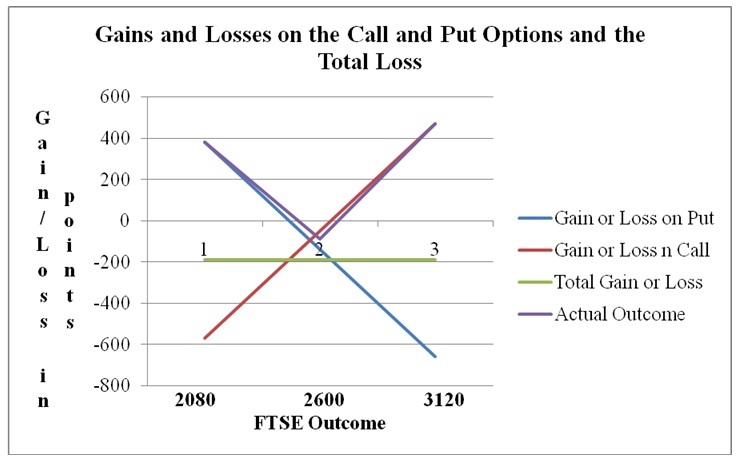

Since the options just confer the right to buy not the obligation to sell or buy the underlying security the losses can be avoided for any of the options when the movement is unfavorable as the value shows (Neftci, 2000; Hull, 2008). Due to this unique facility of the options, the losses are minimized to 90p only when the FTSE moves 2600 since both options will not be exercised and will be allowed to lapse with the purchase cost being the only loss. The options, therefore, offer better profit prospects than a complete hedge which would result in a loss for all the outcomes. The following is a graph of the performances:

The graph shows that the speculation strategy of using a call and a put option at the same time minimizes the loss at a level above the sum of the gains of the strategies at any given time and maximizes the gains at both extremes.

The graph as well shows the differing progress of the gains as well as losses for the call with put alternative. When the gains are high for the put option the losses are high for the call option which is the basic nature of their hedging capacities. This indicates that it is possible to benefit in a derivates market when the general markets either decline or rise (Valdez and Wood, 2003).

Strategies

The risk of rising interest rates is real for the treasure and therefore since the rates cannot be predicted well in advance it is easier to incur a small cost now to prevent the possibility of a huge cost in the future (Saunders and Cornett, 2008; Chance and Brooks, 2008). All the contracts available to the treasurer will come at a premium which is the charge of uncertainty. However, since in this case the transaction cost is assumed away as well as market imperfections, the options are available at per value.

The treasurer has the option to use the forward rate agreement that will guarantee the interest rate is locked in. This agreement is however available at 6% which indicates that the rate that will be locked in will be higher than the current level of 6%, however, given the risk this contract may be favorable. A forward contract will obligate the company to receive the loan at the end of six months at the current rate plus the 6% charge. This contract is fixed. And therefore, if the rates fall between these periods the company will have made a loss. The treasurer will therefore have to be very sure of the expected movement of the interest rate. If he feels that the rate will move by more than the 6% charge on the forward rate agreement, then this agreement can form a good hedge for the company.

The other strategy that the treasure can employ is the sterling interest futures that are available at 94 to hedge the risk of rising interest rates. The futures will also lock in the interest rate at 6 percent since they are being sold at 94. This implies that the treasure will also have to review the position of the interest rates and ensure that the interest rates are likely to rise by more than six percent in the future. If this is the case the future offers a good strategy to hedge the risk of rising interest rates.

Profits and Losses on the positions with changes in interest rates

The positions show that when the interest rates fall to 4% both strategies will lead to a loss of £ 600,000 since the locked-in interest rates will be higher than the prevailing markets rates. This loss however will be again to the writer of the contracts on the other hand. When the rates go up to more than 6% as the treasurer anticipates both strategies leads to a gain of similar amounts.

Advantages of Forwards over Futures in Hedging

The forward contracts are not usually limited in amounts and can be written for almost any amount. This is a great advantage since firms experience hedging needs of different amounts and sizes at different times. The futures on the other hand are limited in terms of sizes, and duration limiting the flexibility of the hedge (Winstone, 1995; Taylor, 2011).

The forward contracts also offer complete hedges as opposed to futures that have divisibility problems. This makes the forward contracts very favorable for huge volumes of hedges (Fabozzi, 1998).

The forward contracts are also purely based on the agreement between the parties involved which mainly rely on their future needs for the resources involved and the profit motives. This makes the default risk very low since both parties face similar circumstances that are easy to predict in the long run (McDonald, 2006). Futures on the other hand are based on some other underlying securities whose risk is not purely related to the terms of the agreement. Default on the underlying securities may lead to a default on the futures contract without the intention. Futures are therefore riskier than forwards (Peck, 1985a).

Disadvantages of Forwards over Futures

Since the forward contracts are based on the specific terms of the party looking to hedge it suffers from the batter trade problem of not being able to find a suitor in good time. It is not likely that every forward contract offer will be met will a similar offer to close it. This lack of liquidity makes forward contracts less favorable to futures in hedging risks (Liaw and Ronald, 2000).

The contracts also require huge amounts of capital being tied up as opposed to highly leveraged futures, and not much capital is necessary. Resources held up incur the opportunity cost since if invested in other short-term assets it would be able to earn higher returns. This makes forward less favorable and tends towards being more costly than futures for the same amount of hedge.

Also, the default risk of the forward contract at the contracting party level is higher than that of the futures contracts due to the high amounts involved and the difficulty in closing the contracts before the term of the contract is over. Futures on the other hand are easily traded and therefore can be closed before the term is over reducing the risk of default.

Swap

Company ABC is being offered the same rates for its dollar and pound loans While XYZ is being offered different rates for its dollar and pound loans. This difference creates an opportunity for an interest rate swap between the banks. It is, therefore, possible for a swap bank to benefit from the arrangement by taking the loans itself and offering the banks the loans at well-calculated rates that will out-compete the market rates offered to the banks as follows:

Since the interest rate charged on the pound loan for ABC is equal to the rate charged for its dollar while that of XYZ is higher for the pound, the swap bank will take the pound loan using the terms of ABC and the dollar loan using the terms of XYZ. The bank will therefore have the following amounts:

The Bank will then offer the respective loans in the preferred currency since the currencies are assumed to be freely exchangeable in the markets by the bank. ABC will be offered a loan that will include the profits that the bank intends to earn plus the discount that has to be charged to make the funds available to XYZ at a rate that is more competitive than the market rate it is being offered as follows:

Loan offered in Dollars to ABC = $ 30 Million at 8.9 % for 10 Years

XYZ on the other hand will be offered a loan in pounds that will be offered in the followings terms

The average interest rate charged on the loans forms the cost of the money for the swap bank and therefore the profit margin of 0.2 % is charged over and above the average interest rate. The bank however has to ensure that each company gets a rate that is better than the market rates.

Loan offered to XZY in Pounds = £ 20 Million at 8.3 % for 10 Years

Assuming the convertibility of the dollar and the pound remains the same the company and the swap bank will be able to earn 0.2 percent on the interest paid by ABC and a further 0.2 % to reduce the rate of interest paid by XYZ. Both companies now have much better rates compared to what is available in the markets and the bank can secure some profits by acting as an intermediary. The whole arrangement, therefore, benefits everyone.

Risk Faced by Swap Banks

The Swap banks engage in a variety of activities that put them at a lot of risks. They can engage in interest rate swaps, exchange rate swaps, or even period swaps. All these types of swaps involve the bank exposing itself to some risk on behalf of other parties at the prospect of some profits (Gardner, 1996; Howells and Bain, 2004). The Swap banks are faced with many risks by acting as intermediaries for swaps as follows:

Exchange Rate Risk: By swapping different currencies loans the swap banks relies on their ability to predict the movements of exchanger rates. This risk would not be there if the exchange rates were fixed. However, the current situation is that exchange rates are freely floating for a majority of the world countries exposing the swap banks to very huge risk (Gardner, 1996). When the exchange rates change in a way that the swap banks had not anticipated the loss is huge since the contracts will have to be fulfilled at the rates agreed (Whaley, 2006).

Interest-rate Risk: Swap banks also usually anticipate the movement of interest rates in creating their swaps. The interest rates are extremely volatile and as a result, the swap banks are exposed to adverse movements. Swap banks usually benefit from timing differences of payments as well as differences in interest rates in different markets (Jorion, 2009). When interest rates change the returns made on the funds change and therefore the obligations of the bank change. This increases their risk and therefore their cost of capital as well.

Default Risks: The successful operation of a swap is based on both parties involved fulfilling their obligations. If one of the parties fails to fulfill their obligations the swap bank has to get in and fulfill its part to the party that is still honoring its promises. This is because sometimes the involved parties do not contract directly and they do not know each other. This exposes the banks to huge losses (Gardner, 1996).

Functions of Financial Innovations

financial improvements have been disputed to be the utmost donor to the banking sector breakdowns and nearly all of the financial catastrophes that have arisen recently. One of the most popular forms of financial innovations in derivatives (Jarrow and Turnbull, 1996). Although derivatives have been argued as very beneficial to the financial market since they facilitate price discovery, enhance liquidity, and also facilitate risk transfer they also increase the risk that investors are willing to take. One of the major reasons for this is their complicated nature (Peck, 1977b; Hull, 2006). Very few investors can participate in the derivatives markets successfully, and therefore banks having the largest amounts of information on financial trends tend to be the greatest participants (Kolb, 1994; McDonald, 2008).

This exposes them to the huge amounts of risk that are involved. Many banks do not usually capitalize themselves well to cater to the risk involved in the derivatives market. The regulatory authorities are always behind the practice since the innovations are very complicated for capital models to be developed in time. As a result, the banks take on a risk that they are not prepared to cover with their capital increasing the chances of failure (McLauglin, 1999). One contributor to the huge temptation in the derivatives markets is the extensive use of leverage. This promises immense returns compared to other conventional investment avenues. However, the huge leverage also implies that the losses incurred might just as well exceed the amounts the investors have leading to the collapse of the whole system (Klein and Lederman, 1994).

Another form of financial innovation that is contributing to the banking sector’s problems is securitization. The most recent financial crises are argued to have been brought about by unchecked speculation in the securitized sub-prime mortgage securities. By being able to offload the risk of the subprime mortgages from their balance sheets through securitization banks engaged in runaway speculative behavior leading to a decline in the due diligence applied in the issuance of the mortgages (Pilbeam, 2005). As a result, the risk inherent in the securities became so high and the market collapses. This kind of financial innovation has also escaped regulators due to the pace with which it has been implemented.

List of References

Briys, E., Mondher, B., Minh M. H. & Francois, V. (1998). OPTIONS, Derivatives Exotic and Futures. New York: John Wiley and Sons.

Chance, D.M. and Brooks, R. (2008). An Introduction to Derivatives and Risk Management, 8th Edition, London: Thomson South-Western.

Chance, D. M., (1998). An Introduction to Derivatives, NY: The Dryden Press.

Fabozzi, F J., (1998). Treasury Securities and Derivatives, London: Frank J. Fabozzi Associates

Francis, J; William, T and Whittaker, G. (1995). The Handbook of Equity Derivatives. NY: Irwin Publishers.

Gardner, D.C. (Ed.). (1996). Introduction to Swaps. London: Pitman Publishing.

Howells, P and Bain, K (2004). Financial Markets and Institutions, 4th Edition, NY: Prentice.

Hull, J (2006). Options, Futures and Other Derivatives (6th Edition) NY: Prentice.

Hull, J. (2008). Fundamentals of Futures and Options Markets, NY: Prentice Hall.

Jarrow, R A. and Stuart M. T. (1996). Derivative Securities. South-Western. Ohio: Cincinnati.

Jorion, P (2009). Financial Risk Manager Handbook (5 ed.). NY: John Wiley and Sons.

Klein, R A. and Jess Lederman (eds.). (1994). Derivatives and Synthetics. Chicago, Illinois: Probus.

Kolb, R, (1994). Futures, Options, and Swaps. Florida: Kolb.

Liaw, T and Ronald, M. (2000). The Irwin Guide to Stocks, Bonds, Futures, and Options: A Comprehensive Guide to Wall Street’s Markets. NY: McGraw-Hill.

Marthinsen, J. (2009) Risk Takers: Uses and Abuses of Financial Derivatives, London: Pearson.

McDonald, R. (2008) Fundamentals of Derivatives Markets, London: Pearson.

McDonald, R.L. (2006) Derivatives markets. Boston: Addison-Wesley

McLauglin, R M. (1999). Over-the-Counter Derivative Products. NY: McGraw-Hill.

Neftci, S. (2000). An Introduction to the Mathematics of Financial Derivatives. London: Academic Press.

Peck, A E. (Ed.). (1977b). Selected Writings on Futures Markets, Volume I and II. NY: Chicago Board of Trade.

Peck, A E. (ed.). (1985a). Futures Markets: Their Economic Role. Washington, D.C: American Enterprise Institute.

Pilbeam, K (2005). Finance and Financial Markets, 2nd Edition.NY: Macmillan.

Ritchken, P. (1996). Derivative Markets: Theory, Strategy, and Applications. . New York: HarperCollins.

Saunders, A. And Cornett, M.M. (2008) Financial Institutions Management: A Risk Management Approach, NY: McGraw Hill.

Scholes, M (1998). Derivatives in a Dynamic Economic. American Economic Review 88(3) (June): 350-70.

Taylor, F (2011) “Mastering Derivatives Markets” a step by step guide to the products, applications and risks” (4th Edition) FT: Prentice Hall.

Taylor, F. (2007). Mastering Derivatives Markets.NY: Prentice Hall.

Valdez, S and Wood, J (2003) An Introduction to Global Financial Markets, 4th Edition NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

Veale, S. (2001). Stocks, Bonds, Options, Futures, 2nd Edition. NY: New York Institute of Finance.

Whaley, R. (2006). Derivatives: markets, valuation, and risk management. New York: John Wiley and Sons.

Wilmott, P. (1998). Derivatives: The Theory and Practice of Financial Engineering, New York: John Wiley and Sons.

Winstone, D. (1995). Financial Derivatives International.London: Thompson Business Press.