Introduction

Private equity (PE) refers to a specific type of investment that individuals and organisations correlate with long-term and sometimes medium-term financing where an investor or group of investors buy large stakes in firms not publicly traded. If they are publicly traded, the firms whose stakes are purchased in large numbers may become delisted.

Usually, private equity firms and private equity funds take part in these transactions. Also, the stakes purchased in private equity deals are normally large enough to give the purchaser controlling powers over the purchased company. Another unique aspect of private equity transactions is that they are highly leveraged.

Apart from that, participants often take into consideration interest rates and tax issues before signing the deal. The occasional repercussion of tax issue and interest rate consideration is that some private equity firms may assume the asset raider role. Despite their unconventional characteristics as investment options, PE transactions foster innovation within organisations. They also increase employment opportunities and, most importantly, ensure that firms have the funds they need to remain in business.

Forms of Private Equity Transactions

As noted, PE deals are forms of investment, just like venture capital. However, they differ from venture capital in two fundamental ways. First, venture capitalists focus on new or rising organisations whereas PE looks at mature companies. Venture capitalists will invest their money in rising companies with great potential, and this is not usually the case with PE firms. Second, venture capitalists tend to be minority investors whereas private equity firms are majority investors.

As noted earlier, private equity firms often buy a controlling stake in the Target organisation, most of whom are not traded publicly. In case the purchased company is publicly listed, the PE deal may convert it into a private entity. In this regard, various forms of private equity transactions exist. Common types include leveraged buyouts, management buyouts, and institutional buyouts. Notably, the different kinds of private equity transactions are also referred to as different equity transaction strategies. In other words, investors (whether individuals or firms) may use the three strategies mentioned above to buy a controlling stake in an organisation. Each of these types will be discussed in detail focusing on their structure, mechanics, and economic role.

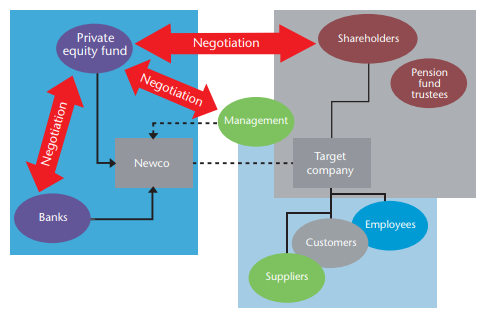

Notably, parties to private equity transactions are private equity fund managers, the company, and the bank proposing to lend some of the needed money. The fund manager’s role is to ensure the proper utilisation of the funds pooled together while managers supervise the resources on behalf of the investors. The company, including its management and shareholders, participate in the private equity transaction negotiation. They put their collective offer on the table and react to counteroffers.

The company’s management informs the shareholders of the proposed buyout so that they can either approve or reject it. If the proposed private equity transaction is a buyout, as it often is, a bank may be involved. The bank will lend the private equity fund or firm the money it needs to purchase the identified organisation, whether it is private or publicly listed. If it is publicly traded, the firm will be delisted upon the completion of the private equity deal. The three parties taking part in the private equity transaction have different risk exposures and expectations/rewards.

In private equity transactions, Banks manage risks in various ways. First, the bank has a series of monitoring tools to see if a business performs according to the initial plan. The tools enable the bank to make appropriate adjustments and decisions to prevent potential losses from happening. The monitoring tools, which are also called financial covenants, alert the bank whenever the organisation does not perform according to plan. Second, banks reach agreements with lenders before providing any funding. In these initial agreements, the creation of financial covenants is one of the most important undertakings.

By reaching an agreement with the lender, the bank prevents any potential misfortune and legal action being taken against it. Also, the agreements give the banks some legal authority. For example, in case the lender breaches any of the terms agreed upon, the bank will have a series of alternatives available to them to mitigate the risks arising from such breaches. One of the available options could be renegotiating the terms of the loan; another option is putting the lender under receivership to recover the loaned amount. Thus, the management of the private equity firm must be careful when negotiating a loan.

Leveraged Buyouts (LBOs)

Leveraged buyouts (LBOs) are by far the most important private equity transactions. It refers to the process through which a management team acquires an organisation from its current owners with the involvement of a substantial amount of borrowed funds. The acquired organisation is called the target company. The existing management or a new one could supervise the acquisition. Usually, leveraged buyouts are completed with assistance from debt financiers (like financial institutions) and private equity providers. Often, this is achieved through the establishment of a group of new organisations that manage the process.

The simplest of these groups of companies usually comprises Newco and Newco2, with Newco being the topmost company in the group. The management and private equity providers own the company. Investors will use Newco as their investment vehicle while Newco2 is a wholly-owned subsidiary of Newco. Newco2 serves as the purchasing and bank debt vehicle. With this type of structuring, the debt provider’s recourse is limited. Therefore, the private equity fund offers no guarantee that the bank loan will be repaid. A simple relationship of the different participants of a leveraged buyout is illustrated in Figure 1 below.

In leveraged buyouts, financial assistance will always arise when some form of security is provided. In most cases, banks demand to use the target company as security. For instance, the bank may demand that it uses the target company’s assets as security, which means that the target company can and often does play a role in raising the needed funds for its acquisition. Most firms will not provide any financial assistance if the target company is not used as collateral. Another thing to note is that after a leveraged buyout, three important changes occur. The first one is an increase in financial leverage. It benefits the company making the acquisition. The second significant change is a shift in the management of the organisation. The shift is inevitable as the new owners assume the leadership of the firm. Lastly, a status transition occurs; a public company becomes delisted because the new majority owner is a private entity. The three changes are inevitable.

Mechanics

Many business people prefer the utilisation of LBOs for various reasons. First, LBOs offer superior tax advantages. These are often derived from debt financing. When companies choose to finance their investments with debt, they get access to a wide variety of tax advantages. Second, leveraged buyouts give the participants freedom from the scrutiny of public operations. This is especially advantageous to the firm that is formed after the deal is completed. The firm will assume private operations that ensure the maintenance of trade secrets and other important components of successful corporations.

Another advantage of a leveraged buyout is that founders can enjoy liquidity events without sacrificing their involvement in the running of the company. Also, the founders do not have to cede their operational influence to enjoy liquidity events. Apart from that, the managers of a company have a better chance of owning a significant number of shares in the new company. Holding a substantial amount of a company’s equity gives managers the incentives they need to be creative, innovative, and results-oriented, which leads to increased organisational performance.

The mechanics of LBOs are the same, but each transaction is unique. For instance, each LBO transaction has a unique capital structure. However, for all LBOs, the one thing that stands out is the completion of the deal using some financial leverage. Most private equity funds borrow money to acquire the target company because this is seen as a desirable, low-risk approach. Using a combination of equity and debt, the purchaser finances the acquisition of the target company. The process is almost the same as when an individual is buying a house using a mortgage. In a mortgage, the loan amount is secured by the value of the house.

In the same case, the assets of the company to be bought will serve as security for the loan. It is this attractive security that makes financial institutions willing and able to take part in financing the acquisition of the target company, more so because the private equity firm cannot guarantee the loan. As a risk minimiser, the private equity firm through the management will negotiate favourable terms that put none of its finances or assets at risk. The negotiations will either make or break the deal.

Once the deal is completed, the bought-out business generates revenues that are used to finance the loan. The way the loan is repaid will depend on the specifics of the agreement. Thus, acquiring a firm through leveraged buyouts presents the purchaser with low risks; they do not pay for the deal with their equity and they do not repay the loan with existing capital. In a sense, it is the acquired company that lends itself to the loan process and the subsequent repayment of the loaned amount hence the term “bootstrap acquisition.”

The work of the acquiring company seems to be negotiating the deal and ensuring that its terms and conditions are followed to the letter. When the leveraged buyout is successful, equity holders receive high returns partly because debtors are locked, predominantly, in a situation where they receive specified returns while equity holders enjoy capital gain benefits. This explains why sometimes financial buyers put a lot of money in highly leveraged companies. Their main goal in doing that is generating substantial equity returns.

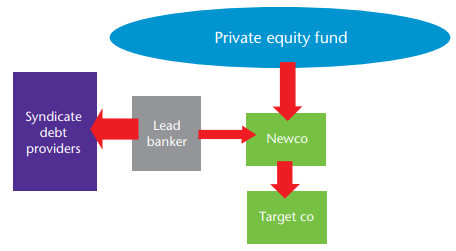

Structure

In a leveraged buyout, there is the establishment of a new company (Newco) that raises funds used for the acquisition of the target company. Figure two below summarises the structure of a leveraged buyout. A private equity firm or a private equity fund will usually contact a lead banker to provide the loan amount to acquire the target company. For the private equity fund to ensure a successful process, it will establish Newco, which serves as an investment vehicle in the acquisition process.

Notably, the funding of a Newco that acquires a target company is done using the private equity funds and the loan because banks never provide 100% of the needed finances. It is the bank’s way of reducing some of the risks involved in the acquisition process. For instance, in case the target company is overvalued, the lead banker will not be highly inconvenienced if it reaches a point where it must sell the target company’s assets to recover the loan amount. Even so, the debt that the bank provides is the so-called leverage because it gears up the investment deal.

For every successful LBO, the underlying investment return is highly amplified resulting in a significant increase in the private equity investor’s returns. However, the financial risk in underperforming LBOs can also be high. When a bank is extending a loan, it will usually assess the ability of the company to repay the loan. The bank will also compare the requested amount and the existing security as a way of lowering the risks involved in the deal. Although the use of a loan is convenient for the purchaser, it can lead to increased risks for various reasons.

First, the use of a loan puts pressure on the firm to achieve high revenues or returns. If the returns are not high enough, the LBO could underperform leading to numerous risks. One of the possible risks is the bank selling off the target company’s assets to recover the loaned amount since an underperforming acquisition cannot meet its instalment obligations. Thus, when structuring the leveraged buyout transaction, both the private equity fund manager and the banker involved should skilfully balance the risk-reward equation.

When looking at the structure of the leveraged buyout, it is important to note that two popular measures of leverage or gearing exist. The first one is “interest cover” and the second is “capital gearing.” Interest cover provides critical information about a firm’s ability to repay a loan whereas capital gearing looks at the total debt to total equity ratio for that investment. Low interest rates lead to one of two scenarios; the rising of interest cover (with constant capital gearing) or an increase in the total amount of borrowed money.

Economic Role, Advantages, and Disadvantages

Leveraged buyouts play important economic roles. One of them is that they increase employment opportunities. This is also one of the advantages of LBOs; job opportunities are beneficial to many. With LBOs, there is a change of ownership of a company and this leads to various job opportunities. LBOs also require specialised management to supervise the process. Although an existing management group can be used, a specialised team is often created from scratch leading to new employment opportunities. Leveraged buyouts also increase creativity and innovation, which often lead to positive economic changes. The main disadvantage of an LBO is that they take time to complete. The negotiation process and the loan acquisition process takes time.

Management Buyouts (MBOs)

A management buyout is another form of private equity transaction. In it, an existing management team purchases the business it supervises. MBOs often start with an expression of interest in the business by the incumbent management team. The team will approach the business owners and propose to buy the company from them. Once the owners have accepted the proposal, the incumbent management team will approach financial institutions to provide the needed funding for the completion of the deal. Management buyouts can happen when the management team feels like it is not receiving enough support from the owners of the company yet the business has great potential for profitability.

In some cases, a large organisation may have different divisions under the management of a group of specialised investors. In such a case, complexities of large-scale operations may happen, and the organisation may seem to neglect some of its divisions. Realising that the division they currently manage is an important source of revenue, the incumbent may approach the owner with the proposal to buy it out instead of letting it underperform.

Although an MBO is a welcome idea, the management, while initiating the buyout, must be careful not to breach any terms in its agreement with the business owner. For example, when originating the idea to buy the business it currently supervises, the management must be careful not to breach any confidentiality duties it owes to the employer. In other words, the management team should have a valid reason for wanting to buy the business and they should never reveal the tread secrets of the business to potential financiers in a bid to secure funding.

The management team should also be careful not to breach the service contract it entered with its employer. When it comes to MBOs, people are always concerned that the management can become increasingly interested in the purchasing to the extent that it fails to devote all its energies to the target company’s business. A management obsessed with the purchase will spend a considerable amount of time, money, and energy pursuing the buyout, and this could lead to a performance breach.

Not always do the management originate the idea to own the business they currently control. Sometimes, the owner may wish to retire or to give up ownership of the company in pursuit of other personal interests. In the process, the business owner or vendor may want to allow the current management to own the business since they understand what it entails and have participated in its management.

The owner will go ahead to encourage the managers to fund the buyout with any available preferred model. The usual approach is for the managers to get some money from their own pockets and the balance from a lending institution. It is always important for buyers to meet part of the purchasing cost with their private cash as this gives them enough incentive to grow the company; it makes them feel like the genuine owners of the company. However, there is no guarantee that the management will always be willing to buy a business they currently manage; value will be a key factor influencing this decision.

Mechanics

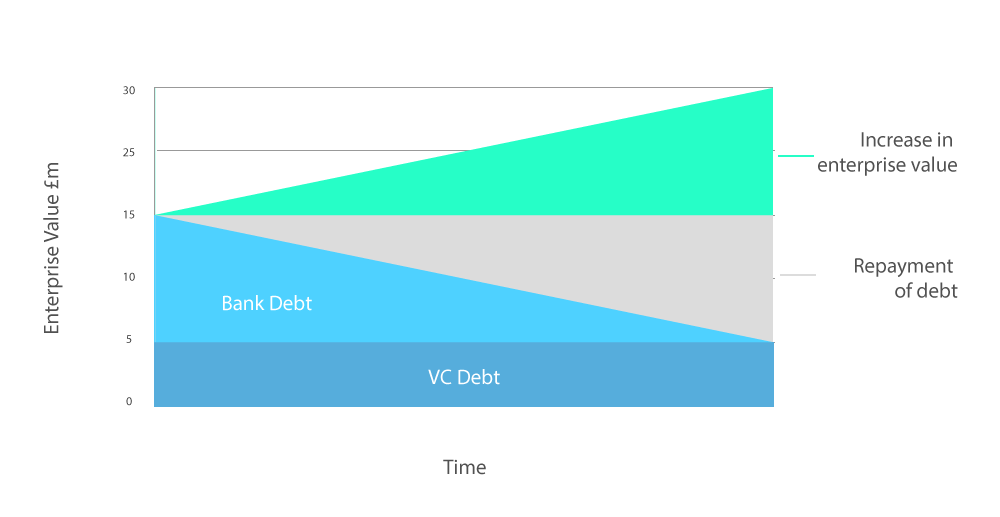

MBOs lie at the intersection of two classes of transactions and corporate law considers the two classes of transactions special. The first one is that MBOs are conflict transactions, which means that senior management has a fiduciary duty to maximise sell-side shareholders’ value. Since the management team will not usually have enough resources to buy the company at once, it will resort to getting a loan from a willing financial institution. Figure 3 below shows how the management of a company could use debt buying to acquire the company it manages. As shown in Figure 3, the acquisition process may take time, and this usually puts some pressure on the investors. Once the management has acquired the business, it will have to find a way to simultaneously repay the loaned amount plus interest while ensuring that enough money remains to facilitate daily operations and continuous value acquisition. Such a move will ensure the survival of the acquired company.

Although the expected new owners of a business undergoing management buyout are well-known, the MBO process begins with the appointment of a lead advisor. The lead advisor usually has enough experience in financial management and his or her role would be to assist the management throughout the drafting and the signing of the final deal. While a lead financial advisor is costly to procure, his or her services are inevitable.

Thankfully, the management and the company can sometimes split the associated cost. For instance, depending on how trusting the management and the company are, they could choose one person to serve as the lead financial manager since both the manager and the management need financial advice services. The lead manager could then appoint a special task force that handles the issues surrounding the MBO deal for both sides. This approach will significantly reduce the cost of the lead financial advice services.

Some of the functions of the lead financial advisor include the objective evaluation of the deal, handling all negotiation issues, providing advice concerning funding options, and managing the project from start to completion. The lead adviser will also prepare an information memorandum (IM) that overviews the company. Notably, most IMs serve as a marketing document. However, marketing is not that important because the potential buyers already know what they are going to buy because they have been managing that business.

Thus, an IM is just a marketing formality that could be presented to potential funders to expedite loan processing. Also, it is a legal requirement for companies to present IMs in some cases. For example, if the potential investors are in more than 20 countries, then the law in some countries requires that the target company presents IMs to all investors. This is especially the case when the idea to sell off the company comes from the owners (and not the managers).

Structure

As noted earlier, MBOs are structured such that the incumbent management becomes the new owner. The structuring idea may originate from the managers or the owners. For example, if the owner decides to sell the business at a low deal price, the management may become interested in buying the undervalued company. The management may also express an interest in buying the business if they feel they do not get enough support from the owners.

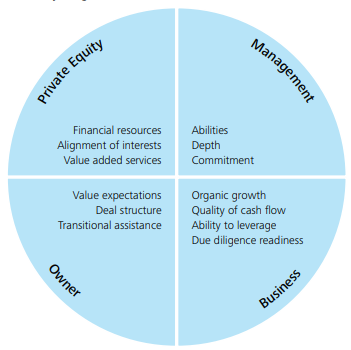

The lack of a succession plan among the owners of a company can also necessitate a management buyout. The parties involved in the buyout include private equity, management, business, and owner. Each of these parties has different interests in the deal as summarised in Figure 4 below. For example, the private equity firm is interested in financial resources and the alignment of interests among other things. For there to be a successful buyout, four critical conditions must be met; they are all-star management team, strong cash generation (through the target company), due diligence, and private equity.

Financial problems sometimes push the management to welcome outside bidders to own the company. The main problem that this approach provides is the information asymmetry problem. Information asymmetry refers to the fact that the management understands the company more than the third-party bidders, and this leads to the winner’s curse problem. That is, if the third party wins the bid, then it means that they paid more for the company than they could have.

Otherwise, their bid would not have been accepted. If the third-party bidder does not win the bid, it means that they have spent their valuable time, money, and other resources with nothing to show for it at the end of the day. Thus, in the case of an MBO, outside bidders lack an edge and are often at a disadvantage relative to the management (i.e., the inside bidder). For this reason, most outside bidders will refrain from participating in an MBO deal as this is the surest way of avoiding the winner’s curse.

Economic Role, Advantages, and Disadvantages

Like other private equity transactions, MBOs contribute to economic development in various ways. First, they ensure the continued existence of business organisations. This is also their most important advantage. Another advantage is that they allow for business continuity. MBOs give business owners a reliable exit plan from the market. The business owner will get paid for what the business is worth, and it will surrender ownership to the purchasers, who will ensure that the business continues to be in existence and that it achieves new value. Thus, the company will continue offering the services that it did before the sale, contributing continuously to economic development. MBOs also create numerous job opportunities.

For instance, the business owner and the business management will hire financial experts, legal teams, and other professionals to facilitate the creation of a reliable deal. The additional team members will get well-paying jobs, especially for the successful supervision of the creation of a deal. In some cases, the work involved in the MBO is a lot such that the assembled team will need to recruit more people to ensure the completion of the process on time and without significant issues. The main disadvantage of the MBO is that they lead to the winner’s curse whereby outside bidders stand no chance of winning a fair deal. Were it not for the winner’s curse, raising money for the MBO would be easier.

Institutional Buyouts (IBOs)

An institutional buyout is another common form of private equity transaction. It refers to the process by which an organisation acquires controlling shares in another company. The buyout can involve a private company, which leads to a “going private” kind of transaction. The institutional purchaser could be a venture capital firm, a private equity firm, or a commercial bank. In the case of institutional buyouts, a private equity provider creates, independently, a Newco that it uses to acquire the target company.

Usually, the private equity firm will give the management of the target company some stake in the company. The offer will be given to the management either as soon as the Newco acquires the target company or at some other time. The offer is usually intended to incentivise the management so that it works harder and creates more value for the business. After the acquisition, the private equity firm has the option of maintaining the old management or bringing a new one; it will depend on the firm’s assessment of the management and the prevailing business situation. Institutional buyouts are more commonly utilised in medium to large deals and secondary buyouts.

Institutional buyouts take when a private equity firm or a consortium of the same holds the controlling stake in a Newco. Therefore, institutional buyouts are different from start-ups where private equity funds hold a minority stake. In case a private equity fund takes the minority shares in a Newco, it will do everything possible to minimise the risks involved. For instance, the private equity firm will ensure it acquires veto rights over what the Newco does.

The private equity firm will also negotiate favourable terms that ensure none of its directors are dismissed, has a say in the appointment of new directors and can force an exit from the business. The idea is to ensure that the business is profitable and that the private equity firm can benefit from it. Protecting the appointed directors from any dismissal while maintaining the right to determine who serves in the Newco’s board of directors gives the private equity fund some powers in the Newco despite its minority stake.

Mechanics

The decision to purchase and run a new company in the case of an institutional buyout can be reached by the buyer and the seller (without involving the management team). However, all agreements that do not include the management team are deemed hostile, especially if the management has not agreed to the sale. The management plays an important role in the survival of an organisation, and its decisions and opinions about specific matters should not be ignored.

Also, while the institutional buyer has the option of retaining the current managers, most of them usually choose to create a new management team. The move to change the management of the acquired company is welcomed because it is one of the ways of instituting company-wide changes that will ensure that new value is achieved. After all, the buyout may have been influenced by a realisation that the company is not as productive as it could be. Thus, changing the management could be one of the many ways of stimulating improved performance within the organisation.

The private equity firm, or the purchaser of the target company, is responsible for restructuring the deal. The firm will determine, among other things, the most effective plan to exit the market and the best way to hire new managers. Even so, institutional buyouts do not apply to any company. That is, institutional buyers do not purchase any target company; they specialise in large corporations in specific industries. For example, institutional buyers will target companies that have unused debt capacity, companies that are highly cash-generative despite underperforming in their industries, companies with low capital spending requirements, and companies with stable cash flows.

In a buyout, the investor acquiring a company will consider disposing of its stake in a company by selling it to a strategic buyer or through an initial public offering (IPO). For an institutional investor, time is a critical aspect of the business. Thus, they have a limited time they target. Typically, they will consider five to seven years their preferred period, and they also create a plan for the transaction in terms of the planned investment return hurdle.

People can also refer to institutional buyouts as finance purchases or bought deals. In some of these deals, the management’s effort is critical to the achievement of success and growing the brand. For this reason, where the management of a company stays on even after the purchase, it is customary for the institutional owner to reward the managers with equity stakes through equity ratchets. The rewards are especially assured when the performance of the management is commendable. Thus, one of the things that make institutional buyouts different from management buyouts is how the management gains equity ownership in the target company.

In the case of an MBO, the management gains equity by being part of the bidding group whereas the management in the case of an IBO gains equity as a component of a remuneration package. Also, IBOs do not spark controversies as MBOs do because the management is not involved in the negotiation process. Also, the post-transaction equity ownership after an IBO resides in fewer hands, which means that the investors will be highly informed and incentivised to invest in monitoring management to protect their reputation as efficient promoters.

Structure

The structure of an IBO is almost like that of an MBO, the main difference being that in an IBO, the purchaser is an institution (not the management as in the case of an MBO). Therefore, the key players in an IBO include the institutional investor (usually a private equity fund/firm or a venture capital), the institutional investor’s lawyers, a private equity provider, the lawyers of the private equity provider, the bank, the lawyers of the bank, accountants, auditors, and investment bankers.

The different participants ensure that a deal is reached and that the deal is fair for all the participants in the group. It is the institutional investor that identifies a potential company to purchase and commence the negotiations. Usually, the institutional investor will go for a company that is on offer; it could be an entire company or a division of a large corporation. The negotiations between the institutional investors and the owners of the target company are the most important phase in the acquisition process. A deal can be reached after the owner has agreed to the offer on the table.

The lawyers ensure that the deal is within the law. They guide their respective clients about the best way to go about fulfilling the conditions of the deal. The lawyer also interprets the terms and conditions of the transaction and offer their clients appropriate advice. It is important that the participants respect the terms of the deal to avoid legal action being taken against them. It is also during this negotiation period that the buyer will determine whether to retain the old management or to create a new one.

Retaining the old management is advantageous because the owner will not have to go through the arduous process of looking for new supervisors. Another advantage is that the existing management possesses relevant experience that allows it to conduct daily operations with ease. If the new owner creates a new management team, it will have to give that team some time to familiarise itself with the company and how things are done there. The main disadvantage of retaining the old management is that it maintains the firm’s status quo.

It is also difficult for the new owner to restructure the company with the old management in place. If the new owner desires some change, altering the company’s management is necessary. Once the institutional buyer has decided about the management, it will create a compensation package for it. For it to incentivise the players, the management may need to provide equity to them. Notably, some of the money used in the acquisition of the target company will come from a lender, which could be a commercial bank.

Economic Role, Advantages, and Disadvantages

The main advantage of IBOs is that they involve large organizations. For this reason, no cash limit exists. IBOs also have a significant economic role. The first one is employment. As an institution embarks on a journey to purchase an identified organisation, it will create numerous job opportunities for different professionals. For example, lawyers, financial advisers, and institutional bankers will have an opportunity to work for the company and to ensure that the deal is sealed successfully. The deal will ensure that the business will continue being in operation, which is an important economic stimulus. In most cases, when it reaches a point where a company wants to sell off, it is because its performance has dwindled and that it could use a little assistance from an experienced team.

Therefore, an IBO prevents an organisation from imminent collapse, which means that the move saves thousands of jobs, directly and indirectly. The actual number of jobs saved by an IBO will depend on the size of the company. IBOs also make businesses more successful because they remove service and product duplication. Apart from that, an IBO gives managers a good offer as a remuneration package. The offer stimulates the management and encourages them to create more value for the company, which leads to economic development. The main disadvantage of the IBO is that it focuses on specific industries only. Therefore, not everyone can benefit from it.

Conclusion

Different types of private equity transactions are in existence today. The transactions help individuals to invest in a sort of indirect manner. Leveraged buyouts are the most common types of private equity transactions. They are effective and convenient because the buyer will use debt to finance most of the purchase. The assets of the target company will serve as the collateral for the loan, which means that the target company contributes something to the deal. The new owners will use some individual equity to make sure that they have a real connection to the company and a motivation to grow it. A management buyout is another common type of private equity transaction.

In this type of deal, the incumbent management of a firm takes over the ownership of that company. The management may originate the idea to own the company (if they feel the current owner is not committed enough). In other cases, the current owner may suggest to the management to buy the company, especially when the owner lacks a succession plan. The third form of private equity transaction is IBO. It involves organisations buying other organisations in specific industries. The three transactions have important economic roles.

References

Achleitner, Ann-Kristin and others, ‘Private equity group reputation and financing structures in German leveraged buyouts’ [2018] Journal of Business Economics 363.

Ahlers, Oliver and others, ‘Opening the black box: power in buyout negotiations and the moderating role of private equity specialization’ [2016], Journal of Small Business Management 1171.

Bertoni, Fabio, ‘Innovation in Private Equity Leveraged Buyouts’ [2017]. Web.

Berry, Dean F and Sebastian Green, Cultural, structural and strategic change in management buyouts (Springer 2016)

Bhattacharya, Ananyo, ‘The buyout’ [2015] Nature 400.

Bloom, Nicholas, Sadun, Raffaella and Van Reenen, John, ‘Do private equity owned firms have better management practices?’ [2015] American Economic Review.

Braun, Reiner, Crain, Nicholas, and Gerl, Anna, ‘The levered returns of leveraged buyouts: The impact of competition’ [2017]. Web.

Buchner, Axel and Kuffner, Markus, ‘Diversification Benefits of Private Equity Funds-of-Funds’ [2015] Private Equity: Opportunities and Risks 290.

Caselli, Stefano and Negri, Giulia, Private equity and venture capital in Europe: markets, techniques, and deals (Academic Press, 2018).

Cavagnaro, Daniel R and Yingdi Wang, ‘Institutional Investors’ Investments in Private Equity: The More the Better?’ [2019] International Journal of Business.

Cavagnaro, Daniel R, Berk A. Sensoy, Yingdi Wang, and Michael S. Weisbach, Measuring institutional investors’ skill from their investments in private equity (National Bureau of Economic Research 2016).

Chava, Sudheer, Wang Rui and Zou, Hong ‘Covenants, creditors’ simultaneous equity holdings, and firm investment policies’ [2019] Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis.

Daniels, Kenneth and Demissew Diro Ejara, ‘The Impact of Private Equity Sponsors on Syndicated Loans’ [2016] Quarterly Journal of Finance & Accounting.

Davis, Steven J, John Haltiwanger, Kyle Handley, Ron S. Jarmin, Josh Lerner, and Javier Miranda, ‘Private Equity, Jobs, and Productivity: Reply to Ayash and Rastad’ [2018] Harvard Business School Entrepreneurial Management Working Paper 18.

Dionne, Steven S., David Sinyard, and Karen D. Loch, ‘Fast Thinking in Private Equity: The Role of Heuristics in Screening Buyout Opportunities’ [2018] Academy of Management Proceedings.

Droussiotis, Chris,‘Leveraged Buyouts (LBOs): The Financial Engineering of Transactions and Evolution of LBOs’ [2019] Mergers & Acquisitions: A Practitioner’s Guide To Successful Deals.

Eisenthal, Yael, Peter Feldhuetter, and Vikrant Vig, ‘Leveraged buyouts and credit spreads’ [2017] London Business School 56.

Faccio, Mara and Hung‐Chia Hsu, ‘Politically connected private equity and employment’ [2017] The Journal of Finance.

Fang, Lily, Victoria Ivashina, and Josh Lerner, ‘The disintermediation of financial markets: Direct investing in private equity’ [2015] Journal of Financial Economics.

Graziani, Marco ‘Fiscal Treatment of Leveraged Buyouts’ [2016] The Economics of Leveraged Buyouts.

Groh, Alexander, Heinrich Liechtenstein, Karsten Lieser, and Markus Biesinger, ‘The Venture Capital and Private Equity Country Attractiveness Index 2018’ [2018] Journal of Technology.

Haddad, Valentin, Erik Loualiche, and Matthew Plosser, ‘Buyout activity: The impact of aggregate discount rates’ [2017] The Journal of Finance.

Hammer, Benjamin, ‘Buy-and-Build Strategies and Buyout Duration: Evidence from Survival-Time Treatment Effects’ [2018] SSRN 2819995.

Hege, Ulrich, Stefano Lovo, Myron B. Slovin, and Marie E. Sushka, ‘Divisional buyouts by private equity and the market for divested assets’ [2018] Journal of Corporate Finance.

Hooke, Jeffrey and Ken Yook, ‘The relative performances of large buyout fund groups’ [2016] The Journal of Private Equity.

Hooke, Jeffrey, Ken C. Yook, and Stephen Hee, ‘The Performance of Mostly Liquidated Buyout Funds, 2000-2007 Vintage Years’ [2016] SSRN 2718473.

Howorth, Carole Mike Wright, Paul Westhead, and Deborah Allcock, ‘Company metamorphosis: professionalization waves, family firms and management buyouts’ [2016] Small Business Economics.

Jarrad Harford, Jared Stanfield, and Feng Zhang, ‘Do insiders time management buyouts and freezeouts to buy undervalued targets?’ [2019] Journal of Financial Economics.

Jelic, Ranko, Zhou, Dan, and Wright, Mike, ‘Sustaining the buyout governance model: inside secondary management buyout boards’ [2019] British Journal of Management.

Jenkinson, Tim and Miguel Sousa. ‘What determines the exit decision for leveraged buyouts’ [2015] Journal of Banking & Finance.

Jenkinson, Tim, Robert Harris, and Steven Kaplan, ‘How do private equity investments perform compared to public equity?’ [2016] Journal of Investment Management.

Jenkinson, Tim, Wayne R. Landsman, Brian Rountree, and Kazbi Soonawalla, ‘Private equity net asset values and future cash flows’ [2019] SSRN.

Kamoto, Shinsuke, ‘Managerial innovation incentives, management buyouts, and shareholders’ intolerance of failure’ [2017] Journal of Corporate Finance.

L’Her, Jean-François and others, ‘A bottom-up approach to the risk-adjusted performance of the buyout fund market’ [2016] Financial Analysts Journal.

Louise, Scholes, ‘Buyouts From Failure’ [2018] The Routledge Companion to Management Buyouts.

Mao, Yaping, and Luc Renneboog, ‘Do managers manipulate earnings prior to management buyouts?’ [2015] Journal of Corporate Finance.

Marini, Vladimiro, Massimo Caratelli, and Ilaria Barbaraci, ‘Corporate governance, the long-term orientation and the risk of financial distress-evidence from european private equity backed leveraged buyout transactions’ [2019] Piccola Impresa/Small Business.

Nadauld, D Taylor and others, ‘The liquidity cost of private equity investments: Evidence from secondary market transactions’ [2018] Journal of Financial Economics.

O’Brien, Timothy, ‘Understand need for specificity of buyout arrangements in assistant coaching contracts’ [2017] College Athletics and the Law.

Reddy Kennedy, En Xie, and Yuanyuan Huang, ‘Contractual buyout-a legitimate growth model in the enterprise development: foundations and implications’ [2016] International Journal of Management and Enterprise Development.

Renneboog, Luc and Vansteenkiste, Cara ‘Leveraged buyouts: Motives and sources of value’ [2017] Annals of Corporate Governance 291.

Renneboog, Luc and others, ‘The routledge companion to management buyouts’ [2018] The Routledge Companion to Management Buyouts.

Robinson, David T and Berk A. Sensoy. ‘Cyclicality, performance measurement, and cash flow liquidity in private equity’ [2016] Journal of Financial Economics.

Smith, David C, ‘The Importance of Leveraged Lending: It’s (Not) All Academic’ [2016] SSRN 2726235.

Spagnolo, Stefano and Antonio Corvino, ‘Leveraged Buyouts (LBOs) in the Private Equity Industry: the Role of Debt and Financial Structure as Drivers for the Value Creation of the Fund’s Investors’ [2016] University of Pisa.

Stafford, Erik, ‘Replicating private equity with value investing, homemade leverage, and hold-to-maturity accounting’ [2017] Homemade Leverage, and Hold-to-Maturity Accounting 21.

Stringham, Edward, and Jack Vogel, ‘The leveraged invisible hand: how private equity enhances the market for corporate control and capitalism itself’ [2018] European Journal of Law and Economics.

Subramanian, Guhan, ‘Deal Process Design in Management Buyouts’ [2016] Harvard Law Review.

Weisbach, Michael S, ‘Measuring Institutional Investors’ Skill from Their Investments in Private Equity’ [2016] Management and Finance Journal.

Wright, Michael and John Coyne, Management buy-outs (Routledge 2018).

Wright, Mike and Kevin Amess, ‘Management Buyouts (MBO s)’ [2015] Wiley Encyclopedia of Management.

Wright, Mike and others Management Buyouts: An introduction and overview (Routledge 2018).

Wright, Mike and others, Management Buyouts: The history of an organizational innovation (Routledge 2018).

Wright, Mike and others, The Routledge Companion to Management Buyouts (Routledge 2018).

Yan, Alperovych, ‘The Impact on Productivity of Management Buyouts and Private Equity’ [2018] The Routledge Companion to Management Buyouts.

Young, Allan William, ‘How to Retreat: The Necessary Transition from Buyouts to Leasing’ [2018] Coastal Management.