Byzantine civilisation is a major part of world history and culture. ‘Byzantium’ is the name describing both the state as well as the culture of the Eastern Roman Empire in the middle Ages. It was an extension of the Roman Empire in the east, being called ‘Eastern Roman Empire’ because it governed over the eastern part of the empire. Being a large multi-ethnic Christian state founded on a system of urban centres and protected by a strong and skilled mobile army, the Byzantine Empire preserved the most important foundations of the Late Roman Mediterranean civic culture.

Historians are nearly unanimous in claiming it began in the year 330 A.D when then Roman emperor Constantine the Great decreed that the Roman capital be shifted from Rome to Byzantium, which he renamed as Constantinople. The Byzantine Empire lasted until the year 1453 A.D, its end coming when the Turks conquered Constantinople. The Turks went on to rename Constantinople as Istanbul.

Byzantine art was the peculiar style of Eastern Orthodox Christian art that developed and sustained steady growth during the period of the Byzantine Empire. Although the empire historically began in 330 A.D, Byzantine art became distinctly apparent only in 500 A.D during the rule of emperor Justinian. Byzantine works of art were created with basically two aims – to serve the Eastern Orthodox Christian religion, and to work for the imperial court. Byzantine artists were unnamed and unnoticed, either employed in the court or as members of the Orthodox Christian church.

The artists were not permitted to indulge in personal fancies but had to follow strict guidelines that controlled and influenced the content and pattern of all artistic works. The overall director of Byzantine art was the emperor in his role as the head of the government and the head of the national church.

Two cognitive artistic traditions had a pronounced effect on Byzantine art: Early Christian and Classical traditions. Early Christian tradition, heavily influenced as it was spiritually, favoured art forms that had flat, two-bodily form or proportion figures created from patterns existing only in the mind and separated from embodiment, mainly to stress on their holy nature. Classical tradition was totally founded on early art of the Romans and Greeks. It was based on tangible and earthly reality; this emphasis was apparent in the art creations that featured fully modelled, natural looking lifelike images drawn as a result of measured and objective assessment.

The Byzantine Empire is famous for its unique churches, magnificent structures, some of whom still survive. Byzantine churches were constructed out of brick and mortar. The façade was plain and exposed, meant to symbolise the outside world. The interiors were grandly decorated with magnificent colourful murals depicting religious figures and scenes meant to symbolise the ideal or spiritual world.

The outstanding feature of Early Byzantine churches was the square central bay overlooked by a majestic dome that was sustained by massive arches built on four pillars. Galleries and aisles were constructed around the bay, which is essentially an open area between pillars. The area around the altar, which is the most sacred part of the church (called its ‘sanctuary’), was positioned east of the bay with three semicircular recesses called ‘apses.’ The sanctuary was partitioned from the rest of the church by a tall screen called ‘iconostasis.’

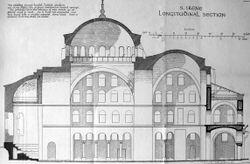

Priests conducted services for the public from the sanctuary, while the people were positioned in the galleries and aisles. The fundamental structure of the church involved a combination of a horizontal and vertical axis within one supporting structure; the former extending from the sanctuary to the west entrance, and the latter formed by the central dome. The outstanding example of such a horizontal and vertical axis combination is Istanbul’s Hagia Sophia.

Hagi Sophia (Church of the Holy Wisdom) was dedicated on Christmas Day, 537 A.D, as a replacement of the church dedicated in 360 A.D which was destroyed during the Nika riots of January 532 A.D. The church, which continues to stand as one of the greatest achievements of world architecture, drew such admiration as ‘the perfect church,’ that it completely changed Byzantine imagination. It’s design, which maintained a longitudinal axis but was overlooked by its huge central dome, was intended to depict the church as a picture of the world with the dome of heaven hanging above, from which the Holy Spirit came down during the liturgical rites.

Centuries later, just before the Turks captured Constantinople in 1453, George Sphrantzes wrote of it, “that most huge and all-holy Church of the Wisdom of God, that Heaven upon earth, throne of the glory of God, the second firmament and chariot of cherubs, the handiwork of God, a marvellous and worthy work, the delight of the entire earth, beautiful and more lovely than the beautiful.”

Another outstanding example of Early Byzantine architecture is Hagia Irene in Istanbul.

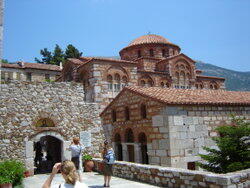

Later Byzantine architecture was not as large and extravagant as featured in the earlier period. Later Byzantine architects developed a new plan called ‘cross-in-square,’ whereby churches featured four corner bays (symbolising the four arms of a Greek cross) with arched roofs, positioned at 90 degrees to one another, which opened out from the central bay and dome. Domes were constructed over each corner bay. The high structures that supported the central and corner bay domes, called ‘drums,’ had many windows. Churches built during this period also have a little exterior decoration. A famous exponent of Later Byzantine ‘cross-in-square’ architecture is Hosios Lukas in Greece.

Later Byzantine art was modified in the centuries that followed in regions like Russia, Serbia, Armenia and Italy, where architects changed the Byzantine pattern to suit their building materials, technical methodology and climatic conditions.

A persistent characteristic of Byzantine art and architecture of all periods was the mosaics and frescoes that featured in the interiors of all Byzantine churches. Mosaics are small pieces of glass joined together to shape a pattern or picture. Such glass, called ‘smalti,’ consists of thick sheets of special coloured glass characterised by an abrasive surface and the presence of little air bubbles in its interior. Byzantine mosaics reflect a strong use of colour with images having large eyes, appearing stiff and flat and seem to be floating.

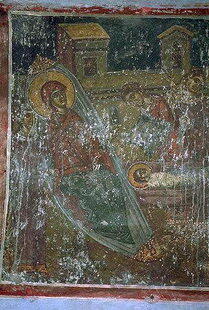

Frescoes are wall paintings drawn on wet plaster.

The frescoes reflected the belief of Byzantines that emperors and saints were special attendants of God because they were depicted as solemn, bearded men who wore lavishly jewelled robes and carried elaborately decorative jewelled items.

The frescoes also depicted the theme of torment and mutilation, reflecting the Byzantine belief that is morally and ethically better to mutilate prisoners rather than kill them.

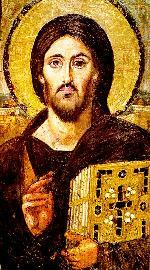

The church authorities organized the order of depicting religious pictures – Jesus Christ was given top rank, his portrait featuring in the central dome. Mary, the mother of Jesus, was given second rank, her portrait positioned at the top of the main apse. Third rank was given to the prominent scenes in the life of Jesus Christ, which were depicted on the central parts of the church walls and pillars.

The lowest rank was given to saints and church leaders, whose portraits were depicted on the lower parts of the church walls and pillars. Byzantine artists favoured the frontal view in their portraits against a background of gold mosaic or one colour of paint. The permission to allow Jesus Christ to be painted emanated from the fact that He chose to take the form of a human being in order to save mankind.

Unfortunately, very few frescoes and mosaics that were created before 800 A.D still exist, as most were ruined in the century preceding that period as a consequence of the ‘iconoclastic controversy’ when a segment of Christians called ‘iconoclasts’ were against adulation of such religious pictures in churches and forcibly removed or demolished the frescoes and mosaics.

In the period following the iconoclastic controversy, Byzantine mosaics and frescoes passed through three stages of development, each subsequent stage characterised by a slight and not obvious change in style. The first stage involved a stylishly graceful, controlled style that is best visualised in the church of Daphni, near Athens in Greece. The second stage involved a bolder, strikingly impressive style that can be seen in the Norman churches in Sicily, Italy. The last stage involved heightened feelings and emotions shown in story like account of a sequence of events that is well exemplified in the church of Kariye Camii in Istanbul, Turkey.

Apart from frescoes and mosaics, Byzantine art also developed panel pictures, book decorations, and Byzantines indulged in many crafts. Panel pictures, called ‘icons,’ are images considered holy and worthy of worship.

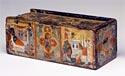

Icons are painted on pieces of wood and generally held in the hand during a religious procession. Book decorations involve drawing small pictures of scenes from the Bible in the margins of gospel and psalm books. Byzantines favoured small craftwork involved carving religious pictures on items like boxes plaques, crosses, crowns and vestments.

References

- Boguslawski, Alexander. “Byzantine Icons.” Rollins.edu. 2005.

- “Byzantine Architecture.” Wikipedia.org. 2007. Web.

- “Byzantine Art.” Artlex.com. 2007. Web.

- “Byzantine Art.” The World Book Encyclopedia. International ed. 1996. Vol 2, pp 696-699.

- “The Byzantine Empire.” Crystalinks.com. (n.d). 2007. Web.

- “Byzantium.” Fordham.edu. 1995. Web.

- Cormack, Robin. “Byzantine Art.” Oxford University Press: 2000.

- “Frescoes.” Crete Tour Net. 2007. Web.

- “The History of Mosaic Art – Mosaics in the Ancient World.” The Joy of Shards Mosaics Resource. 2007. Web.

- Tauna, Black. “The Byzantine World.” Members.tripod.com. 2000. Web.