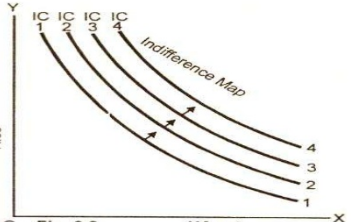

Income and substitution effects explain the unconscious and rational choices by consumers to achieve maximum utility of a product in comparison with another. In other words, they show how changes in income and purchasing powers influence consumers’ choices of commodities from which they derive maximum utility. Generally, consumers’ rationality depends on the market forces of price, demand and supply, and always dictated by personal tastes and preferences.

Tastes and preferences differ among individuals, but purchasing powers and relative prices or quality changes determine the consumer’s preference and substitution over a given period (Jensen & Miller 2007). Income effects evaluate the changes of the purchasing power due to the relative change in price of a commodity that impacts real income. Substitution effect evaluates the quantity bundle that a consumer prefers or the one that he/she derives equal utility after price changes (Pindyck & Rubinfeld 2013).

The substitution effect is a two-fold phenomenon dependent on price changes as it measures how much an increase or a reduction of the relative price encourages the consumption of other goods. In this case, income levels are constant. Thus, the analysis depends on the consumers’ rationality to derive maximum utility, despite the price changes that impact their purchasing powers (Lipsey & Chrystal 2011). Unlike the substitution effect, the income effect looks at how much changes in price would affect the incomes, purchasing powers and the overall demand.

In this case, Adam and Kim are students, and the analysis assumes that they have constant income. The fact that Kim is a vegetarian and that Adam likes chicken, though he considers it an inferior good, the analysis assumes that vegetables are substitutes to chicken and vice versa for this particular study.

Let v1 denote the price for vegetables, while c1 denotes the current price of chicken. Also, assume that at current prices, Kim consumes q1 units of vegetables, while Adam consumes q2 units of chicken. The fact that Adam considers chicken an inferior commodity, it implies that he can consume vegetables and derive the same utility. For Kim, he can consume the chicken, but considering its health impacts, he can only derive minimum utility or forego the meal. At this point, Kim and Adam will consume the following units of chicken and vegetables, assuming constant income and prices:

Price fall for chicken widens Adam’s scope of choices since he can comfortably eat chicken and experience consumer surplus, or he can stick to vegetables at the prevailing price. In this case, Adam can afford more units of chicken as the price falls, but taste and preference will determine the actual units consumed despite the price fall. Assuming c2 is the new price for chicken, Adam can afford q2+x units as compared with the initial q2 units. The fact that Adam considers chicken an inferior product, he can choose to buy fewer quantities of chicken, say q2-x, to derive the same utility, but with reduced income and purchasing power.

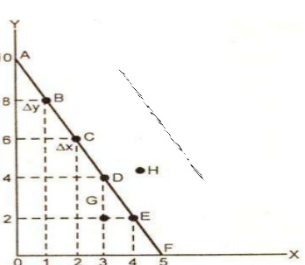

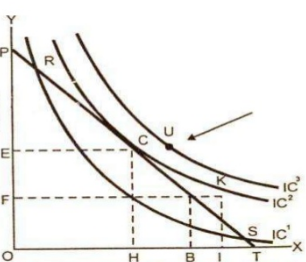

The substitution effect on Adam’s case will depend on his rationality for the reason that the reduced price means an increase in disposable income for chicken, and a constant income for vegetables. If Adam prefers chicken, the demand for vegetables will fall, while the demand for chicken will rise, and only changes in the price of vegetables will influence his rationality. To demonstrate the effects, Adam’s new budget line will represent levels of income that are tangent to the original budget line, whereby he can consume more units of chicken compared with those of vegetables. The substitution effect represents the movement from point B to a new point C in the Adam’s case.

At this new consumption level, the equilibrium is equal to the original consumption level, and the budget line is parallel and tangent to the initial indifference curve. Point C represents Adam’s choice in the event of a price reduction and simulates consumer surplus by holding the real income at a fixed level. In addition, considering the fact that Adam’s choice for chicken is inferior, the substitution effects assume a positive value with the price reduction or a zero, if he opts for vegetables despite the price fall. In Kim’s case, the substitution effect is insignificant for the reason that the difference between the original and new consumption levels is not price-dependent, but depends on other market factors and preferences (Goolsbee, Levitt & Syverson 2013).

A reduction in the price of chicken implies that Adam’s real income increases for the reason that he can afford more units of chicken consumed with the same level of income. That is, in real terms, he is better off compared with Kim, who with the fixed income level, can only afford vegetables despite a reduction in the price of chicken. In this case, the income effect represents the difference between the new intermediate consumption level D and the final consumption level C for Adam.

Alternatively, evaluating the income change necessary to move Kim to the new Adam’s consumption levels would denote the income effect, depending on normality/inferiority of chicken with regard to Kim. In other words, Adam’s substitution effect should reflect on Kim’s total effects of price changes, assuming that he prefers chicken at the worst situations. In this case, Adam’s choice to buy chicken due to the price fall represents an increase in consumer surplus, and by assuming perfect consumer rationality, the demand for chicken will rise when compared with that of vegetables.

With regard to Kim’s case, the substitution effect is insignificant compared with the income effect in that he maintains his purchasing power and real income despite the relative price change for chicken. Therefore, Kim’s indifference curve shows a declining demand for chicken irrespective of the price fall since there are few alternatives as a result of the income effect. In this context, income effect refers to the inflexibility of the income from the assumption that the students have a constant level of income.

For Adam’s case, income effects represent the equilibrium movement from point C to D, and depending with his rationality and market forces of the substitutes/vegetables, the effect can take positive or negative values. For example, if the price change compels Adam to consume chicken, the income effect would have a positive value, considering that it is an inferior product (Komlos 2014). To conclude, the income effect represents the total effects of price changes, whereby the substitution effect for Adam denotes the purchasing power, while the income effect for Kim denotes the inelasticity of price in relation to income.

References

Goolsbee, A, Levitt, SD, & Syverson, C, 2013, Microeconomics, Worth Publishers, New York, NY.

Jensen, RT, & Miller, NH, 2007, Giffen behavior: theory and evidence, National Bureau of Economic Research, New York, NY.

Komlos, J, 2014, Behavioral Indifference Curves, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, United Kingdom.

Lipsey, RG, & Chrystal, KA, 2011, Positive Economics, Oxford University Press, Oxford, United Kingdom.

Pindyck, RS, & Rubinfeld, DL, 2013, MGMT 405, Managerial Economics, Pearson Learning Solutions, Boston, MA.