Introduction

In spite of the global improvement of financial markets together with the reduction in the risks encountered by many economies after the global financial crisis of the 2008, the world economy is still expanding at a slow rate. However, United Nations (2013) anticipates, “after a marked down-turn over the past two years, global economic activity is expected to slowly gain momentum in the second half of 2013 and 2014” (p.1).

Throughout the recession, China managed to remain stable economically through subsidisation and deleveraging of its products. The effects were to make the Chinese products competitive in the international markets since subsidisation had the impact of lowering the prices of the products in the international markets (Heshmati 2012).

The Chinese GDP per capita is low compared to the income per capita for European nations and the USA. Amadeo (2012) puts the Chinese GDP per capita at $9,100 while GDP per capita for the US is $49, 800.

This means that China is able to have access to cheaper labour compared to the US. With these arguments in mind, this paper focuses on determining the impact on global trade in 2013 if China’s economy continues to exhibit slow or no growth in its GDP. It also investigates how Global Multi-National enterprises should prepare for such a scenario.

Impacts of China’s Economy on the Global Trade

Over the past two decades, China has undergone intense growth in GDP. This growth has relied principally on the boom in construction and manufacturing sector. However, as Halverson (2010) notes, this growth has been “fuelled by the surging real estate prices, and exhibiting all the classic signs of bubble” (p.93). China has experienced a rapid rise in credit through the government’s efforts to boost the production capacity while still maintaining China’s currency afloat.

Thach (2012) argues that the growth of credit in China takes “place not through traditional banking but rather through unregulated “shadow banking” neither subject to government supervision nor backed by government guarantee” (p.34). From an economic perspective, this means that an economic burble is almost bursting in China especially by noting that the GDP growth has become stagnant as from 2012, which is expected to remain at this state through 2014.

This situation poses an immense fear since it has provided all possible reasons for indication of economic and financial crises. China has emerged as a major global economic hub. Indeed, if the crisis is to occur, there is no doubt that the global trade will be affected as it happened in Japan in 1980 or America in 2007.

China’s economic crisis effects on the global trade are magnificent as evidenced by the striking growth of house consumption for China over the past two decades. Although it has been on the rise, it has lagged well behind the overall growth in the GDP. Currently, as Busakorn, Fung, and Hitomi (2009) reveal, “consumer spending is only about 35 percent of G.D.P., about half the level in the United States” (p.30).

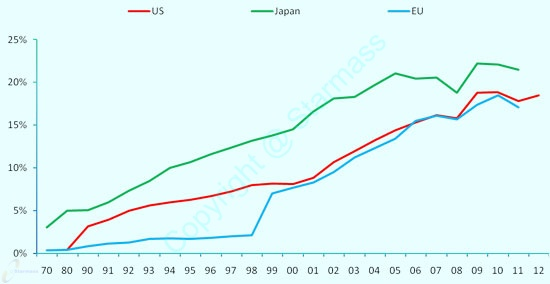

The question that arises is, ‘who purchases goods and services which are produced in China at low cost?’ China depends overwhelmingly on the rising trade surpluses in the effort to ensure that her manufacturing sector remains live and afloat. To keep its manufacturing sector afloat calls for heavy investment spending. This strategy has cost the country’s half of its GDP at the exchange of rapid growth of China’s export market as shown in fig.1 below.

As argued before, consumer demand is becoming relatively weak in China. Thus, the motivation behind large government spending in investments is questionable. Such spending is driven by a real-estate burble that is ever increasing. This provides a parallel scenario with the US’ economy in which, “as credit boomed, much of it came not from banks but from an unsupervised, unprotected shadow banking system” (Halverson 2010, p.95).

Hence, similar to the case of America in the past few years, financial systems are more vulnerable to risks than implied by conventional banking data in China. This vulnerability has obvious ramification on the global trade especially on the raw material in Europe and the finished products from the U.S.

China has had an immense demand for raw material to drive its production capacity. For instance, the demand of steel in China grew by 20 percent every year from 2005. In 2013, FT Reporters (2013) put this growth at 2 to 4 percent. This slowed growth means a lot to nations such as Australia, which ships most of its iron ore to China.

Reduced growth in demand for raw material means that nations from where China sources its raw material will have to look for alternative export markets. Hard economic times due to depreciation of the Chinese currency in comparison with the dollar could have the impacts of destabilising the global trade equation already established by China.

Despite the fact that China is experiencing slowdown in economic growth as measured by GDP index, in case of infrastructure coupled with investment spending hikes, demand for various capital goods and machineries will be affected. Since Germany is better in this field, it may gain an immense competitive advantage in the global market for these products. However, consumer oriented products such as electronics coupled with luxury goods are proving being more resilient.

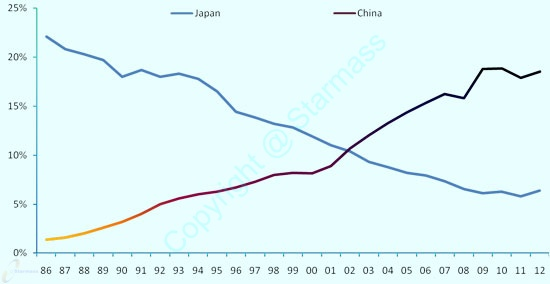

Nevertheless, weaker brands will be anticipated to suffer some loss. This may create a situation in which the American-produced finished products will peak up in the global market again. As shown in fig.2, China’s share in imports in comparison to Japan has been in inverse proportion since imports from the US have been on the rise in case of China.

Based on the above graph, it is evident that China surpassed the capacity of Japan to import from the US. In fact, China has been pursuing the low-cost strategy to drive the success of its manufacturing sector. China has also emerged as the biggest single importer from the EU.

This situation creates an immense uncertainty on how changes in economic status of China will play into shaping the import and export markets for both the EU and the US, which are already experiencing problems associated with high costs of labour often resorting to outsourcing manufacturing in China.

In support of this argument Heshmati (2012) informs, “China does a lot of manufacturing for businesses, including the US companies” (p.27). Most of the imports shipped into China comprised raw materials that are used by the Chinese-based manufacturing companies to make final products on behalf of the foreign-based firms, which are often global companies.

Most of the products exported to the US by China are essentially finished goods that are destined for American consumers via American contracting companies. These exports include “electrical equipments and computing and data processing gadgets while not negating the optical instruments” (Quélin & Duhamel 2003, p.649). Raw materials imported include oil, organic chemical fuels, and even metal ores mainly from Latin America amongst some African nations.

This implies that, in case of negative impacts on the Chinese economy so that its manufacturing capability is slowed, the pain will be felt globally. Since the demand for products and services produced in China will remain on the rise as global population continues to rise, dwindled manufacturing capacity of China will mean sourcing alternative places to manufacture products that are in demand.

The EU and the US have this capacity, but labour costs are prohibitive since they result in higher-priced products (Harland, Knight, Lamming & Walker 2005).

Hence, if the manufacturing trend shifts in favour of the U.S. and the EU, which have high GDP per capita and high labour costs, consumer product prices will go up globally. In fact, any negative impacts on the export of the Chinese-made products will have a cumulative negative impact on imports of raw material from the US, the EU, and other places where China sources its materials.

The weakening of Chinese currency would establish a different equation of financial markets in the US. China “is the largest foreign holder of the US treasury bills, bonds and notes, and owned $1.264 trillion treasuries by January 2013” (FT Reporters 2013, p.18). China purchases debts of the US in the effort to support the value of the Dollar. It also ensures that Yuan’s value remains well below the Dollar so that export prices remain competitive.

However, even though competitiveness of exports is not favourable for China under such circumstances, having sourced material from the US, converting them into finished goods, and then shipping them back, in overall, China becomes a major gainer in the balance of trade.

With this advantage combined with China’s roles in the American banking industry, China gets adequate advantage. This creates more uncertainties in the precise determination of how the Chinese economy will shape up following the almost-stagnant growth in GDP that is experienced in the last quarter of 2012 and in 2013.

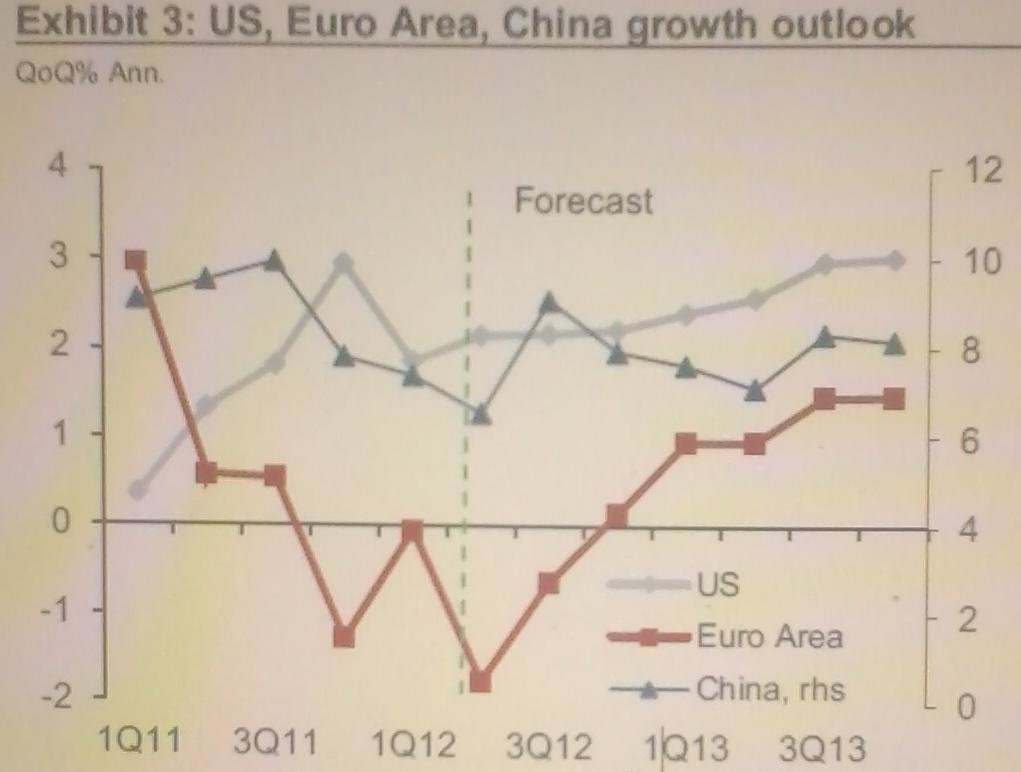

According to Credit Issue (2012), China’s growth curve currently assumes the L-shape. Even though the Credit Issue (2012) forecasted growth of China at 7.7 percent in 2012 and 7.9 percent in 2013 after having reviewed these figures from 8.0 percent and 8.2 percent respectively, the authors believe that, when adjusted on a quarterly basis, the growth has the possibilities of slowing down by 6.6 percent.

For global multinational organisations that seek to seize an opportunity to take up the vacuum created by the reduction in dominance of China in the global markets, these forecasts provided a room for such organisations to put in place strategies for producing products for the global market consumption that are competitive to those produced in China.

According to Credit Issue (2012), “China will be in a weak growth cycle (weak only by its own past standards, that is) for the next several years, featuring a weak credit cycle, a weak export cycle, and a weak property cycle” (p.10). Figure 3 shows this performance of the China’s economy. The next section investigates how global multinational enterprises will respond to the challenges in a continued growth that are being exhibited by China.

How Global Multi-National Enterprises should prepare for such a Scenario

From discussions in the above sections, it was argued that many multi-national companies outsource manufacturing from China and other Asian nations. Any negative impacts on the manufacturing capacity of China will have obvious consequences on these multi-national enterprises in terms of development of new trade and business policies that will ensure that their products will remain relevant in the markets.

China has been the most preferred destination for NAFTA and the EU-based multi-national companies seeking to lower their production costs owing to low labour costs in China. However, with the slowed economic growth and the rising value of the China’s currency in relation to the dollar, multinational companies are finding it difficult to continue operating in China.

For instance, by enumerating rising labour costs, quality production challenges, and the increasing number of multi-national companies in the EU are shutting down their productions in China. Examples of such companies include Steiff and Eriksson. NAFTA multi-national organisations such as Nike and Apple report a similar experience (Harriott, Hatfield & Walker 2007).

Research by various scholars and CEOs of organisations on outsourcing operations in China confirms that there is a need to close operation in China due to the rising costs. For instance, Anzeige (2008) quotes Steiff’s CEO, Martin Frenchman, complaining about the challenges encountered by focusing on outsourcing manufacturing in China.

According to the CEO, there is a rising cost of labour since many companies seek to outsource their operation in China. According to Pricewaterhousecoopers, this rise is due to the hiking inflation rates, which average to about 20 percent (Anzeige 2008, Para.5).

Faced with a situation where multinational organisations have to consider various alternative ways of producing cheaply to remain competitive in the international markets, consideration is being made on outsourcing production. In fact, even China is outsourcing manufacturing to other places where labour supply is still in excess. This assertion is evidenced by Anzeige who claims, “Someone who just wants to produce T-shirts is more likely to go to Vietnam or Africa” (2008, Para.7).

Centre for American Progress (2013) further argues that NAFTA-based global organisations also find it hard to continue with outsourcing manufacturing services in China since there is increasingly high demand for raw materials such as fuels together with rising costs of shipping. The labour cost difference between the US and China has reduced nearly by a half over a period of 8 years anticipating settling at steady state of 16 percent (Krugman & Obstfeld 2006).

Factoring in other costs that are associated with outsourcing manufacturing, the economic justification for NAFTA and the EU-based multi-national firms to outsource to China is invalidated. This implies that such companies would perform better financially in terms of cost saving if they relocate their production back home. However, this would lead to loss of jobs in China and a corresponding increase in employment rates for the EU and NAFTA.

From the above arguments, it far better if Apple, Nike, Steiff, and Eriksson hold their strategic decision to relocate their production back home until a sufficient number of firms has relocated.

This move is perhaps an incredible strategy for success since the organisation would take advantage of the likelihood of higher labour supply if other firms relocate their manufacturing elsewhere. The economic situation in China also remains unclear, as it is not yet known concerning the strategies that the government needs adopt to ensure that China’s economy does not shrink as it did during the 2008 recession, which massively influenced the US and the EU.

Conclusion

China has been experiencing growth in GDP in the range of double digits over the last few decades. The sustained growth has decreased from the last quarter of 2012. This trend has also been observed in 2013 making it hard to determine the economic situation of China in the near future as projected before by GDP growth forecast parameters.

The paper notes that there is an increasing cost of production in China since labour costs have been rising due to the demand for outsourcing in the country by many multi-national organisations. Combined with the dwindling value of the Chinese currency, this makes China uncompetitive to outsource.

Since the export of finished goods that are made from raw materials from contracting firms’ nations drive China’s economy, this paper forecasts that the increasing costs in China will lead to low exports. Hence, the GDP of the country will continue to stagnate. Such a situation is not attractive to Apple, Nike, Steiff, and Eriksson, which have been relying on cheap labour costs in China to produce their products that are meant for consumption in their nations and other places across the globe.

References

Amadeo, K 2012, ‘China’s economic and impacts on the global trade’, Economic research, vol. 3 no. 4, pp. 214-219.

Anzeige, N 2008, When Outsourcing Fails: One in Five German Firms Leaving China. Web.

Busakorn, C, Fung, M & Hitomi, K 2009, Foreign Direct Investment in East Asia and Latin America: Is There a People’s Republic of China Effect?, American Development Bank Institute, paper No.17, London.

Centre for American Progress 2013, Overseas Outsourcing: Trend Continues to Grow as American Workers Suffer, Centre for American Progress, New York.

Credit Issue 2012, ‘The slow get slower: so do most of the rest’, Economic research, vol. 2 no.1, pp. 1-36.

FT Reporters 2013, ‘Global economy: When China Sneezes’, Financial Times, vol. 1 no. 1, pp. 17-18.

Halverson, K 2010, ‘China’s WTO Accession: Economic, Legal, and Political Implications,’ Boston College International and Comparative Law Review, vol. 27, no. 2, pp. 91-105.

Harland, C, Knight, L, Lamming, R & Walker, H 2005, ‘Outsourcing: assessing the risks and benefits for organisations, sectors and nations’, International Journal of Operations & Production Management, vol. 25, no. 9, pp. 831-850.

Harriott, J, Hatfield, G & Walker, M 2009, ‘The Effect of the US-Canada Free Trade Agreement on the US Banking Market’, Journal of Multinational Financial Management, vol. 7, no. 5, pp. 145-57.

Heshmati, A 2012, ‘International impacts on economic growth in China’, Forum for Social Economics, vol. 30, no.21, pp. 25-50.

Krugman, P & Obstfeld, M 2006, International Economics, Pearson Education, Boston, MA.

Quélin, B & Duhamel, F 2003, ‘Bringing Together Strategic Outsourcing and Corporate Strategy: Outsourcing Motives and Risks’, European Management Journal, vol. 21, no. 5, pp. 647-661.

Starmass International 2013, China’s Impact On Global Market. Web.

Thach, M 2012, Financial Crisis 2009: A chance to integrate China into the global economy?, The Henry Jackson Society, New York.

United Nations 2013, World Economic Situation and Prospects. Web.