Recommendation(s)

- Pour additional resources into organizational support of women affected by social and cultural factors that contribute to domestic and intimate partner violence in Brazil.

- Provide medical and behavioral health services to women currently experiencing intimate partner violence in Brazil.

- Develop a program in partnership with local organizations to deliver health education and counseling to women affected by intimate partner violence, focusing on low-income and financially dependent individuals.

Purpose of the Submission (Background)

Intimate partner violence is a significant problem in Brazil, and the situation continues to evolve due to a variety of factors. Between 2011 and 2017, almost half a million domestic and intimate partner violence cases were reported by women living in Brazil (Mascarenhas et al., 2020). Among them, more than half were perpetrated by a male intimate partner (Mascarenhas et al., 2020; Vasconcelos et al., 2021). The abuse was mainly physical and intimate, although some also experienced mental and financial abuse as well (Mascarenhas et al., 2020; UN Women, 2022). During the COVID-19 lockdown, the incidence of intimate partner violence increased, and more women reported a higher rate of severe physical injuries (Agüero, 2021; Barbara et al., 2020; Gosangi et al., 2021). The rates demonstrate the urgent need to address the issue of domestic violence among women in Brazil.

The statistics show that the number and severity of cases have increased in the recent years, suggesting more risks for women who are financially dependent on their partners. Bhona et al. (2019) and other researchers investigate the connections between women’s social and economic status and their vulnerability to violence. It is established that intimate partner violence affects women in low-income households (Bhona et al., 2019; Coll et al., 2020; Goodmark, 2018; Kwaramba et al., 2019). Moreover, women with additional mental and physical health issues are also exposed to more violence (Bhona et al., 2019; Coll et al., 2020). In contrast, higher education, better employment, and financial independence can serve as a foundation for better partner choice and increased protection from repeated abuse (Bhona et al., 2019; Pereira & Gaspar, 2021; Perova et al., 2021). Thus, the most vulnerable part of the population is women who are at risk of financial instability if they separate from their abusive partners.

The outcomes of intimate partner violence are also long-lasting for most women. Lutgendorf (2019) reports high risks for physical, mental, and reproductive health among women exposed to abuse. During pregnancy, women can encounter various disorders, miscarriages, and psychological distress (Puccia et al., 2018). They can also develop chronic conditions, infections, and physical injuries that require medical assistance (Alhalal et al., 2018; Buffarini et al., 2021; Lutgendorf. 2019; Silva et al., 2019). In 2020, the problem of deep injuries became especially notable, as women reported more high-risk abuse (Agüero, 2021; Barbara et al., 2020; Gosangi et al., 2021). Thus, the problem of intimate partner violence is a health crisis that exposes women to both short- and long-term consequences for their mental and physical health.

Proposal

The target population for this intervention is women who currently experience or have experienced intimate partner violence and have low income or are financially dependent on their abusive partner. Furthermore, the scope of the policy is limited to Brazil for ease of implementation in one geographic region and the significant number of cases in the country (Bott et al., 2019; Brazil Institute & Waters, 2021). The initiative’s limitation to low-income individuals is necessary to focus on women who do not have the opportunity to ask for medical and psychological help from other institutions. These women are exposed to a higher risk of repeat abuse and long-term consequences to their physical and mental health (Baragatti et al., 2018; Reynolds, 2022). Therefore, it is vital to limit the scope of delivering care to women at the highest risk of further negative health impacts.

Thus, the first inclusion criterion is the female gender, including transgender women. Furthermore, incidences of intimate partner violence, low-income status, or financial dependence on one’s partner are considered. Finally, medical assistance is provided based on the woman’s specific needs and wishes, as well as the availability of the needed healthcare professional. Women can be in different relationship statuses – married and unmarried women are treated equally, and pregnant women are also accepted and provided advice on reproductive health if required.

The policy involves medical services and education for women exposed to intimate partner violence. The initiative involves two major activities – the first one is the provision of free medical services to women who are unable to access other services due to their difficult financial situation. As noted above, women from low-income households are at a higher risk of intimate partner violence (Evans et al., 2021). Moreover, financial difficulties are a strong factor in women not asking for help or trying to leave the abusive situation (Wood et al., 2021). Thus, this initiative aims to relieve some economic constraints on women and provide them with urgent or repeated medical assistance. Services may include urgent care, injury treatment, physical assessment and diagnosis, medication provision, and counseling.

The second segment of the project is education for women that focuses on increasing their financial independence and providing resources for continuing studies. The organization shares information about affordable initiatives at the nearest locations and connects women with other facilities that provide courses. This part of the project aims to help women leave their abusive situations and learn about their opportunities to decrease the risks of repeat violence. According to Weitzman (2018), educational interventions are effective in giving women more choices, increasing their financial stability, and helping them leave abusive partners. Thus, the goal of this activity is directed at long-term changes that address future statistics of intimate partner violence.

The proposed policy will take place at selected medical facilities and centers for women experiencing abuse. For example, one may partner with organizations such as Casa da Mulher Brasileira to connect women with medical and educational services (Johnson, 2020). Due to the two-fold structure of the proposed policy, its services must be available to women in healthcare organizations and facilities that offer urgent protection. Involving other organizations in protecting women from repeat offenses is the best strategy to deliver the necessary care and education.

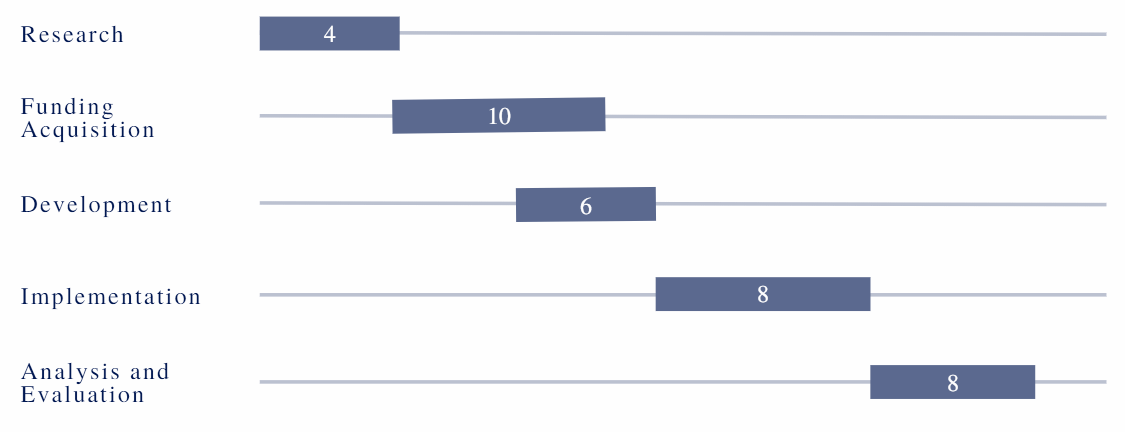

The program is expected to be provided in the span of 25 weeks. The timeline includes the periods needed for research, funding acquisition, preparation, implementation, and evaluation. During the first four weeks, the project team will research the major problems and statistics related to medical and psychological issues women face in cases of intimate partner violence. Moreover, the research will contain the examination of the most suitable locations for the program. The next ten weeks will be devoted to funding acquisition to support the program. At the same time, the starting steps for developing project roles and activities will be taken. In the remaining eleven weeks, the project will be developed, implemented, and evaluated. The Gantt Chart with the approximate schedule is presented in Attachment 1.

The project cannot be assessed using a control group, as it would require some women to stay without medical assistance in a difficult situation. Therefore, it will be evaluated by recording the number of women helped and the number of doctor appointments made for individuals involved in the project. Moreover, the number of women who complete learning courses will be included to show the outcomes and the impact of the intervention. It is possible to create long-term impact evaluations by looking at the changes in employment statistics in the chosen region as well as the rates of intimate partner violence and access to medical care. Finally, women’s well-being will be assessed using questionnaires and interviews to see whether they find this program effective in dealing with the consequences and risks of intimate partner violence.

Consultation

To develop and implement the project, one needs sufficient assistance from government and private organizations. First, external stakeholders will be addressed, as their assistance can strengthen contacts and share the information with women potentially in need of support. Moreover, some private and nonprofit organizations may lend their finances, property, specialists, and other resources to support the initiative. Next, government agencies will be covered, as their financial and legal help is vital for broadening the program’s reach.

External stakeholders

The first external stakeholder is nonprofit healthcare associations, organizations, and individuals that can provide medical and psychological help. These entities are crucial for building the program and finding professionals who can help women. For example, nonprofit organizations that can provide doctors and therapists to women or organizations that can donate supplies for healthcare procedures. These donations can significantly reduce the needed budget and supply the chosen locations with equipment.

The second external stakeholder is centers such as Casa da Mulher Brasileira which may provide a suitable location for women to get medical help and education (Johnson, 2020). Without a location where women can feel safe, the program cannot exist. Furthermore, such buildings have to be located in the selected area and have rooms suitable for delivering medical help. Classrooms or rooms with chairs and tables can be used for studying and talking to women who want to find additional resources and classes.

Government agencies

The main government agency that may be asked for assistance is the Ministry of Health. The Ministry of Health is responsible for promoting preventive care and supporting new initiatives for improving Brazilians’ well-being (Standards Portal, 2022). Therefore, it is assumed that the government agency can review the suggested program and allocate funding for its implementation. The presented program aligns with the goals of the Ministry of Health because it promotes health information and introduces a policy change to support a vulnerable population.

Risks and mitigation

One of the risks for this project is the continuous danger of COVID-19 infection in public spaces. Although the COVID-19 rates have subsided, the program’s locations will take precautions by instructing all personnel to wear masks and follow standard hygiene and disinfection procedures. The women will be supplied with masks and disinfectants to lower the risk of infection. Another risk is the privacy of women who ask for assistance, as intimate partner violence victims may still be in an unhealthy relationship. To mitigate this risk, the records of each visiting individual will be coded and stored in a safe location, and their private information will be removed from all statistics.

Financial requirements

The funding for the program is expected to come from the selected government agency, nonprofit organizations, and donations. The program’s positive outcomes are supported by research, and the potential benefit of this project is substantial. These arguments will be presented to the potential stakeholders to increase the feasibility of fully funding the program and the necessary resources. The program is sustainable in the long term, as it is expected to increase the labor force in Brazil and provide more women with an opportunity to leave abusive relationships and become financially independent.

Outcomes

Data recorded during the project will be compiled and evaluated in the form of a report. The report will contain a full description of the problem based on the research performed during the initial investigation. Then, the project’s description will be provided, listing all types of support and education provided to women. The document will outline the rates of women who received help and their feedback on the program. The evaluation of the project will be included to show whether the program changed the circumstances of women in Brazil.

It is expected that the presented numbers will show the positive impact of affordable medical assistance and teaching for women who suffered intimate partner violence. As a result, the program may grow into a larger system of support for women in Brazil, decreasing the negative consequences of abuse and lowering the rate of repeat violence. Although the scope of the proposed project is small, its conclusions will focus on future implementations and avenues for additional research.

References

Agüero, J. M. (2021). COVID-19 and the rise of intimate partner violence.World development, 137, 105217. Web.

Alhalal, E., Ford-Gilboe, M., Wong, C., & AlBuhairan, F. (2018). Factors mediating the impacts of child abuse and intimate partner violence on chronic pain: A cross-sectional study.BMC Women’s Health, 18(1). Web.

Baragatti, D. Y., Carlos, D. M., Leitão, M. N. D. C., Ferriani, M. D. G. C., & Silva, E. M. (2018). Critical path of women in situations of intimate partner violence.Revista Latino-Americana de Enfermagem, 26. Web.

Barbara, G., Facchin, F., Micci, L., Rendiniello, M., Giulini, P., Cattaneo, C., Vercellini, P., & Kustermann, A. (2020). COVID-19, lockdown, and intimate partner violence: some data from an Italian service and suggestions for future approaches. Journal of Women’s Health, 29(10), 1239-1242.

Bhona, F. M. D. C., Gebara, C. F. D. P., Noto, A. R., Vieira, M. D. T., & Lourenço, L. M. (2019). Socioeconomic factors and intimate partner violence: A household survey. Trends in Psychology, 27, 205-218.

Bott, S., Guedes, A., Ruiz-Celis, A. P., & Mendoza, J. A. (2019). Intimate partner violence in the Americas: A systematic review and reanalysis of national prevalence estimates. Revista Panamericana de Salud Publica, 43, e26. Web.

Brazil Institute & Waters, J. (2021). Fighting gender-based violence in Brazil. Wilson Center. Web.

Buffarini, R., Coll, C. V., Moffitt, T., da Silveira, M. F., Barros, F., & Murray, J. (2021). Intimate partner violence against women and child maltreatment in a Brazilian birth cohort study: Co-occurrence and shared risk factors. BMJ Global Health, 6(4), e004306. Web.

Coll, C. V., Ewerling, F., García-Moreno, C., Hellwig, F., & Barros, A. J. (2020). Intimate partner violence in 46 low-income and middle-income countries: An appraisal of the most vulnerable groups of women using national health surveys. BMJ Global Health, 5(1), e002208.

Evans, D. P., Shojaie, D. Z., Sahay, K. M., DeSousa, N. W., Hall, C. D., & Vertamatti, M. A. (2021). Intimate partner violence: Barriers to action and opportunities for intervention among health care providers in São Paulo, Brazil. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(21-22), 9941-9955.

Goodmark, L. (2018). Decriminalizing domestic violence: A balanced policy approach to intimate partner violence. Univ of California Press.

Gosangi, B., Park, H., Thomas, R., Gujrathi, R., Bay, C. P., Raja, A. S.,… & Khurana, B. (2021). Exacerbation of physical intimate partner violence during COVID-19 pandemic. Radiology, 298(1), E38-E45.

Johnson, S. (2020). ‘We wrap services around women’: Brazil’s innovative domestic violence centre. The Guardian. Web.

Kwaramba, T., Ye, J. J., Elahi, C., Lunyera, J., Oliveira, A. C., Sanches Calvo, P. R., de Andrade, L., Vissoci, J., & Staton, C. A. (2019). Lifetime prevalence of intimate partner violence against women in an urban Brazilian city: A cross-sectional survey.PLoS One, 14(11), e0224204. Web.

Lutgendorf, M. A. (2019). Intimate partner violence and women’s health.Obstetrics & Gynecology, 134(3), 470-480. Web.

Mascarenhas, M. D. M., Tomaz, G. R., Meneses, G. M. S. D., Rodrigues, M. T. P., Pereira, V. O. D. M., & Corassa, R. B. (2020). Analysis of notifications of intimate partner violence against women, Brazil, 2011-2017. Revista Brasileira de Epidemiologia, 23.

Pereira, M. U. L., & Gaspar, R. S. (2021). Socioeconomic factors associated with reports of domestic violence in large Brazilian cities. Frontiers in Public Health, 9, 623185.

Perova, E., Reynolds, S., & Schmutte, I. (2021). Does the gender wage gap influence intimate partner violence in Brazil? Evidence from administrative health data. World Bank Group. Web.

Puccia, M. I. R., Mamede, M. V., & de Souza, L. (2018). Intimate partner violence and severe maternal morbidity among pregnant and postpartum women in São Paulo, Brazil.Journal of Human Growth and Development, 28(2), 165-174. Web.

Reynolds, S. A. (2022). Do health sector measures of violence against women at different levels of severity correlate? Evidence from Brazil. BMC Women’s Health, 22(1).

Silva, E. P., Ludermir, A. B., de Carvalho Lima, M., Eickmann, S. H., & Emond, A. (2019). Mental health of children exposed to intimate partner violence against their mother: A longitudinal study from Brazil. Child Abuse & Neglect, 92, 1-11.

Standards Portal. (2022). Brazilian government entities. Web.

UN Women. (2022). Brazil: Prevalence data on different forms of violence against women. Web.

Vasconcelos, N. M. D., Andrade, F. M. D. D., Gomes, C. S., Pinto, I. V., & Malta, D. C. (2021). Prevalence and factors associated with intimate partner violence against adult women in Brazil: National Survey of Health, 2019. Revista Brasileira de Epidemiologia, 24, e210020.

Weitzman, A. (2018). Does increasing women’s education reduce their risk of intimate partner violence? Evidence from an education policy reform. Criminology, 56(3), 574-607.

Wood, S. N., Glass, N., & Decker, M. R. (2021). An integrative review of safety strategies for women experiencing intimate partner violence in low-and middle-income countries. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 22(1), 68-82.

Attachments