Introduction

Islamic bank is a term used to define financial institutions that are governed by tenets of Islamic laws and regulations. Islamic banking system is quite different from financial practices of mainstream banks in more than one way. Basically Islamic banking is similar to mainstream banking in practice and in most other routine functions, however it differs in areas that pertains to interest, profit and loss sharing which are the characteristic features of the Islamic banking system that sets it apart (El-Gamal). A working definition given by Hassan and Lewis in the Handbook of Islamic Banking describes Islamic banks as financial institutions that “provide a variety of religiously acceptable financial services to the Muslim communities” and thereby serve an important socio-economic role (2007).

The Islamic laws and code of practice that governs the profit and loss sharing (PL S) concept are encompassed in the Islamic principles that are referred as Fiqh al-Muamalt. Because a major characteristic feature of Islamic banks pertains to it Profit and Loss sharing principle which is what sets it apart from mainstream banks let us briefly review what this concept of PLS entails. The PLS concept that is a common feature of all IFIs is contained in the bank’s lending principles. The Islamic banks approach to lending is very unconventional in that the bank does not give out the loan to a borrower per se, but instead acquires the asset on behalf of the borrower who is then supposed to institute repayment to the banks in installments. This for instance is usually referred as Murabaha when the loan is made towards mortgage (El-Gamal). Another unique feature of Islamic banking pertains to it approach on lending; it does not set out uniform interest rates for all companies but rather customize interest rates to match the company financial performance. This means companies with high profit returns are charged more, a concept defined by the floating rate interest on loan system (El-Gamal). This core values and features of Islamic banking are the backdrop in which we are going to discuss the various securitization financial products that we have so far outlined above. But first let us briefly outline what securitization transaction entails in general.

Securitization refers to a process that involves conversion of financial assets into securities that are easy to manage; it involves transformation of existing financial assets through pooling and repackaging them to a new form of securities. In a research paper written by Kettering, securitization is described as “a transaction that, in the first place, involves the issuance to financiers of debt instruments that are backed by a designated pool of assets” (Kettering). These assets securities are gradually transformed and positioned to what the author refers as “bankruptcy isolation of the securitized assets” (Kettering). In the current banking industry the importance of securitization are two folds; one, it facilitates transformation of financial assets to more liquid assets that are more easy to trade on than would otherwise be the case when securitization process has not taken place (Kettering). Secondly, because financial assets have been injected with liquidity through securitization, this process thereby facilitates trade of financial assets through sukuk at both primary and secondary markets undertaken at a premium (Kettering).

Indeed, it is for these two main reasons that the processes of securitization transactions were first invented back in 1970s; during this early period securitization transactions were predominantly used in transformation of asset pools that were mainly compromised of mortgages, referred as murabaha (Alkhan). Since the invention of securitization during this time when asset-backed transactions became the norm, various research studies had placed the financial value of securitized assets to surpass the US$ 4 trillion mark as of 2003 for mortgages only (FederalReserve.org). In Islamic banking securitization of assets is even a more recent occurrence that has taken shape over the few last decades agitated by the securitization trend that has been taking place in the mainstream financial institutions.

In the following section let us briefly review the major characteristics of Islamic banks and thereby lay the foundation in which the rest of the discussion on this paper will be based. This is necessary because of the way that IFIs are structured which is very different from mainstream banks; thus in order to understand the Islamic banking concept it is imperative we have a background insight on how Islamic banks are structured and how they functions.

An Overview of Islamic Banks and Islamic Principles

The functions of Islamic banks goes beyond the mainstream banking functions in that an Islamic bank doubles up as a trader, investor and a consultant with mandates that has traditional been profit maximization just like any other financial institution (Hassan). As such the distinct nature of Islamic banking has advantages that arise as a result of its financial transactions and which is also its disadvantages. The major advantage of Islamic banking is confined to the banks concept of Profit and Loss Sharing (PLS), in this arrangement the banks depositors are strictly speaking not creditors to the bank, but rather very similar to shareholders who stand to absorb a certain percentage of the banks profit and losses as outlined in the banking contract (Hassan). The implication of this arrangement is that Islamic banks are more insulated from financial losses that emanate from depositors capital than their conventional counterparts.

The disadvantages that are inherent in the Islamic banking system are proportional to the advantages that the bank enjoys in respect to the depositors funds. The same contract between the bank and the depositor that provides for risk sharing also contains components that protect the depositor from non-procedural banking operations that can results in losses. In such a case the bank is obligated to compensate the depositor with full deposited funds or face legal actions, in what is usually referred as Fiduciary Risk. Closely associated with this type of risk is Displaced Commercial Risk, a form of risk that Islamic bank are exposed to whenever they move to top up the depositors “perceived profit sharing”, to be at par with interests that conventional banks are offering at the time (Hassan 2004).

This is despite the fact that the bank profits might not be sufficient to provide for such percentage but which they are compelled to pay or face depositor’s financial sabotage. In order to do this the bank has to re-allocate the bank shareholders funds by toppling their profit sharing obligations to cover the shortfall. Other areas that the bank faces risks are in areas of collateral, market risk, credit risk, and bank equity since Islamic bank significantly differ with universal banks in terms of funds mobilization. Indeed the current way in which Islamic banks calculate Capital Adequacy Ratio (CAR) is an indicator of their unique banking system (Basel.org). Because of Ijarah or Murabaha the bank has adopted a form of a matrix format to calculate CAR at any given time during the various stages where a borrower is servicing the loan.

More so the bank risk changes from price risk to credit risk, a feature which must be incorporated in CAR calculations (Hassan). The implications of CAR in Islamic banks and how it generally impacts on various securitizations transactions in IFIs would become apparent as we continue with our discussion in later sections. In fact what we realize is that many financial products of Islamic banks including the core financial principles of Islam such as profit-loss sharing and sukuk have not been provided at all in both Basel accords. This is a major oversight when you consider that Basel is the universal financial body with mandate to provide financial guidelines to all financial institutions globally.

An Islamic concept that will be at the centre of our discussion throughout this paper is referred as sukuk; sukuk is the equivalent of what the universal banks refer as bonds, but which does not provide for fixed interest rates or indeed any form of interest based returns on investments at all (Hassan). As a result Basel I capital adequacy guidelines for instance are limited insofar as application of these guideline in calculation of CAR is concerned where sukuk exist; nevertheless, the Accounting and Auditing Organization for Islamic Financial Institutions (AAOIFI) provides a workable framework (Timberg). Islamic banks are therefore able to calculate most forms of credit risks using standard approach method, but there are other cases where credit risk calculations do not apply such as in Musharaka and Mudaraba.

In such cases the banks normally applies specialized lending guidelines that are outlined in Basel II such as the “supervisory slotting method” or the “equity position risk in banking book method” (Timberg). Despite this, Islamic banks continue to face challenges and unique risks as well such as the Sharia Compliance Risk (Timberg). This is a form of risk faced only by Islamic banks which include financial losses encountered due to financial transactions that arise from non-recognition of specific sources of incomes or losses associated with compliance to Islamic banking regulations. In the following section we shall discuss in summary the major Islamic principles that govern IFIs financial regulations.

Basic Islamic Principles

Because the securitization process in Islamic banks is governed by shariah laws as well as the Islamic financial principles, let us briefly review the major Islamic principles that are applied in all forms of business transactions. There are just a handful of fundamental Islamic laws that are integral in almost all forms of business deals, these are; ban on riba which is interest, ban on gharar-maisir, the shariah PLS concept, law on ethical forms of investments and asset backing (Ayub). Perhaps the most fundamental of these laws as we shall see throughout this paper is the ban on riba, in fact it is the law that is always kept in mind when designing all forms of securitization products because interest-based transactions are completely not permissible under the Islamic laws. It is also the law that is inferred the most times in the Quran which would mean its importance is greatly emphasized; in a nut shell the shariah law on riba states that “Allah hath permitted trade and forbidden usury” (Gurulkan).

The Islamic law that prohibits gharar-maisir which mean business transactions that are undertaken on “excessive uncertainty” is seen to imply from an Islam perspective not to engage in gambling-like business activities (Gurulkan). This Islamic law effectively prohibits trade practices that are described in conventional banking as speculative trading whose level of risk are as high as the expected return on investment which would be in reference to transactions such as gambling, betting, lotteries and such similar games. PLS sharing concept is a fundamental law in Islam just as the law on prohibition of riba; every aspect of trade under taken in compliant of Islamic law must be based on equal sharing of profit and loss that is proportion to their investment. This in practice implies that the interest-based trading which is prohibited in Islam would have no room in trade transactions.

The other Islamic law requires that all form of investment ventures be undertaken for a good cause that enhances the welfare of the community (Gurulkan). It is for this reason that Islamic transactions are very particular at establishing the legitimacy of asset pools which is one of the steps that must be undertaken in securitization of assets as we shall later see in this paper. Finally, all forms of trade must be asset-backed; this implies that money must be channeled through an asset in order to generate the required profit which will be shared in accordance with PLS concept. Without asset-backed transactions shariah law prohibits any form of profit to be gained from such a transaction. Now, with this in mind let us undertake a critical analysis of what securitization concept entails from an Islamic banking perspective before we get to discuss the individual aspect of various securitization products that exist in the IFIs.

The Securitization Concept

The fundamental purpose that securitization serves for both the conventional banks and Islamic banks are similar in that both forms of these two financial institutions relies on securitization of assets as a gateway of obtaining additional funds while at the same time securing the collateral assets that they have so far accumulated.

This is because the concept of securitization allows financial institutions to trade on “income-earning asset” as securities and thereby obtain required liquid capital that was previously tied by these types of financial assets (Gurulkan). Perhaps the best simplified definition of securitization is given by Gurulkan who defines it as “the process of making a loan or mortgage into a tradable security by issuing a bill of exchange or other negotiable paper in place of it”. Any securitization process involves about a total of four various related components; sale of assets, presence of cash flow that is generated by the liquidated asset, enactment of a separate entity referred as SPV which manages the cash flow and the assets and finally, the investors whose capital are used to liquidate the capital and the ones benefiting from the proceeds of the asset (Gurulkan).

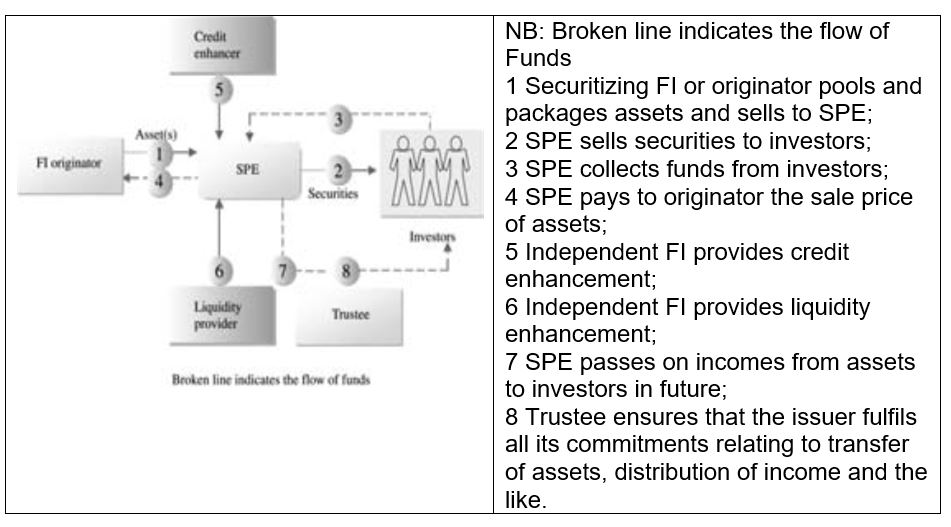

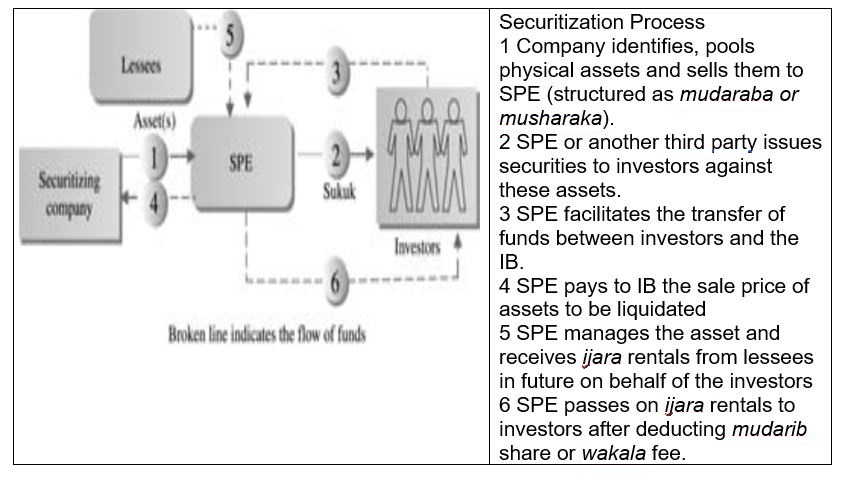

In Islamic banking the importance of liquidity which is central to the process of securitization is encompassed by an Islamic concept referred as al-suyulah. The integral elements of securitization process are comprised of several stakeholders whom include the following. The originator which is the financial institution responsible for pooling the assets, a Special Purpose Entity (SPE) who acts as the issuer, trustee who oversees and manages the asset and credit guarantors (Obaidulah). A diagrammatic representation of the major processes and players that are involved in the process of securitization is depicted below in a diagram adopted from the Handbook of Islamic Banking which articulately captures this relationship very accurately.

In IFIs the importance of asset securitization is well elaborated to be crucial by various research studies because of the economic benefits that it provides to the institutions as well as other stakeholders in what is referred as maslaha. However, as we discuss more this concept of securitization as it applies to Islamic banking, it is going to become apparent that the structures and financial regulations of Islamic banks which must be in accordance with shari’a laws means that IFIs are constrained from benefiting optimally from securitization. Foremost, the fact that IFIs has only evolved recently over the last three decades or so, means that they have been late in adopting this concept of securitization from mainstream banks from where it was originally invented and therefore not yet fully refined (Shenker and Colletta). Secondly, Islamic banks has a challenge of ensuring that securitization transactions are compatible with the Islamic shari’a laws and tenets; while the essence concept of securitization is allowed under shar’a law, there are nevertheless other aspects in securitization that could be contravening some of the Islamic shari’a principles such as gharar and riba as we shall see at a later section (Shenker and Colletta).

Another challenge that faces Islamic banks when it comes to transactions involving securitization is conforming to the shari’a law of riba; because sharia law prohibit IFIs from transacting in types of asset which provides for interest, Islamic banks must therefore find a way to circumvent this problem. A research paper by Zaher and Kabir states that “the Islamic community has rationalized the elimination of riba interest based upon values of justice, efficiency, stability and growth” to be the core values that are integrated in all forms of IFIs (Zaher and Kabir). Four, the sharia law prohibits transfer of financial cash or debt between parties at a premium since this will constitute interest which is riba. Thus to determine which type of financial assets qualifies to be transferred at negotiated price and which must be transacted at par, the rule of thumb is to ensure that physical assets and financial claims are apportioned in such a way where the physical assets accounts for majority of shares above the 50% mark, otherwise any resulting securitization transaction must be transferred at par (Zaher and Kabir).

Five, because of the sharia laws constraints in which Islamic banks operate under, the implication is that securitization process in IFIs is strictly defined in order to avoid contravening the Islamic financial principles thereby limiting the rate at which securitization occurs in IFIs as well as complicating the whole process. Having discussed in general the special challenges that securitization process presents to IFIs sector, let us now take a closer look at a model process of securitization that conforms to Islamic laws as they currently exists.

Securitization in IFIs

The various securitization transactions that exist in Islamic banks were first made popular by introduction of Islamic Private Debt Securities (PDS) that first took root in Malaysia. It was during this time that the most common Islamic securitization transaction referred as murabaha become very widespread (Shenker and Colletta). As Islamic banks continued evolving and expanding throughout 1990s and 2000s, more securitization transactions were invented and currently includes a range of several such transactions which we shall discuss in more detail throughout this paper.

In Islamic banks securitization of assets is undertaken in similar process that exists in mainstream banks and requires creation of SPV which will have the mandate to issue the sukuk bonds to the investors. However, under Islamic laws the securitization process must be structured in order to adhere to shariah laws that govern the financial principles of IBs; for instance it is paramount that the asset pool of securitized assets not be from any proceeds of haram earnings (Obaidulah). In addition, shariah laws require that the investor be given a certain shares of ownership in any securitization process which is usually achieved by transfer of certain ownership rights. Finally, the basis on which investment is made under Islamic laws must be anchored on partnership that advocates PLS concept rather than interest-based financing (Obaidulah).

An integral component for all these securitization process involve a common element that is referred as mudaraba but which is referred as SPE in the mainstream banking. In Islamic banking, mudaraba refers to the investors who are willing to obtain the financial assets in exchange of liquid capital while mudarib refers to the Company that is fronting the securitization of the assets. In Islamic banks, the natures of securitization that the bank transacts in are largely trade-based, termed as murabaha or leasing based, ijara (Obaidulah). Ideally, the process of securitization in Islamic banks involves the original transaction of the financial asset to the acquiring bank which would later become the originator under the frameworks of murabaha when the transaction is trade-based, or bai-bi thamin ajil when it is lease-based (Obaidulah).

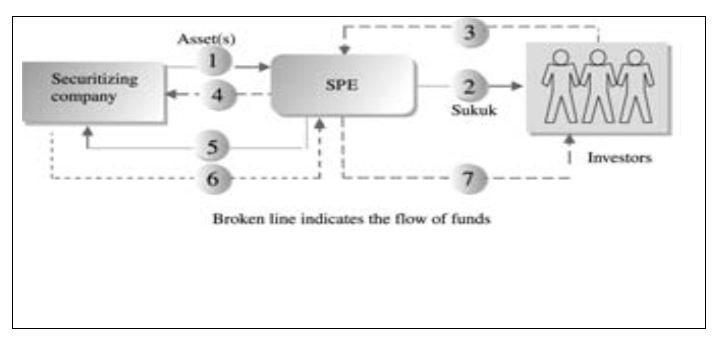

Because, the acquisition of such assets are undertaken out of debt, the Islamic shariah laws prohibits riba in their resulting transactions which means that they can only be transferred to a third party at par. The securitization process requires creation of SPE just as in conventional banking industry which has the mandate to manage the pool of assets. Because, acquisition of these financial assets by musharaka, whom represent the SPE in IBs does not change the fact that they are assets advanced on debt, further transfer of these now liquidated assets can still be only at par. This means a secondary market in the securitization chain when it comes to Islamic banks would not exist. A securitization process that is unique to Islamic financial institutions is depicted in the following diagram which articulately presents how the same process in mainstream banks has been customized to reflect an Islamic securitization process that is shariah compliant.

What is different in this process is that under Islamic laws the securitization process must also involve two other processes; one, a verification exercise that assess the compliance of asset pool with shariah laws and two, the business deal structure which involve issues of credit enhancement and so on (Gurulkan).

To understand how the various securitization transactions has gradually evolved in the Islamic sector, one would have to understand how IFIs utilizes depositors funds; to this regard there are three forms of applications in general that Islamic banks can commit their funds. One of the most popular applications among these three is a form of contract which are referred as exchange or fixed income instruments (Kayed and Kabir). In this category we have four major contracts that the banks have invented; murabaha, ijara, salam and Istisna (Kayed and Kabir).

The major advantages of this category of fixed income contracts are two; one, because they provide the bank with minimal risk exposure, and two because they are relatively easy to implement. As we get to discuss these various securitization contracts in detail we shall see how this is so. The second category in which the IFIs can commit their funds is referred as Profit Sharing Equity instruments which are mainly two; mudaraba and musharaka (Kayed and Kabir). Finally, we have a third category that mainly involves commitment of funds in service products which occurs in form of agency services and currency services among others.

Like all forms of securitization transactions it is imperative that the securitization process under the Islamic tenets certify these three conditions; one, there must be transfer of asset from the seller who is the originator upon exchange of pre-agreed financial amount, this is referred as confirmation of a legal isolation that must be “presumptively beyond the reach of the transferor and its creditors” (Gurulkan). Two, certain rights must be realized by the new owners upon acquisition of the asset which generally involves right to pledge the particular asset for whatever reasons that the owners desire (Kayed and Kabir). Finally, the securitization process must be structured in a way that would bar the seller from being able to reacquire the asset back (Kayed and Kabir). In the following section we now take a critical analysis on each of the various Islamic contracts that are commonly found in IFIs.

Special Purpose Vehicle-Silent Partnership

Traditionally, Islamic banks are structured in a way that provides for what can be described as “two-tier silent partnership”; this means that at one level the depositors of the bank who wish to obtain return on their deposit would be given a stake in the bank’s portfolio rather than obtain loan, this is what is referred as silent-partnership investments (El-Gamel). On another level the bank would invest some of this deposit on other external silent partnership ventures that are essentially PLS in which they would still allow the depositors to claim a certain percentage. Thus, in silent-partnership it becomes necessary to securitize assets which would mean creation of an SPV entity.

Because the originator of the asset who intends to liquidate the asset through securitization process needs to guarantee the investors on the availability of the asset, it becomes necessary to form a separate entity that would provide security to investors who intends to contribute funds towards such a venture. This is where the formation of SPV comes in; SPV is thus formed for a specific financial transaction and serves the purposes of “housing the asset” so to speak during the securitization period and also to guarantee security on investor’s money (Gurulkan). This way the investors contribution are compartmentalized from the originator asset pool and the probability of various forms of risks are drastically reduced which assures the investors.

Thus, Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV) functions as medium that facilitates transfer of funds between the investors and the assets that are being liquidated. In Islamic banking, the functions of SPV can also be taken up by Special Purpose Mudaraba (SPM) which is the equivalent of SPV entity in securitization process of mainstream banks (Ayub). The importance of SPV/SPM in the securitization process serves two important functions which we shall elaborate more in the following sections; one, it acts as an agent to the investors with the express mandate of managing the liquidated assets and thereby secures return of investors’ capital (Ayub).

Two, the SPV serves another important function that involves issuance of investment certificates that are inform of securities thereby facilitating primary and sometimes secondary trading in these securities and thereby promote a robust market environment (Ayub).

Thus, SPV functions as a separate entity from two of the major stakeholders in this process of securitization which normally include the Islamic bank and the investor. For these reasons, it is best for SPV to be formed as a body with separate legal entity but which is often described as also being “substantive non-entity” (Gurulkan). The implications is that it becomes what is referred in financial circles as bankruptcy-remote entity primarily because it is not even physically there, requires no license to operate or even employees which would mean it has no expenses that might result in it bankruptcy, and this is for good reasons if you were to imagine the implications.

In every Islamic country where SPV entities need to be enacted the specific working framework that SPVs require to operate under tends to change based on the financial policies as well as interpretation of the shariah laws in that country. But as a matter of fact, SPV mandate in general involve the two major functions that we have outlined above; also notable to mention is that SPV only take over management of asset only after the asset has been liquidated by the investor’s fund. Also in general, SPVs usually has only two major structures of payment which are described as “pass-through structure” or “pay-through structure” (Obaidulah). Pass-through structure is when the SPV collects and passes in full the all earnings emanating from liquidated financial assets directly to the investors.

Pay-through on the other hand is when the SPV apportions the generated cash flow from the pool of asset towards servicing the bond and at the same time allows collateralization of the asset pool (Obaidulah).

In summary therefore, the importance of SPV in the process of securitization serves three important roles; one, it isolates the targeted assets of liquidation from the originator, two, it compartmentalize the credit risk that could result from securitization process by segmenting the process and finally it structures the generated cash flow by transforming them from financial assets to tradable products.

Securitization of Murabaha

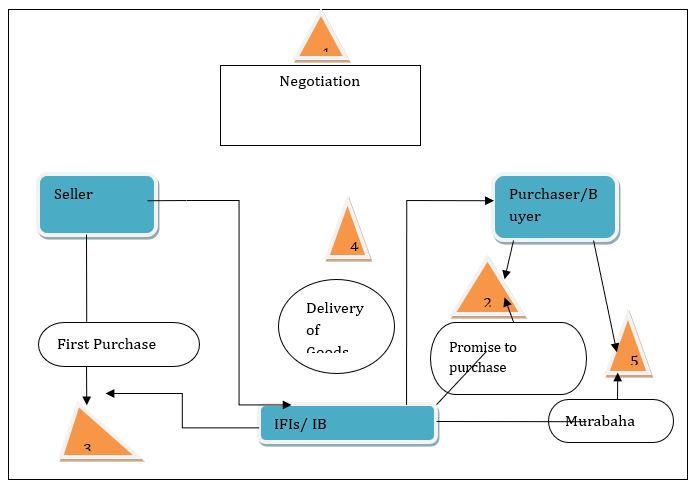

In Islamic banking murabaha entails what can be termed as Cost-Plus Sale contract; in its simplest terms, murabaha entails a securitization process that is only structured to generate a certain profit to the investors. Under shariah laws, murabaha entails a sale contract that can take either of these two forms; installment credit made to the bank or form of deferred payment sale (Obaidulah). Thus in murabaha, either way the buyer has to institute payments that are made up of the principal amount in addition to the pre-agreed profit. A murabaha contract may involve other parties rather than the buyer and the seller which is the bank; when a third party is involved in the transaction to function as an intermediary between the two principle parties, that party becomes an agent usually referred as wakil. Thus, the simplest form of a murabaha contract involves a buyer and the bank, which would normally appoint an agent whereby both parties agree on the mark-up price of the sale that should be paid at the end of the transaction period.

A typical murabaha contract and the transaction process that result from these agreement is well elaborated on this simplified chart which clearly depicts IFIs as the financier that secures the goods on behalf of the buyer.

This is the ideal form of murabaha contract that is permissible by Islamic banking since it is a securitization process that conforms to the Islamic shariah laws, notably because the same goods are not sold again to the seller at an interest as is the case in another variant of murabaha that is only found in Malaysia referred as mutabaha-BBA (bai-bi-thamin ajil) (Obaidulah). In this form of murabaha, the banks initiates sales of assets to SPE Company through the normal mudaraba contract, thereafter the bank then buys the same assets but this time with a mark-up value that would be paid on deferred basis.

This process is what is referred in Islam as bai’al-inah to mean a transaction that involves sale and buy-back which under Islamic shariah law is perceived as riba-based borrowing and therefore prohibited. This is because the point of laundering the financial asset between the bank and the customer is for purposes of creating interest on a debt-asset, which the Islamic shariah law saw as unwarranted riba. The murabaha-BBA is thus normally frown upon by many Islamic banks. Besides, the process of sale and buy-back that results from this form of securitization leads to separation of financial assets from the mode of financing which is also not allowed under the Islamic tenets. The following figure diagrammatically represents this form of BBA-murahaba securitization process that remains contentious because it essentially condones premium to be charged on sale of debt.

What is notable about this securitization transaction is that the securitizing Company that initially sells the financial assets to the SPE gets to obtain back the same assets under a new financing scheme. These results to sukuk-al-murabaha, which should ideally be freely traded with premium, were it not for the fact that in this case the securitization process of assets had allowed riba in what is actually sale of debt.

It is notable to mention that murabaha was actually invented to serve a particular purpose back in 1980 when IFIs had excessive liquidity capital in the midst of a western credit crunch which meant the western nations were desperate to obtain loans from these institutions. In order to circumvent the shariah law on riba which was very particular on disallowing riba on sale of debt or debt asset, murabaha was invented (El-Gamel)

Thus, typically securitization process of murabaha is still widespread despite its early contravention of Islamic shariah laws because it has now been structured to conform to the Islamic principles of riba. This is because over the years Islamic banks have strived to position securitization of murabaha to be compliant with shariah laws; among the various ways that murabaha has been structured include allowing trade in precious metals but which do not include gold or silver. This was following the shariah interpretation by some Muslim jurist who had ruled that trade in other commodities excluding the five commodities described in Koran was permissible to charge riba on top of the principal amount. Another form of murabaha securitization that is closely related to bai-al inah is referred as Tawarruq whereby the bank or investor makes profit through on spot transfer of goods to a customer who pays the principle amount plus interest using the seller as an agent.

Securitization of Ijarah

Ijara is a form of payment contract in Islamic laws that involve payment on usufruct, which is temporally usage of what is normally an asset. The ijara contract requires that a lessee of such an asset make payments in form of goods or services at the end of usage; throughout this process the ownership of the asset does not change hands between the lessor and lessee (Obaidulah). The ijara-based securitization transactions owes their origin from Bahrain Monetary Agency which is responsible for popularizing the ijara certificates that were aimed at generating liquidity capital of a target value exceeding $100 million with a maturity of 5 years (Obaidulah).

The payment that is made for using such a product is what is referred as rent which can either be fixed or variable; in this arrangement the bank is usually the lessor while the client is the lessee upon which the asset is entrusted to for purposes of usufruct. Normally, what therefore happens in ijara contract is that the bank obtains an asset from a manufacturer which it owns and then contracts it to the lessee at mutually agreed terms for usage; these rental payments are what constitute ijara (Obaidulah). In this process of asset rental, Islamic shariah laws permits enactment of sub-leases which can be contracted again between the main lessee and other sub-lessees whom one may desire to incorporate as long as the lessor is aware of such an arrangement.

The importance of ijara concept to the process of securitization offers more advantages over shariah law limitations that are inherent in murabaha securitization. In fact, ijara-based securitization provides more convenient way of liquidating assets where other methods of securitizations are not possible because of the Islamic principles barriers.

Because ijara-based securitization deals with securitization of physical asset, it means that a major hurdle in shariah law that prohibits riba on debt transfer does not apply in this case. What usually happens in ijara-based securitization process is that the IB institutes transfer of a physical asset to the SPE which then liaises with investors to solicit funds in exchange of transfer of the assets. The SPE manages the asset on behalf of the investors in exchange of wakala, or mudarib, whichever they agree on; the investors on the other hand having acquired the asset gets to obtain all form of risks as well as reward that would result from this acquisition in future.

Most often the reward that they would obtain from such assets would largely result from leasing the asset which the SPE would oversee on behalf of the investors. As for the risks, another stakeholder is usually assigned the task of insuring the asset to guarantee the investor capital as well as lease payment through credit enhancement; it is such guarantees that result to issuance of security by a third party as we shall shortly see. The earnings that result from the lease of the physical asset are usually shared among the investors on a pro rata basis in proportion to their capital input; the security bonds that are floated to guarantee these earnings normally by a third party who bears the responsibility of risks or by SPE investors are what is referred as sukuk-al-ijara (Obaidulah). This form of security bond can be traded at premium by the primary investors who wish to transfer their rights of income at a profit because the Islamic shariah laws do not essentially prohibit riba on transfer of physical asset that have not resulted from debt.

This is the major reason why ijara-based securitization is more suitable as a way of liquidating physical assets because it encourages secondary trading of sukuk-al-ijara bonds in the market which creates a wider market in which investors can trade in, and consequently in which the IFIs can potentially tap to obtain the necessary liquid capital. But this is only as far as sukuk-al-ijara is concerned; there is a form of ijara-based securitization that does not allow for transfer of security bonds with premium value because of the fact that the original asset was a form of a debt, this is referred as sukuk-al-murabaha (Obaidulah). The following flow chart depicts the stakeholders as well as the process that result in liquidation of physical asset in ijara-based securitization process.

Securitization of Salam

Salam is a form of Islamic contract which involves full payment on procured assets termed as “spot payment” because it is paid in full immediately after ordering the goods without necessarily having to await their delivery (Obaidulah). All forms of salam contracts can be summarized under two broad conditions; one, during the process of contracting it is not mandatory that the goods being contracted be in existence. Secondly, because the delivery of goods is delayed it means the ownership rights of goods do not immediately get transferred to the client. As we shall see later in this paper on the securitization of istisnaa, the similarity between salam contract and istisnaa is extremely close; both of these contracts for instance achieve securitization of projects that generates income prospectively.

The nature of goods that are covered in salam contracts are defined by shariah law as “assets which have commodity-like characteristics and must be fungible like base metals, eg, copper and zinc, and grain, promised for future delivery” (Gurulkan). The element of future delivery and in advance payment are unique features for salam contract; other features of salam contract require that the commodity of trade be goods that are freely exchanged of specific quality and quantity. Because the bank must be the one to undertake on spot payment of the product in a typical salaam transaction the type of risk that IBs must bear during this type of transaction is price risk which can result between the time of payment and delivery of goods.

Under the shariah laws Islamic banks or investors are allowed to make profits out of their investment under the agreement of a salam transaction; in this case what happens is that bank makes the full payment of the commodity which gets transferred to the client who will be responsible for making the full payment plus mark-up value paid after the sale of goods. Thus, the client in this arrangement becomes the trader who also doubles up as the banks agent with the mandate to redistribute the commodities on behalf of the bank to recover the principal amount as well as a certain percent on profit which has been pre-determined well in advance. The factors that are considered in determination of pricing as well as the percent of the mark-up value include; cost of labor, profit margin required, credit rating of supplier and strength of security undertaken on goods (Gurulkan).

Having discussed what the salam contract generally entails in principal, then we can see how securitization of salam can occur under the Islamic tenets of shariah laws. The most common form of securitization of salam contracts involve government entities that wish to raise funds for specific projects. What happens therefore is that a government seeks funds from the public with intention of procuring commodities that are permissible by shariah laws as far as salam contracts are concerned to be paid on spot as delivery of goods is awaited. Once the deliveries of the procured commodities are obtained the salam contract securities are sold at premium price by the government to generate the interest that the government now distributes to the investors on a pro rata basis. The excess profit that is shared among the investors is what becomes the return on investment that was initially given by the public; this promise on future earnings after trading on procured goods is what can be securitized to generate the required capital in what is referred as securitization of salam.

Whether securities that emanate from a salam contract can be transferred to secondary market by the original investors at a premium remains a contentious issue that various religious scholars have not yet arrived at an agreement. The contention emanates from the shariah law which holds that “a good cannot be sold before coming into its possession” which is the case for all forms of salam contracts and even istisnaa contracts as well (Gurulkan). The majority of Islamic community however condones secondary trade of securities from salam contract with profit mark-up in securitization of salam for two reasons; foremost because salam contracts as structured under Islamic laws must provides a form of guarantee on delivery of goods. And two, because the guarantor of public funds in this case is the government which is generally considered very stable financially and reliable.

Securitization of Musharaka

Musharaka is a form of contract financing that is under the category of Profit Sharing Equity methods which means it is basically a form of partnership that provides for profit sharing in accordance with shariah laws. Generally musharaka is very similar to mudaraba in principles; in Islamic laws musharaka is categorized into two forms; shirkat al aqd and shirkat al milk (Alkhan). Shirkat al milk refers to a form of partnership on an asset that exists between more than two parties which does not necessarily have to be defined through a form of an agreement such as a contract. A typical example of shirkat al milk musharaka is a form of financial asset that is obtained through inheritance which the shariah law prohibits from being divided among the parties. Shirkat al aqd on the other hand is partnership on asset between various parties that has been pre-agreed on various issues that pertains for instance on return on profit and so on (Alkhan). In fact it is the basis on which all musharaka contracts are done because it requires parties to such an agreement to freely engage as well as to negotiate on the specifics of the contract before is has been agreed upon.

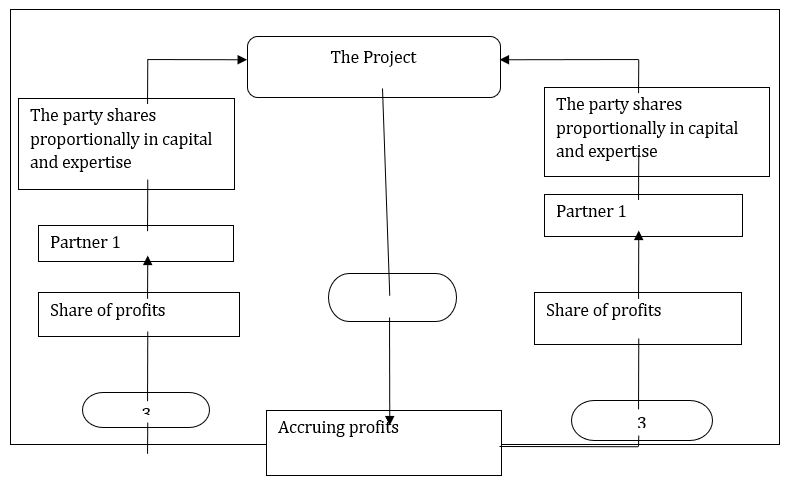

Normally, musharaka contracts involve capital contribution that is inform of cash, even though contribution of capital in form of services is also admissible under sheriah tenets including what is referred as wujuh, to mean “partnership in goodwill”. The fact that musharaka contracts is among the most common method of financial products is certainly not by accident considering that it is one of the most straight forward form of contract under Islamic laws. In musharaka contracts, the capital contribution from each party is normally quantified and a framework of profit and loss sharing (which is usually in proportion to the contribution) between all the parties to the contract drafted based on mutual agreement. A typical example of a musharaka contract is depicted below that ideally involve the IB and a client.

In the musharaka process that is depicted above what normally happens is that the IB which in this case is an equal partner with another party who might be a client enters into a contract that involves financing of a particular project. Once the project has been finalized, the resulting profits or loss in that case will be shared among the parties proportionally as originally pre-agreed during the enactment of the contract.

The securitization of musharakah is also undertaken in similar manner and is the mode of generating huge liquid capital that is preferred by governments or large corporations that require injection of massive capital on a particular project. In this case what therefore happens is that musharakah shares are floated of particular values indicated in the share certificate which the government or a private Company exchanges in return of contribution of funds. The party to a musharaka contract who is actually an investor retains the musharakah certificate that represent the capital contribution of that party to the project venture and consequently the expected value of return on capital in monetary terms (Obaidulah). This would imply that the party to a musharaka contract has therefore the lee way to transfer the ownership of this musharakah certificate to a third party either at par value or at a premium.

The circumstances in which a shareholder to a musharakah contract can opt to transfer the certificate to a third party at par value or at a discount are different for each of this case. Shariah law requires that exchange of monetary assets be made at par where the elements of exchange are both in cash; thus, where the shareholders contribution has not yet been channeled through the intended capital in order to generate the envisioned earnings that necessitated the securitization process in the first place, then the musharaka shareholder can only transfer such share certificates to secondary market at par without charging any form of premium. Besides, the fact that this is mandatory under the Islamic laws serves to prevent financial risk of investors money that would result whereby the value of the liquidity capital would be less than the worth of musharakah share in the market which would be the case if premium was charged upon transfer while no generation of profit was taking place.

However, if the liquidity capital has already been channeled towards a project that was already generating earnings, it is permissible for the musharakah to trade on the certificates of shares in secondary market at a premium. A confusing scenario that often happens when it comes to musharakah securitization is where the initial generated capital is invested in part. This means a proportion of what was originally contributed has not yet been utilized while another certain percentage has been used to obtain assets. This scenario remains contentious among Islamic jurists and there are conflicting positions as whether such musharakah certificates can be traded in secondary markets at a premium or not.

Securitization of Istisna

Istisna is a form of contract financing that is very similar to salam in that the nature of istisna contract is finalized before the completion of the project which occurs in future (Obaidulah). The difference is that while salam involves commodities and tradable goods, for istisna the subject of the contract usually involves the financing of a project. Basically, Istisna is a contract between two parties; a buyer and a seller interested in obtaining an asset in future which would require the seller to use their expertise to either manufacture, process or construct the product.

In this arrangement of istisna contract the role of an Islamic bank therefore becomes that of a financier responsible for bankrolling and therefore facilitating the completion of the project. The parties to an istisna contract have the responsibility for each other to prevent the element of gharar in the transaction process by ensuring that the articles of the contract and specifications of deliverables are clearly spelled out and understood by the supplier. Because istisna contract usually involves delivery of capital intensive projects that are complex in nature, various conditions that pertain to the terms of the contract such as delivery time and duration of repayment are not bound by any Islamic shariah laws.

This makes istisna contracts one of the few contract financing that is not tightly regulated by any set of Islamic laws; in fact the initial capital that must be advanced by the bank towards the financing of the contract does not even have to be made on spot or as a onetime payment as is the case of salam contracts for this is also left at the discretion of the parties. The important elements in an istisna contract therefore remains issues of delivery schedule, as agreed between the parties and the final purchase price that the seller would demand upon completion. Thus, like a murabaha contract the bank finances the project on behalf of the client who will be the obligor in this case; after the obligor reviews and approves the specification of the project the supplier start working to deliver it. This would be what is termed as parallel istisna (Obaidulah).

The process of istisna contract therefore goes as follow; the IB enters into a contract with the obligor in an arrangement that makes the IB the financier and the obligor the agent or the supplier as we shall see. Depending on who the obligor is in this case, the payments are passed on to the manufacture or obtained directly by the supplier who implements the terms of the contract. From this point the ownership of the asset will depend on the nature of agreement that would have been previously agreed between the parties which could be either a lease agreement or a form of forward lease agreement (Obaidulah). In parallel istisna contracts mentioned above, it is mandatory that an IB enters into two different contracts with different parties so as to separate the supplier and the client and in the process be able to obtain the profit mark-up that it requires.

Basically the reason that would make a bank agree on parallel istisna does not necessarily have to do with a need of obtaining mark-up profit since this is also obtained through the ordinary istisna contracts, but rather because of the fact that the bank does not have the ability to manufacture the product or that it does not wish to hold on to the asset after it has been completed (Obaidulah). Hypothetically, what therefore happens is that a bank assesses the feasibility of obtaining certain assets on behalf of the client, referred here as mustasne who becomes party to the first istisna contract in which it becomes party to it. The bank then takes the specifications of the assets referred as masnou as outlined by the mustasne that need to be manufacture and obtains the quotation for manufacturing and availing the assets to the banks; a second parallel istisna is also entered.

The difference in price that the bank institute in transferring the assets to the client constitutes the profit mark up that the IB obtains from the parallel istisna contract. As we can see, a special feature that is unique to all forms of istisna contracts is that they involve manufacture or construction of assets of pre-agreed specifications which is the reason that they are referred as “commissioned manufacture” (Obaidulah).

The process of securitization that results from financing of istisna contracts is diagrammatically depicted below which elaborates clearly the concept of both ordinary istisnaa and parallel istisna.

Securitization of istisna is therefore one of the most widely used methods by IFIs to obtain liquidity capital on behalf of the bank because of the huge potential capital that is involved in financing istisna projects which translates to significant profit margin that the bank stand to attain. The fact that istisna is a form of fixed-return financing means that the investors gets to obtain what Gurulkan describes as “residual rights of control and management to users” that results from their capital investment (Gurulkan). Because of this advantage investors are normally eager to finance such types of projects that offer fixed-return which implies that the IBs tend to provide more capital financing for such projects; this results in securitization process of istisna contracts becoming even more heightened.

The downside of istisna contracts on the other hand results from the fact that the resulting istisna certificates are essentially a form of debt securities which makes them untradeable at secondary market because of the shariah law that prohibits their transfer at a premium, except of course in Malaysia. The Islamic principle that governs all forms of istisna contracts is referred as Istihsan which means it is a financing method that is necessary due to public interest. Indeed, the major projects in which istisna structures have traditionally been used to finance would confirm this assertion. Generally istisna structures are the mode that are most preferred when it comes to finance of the following projects; in construction industry it usually used in construction of facilities such as hospitals, schools, housing projects and financing of technologies.

References

Alkhan, Khalid. Islamic Securitization A Revolution in the Banking Industry. Abudhabi: Miracle Graphics Co., 2006

Ayub, Muhammad. Understanding Islamic Finance. London: John Wiley & Sons Ltd, 2008.

Basel.org. A New Capital Adequacy Framework.Consultative Paper Issued by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, 2000. Web.

Chapra, M. Umer, Challenges facing the Islamic financial industry: Handbook of Islamic Banking. ed. by Hassan, M. Kabir & Lewis, Mervyn K. Northampton, US: Edward Elgar Publishing, Inc., 2007

El-Gamal, M. Islamic Banking Corporate Governance and Regulation: A call for Mutualization, 2005. Web.

El-Gamel, M. Islamic Finance, 2006. Web.

FederalReserve.org. Federal Reserve Statistical Release Z.1: Flow of Funds Accounts of the United States, Flows and Outstandings, Fourth Quarter 2006. Web.

Gurulkan, H. Islamic Securitization: A legal approach, 2010. Web.

Hassan, M. Issues in the Regulation of Islamic Banking: The case of Sudan, 2004. Web.

Hassan , M. & Lewis, M. Islamic banking: an introduction and overview: Handbook of Islamic Banking. Northampton, US: Edward Elgar Publishing, Inc., 2007

Kayed, R. & Kabir, H. Islamic Entrepreneurship. Riyadh, Routledge. 2008

Kettering, K. Securitization and its Discontents: The Dynamics of Financial Product Development. Cardozo Law Review, 29.4(2008): 1555-1598

Timberg, A. Risk Management: Islamic Financial policies. Islamic banking and its Potential Impact, 2000. Web.

Obaidulah, M. Securitization in Islam: Handbook of Islamic Banking. ed. by Hassan, M. Kabir & Lewis, Mervyn K. Northampton, US: Edward Elgar Publishing, Inc., 2007

Shenker, C. & Colletta, A. Asset Securitization: Evolution, Current Issues and New Frontiers, 69 (1991): 1369, 1370-88.

Zaher, T. & Kabir, H. A Comparative Literature Survey of Islamic Finance and Banking. London: John Wiley & Sons Ltd, 2004