Introduction

Literate and educated people form the fundamental platform for economic development because they are able to obtain meaningful formal employment in addition to being self-employed and creating employment for others. Armstrong et.al (2010) indicates that in South Africa, a single national educational system exists managed by the national Department of Education.

The national system consists of nine provincial systems. The three stages of general education and training (GET), further education and training (FET) and higher education (HE) make up the educational system.

Context of Education in South Africa

It is important in considering the context of development of South Africa when analysing the country’s issues of development concentrated on education. According to the UNDP (2010), South Africa is a middle-income country that depends less on foreign aid, instead it relies on successful mobilization of domestic resources to finance its education and other government policies.

The country has a total population of approximately 49 million comprising of 18 million youths between the ages of 15 to 34 years. The international Monetary Fund classifies South Africa as the 25th –largest economy by GDP and this makes it the biggest economy in Africa (Armstrong et al. (eds.) 2010).

South Africa’s education policy is in line with the millennium development goals of achieving universal primary education by the year 2015.

In 2007, South Africa had 387,000 educators and 26,592 schools that consisted of about 400 special need schools and 1000 private schools. There were only 6000 secondary schools in the same year. 98.4 per cent of total country population of boys and 98.8 per cent of total population of total country population of girls were enrolled in schools in 2002.

As of year 2002, South Africa’s education system had a population of 12.5 million people and out of these; 7.5 million students were enrolled in primary education, 4.3 million students were enrolled in secondary education there were 675,160 students in tertiary education.

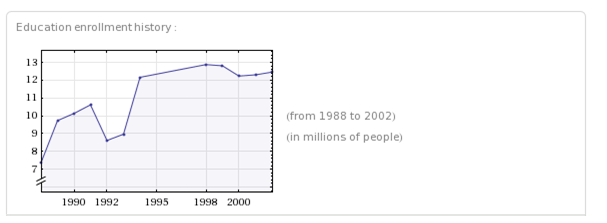

The education enrolment in South Africa has steadily risen from 1990 to year 2002 except or year 1992 and 1993. The enrolment level into the education system has stabilized at the twelve to thirteen million students’ level as illustrated in the graph below (UN Data n.d.).

Rural public schools differ in their urban counterparts in terms of infrastructure. About 27 per cent of public schools have no running water while 78 per cent lack libraries and a similar percentage lack computers. A majority of these disadvantaged schools are located in the rural areas of South Africa.

Inferior facilities of rural schools especially farm schools disadvantage students by providing a relatively poor quality education that have to sit for exams set in conditions having a relatively perfect education infrastructure. Most private schools are located in urban areas and have an educator to learner ration of 1:20 while public schools in rural areas have a ration of 1:33.2.

The South African government funds public schools however only schools in poor population areas are free. Key challenges facing the education system of South Africa are the increased diversity of educational institutions that require a further teaching of educators to learn to cope.

Secondly, the increasing need to use technology to facilitate education and relieve strain on educators in addition to cost associated with deployment of the technology. Lastly, socio economic challenges of students affect their enrolment and stay in school and so does customs and tradition such as those favoring early marriage of girls (SouthAfricaWeb n.d.).

Handling of Educational Challenges in South Africa

The UNDP (2010) Millennium Development Goals report indicates that after attainment of independence in 1994, South Africa started a pursuit of constitutional protection measures that guarantee a right based environment and to achieve this aim, the South African government launched systematic approaches to remove socioeconomic associations of apartheid and replace it with an equitable, non-racial and non-sexist society.

One systematic approach used by the government is the five year Medium Term Strategic Framework from 2009 to 2014 that notes all threats to development facing South Africa and forms the basis of all intervention policies to improve the living standards of South Africans including their education.

The government’s expansion of the provision of infrastructure, facilities and resources for learning at primary and secondary schools has resulted to more schools receiving libraries and science laboratories (UNDP 2010). According to the UNDP (2010) report, South Africa’s anti-poverty strategy includes a compulsory free education policy for all 7 to 13 year olds.

Because of this initiative, school enrolment for the same age group improved from 96.7 per cent in 2002 to 98.4 per cent in 2009. The functional literacy rate measured by attainment of primary education up to grade 7 has improved from 88% in 2000 to 91% in 2009 (UNDP 2010).

Furthermore, that of 15-24 year olds has also improved with the number of those not functionally literate falling from 13% in 2002 to lower than 10% in 2009.

Women’s lack of decision-making ability in families and households makes them poorly equipped to safeguard education for their children (UNDP 2010). Early marriages also decrease the chances of women to complete their education and ensure that their children receive appropriate education. Class repetition threatens the completion of primary education as pupils get older.

According to Nhantsi (n.d.) Girls Education Movement (GEM) is an intervention to reverse the bias against girls in education that was launched in South Africa in 2003, comprising of children in school and communities working in several ways to ensure that girls receive adequate education with a special emphasis on science and mathematics.

The GEM transforms schools into environments providing equal opportunities for girls (Nhantsi n.d.).

To enable 4.7 million South Africans become literate by 2012, a mass education campaign named Kha Ri Guide Mass Literacy Campaign was initiated in February 2008 by the Department of Education of South Africa. The campaign pilot involved 360,000 learners and in 2009, the campaign reached 620,000 learners.

Notably, 8% of the participants were disabled while 80% were women; additionally the campaign offers materials in braille to be used by the deaf. The program was expected to result in a million new literates by the end of 2009.

Budgetary allocation for the campaign was R436 million in 2009 compared to R458.6 million in 2008, while per capita costs lowered to R680 from R1280 that was achieved by increasing the learner to educator ratio to 18:1.

Higher education in South Africa is faced with the challenges of increased diversity, claims for transparency and accountability, technological impacts, academic employment changes, an increasing number of education providers, a need to stay internationally competitive and laying a focus on bench marking and performance indicators (Strydom & Strydom 2004).

South Africa suffers brain drain because of commitment to international agreements that treat education as a commercial trade service that should be unrestricted by any trade barrier. Terms governing the international agreements are discussed without adequate inputs from African countries and lead to making of commitments that are not in their favour.

Higher education is South Africa falls under the framework of the SADC Education Protocol that promotes equivalence, and harmonization of education standards in the region.

Therefore while in the 1990s education policies aimed at defining higher education transformation agenda, the years after 2000 have seen the ministry of education having to make necessary trade-offs for key policy issues to comply with regional policy issues of the SADC.

To assure quality of higher education, the Commission of Higher Education (CHE) was initiated in year 2000. Among the challenging needs facing higher education in South Africa, divisions caused by the country’s past are the most difficult to solve. An initiative taken to solve this challenge has been to merge different institutions and universities with different technical colleges to come up with new universities (Strydom & Strydom 2004).

An increase in tertiary education facilitates technological catch up that improves a country’s ability to maximize its economic output.

According to Bloom, Canning and Chan (2006), if South Africa increases its stock of tertiary education by a year, then it would be able to overcome the 23 per cent points needed to move beyond its current possibility frontier. An extra year of tertiary education has the capacity to increase per capita income growth in the first year by 0.63 per cent and by 3 per cent after five years.

According to the South African national budget for 2008/2009, education expenditure got an allocation of ZAR121.1 billion out of a total budget of ZAR716 billion signalling a more than 5 per cent expenditure of national budget on education, however the figure is lower than UNESCO’s recommended figure of 6 per cent for developing countries (Armstrong et al. (eds.) 2010).

Conclusion

Before the decade, starting year 2000 South Africa did not have to align its policies with regional and international bodies. However, as the country signs up for international cooperation, it is forced to formulate policies that ate in line with international best practices while still ensuring that its indigenous needs such as gender equality and technological advantage are incorporated (Teferra & Knight (eds.) 2008).

Reference List

Armstrong, C, Beer, JD, Kawooya, D, Prabhala, A, Schonwetter, T (eds.) 2010, Access to Knowledge in Africa: The Role of Copyright, UCT Press, Claremont.

Bloom, D, Canning, D & Chan, K 2006, ‘Higher Education and Economic Development in Africa’, Research Paper, Harvard University, Boston, MA.

Nhantsi, A, ‘Girls, Schools and Statistics Education in South Africa’, 1st Africa Young Statisticians’ Conference, Statistics South Africa.

SouthAfricaWeb n.d., Primary and Secondary education in South Africa. Web.

Strydom, AH & Strydom, JF 2004, ‘Establishing Quality Assurance in the South African Context’, Quality in Higher Education, vol 10, no. 2, pp. 101-113.

Teferra, D, Knight, J (eds.) 2008, Higher Education in Africa: the international dimension, Boston College Center for International Higher Education, Chestnut Hill, MA.

UN Data n.d., South Africa. Web.

UNDP 2010, ‘Millenium Development Goals, Country Report: South Africa’, Country Report, Republic of South Africa, UNDP.