Introduction

At first glance, it would appear that Kenya and Brazil are very different. Kenya has much less land mass than Brazil. However, much of Brazil’s land mass is not arable land. Both countries have a large population sector, which lives in abject poverty. Environmental degradation is a major problem in both of these countries, caused by deforestation, population increase and industrialization with all their attendant pressures upon the environment.

While the land type is very different, the results are the same. The two countries have similar problems stemming from similar causes. The problem in Kenya is much worse than that in Brazil, because poor governance has allowed Kenya’s problem to approach the point of no return. Politically, these two countries are both democratic republics. However, Kenya has carried the weight of the same corrupt government for the past 20 years. This paper will compare and contrast these two countries and their particular environmental problems and conflicts arising therefrom. Will also examine possible resolutions.

Kenya’s Situation

Wangari Muta Maathai accepted the Nobel Peace Prize Friday in Oslo of the key people. Maathai was born in Nyeri, Kenya in 1940. She began by planting a few backyard trees, and by the 1990s this had grown into the Green Belt Movement, movement which focused on environmental conservation and the sustainable development of communities. At this date more than 20 million trees have been planted by women on their farms in schools and churches. This movement has been exported to almost a dozen other sub-Saharan African countries, and the United Nations and governments of several European countries as well, have contributed more than $5 million annually to push this movement forward.

In her acceptance speech for the peace prize, Maathai commented that over the years she has learned that the state of any country’s environment is merely a reflection of the kind of governance in place in that country. Poor environmental laws and conflict seem to go hand in hand in these cases.

Kenya recently unseated President Daniel Arap Moi, during whose 20-year reign corruption was rife, and replaced him with Mwai Kibaki, an economist with a spotless reputation. During the last 20 years, Maathai had been detained, interrogated, arrested and beaten in an effort to discredit anyone associated with the country’s pro-democracy movement.

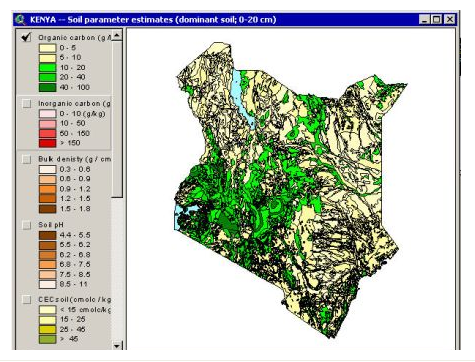

His population of 35 million amounts to 54 people for every square kilometer of land. With this kind of population pressure, much of the original land is no longer in its native state. Kenya has a coastline equal to approximately 1/8 of its total border. This fragile ecosystem is being decimated by rice farming, salt pans, aquaculture, and urbanization. Mangrove trees are dying out and water is being polluted by pesticide runoffs, and urban and industrial waste.

Slash and burn techniques were start Kit for farming more than a hundred years ago, and by this time. have decimated virgin forest. Loading for fuel and construction has been responsible for the rest of the loss. The loss of this forest is aggravated erosion, contributed to the loss of biodiversity and been responsible for the silting up dams and flooding. (Whyte, 1995)

This loss of habitat has contributed to the species loss already aggravated by illegal hunting and open armed conflict in the region. The fisheries have been decimated by poor fishing practices, trawling and dragged netting, which destroys the coral and the sea grass areas. All over the country streams have simply disappeared and lakes have been overrun with infestations of foreign imported species which are choking out the fishing. Poor water and land management have created an environmental crisis fueled by rapid population increase. These scarce resources became controlled over the past 20 years by the corrupt government of Daniel Arap Moi.

Brazil’s Situation

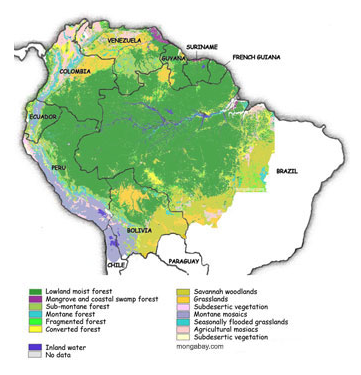

It’s time to look through this Brazil’s population is approximately 178, 470, 000, with a population density of 20 people per square kilometer. Still, the pressure is not much different from Kenya, since a large portion of Brazil’s land is occupied by dense rain forest, and is really not suitable for farming. Brazil’s forests have been decimated by slash and burn by poor farmers seeking to increase their land. However, the land does not support regular crops, and is completely depleted after only one year. In recent years, other interests have been clearing forest, such as sugar cane producers. While governments in Brazil was marginally better than that in Kenya, the scarce resources were controlled by plantation owners, and the affluent elite.

Very recently, the Brazilian government initiated a no tolerance policy to protect the Amazon rain forest, which is a mere 8% of its original size. On the first of July, the government fined 24 ethanol producers a total of 75 million US dollars for a legally clearing forests in order to establish sugarcane plantations. In addition, those companies will now be required to restore the forest as close to its original state as possible. The government is supporting recent deals signed with foreign governments, such as Sweden, to export sustainably produced ethanol. In light of the abominably expensive fuel oil, biofuels are seriously being looked at in Brazil and in Kenya as viable alternatives and for export.

Brazilian authorities in recent months are taking a hard line against loggers, ranchers, farmers and charcoal producers who are violating environmental laws. 3000 head of cattle were seized recently when they were found illegally grazing on deforested Amazon land.

The cattle were confiscated and sold off to support programs to feed the poor. (Mongabay.com 2008) this is an effort by the Brazilian government to counter the criticism from other countries concerning the recent and in the neighboring ecosystems where analysts say rising commodity prices are linked to this deforestation. Brazil noted that the deforestation rate was down from 2004, but that more effort is needed. One of the major problems is that Brazilian mass-produced biofuel is extremely efficient when compared with US corn ethanol. An economically viable product, contributing thereby to the illegal destruction of the Amazon rain forest.

Similarities

Both of these countries are under severe population pressure, especially the pressure of increased populations of poor. Deforestation is a primary factor in the degradation of the environment in both Kenya and Brazil. Slash and burn subsistence farming is one of the factors involved. Industrialization contributes to the degradation of water and land resources with pollutants and waste runoffs. Urban populations, increasing at a rapid rate, degrade the water further with untreated sewage. Very marginal land has been taken from its natural state, and put into service to create crops, which are marginally useful at great cost to the environment. The resulting depletion of the soil makes this now barren land unusable for anything, including its natural state. These parallels exist between the mangrove swamps and the Amazon rain forest, especially.

In both countries, the political situation has been peaceful, but not in the best interests of the majority of the people. Power structures, saw to it that scarce resources were diverted to the powerful elite. Sadly, few people paid much attention until the wolf was literally at the door. Another parallel between these two countries. Is there political structure. Both countries are presidential republic’s. However, powerful economic interests promoted poor governance in addressing the problems of environmental degradation over the past 20 or so years.

Differences

One of the major differences between Kenya and Brazil is the state of the crisis. While the status of the rain forest in the Amazon is definitely critical, it has not reached the point of no return. The damage is not irreversible as has been proven by recent initiatives to return damaged land to its original version forced state. While certain education in the rain forest takes many years to grow, such as the large tree which produces the Brazil nut, which often is aged 30 years before it produces.

The ecological center of production areas in the Amazon rain forest is often a 500 year old Brazil nut tree. However, the abundant rain and climate makes it a little easier to recapture this land than that in Kenya.

The virgin forest in Kenya that has been raised by a slash and burn subsistence farming and commercial enterprise, plus expansion of urban populations does not have sufficient rain to return it to its natural state without extreme intervention. The Green Belt Campaign in Kenya is aimed at replanting literally millions of trees. However these have to be cared for, until they are mature enough to survive without intervention. Regardless of the strength of this movement, it will be many years before it begins to show tangible results.

The status of the mangrove swamps is much more critical. To return this land to its original state would require a political initiative to displace the current rice farmers and aquaculture farmers, possibly compensating them and moving them elsewhere and an unbelievably huge effort and expense to clean out the silt and replant the mangroves. However, the results of lane changes in Mississippi previous two hurricane Katrina were strong contributors to the massive damage of the flooding caused by the collapse of the artificial levees. Study since hurricane Katrina have shown that the flooding would have been nowhere near as devastating had the buffer swamps been left in their natural states.

Research in Florida is producing the same results. Coastal areas of mangrove swamps are extremely valuable to local ecosystems. The fish populations in the bordering waters often depend on these swamps for breeding areas. In addition, the Swamp represents a buffer between salt water and fresh water. The plants and animals which live in this ecosystem are uniquely situated to survive in such an area. All along the eastern coast of the United States, Georgia and the Carolinas, in particular, governments are initiating legal restrictions on the conversion of these sorts of lands, and even funding to purchase of converted lands in order to return them to their natural state.

Resulting Environmental Conflict

As Maathai pointed out earlier, governance is the key to environmental protection. Poor governance is notoriously shortsighted. Environmental degradation impacts the populations by promoting the scarcity of resources. Scarce resources create conflict. The conflict can be resolved generally only by intervention of a strong internal or external influence. In both of these countries, the primary influences internal, creating a grassroots initiative for change.

“There are three types of environmental scarcity:

- supply-induced scarcity is caused by the degradation and depletion of an environmental resource, for example, the erosion of cropland;

- demand-induced scarcity results from population growth within a region or increased per capita consumption of a resource, either of which heightens the demand for the resource;

- structural scarcity arises from an unequal social distribution of a resource that concentrates it in the hands of relatively few people while the remaining population suffers from serious shortages.” (Diehl & Gleditsch, 2001, p. 14)

Homer-Dixon (1994) tells us that there are generally two patterns of interaction for these three types of scarcity: resource capture and ecological marginalization. By resource capture, we mean that the increased consumption of the resources and powerful groups within the society will capture that resource in anticipation of future need. The resources than become more scarce for those population sectors not in power. In other words, the rich get richer and the poor get poorer. This is generally accomplished by a combination of political and economical power. When these won’t suffice, the situation generally declines into armed warfare

Ecological marginalization causes the movement of the population sectors not in power into the more marginal areas as resources become scarcer. These marginal areas are generally ecologically fragile, and this increases the environmental degradation. This becomes a self-perpetuating problem until the marginalized population either dies out or resorts to armed conflict. ( Homer-Dixon, 1994: 15-16).

In Kenya, the ecosystem on the coast is mangrove swamp, creating a buffer area where fresh and salt water mix. Because less than 20% of Kenyan land is arable, these areas have been taken over the rice fields and aquaculture. This has eliminated what has been found to be an environmental the necessary buffer area after studies done following hurricane Katrina. Swampland was seen by the farmers as wasteful and unnecessary. However, environmental research has shown that these areas are absolutely necessary to keep coastlines from eroding.

The lack of enough rainfall for farming in Kenya has promoted the diet version and subsequent pollution of water resources. ( Coetzee and Cooper, 1991: 130) organic matter content, music crops have to be moved frequently as the landmass is depleted. While Brazil has plenty of rain, its landmass is also low in organic matter after slash and burn techniques have been applied, and the poor Brazilian farmers face the same problem of having to move their crops each year. Repeated cultivation of the same land creates the problem of the erosion and silt buildup in the mouths of rivers and the images of swamps. ( MacKenzie, 1994: 2).

Deudney points out (1991) that political efforts to link environmental issues and security partly motivated by the need to draw attention to the environmental issues. This is inspired, new research between environmental degradation and conflict. This has resulted in the rapid increase of research concerning the struggle for access and control of natural resources. ( Brock, 1991 ; Brundtland et al., 1987; Choucri and North, 1975; Galtung , 1982; Gleick, 1993b; Homer-Dixon, 1991, 1996; Homer-Dixon et al., 1993; Lodgaard, 1992; Opschoor, 1989; Percival and Homer-Dixon, 2001; Renner et al., 1991),

There have been questions concerning the arguments about the role of resources and environmental factors in the creation of conflict ( Deudney, 1991; Gleditsch, 2001; Levy, 1995). Problems that resulted from the fact that there have been few studies which were able to use a control group, considering that where there is armed conflict there’s no possibility of establishing the control group without the armed conflict.

The impossibility of allowing for this variability is a common occurrence in sociological and anthropological research. Therefore, the research is decidedly one-sided. Homer-Dixon made allowances for this by choosing a different methodology of process tracing within the context of case studies relying therefore on qualitative analysis, rather than quantitative. The researcher states, ‘in the early stages of research, process tracing is often the best, and sometimes the only way to begin’ ( Homer-Dixon, 1995c: 8). Another problem cited by researchers is the failure of research projects to consider other possible causes of armed conflict rather than environmental pressures.

The Role of Governance

Governance is commonly seen as both the cause and the possible resolution of environmental conflict. Because of this, Kenya’s government recently underwent a change, electing a new leader seen to be honest, politically incorruptible and environmentally and so sociologically sensitive. Brazil’s government, are composed of much the same as before, has slowly been approaching this problem over the past 20 years, and is now reacting to popular pressure with the aid of worldwide forces in concert.

Many researchers, such as Chan, Russert and Starr, believe that there is extremely strong evidence that democracy promotes peace between nations. They cite the fact that democracies almost never wage war against each other, especially not since World War II ended ( Chan, 1997; Ray, 1995; Russett, 1993; Russett and Starr, 2000).

There are studies under way. Looking at the possibility if democracy can have other positive effects, specifically the promotion of environmental consciousness and the creation of environmental movements to minimize the damage from overpopulation, industrialization and poor environmental initiatives. These would extend to minimizing soil degradation, protecting freshwater supplies, and the proper husbanding of the land in its natural state. By minimizing the scarcity, thereby, and by mandating or equitable sharing of these resources is thought that civil conflict may be avoided (Homer-Dixon 1994).

A group of scholars for promoting the idea that environmental degradation or resource scarcity can lead to violent conflict in includes Homer – Dixon (1991, 1992, 1994), Klötzli (1997) and Libiszewski (1997), among others. These and other scholars are now investigating the possibility of the prevention of violencewhich is aggravated by environmental scarcity through governance and intervention. Thomas Homer-Dixon ( 1991: 88) indicated a desire to ‘help identify key intervention points where policy makers might be able to alter the causal processes linking human activity, environmental degradation, and conflict’. In the same article, he argues against placing ‘too much faith in the potential of human ingenuity to respond to multiple, interacting, and rapidly changing environmental problems once they have become severe’ ( Homer-Dixon, 1991: 103-104).

It has been found in that waiting until conflict has arisen is unacceptably dangerous. Instead, governments need to act positively to prevent and prepare environmental degradation. Prevention strategies, historically cost a whole lot less than repairing the damage, both to the land and the populations occupying it, should armed conflict be allowed to arise.

In addition, some types of environmental degradation, such as the destruction of fish stocks or tropical forests and the pollution of water and land by pesticide and fertilizer runoffs can reach a point where they become nearly irreversible. It is conceivable that if enough locations around the globe reached this level. The degradation could have the domino effect of collapsing nearby resources.

However, traditionally human populations seemed to become trapped by the “hole in the roof” syndrome. When the sun is shining, a whole doesn’t need to be fixed. When it’s raining the whole can’t be fixed. Hardin calls this a ‘Tragedy of the Commons’ 1968) pointing to the problem of overcoming individual interest in exploiting the environment.

In addition, there is another psychological factor which can be illustrated by the problem, which occurred in Mongolia several years ago. (personal conversation with Mongolian resident via MSN chat) in Mongolia, cooperative farming has been used for centuries. Sheep ranchers would establish their ranches around the grassland, encircling it. The land was open range, so the sheep ranchers shared it. Typically, five branches would surround a grassland capable of supporting approximately 20 to 30 sheep.

This worked until one farmer decided to buy another sheep or two in an effort to increase his profit. Since he saw fit to increase the herd, the other cooperating ranchers subsequently increased their herds, because it was seen as unfair that he could increase his and they could not increase theirs. This put intolerable stress upon the land. Making matters worse, some ranchers decided to add goat’s, which tend to destroy the grassland where they graze by cropping the grass to close or literally pulling it out by the roots.

The end result of this was that the open range became unusable, the grass died and the winds blew away the thin layer of topsoil. This contributed to the dust storms that have been plaguing Beijing. Since the Chinese government can issue an edict and expect to be instantly obeyed, new laws were made to correct this situation. In addition, ranchers were paid to seed wild grasses and allow the land to return to its wild state. This intervention is gradually reducing the erosion in the province of Mongolia.

Environmental Dispute Resolution

This new form of conflict resolution encompasses a variety of approaches to allow stakeholders to meet face-to-face and come to a mutually acceptable resolution of the issues in dispute, or the controversial situation ( Bingham, 1986). McCrory (1981) points out that this is often viewed as intervention between the parties disputing or the viewpoints in order to effect reconciliation, settlement, compromise or at the very least, understanding among the various parties. Sometimes it only requires a bit of assistance in negotiation process from a third party ( Bingham et al., 1987). It is generally believed that this third party should be neutral. The negotiations may be directed towards settling past disputes or in setting up rules to establish governance for future conduct. ( Eisenberg, 1976).

Possible Resolutions

Regardless of the differences between the status off the land in Kenya and that in Brazil, the possible solutions are similar. In both cases, assistance from other countries will be necessary. Organizations such as the World Bank and the United Nations can help to fund the necessary changes. Kenya is traditionally a poorer country than Brazil, and it has certain other problems among the population, which are not as widespread, such as the occurrence of HIV and AIDS.

It is certain that no one solution alone will resolve these problems. The causes are varied, but generally based on the scarcity of land and resources. Therefore, equitable distribution needs to be promoted for the available resources. In addition, available resources need to be increased. Population problems need to be addressed. Foreign governments need to cooperate with these governments in applying sanctions against their own companies, who feel free to devastate someone else’s land. Commercial interest is generally at the root of most of the current destruction.

In both countries, that land which cannot be returned to its virgin state must be made much more productive, yet in a sustainable manner. The technology to do this efficiently requires an initially high investment. It will also require a great deal of research in the development of more sustainable methods of production. This should be a worldwide effort. Proper use of land that cannot be returned to its original state could increase production up to 20 fold in the Amazon, and somewhat less so in Kenya, but enough to make it an attractive initiative.

A study of the techniques of ancient civilizations in enriching the land can help the supply more sustainable methods. The use of urban waste to enrich the land and the use of biomechanical methods of water treatment, such as the Florida initiative using water lilies, can benefit the environment and create new jobs. The research into the use of waterlily showed that the water lilies were completely clean the water, and the plants could then be harvested to create biofuel. This is a possibility in areas which are now being used for rice production in Kenya.

Habitat and species preservation is another area that will need attention. These are interdependent, so the expansion of preservation areas will require the protection and even assistance of the species which generally occupy that niche. This would be the Brazil nut tree in Brazil and the mangrove in Kenya. As initiatives are developed to help the poor populations of these countries, preservation areas can be expanded and protected.

One interesting area, which could stand more attention is the issuance of microloans to people in poor populations to help them develop sustainable projects to support them. It has been shown that raising the standard of living among poor populations results in an equivalent reduction in population. As people standard of living rises they need fewer offspring to support them in their old age.

Sustainable development may be the cornerstone for the recovery process for these ecosystems. The Brazilian government is already initiating programs in this area. The new government of Kenya needs to create some for itself. The production of biofuel using already cleared land is possibly a viable alternative if production can be increased using sustainable methods. The development of new products which are native to the Amazon rain forest and the Kenyan forest and mangrove swamps will promote the restoration and preservation of these areas.

New methods need to be developed for logging and cattle ranching, and possibly even rice production and aquaculture, which are not damaging to the ecosystem. These are key to maximizing land-use and minimizing ecological damage. In addition, government subsidies and tax incentives need to be removed, while expensive sanctions for illegal actions and use need to be increased and enforced.

These countries cannot do this alone, so other countries will have to partner with them for the good of the global ecosystem. Any conflict on this planet is bad for the rest of the planet. It doesn’t matter if we’re the conflict is it impacts the entire planet. If intervention comes in the form of cooperation and investment, it will be welcome.

Conclusions

There are more similarities between these two countries and their ecological crises than there are differences. The differences consist of the amount of land mass and population, and the geological attributes of the two regions. There is a large difference between the rainfall, as most of Kenya’s land just simply does not get enough rainfall, much of the Amazon gets a bit too much.

However, the state of the water quality, the utility of the land in, other than its natural state, the problems with urban and industrial waste and chemical runoff and the commercial interests which have been devastating these two countries for too long, are problems they have in common.

The solutions too are very similar. The real require outside intervention, at the very least help with negotiations and financial support. In addition, they will need support for any initiatives for which they find the political will. The developed countries of the world can help by providing expertise, funding and research. In addition, countries which will benefit from developing sustainable commercial enterprises in these areas should invest in supporting them.

While providing expertise in research, developed countries can also serve as role models by cleaning up their own acts. Conflict resolution in these very ecologically challenged areas should be preemptive, preventative and forward thinking. It is a whole lot easier to support a peaceful the developing country than it is to repair the damage done after conflict arises over scarce resources. One suggestion might be to create a world ecological Association, whose mandate it would be to track problems in ecologically vulnerable areas and create a worldwide cooperative to help with the support and application of solutions before they are needed.

References

Bingham G. and L. Haygood, “Environmental Dispute Resolution: The First Ten Years.” The Arbitration Journal, 41 ( 1986): 3-14.

Bingham Gail. Resolving Environmental Disputes. A Decade of Experience. Washington, D.C.: The Conservation Foundation, 1986.

Bingham Gail, Frederick R. Anderson, R. Gaull Silberman, E. Henry Habicht, David F. Zoll , and Richard H. Mays. “Applying Alternative Dispute Resolution to Government Litigation and Enforcement Cases.” Administrative Law Review, 1 (1987): 527-51.

Blackburn, J. Walton; Bruce, Willa Marie. 1995 Mediating Environmental Conflicts: Theory and Practice. Quorum Books.

Brock, Lothar. 1991. “‘Peace Through Parks: ‘”The Environment on the Peace Research Agenda, Journal of Peace Research 28( 4): 407-423.

Brundtland, Gro Harlem, et al. 1987. Our Common Future: World Commission on Environment and Development. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Butler, Rhett A. 2008. Deforestation in the Amazon. Mongabay. Web.

Chan, Steve. 1997. “‘In Search of Democratic Peace: ‘”Problems and Promise, Mershon International Studies Review 41( 1): 59-91.

Choucri, Nazli, and Robert C. North. 1975. Nations in Conflict. San Francisco, Calif.: Freeman.

Coetzee, Henk, and David Cooper: 1991. ‘Wasting Water’, in Going Green:People, Politics and the Environment in South Africa, pp. 129-138, ed. Jacklyn Cock and Eddie Koch. Cape Town: Oxford University Press.

Deudney, Daniel H. 1990. “‘The Case Against Linking Environmental Degradation and National Security’”, Millennium 19( 3): 461-476.

_____. 1991. “‘Environment and Security: Muddled Thinking’”, Bulletin of Atomic Scientists 47( 3): 22-28.

_____. 1993. “‘Global Environmental Rescue and the Emergence of World Domestic Politics’”, in Lipschutz and Conca, eds. (280-305).

_____. 1999. “‘Bringing Nature Back In: Geopolitical Theory from the Greeks to the Global Era’”, in Deudney and Matthew, eds. (25-57).

_____. 1999. “‘Environmental Security: A Critique’”, in Deudney and Matthew, eds. (187-219).

Deudney, Daniel H., and Richard A. Matthew, eds. 1999. Contested Grounds: Security and Conflict in the New Environmental Politics. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Diehl, Paul F. 1992. “‘What Are They Fighting For? The Importance of Issues in International Conflict Research’”, Journal of Peace Research 29( 3): 333-344.

_____. “‘Environmental Conflict: An Introduction’”, Journal of Peace Research 35 ( 3): 275-277.

Diehl, Paul F. and Gleditsch, Nils Petter. 2001. Environmental Conflict. Westview Press.

Eisenberg Melvin Aron. “Private Ordering Through Negotiation: Dispute-Settlement and Rulemaking.” Harvard Law Review, 89 (1976): 637-81.

Environmental problems in Kenya. 2008. WWF for a living planet. Web.

Galtung, Johan. 1969. “‘Violence, Peace, and Peace Research’”, Journal of Peace Research 6( 3):167-191. Reprinted in Johan Galtung: Essays in Peace Research, vol. 1: Peace: Research-Education-Action. Copenhagen: Ejlers. (109-134).

Gleditsch, Nils Petter. 1994. ‘Conversion and the Environment’, ch. 7 in Green Security or Militarized Environment.? pp. 131-154, ed. Jyrki Käkönen. Aldershot and Brookfield, Vt.: Dartmouth.

_____. 1995. “‘Geography, Democracy, and Peace’”, International Interactions 20( 4): 297-323.

_____. 1996. “‘Det nye sikkerhetsbildet: Mot en demokratisk og fredelig verden?’ [The New Security Environment: Towards a Democratic and Peaceful World?]”, Internasjonal Politikk 54( 3): 291-310.

_____. 1997a. ‘Environmental Conflict and the Democratic Peace’, ch. 6 in Gleditsch , ed. 1997b (91-106).

_____. 2000. ‘Resource and Environmental Conflict: The State of the Art’, in Responding to Environmental Conflicts: Implications for Theory and Practice, ed. Alexander Carius. Dordrecht: Kluwer (in press).

_____. 2001. “‘Armed Conflict and the Environment’”, ch. 12 in this volume. Revised version of article published in Journal of Peace Research 35( 3): 381-400. 1998.

Gleditsch, Nils Petter, and Håvard Hegre. 1997. “‘Democracy and Peace: Three Levels of Analysis’”, Journal of Conflict Resolution 41( 2): 283-310.

Gleditsch, Nils Petter, and Bjørn Otto Sverdrup. 1996. ‘Democracy and the Environment’, paper presented to the Fourth National Conference in Political Science, Geilo, Norway.

Gleditsch, Nils Petter, ed. 1997b. Conflict and the Environment. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Gleick, Peter H. 1989. “‘The Implications of Global Climate Changes for International Security’”, Climate Change 15: 303-325.

_____. 1993a. “‘An Introduction to Global Freshwater Issues’”, in Gleick, ed. 1993b (3-12).

_____. 1993c. “‘Water and Conflict, Fresh Water Resources and International Security’”, International Security 18( 1): 79-112.

_____. 1994. “‘Water, War, and Peace in the Middle East’”, Environment 36( 3): 6-18.

_____. 1996. “‘Basic Water Requirements for Human Activities: Meeting Basic Needs’”, Water International 21( 2): 83-92.

_____. 1998a. “‘The Human Right to Water’”, Water Policy 1: 487-503.

_____. 1998b. The World’s Water: The Biennial Report on Fresh Water Resources. Washington, D.C. and Covelo, Calif.: Island Press.

Gleick, Peter H., ed. 1993b. Water in Crisis. A Guide to the World’s Fresh Water Resources. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, for Pacific Institute for Studies in Development, Environment and Security and Stockholm Environment Institute.

Hardin, Garrett. 1968. “‘The Tragedy of the Commons’”, Science 162(3859): 1243-1248. Reprinted in Managing the Commons, pp. 16-30, ed. Garrett Hardin and John Baden. New York: Freeman.

Homer-Dixon, Thomas E 1991. “‘On the Threshold: Environmental Changes as Causes of Acute Conflict’”, International Security 16( 2): 76-116. Reprinted in Lynn-Jones and Miller, eds. (43-83).

_____. 1994. “‘Environmental Scarcities and Violent Conflict: Evidence from Cases’”, International Security 19( 1): 5-40. Reprinted in Lynn-Jones and Miller, eds. (144-179).

_____. 1995a. ‘Environmental Scarcity and Intergroup Conflict’, in Michael Klare and Daniel Thomas, World Security: Challenges for the New Century, 2d ed. New York: St. Martin’s (290-313).

_____. 1995b. “‘The Ingenuity Gap: Can Poor Countries Adapt to Resource Scarcity?’”, Population and Development Review 21( 5): 587-612.

_____. 1995c. Strategies for Studying Causation in Complex Ecological Political Systems. Toronto: Project on Environment, Population and Security, University College, University of Toronto and Washington, D.C.: American Association for the Advancement of Science.

_____. 1996. “‘Strategies for Studying Complex Ecological-Political Systems’”, Journal of Environment and Development 5( 2): 132-148.

_____. 1999. Environment, Scarcity, and Violence. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

Homer-Dixon, Thomas F., and Valerie Percival. 1996. Environmental Scarcity and Violent Conflict: Briefing Book. Toronto: Project on Environment, Population.

Klötzli, Stefan. 1997. ‘The “Aral Sea Syndrome” and Regional Cooperation in Central Asia: Opportunity or Obstacle?’, ch. 25 in Gleditsch, ed. 1997b (417-434).

Libiszewski, Stephan. 1992. ‘What Is an Environmental Conflict?’, in Occasional Paper (1). Bern: Swiss Peace Foundation and Zürich: Center for Security Studies and Conflict Research, Swiss Federal Institute of Technology.

_____. 1997. ‘Integrating Political and Technical Approaches: Lessons from the Israeli-Jordanian Water Negotiations’, ch. 23 in Gleditsch, ed., 1997b (385-402).

Levy, Marc A. 1993. ‘European Acid Rain: The Power of Tote-Board Diplomacy’, in Haas, Keohane, and Levy, eds. (75-132).

_____. 1995. “‘Is the Environment a National Security Issue?’”, International Security 20( 2): 35-62.

Lodgaard, Sverre. 1992. “‘Environmental Security, World Order and Environmental Conflict Resolution’”, in Conversion and the Environment, pp. 115-136, ed. Nils Petter Gleditsch. Proceedings of a Seminar in Perm, Russia. PRIO Report (2). Kate and McKinsey.

MacKenzie, Craig. 1994. Degradation of Arable Land Resources: Policy Options and Considerations Within the Context of Rural Restructuring in South Africa. Working Paper 8. Johannesburg: Land and Agriculture Policy Centre.

McCrory John, “Environmental Mediation — Another Piece for the Puzzle.” Vermont Law Review, 6 (1981): 49-84.

Mongabay. 2008. Brazil fines 24 ethanol producers for illegal forest clearing. Web.

Opschoor, Johannes B. 1989. “‘North-South Trade, Resource Degradation and Economic Security’”, Bulletin of Peace Proposals 20( 2): 135-142.

Ray, James L. 1995. Democracy and International Conflict: An Evaluation of the Democratic Peace Proposition. Columbia, S.C.: University of South Carolina Press.

Renner, Michael. 1996. Fighting for Survival Environmental Decline, Social Conflict, and the New Age of Insecurity. New York and London: Norton, for Worldwatch.

_____. 1999. Ending Violent Conflict. Worldwatch Paper (146). Washington, D.C.: Worldwatch.

Renner, Michael, Mario Pianta, and Cinzia Franchi. 1991. ‘International Conflict and Environmental Degradation’, ch. 5 in New Directions in Conflict Theory. Conflict Resolution and Conflict Transformation, pp. 108-128, ed. Raimo Väyrynen. London: Sage, in association with the International Social Science Council.

Russett, Bruce M. 1993. Grasping the Democratic Peace:Principles for a Post-Cold War World. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

Russett, Bruce M., and Harvey Starr. 2000. ‘From Democratic Peace to Kantian Peace: Democracy and Conflict in the International System’, in Handbook of War Studies II, pp. 93-128, ed. Manus I. Midlarsky. Ann Arbor, Mich.: University of Michigan Press.

Whyte, Anne. 1995. Building a New South Africa. Ottawa: International Development Research Centre.