Executive Summary

This report starts by defining knowledge and addressing how knowledge is managed. The report also notes that knowledge management (KM) requires one to possess knowledge; since only then can the information assets that a firm or an individual owns be identified, captured, evaluated, retrieved and shared.

Applied to Maroochy Water Services, a knowledge audit reveals that the water and sewerage service provider purchased the SCADA system without understanding the risks and threats of such a system. In the conclusion, the report notes that the lack of knowledge on Maroochy Water Services part, and the inadequate knowledge management by Hunter Watertech created gaps in knowledge that enabled for an attacker to hack into the SCADA system, causing it to malfunction.

Introduction

This report examines knowledge management in the case of Maroochy Water Services, Australia. The report explores the concept of knowledge and its management, and the application of knowledge management in the subject organisation. The report has a knowledge audit section, which reveals knowledge gaps that led to a successful cyber attack on Maroochy Water Services.

Knowledge and how its managed

Among the simplest definitions of knowledge in literature is offered by Wilson (2002) who states that the term simply refers to what one knows.

This report will however adopt Firestone’s (2013, p.9) definition, which describes knowledge as “the tested, evaluated and surviving structure of information… that is developed by a living system to help itself solve problems and which may help itself to adapt”. From the foregoing definition, it is obvious that knowledge is structured information, which has undergone and survived tests and evaluation, and is hence deemed befitting to help people solve their problems and adapt.

Some analysts argue that knowledge cannot be managed, specifically because, knowledge they claim, is a mindset and not an object (e.g. Wilson 2002). Those who support the idea that knowledge can be managed do so based on the view that knowledge can be manipulated or stored (Zack 1999). However, the ability of a person or an organisation to manipulate or store knowledge, hence manage it, depends on its type.

Tacit knowledge for example is a type of knowledge that is understood and applied subconsciously. As such, it is hard to articulate, store or manipulate it. Explicit knowledge on the other hand is a form of knowledge that is abstract, easily articulated, codified, shared, and documented; hence easily manageable (Zack 1999).

Managing knowledge also depends on its availability and ease of use. Zack (1999) observes that general knowledge for example is publicly available and hence easy to manage, while specific knowledge is context-specific, and as such, it requires more specific management.

Knowledge Management

Knowledge Management (KM) is defined as a concept and a discipline. Davenport (1994 cited by Koenig 2012, p.2) for example defines knowledge management as “the process of capturing, distributing, and effectively using knowledge”. On his part, Duhon (1998 cited by Koenig 2012, p. 4) defines KM as “a discipline that promotes an integrated approach to identifying, capturing, evaluating, retrieving, and sharing all of an enterprise’s information assets”.

The assets mentioned in the foregoing quotation includes such things as documents, procedures, policies, databases, experience and the un-captured expertise of individual employees. This report will adopt Duhon’s (1998 cited by Koenig 2012) definition since it appears to me more inclusive.

The fixation that organisations and scholars have with KM in the past decade is arguably informed by the valuable and strategic nature attached to organisational knowledge. Zack (1999, p. 45) for example observes that “organisations are being advised that to remain competitive, they must efficiently and effectively create, locate, capture, and share their organisation’s knowledge and expertise, and have the ability to bring that knowledge to bear on problems and opportunities”.

Taking such advise into consideration, firms are implementing KM processes, but as Zack (1999) notes, few firms have successfully managed to have foolproof KM architectures. Perhaps the fragmented nature of knowledge – i.e. into tacit, explicit and implicit knowledge – makes it hard for organisations to avoid all the risks posed by KM. The case of Maroochy Water Service is one illustration of the foregoing observation.

Maroochy Water Services

The case study of Maroochy Water Services (hereunder MWS) as indicated by Abrams and Weiss (2000) will be used in this report’s knowledge audit. As its name suggests, MWS is a water service firm, which serves the people of Maroochy Shire Council in Australia through sewage management and the provision of clean water. In 2000, MWS came under attack from a knowledgeable person by the name of Vitek Boden.

Boden had worked for Hunter Watertech-the firm that MWS had contracted to install the Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition (SCADA) system. Boden had apparently quit his job at Hunter Watertech and sought a new job, which he did not get, at Maroochy Shire Council.

In what Abrams and Weiss (2000, p. 1) describe as a decision to “get even with both the Council and his employer”, Boden launched a malicious cyber attack, which caused the sewerage system at MWS to malfunction causing great losses to marine life and a great discomfort to residents.

Boden’s abilities to launch the cyber attack on MWS was pegged on the specific knowledge he had acquired about SCADA while he was still working at Hunter Watertech, and the physical assets – i.e. the radio and computer, which he had stolen from the premises.

The SCADA system is used in monitoring and controlling operation in water distribution systems, sewage treatment plants, gas and oil pipelines and power distribution plants (Slay & Miller 2008). The system gathers real-time data, control processes, and monitor equipment wherever they are installed and properly configured.

Among the first things that MWS noticed was that communication sent to sewage pumping stations by radio links was lost. Pumps would also fail, and the alarms installed for purposes of alerting staff about faults in the system would not serve their intended purpose (Slay & Miller 2008). What investigators in MWS knew about the crisis they were facing included:

- Alarms at the pump stations were not working. They however could not explain the reasons

- There were communication failures resulting from increased radio traffic. The source of the radio traffic could however not be established

- The software used in the pump stations would regularly have some modified configuration settings. It was initially thought that the system did, but this had not been verified

- The pumps would sometime run continually or turn off at an inopportune moment. The reasons for such behaviours by the system however could not be explained

- Whenever the pump lockups occurred, the alarms, which were supposed to alert staff, did not go off. The reason for the alarm failure was again thought to be software-related but no verification had been made Source (Slay & Miller, 2008)

From the above points, it is clear that there were existing knowledge gaps about the functioning of the SCADA system. Specifically, Abrams and Weiss (2000, p. 11) observe that the personnel working at MWS “were not trained in preventing, recognizing, or responding to cyber-related incidents”. In other words, they lacked the knowledge, and as Wilson (2002), one cannot manage knowledge that he/she does not have.

It is clear that MWS purchased the SCADA system from the contractor, but did not develop the internal knowledge capacity to manage the same. The foregoing observation is further reinforced by the fact that an employee from Hunter Watertech was the one who eventually realised that the problems at MWS system were caused by a human actor.

Stakeholder audit

The stakeholders mentioned in the MWS case study are:

- Maroochy Water Services- The user of the SCADA targeted by Boden

- Robert Stringfellow: The civil engineer charged with overseeing operations at MWS when the security breech occurred

- Vitek Boden: a former employee of Hunter Watertech, who possessed explicit knowledge from his employer, which enabled him to hack into the MWS SCADA system

- Hunter Watertech: the contractor who sold and installed the SCADA system (and all the hardware and software) to MWS.

Knowledge Audit

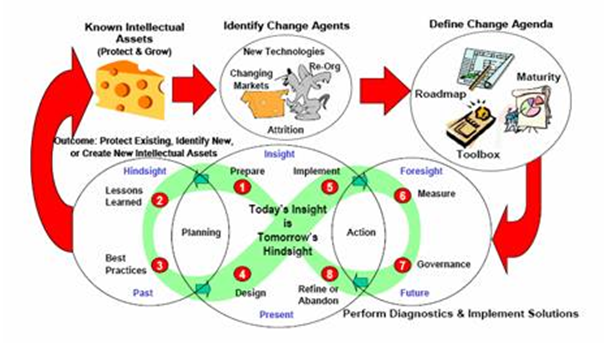

To fully understand the knowledge situation at MWS, the Frid Framework developed by the Canadian Institute of Knowledge Management (CIKM) for purposes of framing knowledge audits will be used. The framework is illustrated in figure 1 below

Figure 1: The Frid framework for knowledge audit

Source: CIKM (cited by Sharma & Chowdhury 2007).

By using the Frid framework above, Sharma and Chowdhury (2007) indicates that one is able to soundly investigate an organisation’s knowledge status by focusing on:

- Existing organisational knowledge needs

- Existing knowledge assets and/or resources and their location

- Existing knowledge gaps

- How knowledge flows in the organisation

- Existing hindrances to the flow of knowledge in the organisation (e.g. people, technology or processes)

- How the organisation creates, shares and re-use knowledge based on benchmarks or best practices

- The knowledge flows that the organisation uses to become a sustainable organisation.

From the above points, the following were identified about MWS:

- The company had identified the need to use SCADA for more effective water and sewerage functions, and had hence purchased the needful hardware, software and installation and maintenance services from Hunter Watertech.

- MWS personnel knew when the SCADA system was not functioning properly

- MWS personnel did not possess the knowledge needed to react fast, or intervene when the system did not function as expected. They also did not have an incident response plan and they were not adequately trained to handle security issues related to the SCADA system.

- MWS relied on the intervention of system analysts from Hunter Watertech

- The flow of knowledge needed to work with the SCADA system was probably hindered by Hunter Watertech, which would have wanted to protect its knowledge against flowing into MWS in a bid to ensure that the former relied on it for managing the system in future.

- There were no existing benchmarks, security or otherwise, relating to SCADA systems at the time that Boden waged his cyber attack on MWS. In other words, neither MWS nor Hunter Watertech possessed the knowledge about possible insider malicious attacks.

- MWS lacked audit policies on the system, which would have mitigated attacks and the effects thereof.

- Communication gaps are also evident in the MWS case study, especially since it would appear that not enough knowledge had been created among MWS employees on how to react if the SCADA system failed

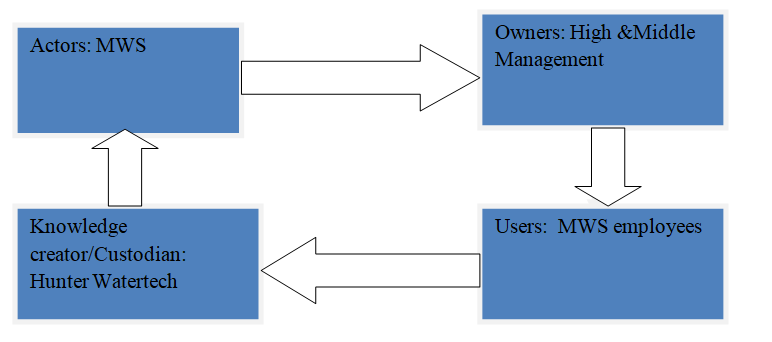

Knowledge Mapping

According to Sharma & Chowdhury (2007), knowledge mapping (K-Mapping) is a “navigation aid to explicit (codified) information and tacit knowledge”. K-mapping helps in linking knowledge creation (and creators) to stores. The K- map below is an illustration of the knowledge asset and resources that MWS has, and where such knowledge can be found – i.e. among holders who include users, connectors, collectors, and knowledge creators

Although it would appear that the incident at MWS was a shared responsibility between the water and sewerage service provider and its contractor Hunter Watertech, the bulk of the responsibility was arguably on MWS. After all, it was its services and processes that malfunctioned resulting in sewage spewing into fresh water sources and killing marine life.

Among the major knowledge gaps appears to be related to the fact that MWS overly relied on the services offered by Hunter Watertech and by so doing, failed to build its own internal knowledge especially in matters related to setting the access and control policies to the SCADA system. MWS also lacked an incident response plan, and this is arguably indicative of the probability that MWS did not seek to understand the threats posed by the new system before purchasing and installing it.

As indicated by Ahmad and Miles (2001), one is only able to manage the knowledge that he/she already has. In MWS’s case, the firm did not possess the knowledge related to the risks of installing the SCADA system, and could not therefore manage the risks when they materialised (Minich & Ragunton 2011).

The absence of audit policies, and the failure by the water services firm to offer security training to its personnel is also indicative that MWS did not possess adequate knowledge needed to securely use the SCADA system.

Notably, knowledge management in MWS scenario was not only related to the firm alone; The contractor who had installed the SCADA systems, and with whom the SCADA devices and program used to hack into the MWS sewage system had been stolen from also had a critical role in the situation. As Bolden’s former employer, Hunter Watertech had the responsibility to ensure that vital knowledge is not carried by or lost to other organisations when employees leave the company.

Bolden was in possession of Hunter Watertech’s explicit knowledge as codified in software, the laptop and the radio devices. His possession of the devices and his vengeful intentions towards his former employer are an indication that Hunter Watertech did not use an effective exit strategy with him as suggested by Houran (2007).

Houran (2007) suggests that all employees who have an intention, or have been forced to leave a company, should ideally pass through a well-structured exit strategy where they get to hand over any kind of explicit knowledge in their possession.

Additionally, the exit strategies, and especially an exit interview, enable the employer to understand any disgruntlement that an employee may have, and make peace with them in order to dissuade any vengeful intentions. It is apparent that Hunter Watertech did not follow any exit strategy hence explaining why their former employee still had a laptop, software and radio devices, which albeit stolen, belonged to the company.

Conclusion

This report has audited knowledge management at MWS in 2000 based on the case study authored by Abrams and Weiss (2000). The audit indicates that MWS did not possess the needful knowledge to securely run the SCADA system, and that the cyber attack by Boden was just an illustration of a lack of adequate knowledge on the firm’s part.

The attack was also an illustration of Hunter Watertech’s inability to manage its knowledge properly especially because the firm lacked an effective exit strategy for its employees. It is because of the absence of an effective exit strategy for employees that Boden was able to carry explicit knowledge from the firm, which he later used in the MWS attack.

Overall however, this report indicates that MWS had a responsibility to acquire and manage knowledge related to the SCADA system before purchasing and installing it for use. The absence of such knowledge culminated in the attack, which has provided valuable lessons for other SCADA system users throughout the world.

References

Abrams, M. & Weiss, J. 2008, Malicious control system cyber security attack case study- Maroochy Water Services, Australia. Web.

Ahmad, K. & Miles, L. A. 2001, ‘Specialist knowledge and its management’, Journal of hydroinformatics, vol. 3, no. 4, pp. 215-229.

Firestone, J. M. 2006, ‘What is knowledge’, In Riskonomics: reducing risk by killing your worst ideas, pp. 1-23. Web.

Houran, J. 2007, ‘the employee exit strategy’, 20-20 Skills, pp. 1-15. Web.

Koenig, M. E. 2012, ‘What is KM? Knowledge management explained’, KM World Magazine. Web.

Minich, C. & Ragunton, H. 2011, Surviving a cyber attack on your SCADA system. Web.

Sharma, R. & Chowdhury, N. 2007, ‘On the use of diagnostic tool for knowledge audits’, Journal of Knowledge Management Practice, vol. 8, no.4.

Slay, J. & Miller, M. 2008, ‘Lessons learned from the Maroochy water breach’, In E Goetz & Shenoi S (eds.), Critical infrastructure protection, Springer, Boston, MA, pp. 73-82.

Wilson, T. D. 2002, ‘The nonsense of ‘knowledge management’, Information Research, vol. 8, no.1. Web.

Zack, O. H. 1999, ‘Managing codified knowledge’, Sloan Management Review, vol. 40, no.4, pp. 45-58.