Introduction and Objectives

Introduction

The only thing constant on earth is ‘change’. The universe as a whole and everything on it undergo transformations with time. The business sector is no exception to the phenomenon of change. For modern day business, Change is an unavoidable reality that comes with both opportunities and challenges. Surviving in this ever-changing business environment saw dramatic changes in the organization- its structure, its approaches and its business functions including marketing, production, finance and investments and others. Particularly, changes in the field of organizational finance, investments and acquisition have been very eye-catching.

During the 1950s-1960s, a new trend emerged wherein a growth aspiring company went for buying another small or medium company with borrowed money thereby using no money or little capital of its own (See, Shleifer & Vishny, 1991). This buying spree with borrowed funds intensified during the 1970-1980s and this time the bigger companies and conglomerates were also involved in such transactions. Purchase or buyout of target companies or divisions of a company using leverage became a very common practice during that period which eventually found recognition as the ‘Leveraged Buyout’ or LBO (CPEE, 2003).

The main idea behind an LBO is that the acquirer purchases the target with a loan collateralized by the target’s own assets. Using target’s assets for securing acquirer’s credit in case of hostile takeover situations brings infamous reputation for LBO (Michelle, 1999).

Any LBO and its outcome has strong bearing on the fortunes of at least three parties involved- the acquirer who goes for the LBO, the company or entity to be taken-over and the shareholders (Cheffins, 2007). Now it is pertinent to know if leveraged buyouts (LBOs) create any value for the acquirer, the target company or business division and the shareholders. There must be some reasons or advantages that drive companies to go for LBOs. A successful LBO is reported to provide a series of benefits to the company initiating it. The company having greater equity stake finds LBO increasing its management commitments and business efforts in effect (See, Zahra, 1999).

Managers and executives can realize substantial financial gains due to overall managerial performance improvements brought about by the LBO (Kaplan, 1997). LBOs can also revitalize a mature company and can improve the market position of a company by increasing company’s capitalization (Carriere G., 2002). Empirical studies indicate that the shareholders of a firm can earn large positive abnormal returns from leveraged buyout and the post-buyout investors can also earn excess returns throughout the buyout completion to initial resale period (Michelle, 1999; Ravenscraft & Scherer, 1989; Jensen & Ruback, 1983).

There exist different potential sources or avenues of value addition in case of leveraged buyout transactions which include- wealth transfers from old public shareholders to the buyout group, wealth transfers from the public bondholders to the investor group, wealth transfers from improved incentives for managerial decision making, and wealth transfers from the government via tax advantages (Lerner, Sorensen & Strombeg, 2008). The new company formed through the LBO is required to support higher levels of debt thereby decreasing taxable income, which, in effect, leads to lower tax payments. Notably, this higher level of debt generates tax interest thereby enhancing the value of the firm (See, Johnson, 2001).

Going for LBO is not the end of struggle for a company, as all LBOs do not guarantee success all the time. There are some potential disadvantages, which a company needs to consider before embarking on the LBO route. Many companies went bankrupt having failed to pay the interests of high debts owing to insufficient cash flow and asset sale (William, 2001). LBO is suicidal for companies which are vulnerable to market competitions and volatility.

The interest rate of LBO debt is very high and paying such high interest rates can damage the credit rating of a company (Fox & Alfred, 1992). High profile corporate leaders have been found to finance takeovers with low quality debt just to earn huge profits by selling off the companies in pieces. This practice has earned bad names and negative publicity for LBOs and soon some critics started arguing that these types of transactions harm the long-term competitiveness of the firms involved.

Once the LBO is done, companies get busy in repaying the debt and thus it may not be possible for the company to spare funds for replacing operating assets and upgrading tools and technologies. This leaves the company to operate with old and outdated systems and tools and many companies even curtail their R&D expenditures under such situation.

This is why critics consider LBO to be an impediment to the growth prospects of a company (Jensen, 1988; Hendershott, 1996). Some argue that LBO transactions have negative impacts on the stakeholders and it leads to job loss due to downsizing of the firm (NBER, 1991). Further, LBOs are also accused to have negative effects on the communities where the company is located (Sirower, 1997).

Thus, there exist divergent views so far as the utility and impacts of leveraged buyouts are concerned. Some finds LBO to be a strategic tool for value addition while others criticize it to be an impediment to future growth and prospects of a company. Knowledge gaps and lack of understanding of the concepts of acquisition and the complexities of different valuation techniques largely contribute to the differences in views about leveraged buyouts. Therefore, it is required to form an unbiased view about the leveraged buyout process and get familiarized with the different valuation techniques. To this effect, this paper conducts a comprehensive review and investigation of the process and techniques of leveraged buyout covering all fronts-theoretical, technical and as well as empirical.

Beginning with this brief background, this chapter goes on to give a preview of the overall research study specifically outlining the research problems, aims and objectives and the methodology of research. The chapter concludes outlining the structure and layout of this report.

Research Problems & Questions

Leveraged buyout, technically and practically, is not as simple as it sounds. The business sector has been conversant with the term ‘leveraged buyout’ or takeover from as early as the 60s & 70s but still not many firms appear to have succeeded in mastering the science and art of the leveraged buyout process. Knowledge gaps with regard to the concepts and valuation techniques of LBO create confusions and doubts culminating to the basic question- do leveraged buyouts create value for the acquirer and the target company?

A quick scan of the available resources on LBO and acquisition reveals few gaps or problem areas and raises some questions requiring thorough investigation. Identified below are some of the major problems and the corresponding research questions which this study seeks to investigate and address.

- LBO is not a sure shot tool for getting success in business. Proactive planning, skills, experience and above all proper knowledge of relevant concepts and techniques are prerequisites for successful execution of LBO. Here the question is- what are the basic concepts, types, advantages and disadvantages of LBO and acquisition initiatives?

- Existing literatures and research works indicate use of wrong valuation techniques and improper application of modeling tools to be the dominant cause of LBO failures. Therefore it is very important to review related literatures and see what are the different valuation techniques and modeling tools used to value target firms and also study how prior research works contribute to the knowledge base of LBO initiatives?

- Prior research works provide empirical evidences on LBO initiatives. Thus, what are the available empirical evidences of LBO?

- All LBOs are not successful. When successful, they create value and when LBOs fail, they even drive a firm to bankruptcy. So, why all LBOs are not successful? How do LBOs create value?

Research Aim & Objectives

The principle aim of this research study is to investigate if leveraged buyouts (LBOs) create any value for the acquirer and the target company. Banking on the research findings and observations, this study attempts to capture some critical success factors for LBO initiatives. On its way to accomplishing this principal aim, this study goes deep into the research subject area to collect and investigate specific facts and figures, which are expected to fill the knowledge gap and address the research questions as pre-identified in Section 1.1. Thus the study objectives are connected to the research problems. Considering the research problems, the following objectives have been identified. The objectives are:

- Conduct a comprehensive review of the available literature on LBO.

- Investigate different valuation techniques, tools and models and explore the contribution of prior research works on LBO.

- Capture and present empirical evidences and hypotheses, if any, pertaining to LBO initiatives.

- Appraise on the value creation potentials of LBO in case of the acquirer and the target company.

Research Methodology & Approach

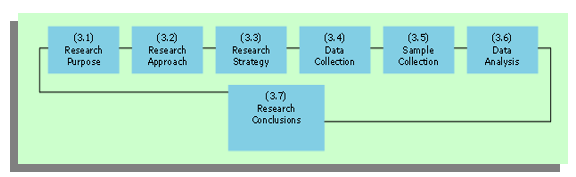

Selecting appropriate methodology is of paramount importance in case of any research study as methodology dictates the quality of study as well the accuracy and reliability of research outputs (See Bryman, 1984). The actual research work undertaken for this study can be broken down into seven inter-dependent sub-tasks as shown in Figure-1.1. Starting with the identification of research purpose, the actual research work proceeds to accomplish other sub-tasks like selection of research strategy, identifying data collection and analysis options, etc. before finishing with the research conclusions.

The principal aim of this research study is to investigate and explore if leveraged buyouts (LBOs) create any value for the acquirer and the target company. Different research options have been scrutinized and finally a research method has been selected, which fits well with the objectives and complexity of the study at hand. With the purpose of conducting an exploratory and descriptive research, a mixed research approach combining both qualitative and quantitative approaches has been adopted here (Ref: Kumar R., 1996).

Going by the objectives of this study, it is required to collect measurable or quantitative data pertaining to project costs, delay periods, etc. as well as non-measurable or qualitative information pertaining to LBO initiatives thereby necessitating adoption of the mixed approach (See, Yin, 1994). The research strategy followed here is dominantly literature based requiring a thorough review and scrutiny of prior research works, earlier case studies and questionnaire surveys. No actual surveys and interviews have been taken up in this case. Complete details of the methodology have been given in Chapter-III of this report.

Conclusion

This chapter presents a preview of the overall research study. Raising the concerns for leveraged buyout and pinpointing the possible knowledge gaps, this chapter presses for conducting a comprehensive review and investigation of LBO initiatives and the valuation techniques and tools. A set of objectives has been identified here carefully considering the depth and gravity of the research problems. The chapter also gives a brief primer to the research methodology. Concluding with the structure and layout of the report, this chapter makes way for taking-up the literature review in the next chapter (Chapter-II).

Literature Review

Introduction

In order to address the research problems and accomplish the objectives as identified in Chapter-I, critical review of available literature and prior arts pertaining to leveraged buyouts is one of the vital components of this study and more so, as this will form the foundation of the research and provide the framework for investigation. Starting with the basic concepts and definitions related to acquisitions and corporate transactions, this chapter goes on to conduct a comprehensive review of the LBO literature presenting the history and theory of leveraged buyout. The chapter concludes discussing and highlighting the contributions of ten published research papers on LBO transactions.

Leveraged Buyout

A leveraged buyout (LBO) can be defined as ‘a transaction in which a group of private investors, typically including management, purchases a significant and controlling equity stake in a public or non-public corporation or a corporate division, using significant debt financing, which it raises by borrowing against the assets and/or cash flows of the target firm taken private’ (Loos Nicholaus, 2005). During the 1950s-1960s, a new trend emerged wherein a growth aspiring company went for buying another small or medium company with borrowed money thereby using no money or little capital of its own (See, Shleifer & Vishny, 1991).

This buying spree with borrowed funds intensified during the 1970-1980s and this time the bigger companies and conglomerates were also involved in such transactions. Purchase or buyout of target companies or divisions of a company using leverage became a very common practice during that period which eventually found recognition as the ‘Leveraged Buyout’ or LBO (CPEE, 2003). The main idea behind an LBO is that the acquirer purchases the target with a loan collateralized by the target’s own assets. Using target’s assets for securing acquirer’s credit in case of hostile takeover situations brings infamous reputation for LBO (Michelle, 1999).

In simple words, LBO is the purchase of a company by using a small investment and a large loan. The new owner would gain control with a small amount of invested capital because he or she is able to secure a large loan for the balance of the amount needed. As Opler & Titman state, leveraged balance sheet has a small portion of equity capital and therefore a large portion of loan capital (Opler & Titman, 1993).

Sometimes it is also called as ‘Highly-Leveraged Transaction (HLT)’ that occurs when a financial sponsor gains control of a majority of a target company’s equity through the use of borrowed money or debt. Generally, the loan capital is borrowed through a combination of prepayable bank facilities and/or public or privately placed bonds, which may be classified as high-yield debt, also called junk bonds. Usually, the acquired company’s balance sheet reflects the debt, which is repaid by the acquired company’s free cash flow (See, Andres et.al., 2003).

Theory of Leveraged Buyouts (LBOs)

When considered in respect of specific capital structure, every leveraged buyout is unique on its own notwithstanding the element of financial leverage, which all LBOs commonly use for acquisition purpose. Under the LBO process, the private equity firm acquiring the target company uses a combination of debt and equity for financing the acquisition (TSB, 2003).

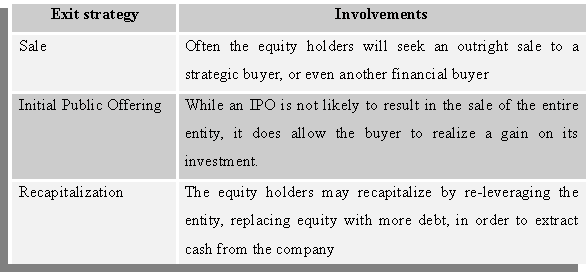

Notably, the assets of the acquired business stand security to a portion of the debt. The business after the acquisition generates cash flows that are used for paying off the debt incurred in its buyout. The debt holders get locked for a fixed return in case of a LBO making way for the equity holders to receive all benefits from any capital gains (Michelle, 1999). This is why financial buyers invest in highly leveraged companies seeking to generate large equity returns. An LBO fund will typically try to realize a return on an LBO within three to five years. There exist aggressive strategies for LBO investment exit, which can be separated into three heads- sale, initial public offering and recapitalization. Table-2.2 above outlines the three LBO investment exit options (TSB, 2003).

LBO- Value Creation

There are various sources or avenues of value creation in case of a leveraged buyout. A range of drivers directly influences operational efficiency and optimal utilization of assets of the company, which are referred to as- direct, intrinsic, operational or value creating drivers. There are another set of drivers as well which are non-operational in nature but contribute to expansion of value created between acquisition and realization of the investment. These are referred to as- indirect, extrinsic, non-operational or value capturing drivers. (See, Baker, 1992; Anslinger & Copeland, 1996).

Direct Drivers of Value Creation

Direct drivers have a direct effect on the free cash flow generation of the company. This cash flow generation is done through increasing revenues, reducing expenses or through efficient use of capital following sophisticated financial engineering practices. Thus, direct drivers enhance financial performance resulting in real value creation (Kitching, 1989).

Indirect Drivers of Value Creation

These are important non-operational drivers in a buyout transaction that also play a vital role in value creation. Being indirect drivers, they do not directly affect performance but they amplify and enhance the positive performance effects brought about by the direct drivers (Butler, 2001).

Thus, the above drivers relate to value creation in the post acquisition period with direct drivers affecting cash flows and indirect drivers enhancing the performance of the direct drivers (DeAngelo et.al., 1988). Apart from the post acquisition period, there remain ample scopes for value creation during the negotiation and acquisition process as well thereby implying that there exist other sources of value creation or value drivers in case of leveraged buyouts. These value drivers either relate to information asymmetries and capital market efficiencies or superior negotiation skills (Loos Nicholaus, 2005).

LBO- Performance Evaluation & Valuation Techniques

One of the most important components of LBO transaction is the financial evaluation and valuation of the target company. Just being a strategically good transaction is not enough unless the transaction is financially good (TSB, 2003). No company will go for a LBO unless it finds the target company advantageous strategically and financially. Financial valuation of the target company provides the base for the acquiring company to judiciously arrive at a ‘buy’ or ‘no-buy’ decision (DeAngelo et.al., 1988).

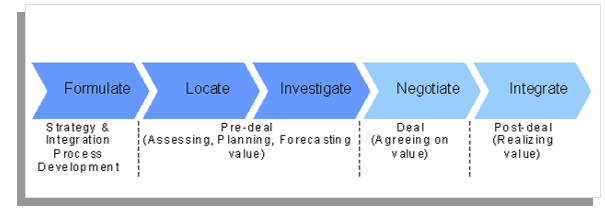

Thus, the significance of financial valuation cannot be doubted but as an activity, it is not as simple as it sounds. There exist different methods and techniques for valuation of a target company whose application requires good understanding of the overall buyout process. The Watson Wyatt Deal Flow Model, as shown in Figure-2.3, provides useful insights into the overall buyout process (See, Brunn Claus, 2007).

The above model can be used to identify where in the process the valuation takes place and consequently help to provide a better justification of the buyout process. The Watson Wyatt Deal Flow Model sub-divides the pre-deal part of the LBO process into four individual phases- formulate, locate, investigate and negotiate. The post-deal part of the process includes the integration phase that identifies the key activities to be done after the deal is signed (Galpin & Herndon, 2000).

The first phase or the formulate-phase requires the company to identify business strategy, set growth strategy, define acquisition criteria and start implementation of the strategy (See, Angwin & Savill, 1997).

Then comes the locate-stage where the company is required to identify and locate a potential target for acquisition. Once the potential target is located, the actual deal making process begins. The major involvements here are- identification of the target markets and companies, target selection, issuing letter of intent and conceiving a M&A plan. This is actually the stage when the company examines the possibility of value creation through the buyout. The third stage or the investigate-stage marks the execution of the initial due diligence process related to the target company. The due diligence needs to consist of financial, operational, legal, environmental, cultural and strategic analyses through which the acquiring company basically improves its understanding and insight of the target company (Galpin & Herndon, 2000).

Setting deal terms and conditions, framing legal obligations, sourcing key talents, finalizing integration terms and closing of the deal are some of the important activities taken-up in this stage. The fifth stage integrate is focused on the implementation and planning of the integration. This phase captures the total outcome of the entire buyout process starting from due diligence to the final and total integration of the two companies.

Total Financial Value

The sum of all equity (E) and debt (D) gives the total financial value of the concerned company, i.e.,

Vl = E + D

where Vl is the total value of the leveraged company and thus the value of a company may also be its signed debt. While taking debt, companies create tax shields calling for tax deduction in lieu of the interest paid on debt. This tax shield is an important aspect of LBO transactions. Now,

Vl = Vu + tcD

Where (Vl) is the value of the leverage company, which is equal to the sum of the value of the un-leavered company (Vu) and the debt tax shield (tcD). This tax shield created by interest qualifies for tax deduction thereby giving the company an opportunity for tax reduction by debt addition, i.e., by increasing its debt. A company’s earnings should be more than its expenditures in order to avoid bankruptcy and remain sustainable. There is a degree of uncertainty in this sustainability issue, which can scare the investors, suppliers and customers away thereby reducing future cash flow in effect. According to Koller et.al. (2005), this is distress or deadweight cost for tracking which, the rate of return on invested capital is the most important value driver for the company (Koller et.al., 2005). Thus,

where (NOPLAT) is the net operating profit less adjusted tax. The above expression gives the company’s ability to make more money than it spends. Therefore, value of an investment is profitable only when it earns a higher return than what is paid in cost of capital.

The literature shows several methods and techniques, which can be applied for making a valuation of a company. The main methods include- Comparable Companies and Comparable Transaction Analysis, Assets Valuation and Discounted Cash Flow (See, Sherman & Hart, 2006). Then there are- Price to Earning, Comparables and Multiples, Adjusted Present Value, Dividends Growth Model, etc. (See, Koller et.al., 2005). It may be noted that no single method can give a complete and correct picture, all can be questioned, and hence it is recommended to apply several valuation methods judiciously.

Price/Earnings (P/E)

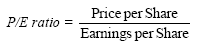

The Price/Earning (P/E) ratio reveals the shareholder’s willingness to pay for a given return. Here the stock price is related to the earnings generated or the future expected earnings. Thus,

When the acquiring company acquires another company both having a lower P/E ratio, there is a rise in the earnings per share of the target company (Weston & Weaver, 2001). Then,

Where (g) stands for expected growth in earnings and cash flow; ® is the rate of return earned on investment and (k) is the rate of discount. According to Ross et.al. (2005), a normal P/E ratio as per empirical evidence is around 30. This P/E is basically a good indicator of how the market values the performance of a company. This ratio can be used as a valuation method provided some inherent limitations are taken care of. In case of a bull market having lots of opportunities, the general valuation and willingness to pay for a higher P/E ratio is normal but this may end up giving a too high value of the company (Ross et.al., 2005). This ratio is fit for use in case of companies listed at a stock market considering the needs for readily available numbers and figures to carryout calculations and comparisons.

Discounted Cash Flow (DCF)

According to Copeland et.al. (1990), this method provides a reliable and detailed insight into the value of the company (Copeland et.al., 1990) and this is why it has become the most trusted and utilized valuation method (See, Weston & Weaver, 2001). The present value of all the future free cashflows (FCF) generated by the company is basically the discounted cashflow (DCF), which can be calculated better by using this method. The calculated FCF when discounted with an estimated Cost of Capital (COC) assures that the cashflow generated is available to the providers of the capital (Copeland et.al., 1990).

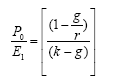

This method accounts for time value of money and relative risk of investment but it is highly sensitive to the discount rate. The major steps under this method include projection of ‘free cash flows to firm’ normally for a period of five years and discounting back at an appropriate discount rate and determination of terminal value using multiples method and perpetuity growth method (See, Hamilton Lin). Forecasting FCF under this method needs different values like the EBITDA (earnings before interest, expense, taxes, depreciation and amortization), Net Income, NOPAT (net operating profits after tax), Cost of Capital (COC), etc. As shown in Watson & Weaver (2001), the total DCF can be calculated by (Weston & Weaver, 2001)-

Where (k) is the cost of capital and (n) is the sequence of years. This leads to the total of all individual future free cashflows (FCFs). The resultant number or value gives an indication as to what the future value of the company is worth and what the present value of the company is.

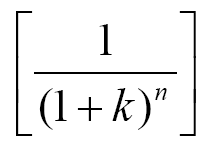

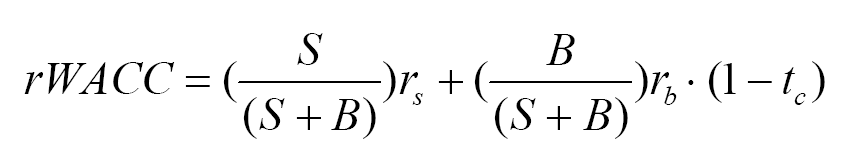

Weighted Average Cost of Capital (WACC)

WACC is basically the discount rate used to discount a series of future values to the present values and selection of this discount rate is very important in case of DCF analysis. WACC calculation requires inputs like- interest rate of debt (cost of debt), interest rate of preferred (cost of preferred), cost of equity estimate, measuring the systematic risk of a security (Beta) and approximated cost of equity (using CAPM, Capital Asset Pricing Model) (See, Hamilton Lin). In case of application of WACC, the company is assumed to be simultaneously financed by both debt and equity and thus, the cost of capital (COC) here is a combination of weighted debt and weighted equity.

According to Koller et.al. (2005), WACC is the time value of money used to discount expected future cashflows (CFs) to the present value and besides being reliable, it is quite a simple valuation method (Koller et.al., 2005). The relationship between debt and equity changes with the changes in financing over time and naturally WACC does the same. This implies that the WACC has to be adjusted and recalculated every time there is a change in the financing of the company (See, Ross et al. 2005; Koller et al 2005). The formula to calculate WACC after tax is-

Where (S) is equity, (B) is debt and (tc) is tax rate.

Adjusted Present Value (APV)

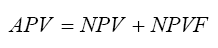

In case of the changing capital structure, APV is the best alternative to the WACC, which values the cash flow of the capital structure (tax shield) separate from the capital structure (Ross et.al., 2005). Thus, the APV method can be represented separating the operation into two components as below-

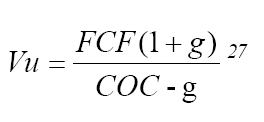

The value (APV) of a project of the leveraged firm is equal to the summation of the value of the project of an un-levered firm (NPV) and the net present value of the finance side effects (NPVF). The side effects may include- the tax subsidy to debt, cost of new debt issue, the cost of financial distress and subsidies to debt financing (Koller et.al., 2005). According to Damodaran (2002), in case of the APV method, the valuation takes place in three steps (Damodaran, 2002). Estimated first is the value of an un-levered company, company having no debt i.e., it’s a total equity financed company. The formula is-

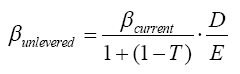

Where (Vu) is the total value of the un-levered company and (g) is the expected growth rate. The un-levered cost of equity that is similar to the cost of capital (COC) needs to be estimated here and for this, the systematic risk (β) has to be calculated using-

Where βunlevered is the un-levered beta and βcurrent is the current equity beta of the company; T is the tax for the firm and D/E is the current debt to equity ratio of the firm.

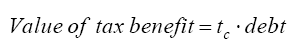

The second step involves calculation of the expected tax shield considering tax savings as perpetuity following-

Where (tc) is the marginal tax rate, which is assumed to be constant in time.

The last step deals with the estimation of the expected bankruptcy cost and the effects. The present value of bankruptcy is calculated as the probability of bankruptcy times the cost of bankruptcy. This step requires good judgment and qualified guesses for the bankruptcy factors (Ross et.al., 2005).

Valuation Techniques- Advantages & Disadvantages

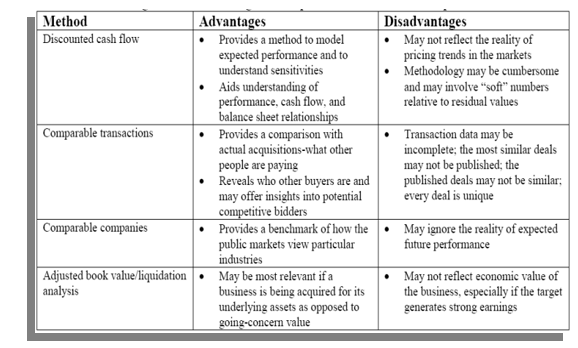

There are different valuation methods and techniques all of which have advantages and disadvantages of their own as listed in Table-2.4 below.

As mentioned earlier, no single valuation is sufficient and 100% accurate. Out of the different valuation methods, some are somehow better then the rest but again, selection of methods, proper application, availability and reliability of the required inputs are prerequisites to successful buyout valuation.

Previous Studies on LBO- Contributions & Evidences

As mentioned earlier, LBO is not a new phenomenon for the business and academic communities. Our first acquaintance with LBO dates back to the 1960-1970s however it gained popularity only during the 1980-1990s when the business sector went on to adopt the LBO route realizing the strategic utility and value addition potentials of the leveraged buyout process. Today, LBO is considered to be a strategic asset for a modern organization.

Paper – I: “Accounting Numbers as Market Valuation Substitutes”

Paper-I is a study carried out by DeAngelo Linda Elizabeth titled ‘ Accounting Numbers as Market Valuation Substitutes: A Study of Management Buyouts of Public Stockholders’. This has been a very well recognized and extensively referred research work since its publication in 1986. The early 1980s actually mark the second phase of LBO introduction in the business sector when the leveraged buyout process came under the scanner facing severe criticisms and negative vibes from all stakeholders, especially from the public stockholders. The public stockholders then claimed that the management buyout process unjustifiably favors the insider managers thereby victimizing them in the process.

Highlighting the severe conflicts between them and the insider managers, the public stockholders alleged that the leveraged buyout practices provide scopes for the managers to manipulate incomes or earnings thereby reducing the final buyout compensation in effect. In case of management buyouts, the insider-managers play the twin roles of business negotiator and share purchaser consequently having total control in both the initiation and finalization stages of the buyout transaction or deal. The manager first negotiates the fare value for the publicly held shares and then he goes on to purchase the same shares at a suitable price or buyout compensation.

This means, the manager is both the seller and the purchaser of the publicly held shares on sale. The fair value of the common shares is arrived at based on the financial details of the company the manager provides.

Therefore, the manager can manipulate and alter company’s financial details in such a way that the resultant share compensation or the final buyout value gets reduced to his advantage (Longstreth, 1983).

This study of DeAngelo provides practical insights on LBO transactions and addresses the above question. A total of 64 firms listed in the New York and American Stock Exchange have been selected for this study. All the selected firms were involved in management buyout of public stockholders during 1973-1982. The available theoretical knowledge indicates the possibility of income manipulation by the insider managers and confirms the existence of a conflict between the managers and the stockholders. However, DeAngelo’s empirical analysis does not support the above hypothetical conclusions that managers systematically understate earnings prior to actual management buyout and that this understatement is exposed by the systematic reduction in the total accruals.

The findings of this study are not in line with the findings of other studies like Healy (1983) who found evidence of income manipulation by the insider managers (Healy, 1983). However, these findings match with those of Liberty & Zimmerman (1985) who found no indication about systematic manipulation of earnings by the managers (Liberty & Zimmerman, 1985). Finally this study concludes that the managers did not indulge in any income manipulation because they knew that the financial statements of the LBO might come under severe scrutiny and examination by the stockholders. In this case, the managers did not tamper with the income figures fearing the consequences of being caught during scrutiny of the financial statements.

Paper – II: “Beatrice: A Study in the Creation and Destruction of Value”

‘Beatrice: A Study in the Creation and Destruction of Value’ is another important work initiated by George P. Baker in the year 1992. Here, Baker scans through the history of Beatrice, a small company founded in 1891, tracks its unprecedented growth and diversification brought about by strategic acquisitions and finally, takes stock of the leveraged buyout and sell-off initiatives of the company. Beatrice was more than 100 years old company which, starting as a small creamery, went on to become a diversified consumer and industrial products firm (Baker, 1992). This company was touted to be amongst the five best-managed companies in America.

Beatrice mastered huge growth and value enhancement through strategic acquisitions and it had flourishing business until the late 1970s. However, afterward it found itself entangled in some strategic and internal governance related problems causing substantial loss or erosion of value. Continuous erosion of value compelled Beatrice to go for financial restructuring and finally in 1986, it was taken-over by Kohlberg, Kravis and Roberts (KKR) through a leveraged buyout leading to the sale of all its assets with in the next four years. The company was involved in 400 acquisitions, 90 divestitures, 1 hostile takeover and sold over 40 units in divisional LBOs.

Thus, Beatrice had gone through many ups and downs. Different CEOs operating at different times adopted different strategies. Some succeeded in creating value for the firm while others failed. Taking on from here, Baker sought to identify the sources of value creation and the reasons for value erosion or destruction. Throughout its existence, the company exhibited exemplary corporate strategy and governance, organizational structures, organizational control and unique acquisition and divestiture decisions. Backer further contributed by analyzing the value consequences of the acquisition and divestiture initiatives of the company and providing insights on the issues, value impacts and the links between different corporate strategies, governance options, organizational structures and controls.

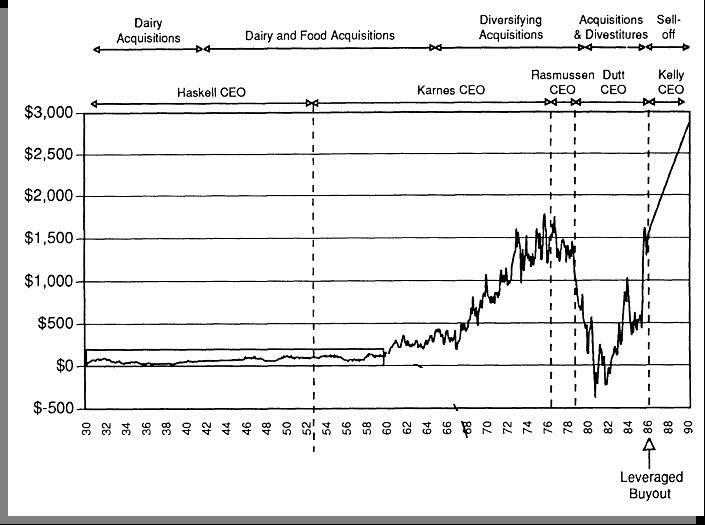

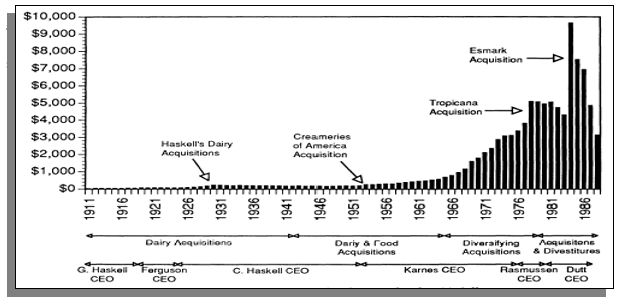

Figure-2.4 above shows the cumulative abnormal returns for Beatrice for the period 1930 to 1990. It also shows the acquisition, diversification, divestment and sell-off initiatives the company was involved in along with the tenures of different CEOs under whose control such initiatives were taken up. The figure clearly indicates that the major initiatives that created good value for the company were the acquisitions of the 1950s to 1970s followed by the divestures and the LBO taken-up later on. This study provides some important lessons and clarifies many issues pertaining to mergers and acquisitions.

The initial acquisition of dairy business was Beatrice’s response to the changing business environment and the company achieved phenomenal success by deriving economies of scale. This success testifies that consolidation is an economically viable and efficient strategy. The study also highlights the value of unrelated acquisitions. Beatrice also acquired foods, confectionaries, polymers and other sectors and continued with its geographical expansions.

This strategy also contributed to the success of Beatrice and provided good returns to its investors. Here Becker found that the success of Beatrice’s diversification strategy was aided by the organizational structure and systems of the company. The company’s success up to the early 1970s proves the utility of decentralized operation requiring least interference from the Headquarters.

However, flawed strategy saw the company loosing its value during the late 1970s and early 1980s. Centralized control policy adopted by Rasmussen and Dutt lead to destruction of value consequently pushing the company to fall prey to hostile corporate control activity in the capital market. Thus, this study highlights the importance of organizational structure and governance in value creation. The success of Beatrice can be attributed to the good organizational structure and governance policy adopted by the company and its failure was also an outcome of bad or inappropriate structure and governance policy.

Paper – III: “Controlling the conflicts of interest in Management Buyouts”

This is a study on ‘Controlling the conflicts of interest in Management Buyouts’ by Easterwood et.al.. This study investigates the controversies and the conflicts of interest that arise in case of management buyout where the manager bids to acquire the firm, which he manages. Such transactions were quite common during the 1980s when many firms went for converting their public stock ownerships to private ownerships. In such cases, the managers preferred to play the twin roles of managing the company as well as bidding and acquiring the company through buyout. (Easterwood et.al., 1994).

Participation of the management in the buyout bid leads to conflicts of interest. Here, the fiduciary duty of the manager demands him to go for the highest possible price from a buyout whereas his role as the acquirer or purchaser demands him to go for the lowest possible buyout price in his self-interest. Thus, managers face a dilemma in case of management buyouts owing to the inherent conflicts of interest thereby making it tough to decide on the buyout price, which is economically most suitable and beneficial for the managers. Thus, controlling managerial conflicts of interest is a very important issue in case of a management buyout and this happens to be the focal point of this study. Easterwood et.al. sought to investigate the roles and links of institutional and market factors in minimizing managerial conflicts of interest. They investigated as many as 184 management buyouts to arrive at these three important points-

- pre-buyout shareholders’ returns are grater when managers bid against outside acquirers;

- competition induced bid revisions stand higher compared to shareholders’ litigation induced revisions; and

- incidence of competition is negatively related to the pre-buyout share holdings of the managers.

This paper mainly contributes by examining the role of alternative mechanisms to control the price of management buyouts. Examining the abnormal returns of the management buyouts, the authors concluded that the pre-buyout stockholders earn larger abnormal returns in contested buyouts compared to the buyouts facing no competitions or hostile bids. They also found that after the announcement of explicit competitive bids, revisions are quite larger than shareholder litigation or negotiation associated revisions. Incidence of explicit competition gets reduced in case of large managerial holdings and this reduction in explicit competition leads to reduction in overall return to pre-buyout stockholders.

This means, large managerial holdings imply lower abnormal returns whereas small holdings imply higher abnormal returns. Thus, this study contributes immensely to our knowledge and understanding of the issues and intricacies of management buyouts. The study drives home the fact that management buyouts with explicit bidding competition generates higher stockholder returns, higher offer revisions and most importantly, may aid in controlling buyout offer prices.

Paper – IV: “Do LBO supermarkets charge more?”

The paper taken-up for review is ‘Do LBO supermarkets charge more? An empirical analysis of the effects of LBOs on supermarket pricing’ by Judith A. Chevalier published in the Journal of Finance (Vol. 50; No.-4) in 1995. This paper investigates the shifts in supermarket prices in local markets brought about by supermarket leveraged buyouts (LBOs). There has been extensive use of leveraged buyouts as a strategic move by most of the firms during the late 1980s drawing the attention of the researchers and financial experts.

There exists substantial volume of literature and empirical research pertaining to LBOs majority of which focused on investigating the effects or impacts of leveraged buyouts on firm’s performances and financial expenditures. For example, Kaplan (1988) investigated the impacts of LBOs on the operating performance of the firm (Kaplan, 1989), effects on firm’s capital expenditures evaluated by Smith (1990) (Smith, 1990), impacts on R&D assessed by Long & Ravenscraft (1993) (Long & Ravenscraft, 1993) and Lichtenberg & Siegel (1990) studied the influence of LBOs on employment and compensation (Lichtenberg & Siegel, 1990).

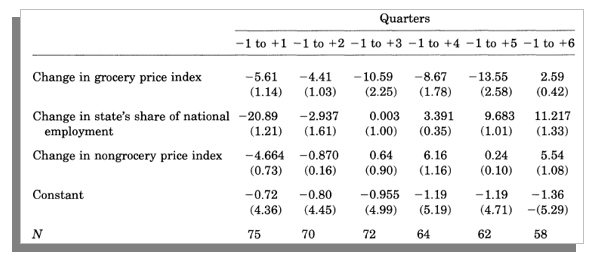

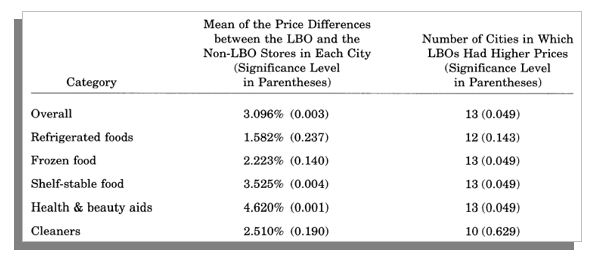

However, this paper is quite different from the above studies considering the fact that Chevalier attempted to investigate and evaluate the impacts of LBOs on the pricing and output behavior of the firm. Using the supermarket industry data at both the local and firm levels, Chevalier carried out this important study the findings of which contribute to our understanding on how LBOs affect the pricing behavior of the firms and their rivals. Focusing on a single industry in a cross-section of the local markets, Chevalier provides insights on the affects of LBOs on the pricing in different markets having different competitive characteristics. This is very crucial for the understanding of the behavior of LBO firms.

The evidences and the findings of this study confirm that the price increases in local markets executing supermarket LBOs when the rival firms in the market are also highly leveraged. This observation indicates that LBOs create the avenues and provide incentives to raise prices. Chevalier’s investigations also reveal that price decreases following LBOs in local markets when the rival firms are not highly leveraged and when a single firm holds large share of the local market. This fall in price can be linked with LBO firms exiting the local market thereby indicating that rival firms attempt to kill the LBO firms.

The findings of this study appear to be consistent with the earlier findings (See, Phillips, 1995). Thus, chevalier’s findings support the hypothesis that there is a linkage between firm capital structure and product market competition. The study also highlights the possible predation motives of the rival firms. Finally, the paper concludes that non-LBO supermarket chains charge inefficiently low prices and despite the benefits, leveraged buyouts are costly to the firms engaged in product market competition leading to suboptimal market investments.

To sum up, this study contributes to extend our knowledge on leveraged buyouts particularly providing evidence-based insights on these three points- impacts of LBOs on product market behavior, possible occurrence of predation and empirical proof of the linkages between capital structure and product market.

Paper- V: “Equity Valuation and Corporate Control”

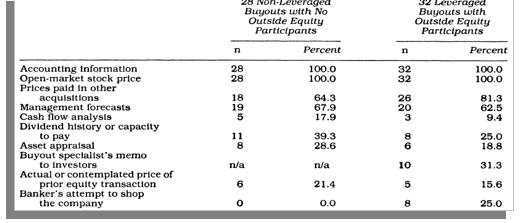

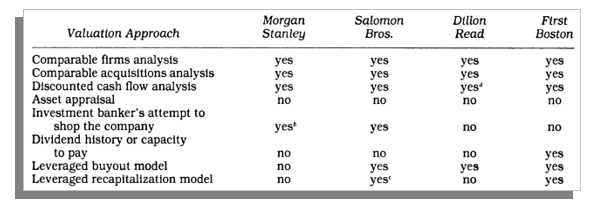

Here we take stock of DeAngelo’s work on ‘Equity Valuation and Corporate Control’ carried out during 1989-90. Considering that there exist substantial differences between open-market stock prices and equity exchange values, the author went on to investigate equity valuation in case of corporate control transactions (DeAngelo, 1989). Like Paper-III, this paper also dives deep into the manager-stockholder conflicts usually engendered in transactions having corporate control. Initiatives like management buyouts and hostile takeovers breed severe conflicts between the managers and the stockholders, which in turn call for independent assessments of equity values by the investment bankers.

This paper contributes to our knowledge on manager-stockholder conflicts resolution and equity valuation. To this end, DeAngelo’s work provides evidence on the valuation information used by investment bankers to evaluate the fairness of a large sample of management buyouts along with scrutinizing their valuation techniques via a detailed case study of working papers on valuation particularly contributed by the investment bankers. Finally, the paper establishes the fact that this demand for accounting information in equity valuation is distinct from that previously recognized in the capital markets or contracting literatures.

This paper presents evidences and insights on the accounting and valuation process of MBOs and also proves the hypothesis on stockholder wealth. Here, it has been confirmed through evidence that accounting information influences the valuation process for management buyouts (MBOs). This in-turn proves the hypothesis that accounting information affects real resource allocation and hence the stockholder wealth. Our impression on accounting information we previously gathered from the capital markets and contracting literatures stands altered following the findings of this study indicating that it plays a more significant and extensive role in controlling manager-stockholder relations in case of MBOs.

Here, the role of accounting information extends beyond just managerial wage, debt contracts and political process as identified by Watts & Zimmerman (1986) (See, Watts & Zimmerman, 1986). Accounting information requirement in case of equity valuation serves different purpose conceptually, which is broader than just restricting attention to open-market stock prices as evident in the capital markets literature.

Paper- VI: “Management Buyout Proposals and Inside Information”

The paper considered for review is Scott D. Lee’s work on ‘Management Buyout Proposals and Inside Information’ published in the Journal of Finance (Vo. XLVII) in 1992. In case of a management buyout, some investors along with some incumbent managers join hands to buy all the outstanding common stock eventually transforming the firm into a private entity. In this case a manager plays the dual roles of a regular manager as well as the buyer or purchaser and this situation leads to criticisms and conflicts of interest as we have seen in case of Paper-III (Section-2.5.3) (See, Easterwood et.al., 1994).

The manager being a key position of a company is expected to have access to important internal information about the company. This information advantage again sparks off criticism alleging that managers use company’s internal information for framing and scheduling buyout proposals to their advantage.

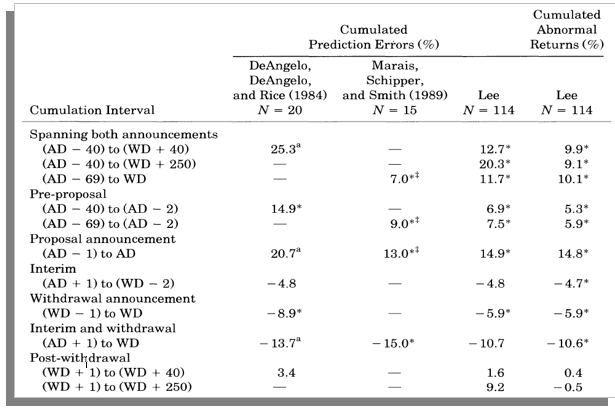

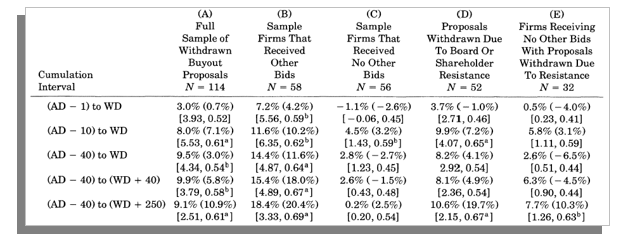

Scott (1992) attempted to investigate the influence of internal information on the management buyout proposals. Taking note of and expanding on DeAngelo & Rice’s work on information impact in buyout proposals, the author selected 118 withdrawn management buyout proposals to explore and examine the shifts in their stock pricees just before the actual buyout proposal announcement and after the buyout withdrawal announcement (Scott, 1992).

This examination of stock price behaviour has been carried out to see if the managers actually have any information about the value of the firm particularly when they propose a buyout. The intention was to figure out if the proposal announcements made by the managers expose any information which is unrelated to the efficiency gains associated with completed buyouts. Further, the author went on to propose and test two hypotheses- the control transfer hypothesis and information hypothesis.

The findings of this study are consistent with that of DeAngelo & Rice (1984). The study contributes to the fact that average cumulative abnormal returns are positive and well pronounced during both buyout proposal and withdrawal announcement periods for firms having already exercised buyout withdrawals. Further, it unearths one important rider specifying that positive returns are attributable to only such firms, which receive other acquisition bids. In case of firms receiving no other acquisition bids, the average cumulative abnormal returns are indistinguishable from zero. Scott (1992) has also highlighted the fact that the reasons for buyout withdrawal as stated by the managers influence the average abnormal returns.

It has been indicated that managers withdrawing buyout proposals and managers completing buyouts. The findings indicate the possibility of manager’s inside information motivating buyout proposals. Interestingly, the findings of this study do not support the information hypothesis. There are no concrete indications about leakage of inside information pertaining to firm value. Finally, the paper concludes that manager’s buyout proposal may not necessarily be motivated by inside information about firm’s value.

Paper- VII: “Management Buyouts: Evidence on Taxes as a Source of Value”

This paper is ‘Management Buyouts: Evidence on Taxes as a Source of Value’ by Steven Kaplan, published in The Journal of Finance, Vol. 44, No. 3, December 28-30, 1989. This is another very extensively referred piece of work whose significance lies in its contribution proving that tax benefits are an important source of the wealth gains in case of management buyouts (Kaplan, 1989). In a MBO, a premium more than 40% above the prevailing market price is paid by the buyout investors to the pre-buyout shareholders in order to take the company private (See, DeAngelo & Rice, 1984). Here, Kaplan sought to highlight the importance of tax benefits by exploring the links between tax benefits and premiums or wealth gains.

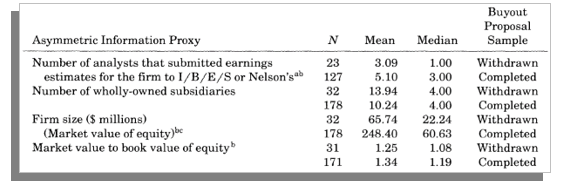

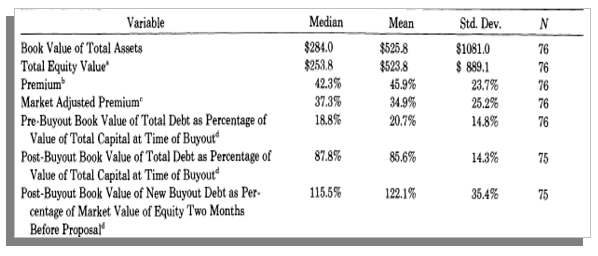

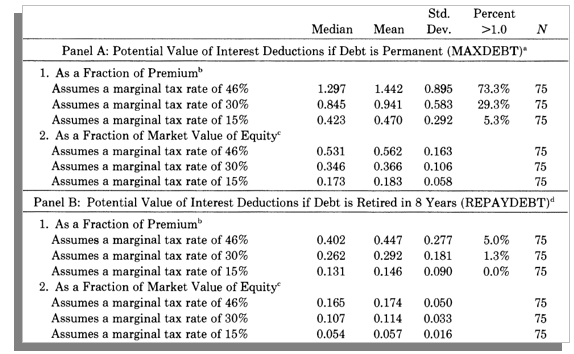

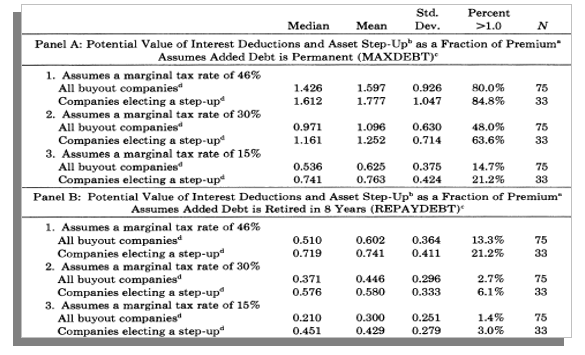

His study concentrated on 76 management buyouts of publicly owned companies completed during 1980 to 1986. Two sources of tax benefits have been scrutinized here- tax benefits from large interest deductions due to large debt for financing MBO and benefits due to increase in tax basis of assets from historical basis to the combined value of purchased equity and the firm’s outstanding liabilities.

The findings of this study support the hypothesis that tax benefits are an important source of wealth gains in management buyout transactions (Kaplan, 1989). Combined tax benefits from increased interest and depreciation deductions have been estimated using data provided to the public shareholders at the time of the buyout. The median value of tax benefits for the sample of 76 MBOs based on the measure used varies from a lower bound estimate of 21.0% to an upper bound estimate of 142.6% of the premium paid to the pre-buyout shareholders. Evaluation of the actual post-buyout tax and debt repayment of the sample companies finds actual debt repayment pattern to be matching in keeping with the relatively high debt levels and eventually the companies paid no federal taxes in the first two years.

Notably, most of the buyout companies do not have tax loss carry-forwards. The speed of debt repayment and the strong relationship between total tax deductions and the premium paid amply indicate that tax benefit is important source of wealth gains in management buyouts. Kaplan also calculated the capital gains tax for the sample companies using the provisions of the tax law applicable during that period. His calculations found the sample to have a median value of about 15% of the premium paid to pre-buyout shareholders indicating that a portion of the buyout tax benefits are used up to counter the cost of the capital gains tax.

Finally, the net effect of management buyouts on tax revenues of the US was calculated taking into account this cost of the capital gains tax and other required parameters. Considering the Tax Reforms Act (TRA) 1986, the maximum corporate rate stands changed from 46% to 34% thereby lowering the maximum tax benefit of interest deductions from 46% to 34%. Importantly, any changes in the TRA do not necessarily reduce the lower bound estimates based on a marginal tax advantage of 15%, the median value used in this paper.

Kaplan concludes that the effective elimination of the step-up basis ability will reduce the tax benefits in case of some transactions and may even reduce the premium paid to the prebuyout shareholders. Thus, tax advantages were always there in case of management buyouts however, this advantage decreased marginally under the TRA of 1986. In any case, this will not put an end to buyout activities.

Paper- VIII: “Management buyouts of divisions and shareholder wealth”

The paper considered here is ‘Management buyouts of divisions and shareholder wealth’ by Hite G.L. & Vetsuypens M.R. published in The Journal of Finance in 1989. This paper investigates the influence of divisional management buyout proposals on the wealth position of the shareholders of the parent company. Actually, the paper investigated the shareholder wealth effects associated with asset sales to corporate insiders (Hite & Vetsuypens, 1989).

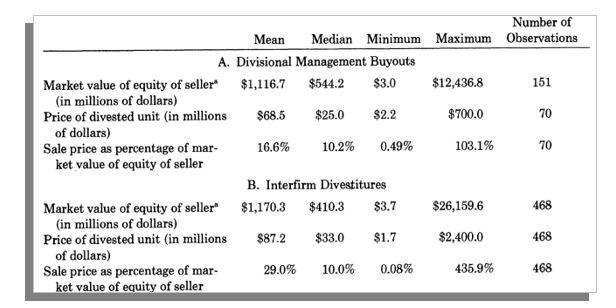

In such transactions, the objectives of the management and the shareholders are quite different. Characteristically, management buyouts of divisions are akin to going-private transactions having no scopes for arm’s length bargaining between the buyer and the seller. The authors scrutinized a sample of 151 management buyouts of divisions to conclude that parent company shareholder, on an average, do not lose from such asset sales.

The study contributes to the evidences that parent company shareholders on an average find abnormal returns of 0.55% during the first couple of days following the announcements of divisional buyouts. Statistically, this return is quite significant while the gains are relatively small. The authors however observed that the gains are not much smaller compared to the average gains of 1.12% as they worked out for a sample of 468 inter-firm divestitures during the same time-period.

The findings prove the hypotheses that like other sell-offs, management buyout of divisions is an efficient option for reallocation of corporate resources to higher valued uses and such transactions facilitate the parent company shareholders to share the benefits expected to be brought about by the change in ownership. The paper also highlighted that management buyouts of divisions lead to the emergence of privately held corporations with new organizational forms, which are capable of competing with the publicly traded corporations. The study confirms the utility of change in ownership structure owing to the productive gains following potential reductions in the costs of decision management and decision control functions within the public corporation. Such gains make the closely held corporation a viable alternative to the public corporation.

Thus, it is clear that divisional buyouts can lower the costs of the decision management function to the parent company managers by reducing the variety and number of decisions to be made. The complexity of the transactions can be reduced through subsidiary buyouts by giving decision-making authority to the acquiring managers under the supervision of the executives of the parent company. The decision control functions also undergo improvements through modifications in incentive compensation.

Paper- IX: “The Determinants of Leveraged Buyout Activity”

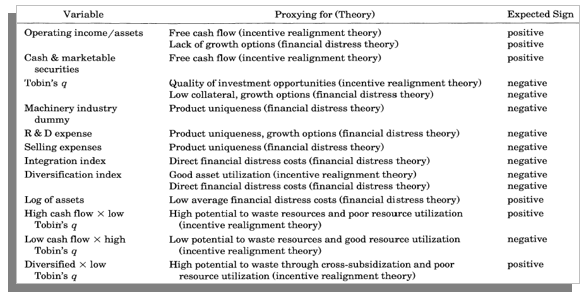

The paper reviewed here is the work of Opler & Titman titled ‘The Determinants of Leveraged Buyout Activity: Free Cash Flow vs. Financial Distress Costs’ published in The Journal of Finance, Vol. XLVIII dated December 1993. The paper contributes to the investigation of the determinants of leveraged buyout (LBO) transactions. The authors went on to compare firms having implemented LBOs and firms having no LBOs in order to identify the determinants of LBO initiatives (See, Opler & Titman, 1993).

Aiming to investigate whether LBOs create wealth or just redistribute wealth, this paper takes on LBO transactions to examine the depth of motivation on account of expected benefits of incentive realignment and the depth of hindrance faced on account of possible financial distress. Opler & Titman sought to test two hypotheses through this study-

- transactions are motivated to create and not just redistribute wealth

- the impact of economic distress on the viability of leveraged buyout firms are overstated.

The authors analyzed variables that facilitated cross-sectional differentiation of the importance of incentive realignment for the LBOs vis-à-vis the importance of the financial distress.

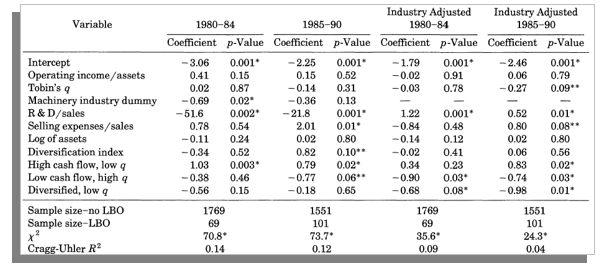

To this end, Tobin’s q and cash flow for LBO and non-LBO firms have been estimated followed by an additional variable, which interacts with the q and cash flow. This actually tests the free cash flow theory of takeovers implying the existence of an important interaction effect between the variables. In contrast, the financial distress cost theory does not imply that the interaction between the two variables is necessarily important. The findings support the fact that firms having high ‘q value’ are better managed and are possibly less prone to the free cash flow problem. Additional variables distinguishing the agency cost theory and the financial distress cost theory considered here are research and development (R&D), expenditures and selling expenses.

The paper as a whole contributes to the stock of knowledge about the free cash flow theory and the financial distress cost theory. The results indicate that free cash flow problems and the financial distress costs are important determinants for firms undertaking LBOs. It is clear that firms having high cash flow and low Tobin’s q are the ones expected to engage in LBO initiatives. This basically proves the free cash flow hypothesis.

The cost of financial distress is generally found to be highest among firms with unique products that may call for future service. Notably, LBO firms have been found to have relatively low R&D expenditures and are never expected to get involved in manufacturing activities and this is inline with the financial distress cost hypothesis. Further, the paper also found LBOs to be more diversified compared to other firms. Stressing on the fact that financial distress costs discourage LBO initiatives, the authors highlighted the importance of debt financing for realizing the gains from going private. It is found that LBO firms use more debts for eliminating taxes. Finally, the paper concludes that debt relates to the incentive problems associated with free cash flow.

Paper- X: “Which takeover targets overinvest?”

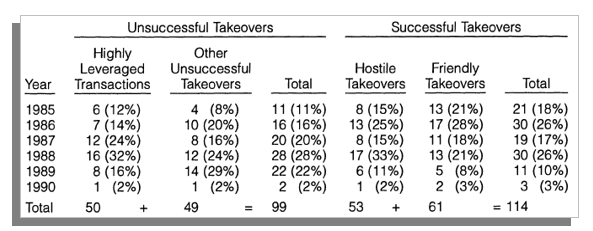

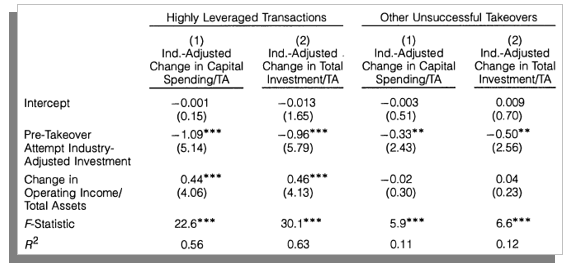

The last paper reviewed here is ‘Which takeover targets overinvest?’ by Hendershott Robert published in the Journal of Financial and Qualitative Analysis, Vol. 31 in the year 1996. This paper contributes to fill the existing gaps in our knowledge pertaining to the overinvestment by the targets successfully acquired through leveraged transactions. The author investigates 213 targets drawn from successfully completed takeovers executed during 1985-1990 and provides evidence as to how the takeovers are biased against considering the overinvestment. Evidences have been found in case of targets using highly leveraged transaction to avoid takeovers. The findings confirm that restructurings mitigate the overinvestment problems of the targets thereby creating value in the process.

Through this study, Hendershott shows that the targets acquired by the bidders in case of successful takeovers cannot have above average free cash flow agency costs just like their bidders (Hendershott, 1996). Firms attempt to reduce their free cash flow by undertaking financial restructuring only when they face disciplinary bids. This restructuring is done in order to avoid the takeover.

Out of the 213 takeover, the highly leveraged transactions (HLTs) were screened for overinvestment. It was observed that prior to HLT, the firms were engaged in capital projects and acquisitions and they spent more in these areas compared to their industry peers. Notably, the firms initiated significant cuts in investment just after the HLTs and these cuts were very much correlated with the earlier industry-adjusted investment of the firms. Further, the target firms were also engaged in cutting down overinvestment as expected. These firms earned abnormal returns following the restructurings, which were again found to be highly correlated with the earlier industry-adjusted investments of the targets. The study also proves that post-HLT underinvestment is not a big problem.

Post-HLT investments of the firms were substantially lesser than their industry peers but they were also found to reduce their leverage and increase investments during the 3rd and 4th years after the HLT. Thus, underinvestment is a temporary phenomenon that can at most remain for four years only. Based on the study results, the author infers that target overinvestment plays an important role in the market for corporate control.

It was also concluded that managers, prior to any takeover threats, are expected to balance the personal cost of using debt in order to preempt any takeover bids. Thus, the free cash flow theory can explain as to why some firms become targets and defeat takeover attempt by restructuring and also explain why other firms never become targets in the first place. However, free cash flow theory cannot explain successful acquisitions very confidently.

Conclusions

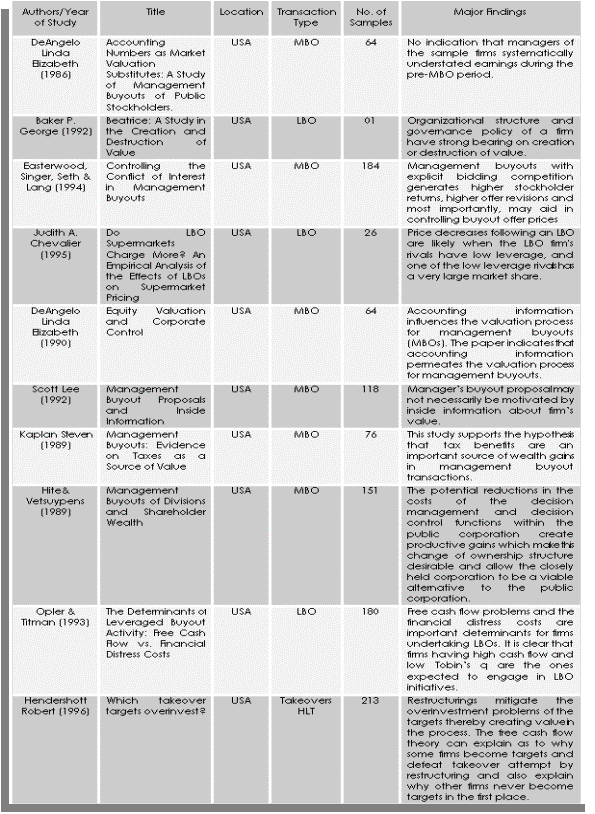

This chapter provides basic understanding about leveraged buyout initiatives running through the history of LBO transactions, transaction structures and LBO theory. Different LBO valuation methods and techniques have been reviewed discerning their merits and demerits. Finally, the chapter presents a thorough scrutiny and review of prior research works pertaining to LBO transactions brief details of which have been compiled in Table-2.5.

Empirical Research and Evidence

Introduction

Leveraged buyout (LBO) transaction is not as easy as it sounds. Going for LBO is not the end of struggle for a company, as all LBOs do not guarantee success all the time. LBO can make or break an organization or business venture. LBO transformed many small companies into big multinational and diversified organization through value addition on one side and on the other it pushed many big companies into bankruptcy and ultimate closure through value erosion. A large body of literature is available on LBO that puts forward related theories, concepts, valuation techniques, hypotheses and other approaches to LBO execution.

Besides theory, success of any LBO initiative depends on various externalities like market situation, manager’s skills, competition levels, geographical location and other practical factors. Thus, studying LBO under real business situation is a must for capturing a holistic view about LBO initiatives. Having reviewed the literature in Chapter-II, necessary theoretical knowledge and insights on research framework have been gathered sufficient for studying and analyzing LBO transaction under the real business set-up. This chapter attempts to conduct empirical analyses and investigations of different LBO transactions actually initiated during 1970s through 2006.

Complete information and data for each and every LBO transactions are not easily available thereby limiting the scope for transaction-by- transaction analysis. The study adopts an alternative approach of analyzing and evaluating ten (10) prior research works specifically related to LBO transactions as listed in Appendix-A. Besides discerning the findings and contributions of each of the papers, some emerging hypotheses have also been highlighted in this chapter. The following sections present the empirical investigations of each of the ten (10) prior-research works.

Empirical Analysis- Paper-I

In this study, DeAngelo investigates accounting decisions made by the managers of some firms listed in the New York and American Stock Exchanges. He initially selects 64 firms from ‘The Wall Street Journal’, which proposed management buyouts of public stockholders during the period 1973-1982. All the 64 proposals represent serious buyout endeavors resulting in a proxy statement that describes the acquisitions. At the time of the initial proposal, out of the 64 firms, 26 were listed in the New York Stock Exchange and 38 were listed in the American Stock Exchange. Further, out of the 64 proposals, 33 were for third-party leveraged buyouts and the remaining 31 had the incumbent management as the equity-holders.

Table-3.1 outlines the descriptive statistics for 64 management buyout proposals during 1973-1982. As shown in the table, the firms going private had a total asset of 212.74 8 million with the median firm having a total asset base of $70.825 million, much lesser than the mean value. The average sample firm had total revenues of 262.093 million with a median of $87.266 million. Also, the managers of the average sample firm owned 36.9% with a median of 36.3% of the firm’s common stock at the time of proposing the buyout.

At the time of buyout initiation, managers of 23 firms out of 64 held majority control while they held 37% of the common stock in the average sample firm. Before the public announcement of the buyout, the market value of the publicly-held common stock based on last day closing share price was $53.8 million for the average firms with a median of $11.153 million. Pre-buyout period saw the average sample firm’s common stock trading below the book value with a market-to-book ratio of 0.937 having a median of 0.730.

However, in case of financial leverage, the debt-to-asset ratio was 0.181 with a median of 0.145. As many as managers of 58 of the 64 proposals (90.6%) offered cash compensation for the public shares. The table also indicates that the final offer price to final annual earnings per share (P/E ratio) of 10.5 with a median of 10.4. The sample average P/E ratio roughly represents the effect of earning change on total buyout compensation considering fair value estimation by capitalization models.

The investment bankers and courts actually consider this P/E ratio as the average rate for earnings valuation. Considering this, managers with a P/E multiple of ten and having 37% of the common stock could avoid some $6.3 million in additional compensation. Thus, due to the PE multiplier, any understatement by the managers could have substantial impact on total buyout compensation. Managers have incentives for understating earnings and lower the buyout compensation but, the fear of external scrutiny and monitoring of their accounting decisions may stop them from doing this.

Hypothesis

“Managers who propose to take a public corporation private systematically understate reported earnings in periods before the acquisition”.

In case of LBO transactions involving managers, there may be some incentives for the managers to follow the accrual approach to LBO valuation. This accrual approach is very advantageous considering the fact that it can potentially reveal the subtle income-reducing techniques adopted by the managers. This approach is less subject to detection by the outsiders and hence managers resort to such techniques and approaches.

In general, any accruals like the accounting accruals reflect the decisions of the managers to write down assets, to recognize or defer revenues, and to capitalize or expense certain costs, such as repair expenditures. Moreover, such accruals also capture the effect of accounting estimates, changes in those estimates, and changes in accounting methods. Interestingly, any accrual as a whole contains both a discretionary and a nondiscretionary component. Syrnbolically, the total accrual in a given period t= 1, AC,, consists of a discretionary accrual, DA,, and a nondiscretionary accrual, NA I.

The empirical evidence presented in this paper, however, does not support the joint hypothesis that managers of sample firms systematically understated earnings before the management buyout, and that such understatement is appropriately measured by a systematic reduction in total accruals.

Empirical Research- Paper-II

Paper-II is the study by Baker (1992) that pertains to rise and fall of a well-known US company named Beatrice. Beatrice was more than 100 years old company which, starting as a small creamery, went on to become a diversified consumer and industrial products firm (Baker, 1992). This company was touted to be amongst the five best-managed companies in America. However, afterward it found itself entangled in some strategic and internal governance related problems causing substantial loss or erosion of value that compelled Beatrice to go for financial restructuring and finally in 1986.

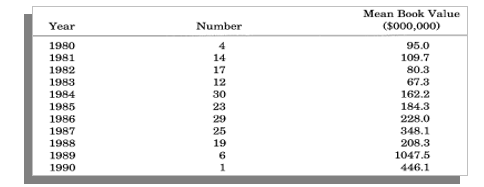

The company grew from a small local creamery to a national company during the era 1890-1939. During the period 1940-1976, Beatrice went for diversification into non-dairy related products like foods, confectionaries, food service equipments and groceries. Following accelerated diversification, the company managed book value of assets of $66.7 million as shown in Figure-3.1.

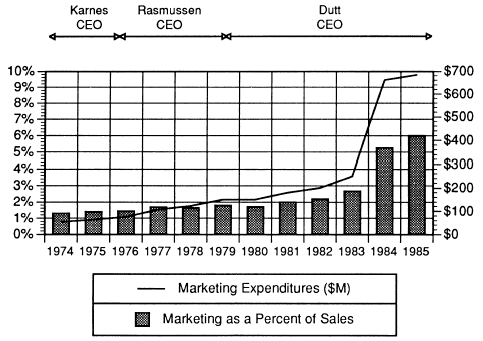

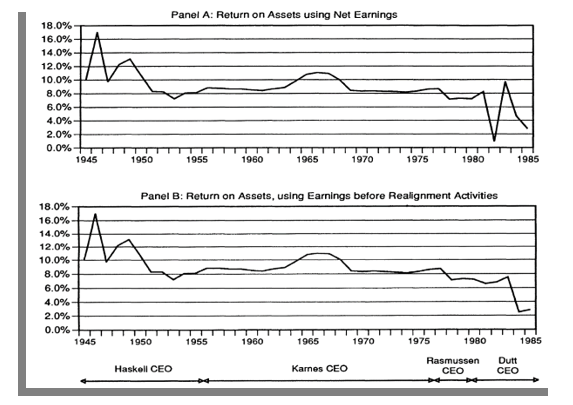

Karnes was the president and CEO of the company during this period when sales increased from $235 million in 1952 to $5.6 billion in 1976 and the total return to the shareholders was over 14% per year and the market also reacted favorably. 1977- 1986 marks the era of beginning of the end for Beatrice. Rasmussen and James Dutt were the two CEOs who operated during this period. Rasmussen preferred big acquisitions and increased marketing expenditures as shown in Figure-3.2.

James Dutt took over in July 1979 from Rasmussen who later abandoned the decentralization policy. During the tenure of Rasmussen and Dutt, the company lost almost $2 billion of market value (Figure-3.3) and its price earnings also declined (Figure-3.4).

The period 1986-1990 marks the leveraged buyout and divestiture initiatives of the firm. Beatrice was involved in the then largest buyout following a bid from KKR and Kelly offering $50 per share. This bid interestingly helped the company to recapture the value it lost under Rasmussen and Dutt. The sources of the funds for the purchase, and the ownership fractions, which resulted following the Beatrice LBO are listed in Table-3.2.

Once the LBO was through, Kelly promptly restored the decentralized organizational structure that Beatrice had earlier. He further reduced headquarters staff by 70% and streamlined all operations. One interesting observation here is that both Karnes and Kelly succeeded in creating value for the company. Karnes generated value through acquisitions whereas Kelly created value by divesting theme after 25 years.

Hypothesis

“Misunderstanding of the effects of conglomeration on the part of the capital market leads to increase in market value of acquired assets”

This value generation by divesting the same assets acquired 25 years ago leads to the hypothesis that “ misunderstanding of the effects of conglomeration on the part of the capital market leads to increase in market value of acquired assets”. This in-turn implies that the investors during the 1960s and 1970s were deceived and bluffed to accept the words of the managers and management theorists who falsely claimed that the asset would generate more worth follow the synergistic effects of centralized decision-making and capital allocation.

Any claim for such a synergy lacks merits and has no management foundation as such claims undermine the importance of detailed understanding of business operations thereby missing to predict that organization whose central management holds excessive decision rights and takes value diminishing decisions are destined to fail. In 1977 the market recognized the weakness of the conglomerate strategy thereby discounting Beatrice’s stock heavily. This discount resulted in substantial loss of value of Beatrice in 1979-1981 and also raised the stock as before when the firm changed direction in the 1980s.

Empirical Analysis- Paper-III

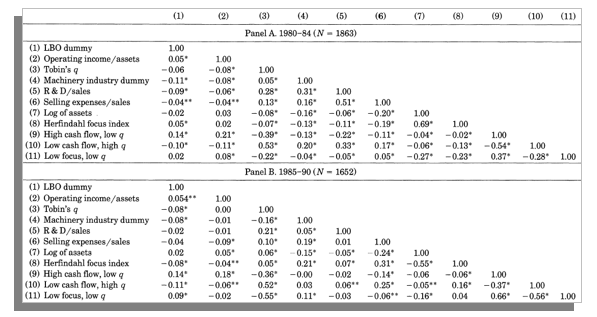

This study investigates the controversies and the conflicts of interest that arise in case of management buyout where the manager bids to acquire the firm, which he manages. The authors, Easterwood et.al. here examine 184 buyout proposals initiated during 1978-1988 all of which were identified from the Wall Street Journal Index (WSJ). Out of the 184 proposals, 149 were successful MBOs and the remaining 35 were unsuccessful MBOs which lost to outside bidders. In case of MBOs, the management being the bidder can protect itself from any competitive bidding and can also go for offering competitive bids as well facing severe market competitions.

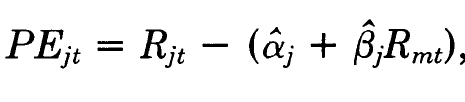

The impacts of alternative control mechanisms have been assessed by using stock return data and offer prices. The impact of an MBO on the stock returns has been assessed through the analysis of stock return data using an event study methodology (See, DeAngelo & Rice, 1984). Then, cumulative abnormal returns were calculated from 20 days prior to the initial announcement date giving clear indication of the takeover activity for the very first time and the accumulation period continued until the offer price uncertainty resolution date.

Then the impact of takeover activity on stockholder returns was assessed studying the association of outsider attempts at control with pre-buyout stockholder abnormal returns. The types and incidence of takeover activity the firms went through have been listed in Table-3.4. As the table shows, there are 83 non-takeover sample and 101 takeover sample. The average cumulative abnormal returns for firms stratified by the presence and type of competition accompanying the buyout offers are given in Table4.5 below. The mean cumulative abnormal returns for each group in the sample range from 25.9% to 43.7% and all means at the 1% level are substantially different from zero.

Hypothesis

“Mean returns to pre-buyout shareholders are equal for the takeover and non-takeover samples”.

Panel-A compares 83 nontakeover offers with the 101 takeover offers. This panel shows that stockholders achieve higher abnormal returns from buyouts with explicit competing bids or implicit outside competition. When the t-test is done it rejects the hypothesis that pre-buyout shareholders’ mean returns are equal for both takeover and non-takeover samples. On the other hand, Panel-B rejects the hypothesis the means and distributions of cumulative abnormal returns for the single bidder versus multiple bidder samples are equal. Panel-C shows 83 and 30 firms facing no outside competition and facing implicit competition.

Thus, the table shows an association between competitions through explicit outside bids and higher abnormal returns to the stockholders. However, there exists no association between implicit outside competition and higher abnormal returns as against the returns experienced by the buyouts stockholders involving no competition at all.

This difference between implicit and explicit outside competitions has been verified in panel-D of the above table, which indicates that the mean and median abnormal return subject to explicit competition are substantially higher than that subject to implicit competition. Thus, higher returns to the takeover sample can be explained by the 71 multiple bid contests and not by takeover activity. This finding indicates that competing bids may limit the ability of the management to pay prices unfavorable to the pre-buyout stockholders and the total buyout gains may determine the depth of explicit bidding competition. Thus, competing bids may occur in case of higher gains from a buyout thereby inducing a positive association between competing bids and pre-buyout stockholder’s abnormal returns.

The impacts of alternative control mechanisms on MBO bidding have also been analyzed here. The effectiveness of three control mechanisms in controlling underbidding has been assessed as well.

The three-control mechanisms are- outside directors as agents for stockholders, stockholder litigation and competing outside bids. Table-3.5 gives the statistics for revisions brought about by the three control mechanisms. The median and mean revisions are about 8% in case of negotiation, 5% and 7% in case of shareholder litigation and in case of competing bids the median and mean are 13% and 17% respectively as shown in the table. The values of the revisions clearly indicate that direct competition has a greater impact on buyout offer revisions compared to the other control mechanisms.

Assessment of the impact of firm’s ownership structure on the incidence and effectiveness of competition for buyouts has been carried out. Here, the ownership structure includes both the concentration of holdings of large outside stockholders and insider manager’s holdings as well. The ownership structure has been presented in Table-3.6 above.

It is clear from the table that the incidence of competition, be it explicit or implicit, depends on the size of managerial holdings. When the firm’s buyout faces little or no control of the offer, insider holdings are significantly higher but the level of manager’s holdings does not influence the form of competition. Moreover, outside ownership concentration has no association with the form or incidence of competitive behavior in buyout offers.

Thus, the empirical analysis of this paper reveals that explicit bidding competition in management buyouts leads to higher stockholder returns and higher offer revisions besides being an effective means of controlling buyout offer prices. The study also concludes that alternative control mechanisms like litigation, negotiation and competition threat have little effect on stockholder returns.

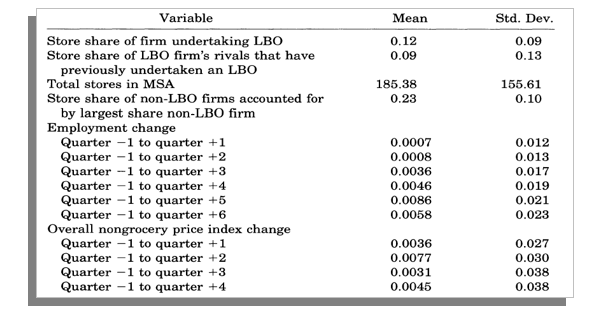

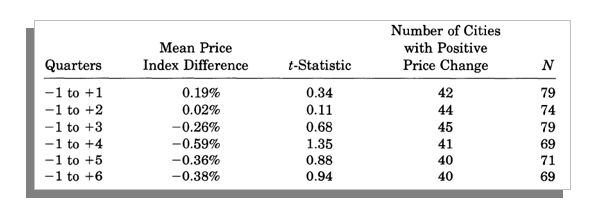

Empirical Analysis- Paper-IV