Culture is a broad term that generally refers to the practices, beliefs and perceptions in a particular setting. However, with the current trend of globalization in the business there has been a surge in international mergers and acquisitions and cultural variation is a major challenge that should be adeptly addressed.

Cultural variation is a very sensitive issue that should be dealt with when organizations are merging together. These cultural as well as other associated differences call for appropriate integration approaches for mergers and acquisitions. Depending on how well the cultural differences are addressed, mergers and acquisitions can be successful.

Leadership is of key essence where mergers and acquisitions are involved and therefore, appropriately integrating culture is very important. The term culture has been deemed an arduous concept hence the numerous definitions associated with it. The different definitions clouding the term culture are as a result of the different national cultural frameworks. This paper therefore, is a detailed discussion of cross-cultural variation with reference to mergers and acquisition.

Culture is perceived to be a very difficult construct that cannot be easily defined. This is due to the fact that Kroeber and Kluckhohn identified more than 164 definitions of the term culture as defined by anthropologists (Dickson, Ram and Jagdeep 9). According to Hofstede (1-3), culture is “the collective programming of the mind” which is applicable to some but not all humankind.

Hofstede’s definition of culture draws a boundary between the various types of culture like national culture, societal culture, organizational culture, and any other kind of culture due to the collective aspect contained in the definition.

Therefore, societal culture can be looked at as the collective programming within a society while organizational culture is within an organization, and so on. Fiske (85) defines culture as “socially constructed constellation made up of practices, symbols, ideas, institutions, competencies, goals, norms, schemas, artefacts, constitutive rules, and changes of the physical environment”.

Foreign direct investment has taken a new turn with regard to the economic and financial world. This is due to the fact that it has recently adopted the form of international mergers and acquisitions. The execution of mergers and acquisitions plays a key role in shaping the world’s economic boundaries. As such there are a lot of international mergers and acquisitions between developing and developed countries.

However, the expectations in financial benefits are not realized as indicate by Auster and Sirower as cited by Majidi (2). Bijlsma-Frankema (192) suggests that these benefits are not realized because mergers and acquisitions are created without placing much attention on deserving issues such as cultural and psychological ones. Instead, financial and business elements are given more priority.

There is a wide gap in as far as cultural variation is concerned between the developed and developing worlds. Therefore, as countries continue to get involved in the free-market economy, it is crucial that managers and involved officials pay attention to cultural factors. This is due to the effects that cultural dynamics have on international mergers and acquisitions and on corporate governance and local adaptation as well.

It has been argued that there is no absolute means of executing effective management across borders. Cultural factors are predominant across borders and influence people’s interpretations and views of their environment, as well as their rationality. As a result, the people manifest differences in behaviours and ways of making decisions as well as in the decisions made.

This being so, it is clear that cultural differences impart certain effects in as far as organizations and businesses are concerned and therefore, the success of mergers and acquisitions greatly rely on how well these cultural differences are addressed. Cultural differences are deemed an asset if they complement the objectives of international mergers and acquisitions, and a liability and risk factor if they conflict.

All in all, the cultural differences should be adeptly handled to minimize risks and enhance the likelihood of experiencing success. This is commensurate with Soros’ reflexivity theory that makes an assumption that people tend to be biased and make decisions without access to complete background information (Majidi 4). In this theory, contrary to the equilibrium theory that assumes that rationality and distribution of information is the same across all cultures, cultural differences are the biases.

The issue of leadership is very important when it comes to international mergers and acquisitions. During this activity, managers or leaders within an organization are sent to another merged and acquired organization in a culturally different setting. The people in the host country determine the success of cross-cultural mergers and acquisitions based on their values and rationality.

According to a research by Dickson, Ram and Jagdeep (13) on cross-border mergers and acquisitions, a 70% failure rate is reported and very few mergers and acquisitions support shareholder value. Culture and communication are deciphered as the main challenging areas that deserve a keen eye when cross-border organizations come together. When different cultures come together in the case of mergers and acquisitions, issues of employee welfare, corporate governance, or customer satisfaction become complicated.

The design process of mergers and acquisitions entail the integration of people with different cultural backgrounds into one corporate cultural entity. The emergent culture is usually that of the acquiring company, or a combined effect of the best elements of the involved cultures. The rationale behind merging lies in the equation: value of AB> value of A + value of B + cost of transaction. Mergers and acquisitions can either be horizontal in that two similar firms combine, vertical in the sense that two firms with different entries along the supply chain come together, and diversification where two totally different companied merge.

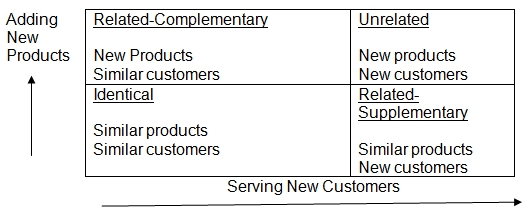

A hybrid approach is deemed a strategically fit integrated approach for international mergers and acquisition. This approach is favourable and in line with the integration mode envisaged in acculturation. This integration approach is characterized by symbiosis and absorption. This is carried with the intention of achieving synergistic gains that result in a synergistic fit as shown in fig 1 below:

Two firms bring together their assets and create value that would otherwise not be achieved if either firm was on its own. In this kind of approach, there should be a matching of aims.

National cultures vary from one country to another and have a bearing on the attitudes and behaviours of the members. According to Geert Hofstede (13-25) national cultural frameworks revolve around four dimensions: uncertainty avoidance, power distance, individualism/collectivism, and masculinity/femininity.

These dimensions show the cultural variation involved between nations. Power distance is associated with the fact that power is not distributed evenly among people and therefore, respect should be accorded to superiors. On the other hand, these superiors should treat their juniors with utmost dignity.

An example of a culture that highly regards power distance is Malaysia. On the other hand, Denmark is a converse of this because it is not a high power distance culture. This differential aspect explains why Korean Air’s co-pilots are submissive to their captains. This shows that the Korean people unlike other national cultures, but like Malaysia, have a high preference for power distance.

The second dimension as described by Hofstede is that which indicates a relative preference for individuality contrast to group. This explains why individualistic cultures, like that of the UK, are described as independent, giving importance to individuals’ rights, and highly values personal initiative and achievement (Hofstede 17).

Venezuela on the other hand is a collectivist culture that values the existence of a group. Collectivist cultures are expected to suppress their individual interests in support of in-groups. Individualist cultures are correspondent with low power distance while the converse is the case. France portrays a unique national cultural framework in that high power distance is in tandem with preference for the individual.

National frameworks also differ with regard to uncertainty avoidance, that is, the capability of cultural members to accept and address vague or risky events. Greece is an example of an uncertainty avoidance culture, whose priority is structure and predictability that give rise to explicit rules to guide behaviour, and stringent laws.

Members of such cultures are reluctant to engage in new ventures where risks are involved such as starting new business, changing employers, or taking up new technologies. Singapore on the other hand is an example of a culture that is characterized with low uncertainty avoidance and as such it accepts unstructured and vague situations where risks are involved.

Another dimension that explains national cultural frameworks is masculinity/femininity. Cultures that uphold masculinity like Japan embrace values associated with male roles such as assertiveness, material success, achievement, and competition.

Feminine cultures on the other hand such as Sweden place emphasis on mellow values such as caring for others, quality of life, and personal relationships. In organizations where feminine culture is evident, there is less emphasis on distinct gender roles and instead, attention is on the overall employee and not bottom-line performance.

Other than Hofstede’s input on national cultural frameworks, other researchers such as Trompenaar as indicated in the table in appendix 1 have developed other frameworks in an attempt to explain the different national frameworks. The different dimensions on national frameworks are important for all business and organizations’ managers since they give a picture of the various differences among cultures.

They give an understanding to different cultures and therefore, when entering a new culture, there should be versatility in order to reach a consensus. These dimensions should be used as a guide during the integration of mergers and acquisitions so that no one culture will feel offended. This is because the issue of cultural variation across borders has been sighted as an impediment to successful mergers and acquisitions due to ethnocentrism that is associated with cultural stereotyping.

In international mergers and acquisitions, one of the approaches is that the acquirer’s culture predominates, making the acquired culture less important. In such a case, the success of such a merger and acquisition is not guaranteed since it gives rise to displeasure among the staff. An example of such an approach yields into a foreign practice effect as will be seen later.

There is much debate on the actual effects of cultural variation on international mergers and acquisitions. Some studies indicate that national cultural differences have a negative impact on international mergers and acquisitions while others talk of the converse. Appendix 2 gives a brief overview on the various theories and models that are mainly postulated while explaining how culture influences international mergers and acquisitions, as well as the integration mechanisms used.

International mergers and acquisitions result in culture clash, which affects the involved businesses in various ways. To begin with, there is a reduction in shareholder value for the acquiring firm. Organizational restructuring and employees’ commitment and co-operation are also affected. The latter is due to the confusion, distrust, and hostility attributed to cultural variation/distance. Operational performance of the acquired firm is jeopardized, and so is the turnover of the acquired managers.

In a comparison of two national cultures as indicated by Majidi (1), Swedish culture unlike the American one is likely to use integration as the integration mechanism of acquiring a firm. This is because Swedish firms adopt a corporate culture that minimizes culture clash but instead promotes jointly negotiated consensuses.

The Swedish culture therefore is perceived to adopt integration in that it does not impose its values and practices on another. This imposition of cultural practices and values of one culture, on another, results in assimilation, a kind of integration approach associated with both positive and negative outcomes.

In Sweden, annual vacations are mainly scheduled for July while the Americans schedule theirs in summer. A merge between organizations from these two nations would clearly result in a breach of interests like the 1995 merger between two pharmaceutical companies: Upjohn Company of the United States and Pharmacia AB of Sweden.

Since the US was the acquiring firm, it used a poor integration approach where dominance was prevalent: assimilation. As a result, there were strained international ties between the two firms. The American superimposed their policies on the Americans such as their drug and alcohol testing policy. Such an approach marked by dominance and superimposition on another culture results in resentment and even xenophobia.

Regardless of the fact that the US Company was accommodative to some but not all of the local practices and preferences later, the approach initially taken had a significant effect. With reference to Hofstede’s cultural dimension of individualism versus collectivism and power distance, the Swedish and American cultures greatly conflicted.

This kind of culture clash adversely affected the general performance of the outcome. Ideally, international mergers and acquisitions are meant to complement one another and the approaches to cultural integration in appendix 1 are a better way of forming mergers and acquisitions instead of the imposition indicated by the American and Swedish cultures example.

The integration used by international mergers and acquisitions should be good enough to accommodate all the factors that pose a threat to a successful collaboration. Since culture has been identified as a key reason for failure, culture integration should result in a cultural fit or joint culture as opposed to social construction where it is believed that lays emphasis on cultural transformation.

Cultural differences are manifested in various forms. One such form is language barrier which reduces the amount of knowledge/information flows. These flows are also affected by misinterpretation and lack of willingness to disseminate information across cultural boundaries.

Lack of a clear understanding between staff and/or their managers can result in adverse effects for any merger and acquisition since language and communication are the means through which business processes are executed. In the context of cross-cultural management, there is need to understand the culture at a particular organization for successful merging and acquisition.

Realizing the expected relations during the merging and acquiring process is very essential and depends on developing structures and procedures that can be integrated in both cultures equivalently.

A cultural integrated approach, which should be the lime-light of every organization, is the much preferred approach. This is because more than 85% of mergers and acquisitions fail merely due to conflict in culture.

An integration based on culture makes it easy for the people to understand “what is happening, why, what it’s about, and a sense of ownership makes it possible for them to engage in and influence the outcome” (Sinclair 1). This approach addresses the issue of culture up-front and lowers the levels of stress and uncertainty within an organization.

The hybrid approach, in other words the integrated approach is used to ensure that companies enjoy more benefits while as a double entity instead of being just a single one. This approach is associated with gain for client base as well as resources. The cultural integration approach is very important and the issue of culture should be addressed early enough. Unfortunately most managers and executives make an assumption that corporate cultures will somehow make it but this is not usually the case.

What happens eventually is that post-merger voluntary attrition takes effect and increases with 10-70% if the cultural issues remain unaddressed. Some of the staff may remain but they would not be effective due to displeasure.

The first 3 to 6 months of post-merging is associated with uncertainty if cultural issues are not resolved and may not yield positive operating results. A cultural integration approach is very essential especially for the due diligence decision making processes that need involved cultures make agreements on the day-to-day operations of the business (Sinclair 1).

Conclusion

Culture is the gist of any business since it is the norms, values, belies, practices and daily undertakings of the general nation/society and trickle down to the firm/organization. As the business world takes a new approach to utilize the liberal economies of scale, international mergers and acquisitions, have become the preferred choice of foreign direct investment (FDI). During the acculturation process, attention should focus on language, culture fit, and communication.

Works Cited

Bijlsma-Frankema, Katinka. “On managing cultural integration and cultural change processes in mergers and acquisitions.” Journal of European Industrial Training 25.2–4 (2001): 192–207. Print.

Dickson, Marcus, Ram Aditya, and Jagdeep Chhokar. Definition and interpretation in cross-cultural organizational culture research: some pointers from the GLOBE research program. 1999.

Fiske, Alan P. Socio-moral emotions motivate action to sustain relationships. California: University of California, 2002. Print.

Hofstede, Geert. Culture’s consequences: International differences in work-related values. London: Sage, 1980. Print.

Majidi, Mehdi. “Cultural factors in international mergers and acquisitions: When and where culture matters.” Interntional journal of knowledge, culture and change management 6.7 (2007).

Sinclair, Keith A. Cultural integration process for mergers and acquisitions. 2003.