Introduction

Law enforcement agencies represent a unique environment different from other workplaces. As significant as any change has been the expansion of geographic boundaries through technological advances in communications. Because of the relatively low costs of long-distance telephoning, business and social relations can be maintained with people all over the nation, and there is a tendency to keep sporting events, or violent crime. Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs allows explain motivation and practices in law enforcement agencies and analyze work relations and communication, rewards and attitudes of law offices.

Theory Overview

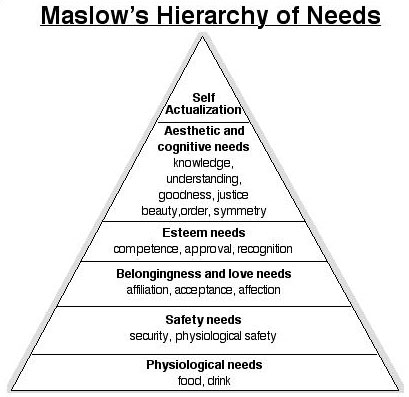

The behavioral management concept was primarily triggered around 1943 by a psychologist, Abraham Maslow, who developed a hierarchy of needs model. The needs range from physiological as one of the first needs to be fulfilled up the ladder to Maslow’s peak of self-actualization (Maslow 5). As originally proposed, each lower need had to be filled prior to stepping up to a higher need. Today, however, most behavioralists believe that the fulfillment of the needs can be going on in several steps at the same time. It should also be noted that the Maslow model can be considered as a selfish model in that the peak of his model ends with self-actualization, or “I have achieved my ultimate goal and peak”; “I am number one.” The emphasis is on achieving one’s own gratification and happiness, even at the expense of others (Maslow 10, see Appendix). Almost every student who has taken a basic psychology course or a basic behavioral management course since World War II has been exposed to this model and theory. It is a model and theory that, if stopped at this point, promotes selfishness in the individual and leaves no one truly satisfied. As can be seen on the left-hand scale of the figure, a person is only about 85 percent satisfied at most within himself or herself when the self-actualization state has been reached (Baldoni 42).

Once his basic needs for food, clothing, and shelter are satisfied, he wants friends and to get folksy and group. Once these needs for belonging are satisfied, he wants recognition and respect from his fellowmen and he wants to achieve independence and competence for himself. And once these needs for status and self-esteem are satisfied, he seeks self-fulfillment, freedom, and higher and higher modes of adjustment and adaptation (Maslow 11). Maslow underlines that:

- Not until the lower-order needs are satisfied will the next higher-order needs become greatly activated.

- One man has satisfied his first two orders of needs — subsistence and social — they cease to be powerful motivators of his behavior. Once he has broken through this level, this property no longer applies.

- Once his needs for status, knowledge, and self-fulfillment have become activated, he becomes greedy. He cannot satisfy them enough and thus they remain never completely satisfied.

- He seeks at great cost, even sometimes at the cost of subsistence and social needs, for more and more satisfaction of these needs for status, self-esteem, and self-fulfillment. But his hunger for these things does not appear until his subsistence and social needs are all reasonably satisfied. But in fulfilling his wants at each level, the struggle goes on; there is a cost attached, i.e., the principle that “you can’t get something for nothing” still operates (Maslow 21).

Each reward has its corresponding cost and the higher the reward the greater the cost, as well as the higher the cost the greater the reward is believed to be. Thus in this struggle of fulfilling their increasingly complicating wants, many men fall by the wayside. Either (1) they are unwilling to pay the costs required for the satisfaction of their higher wants or (2) their situations offer little or no opportunity for their satisfaction. Every man wants to grow but he may not be willing to pay the price or, although willing, may not have the opportunity to do it. As a result, many of man’s higher wants remain dormant or thwarted (Maslow 34). Dissatisfied needs do not remain still. They continue to flourish at the level at which the upward development stops or at levels lower to it. This lower level elaboration, however, should not be confused with growth; it is symptomatic of the frozen state: an endless elaboration at one level of certain need satisfactions such as, for example, the endless pursuit of groups and friends for the emotional support they provide or the endless pursuit of more and more status symbols and the needs for the recognition they satisfy.

Law Enforcement Environment

State legislatures are the most appropriate agency to undertake control in this area. But their reluctance to do so in the past is not likely to change in the future. In any event, assuming they eschew the role of active rule maker, legislatures have three basic options in choosing who should develop law enforcement policies. First, the state legislatures could decide that arrest rules are to be made by a state agency and then be applicable statewide (Cook 22). This choice would reinforce the state’s role in law enforcement. Second, the legislatures could permit local governing bodies or police agencies themselves to formulate selective enforcement rules. This approach would constitute formal recognition of the local role in law enforcement. A third possibility could be some combination of state and local involvement in the rule-making process. The major advantages of placing responsibility for rule development in a state agency are that it encourages uniformity in the application of state criminal law, centralizes responsibility for rulemaking, and facilitates the allocation of greater resources to finance and staff the police rule-making effort. Uniform application of the criminal law is a significant consideration in designating a police rule-making body. Although state agency development of rules does not guarantee the uniform application of such rules, it would ensure that the same rules are in effect statewide and substantially limit the ability of local law enforcement officers to put their own “gloss” on the rules (El-Ayouty et al 2000). Centralizing rule development in a state agency also would have the advantage of concentrating policy-making authority and responsibility. One agency would be legally and politically accountable for the development of rules. Finally, centralization would enhance the likelihood of greater access to funds and personnel to assist in rulemaking. Broad institutional participation at both state and local levels is critically needed. The major question, however, is the nature of such participation (El-Ayouty 55). The involvement of local government officials such as the mayor and city council would probably broaden the political support for and the legitimacy of formulated rules. In light of the limited involvement of mayors and council members in the past, it is unrealistic to expect any major changes in the future (Robbins 81). Nonetheless, after the police have drafted rules, the dissemination of rules to these officials would invite reasoned and official responses, while increasing the opportunity to broaden institutional consensus on the rules. Initially, because of the tradition against monitoring local police and feelings of lack of expertise, not much more than review and comment might be expected; however, that would be a substantial advancement over the present situation (El-Ayouty et al 2000).

Impact of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs on Law enforcement Personnel

Similar to other professions, law enforcement officers are influenced by L the basic subsistence needs which play such an important role in the worker’s relation to management. Through steady employment and good pay, law enforcement management can satisfy these needs of workers. But, once satisfied, they become less and less important and the higher needs become more and more important. As these higher needs become more important they cannot be satisfied by management in quite the same direct way that the lower needs are satisfied (Robbins 83). And so from these peculiar properties, certain important consequences follow for management. Because law enforcement management has been so successful in satisfying its workers’ subsistence needs, and because workers whose subsistence needs are satisfied are no longer motivated to satisfy these needs, management can no longer use its traditional rewards to motivate them (Zendzian 92). No amount of good wages, fringe benefits, and good working conditions in and by themselves will motivate workers to give more than minimum effort. Thus law enforcement management seems to be left with obsolescent motivational tools on its hands that have not been “written off” for new ones.

In law enforcement agencies, management can provide workers with jobs (rewards) that satisfy their subsistence needs, it cannot provide workers as directly with those rewards which allow them to satisfy their higher needs. It cannot provide workers, as directly as it hands out jobs, with friends, with the respect of their fellows, with self-respect, with independence, or with the satisfaction of their needs for self-development and fulfillment (Zendzian 72). Although it can provide the conditions which would allow these needs to be satisfied in relation to the goals of the organization, it cannot push them, direct them, or lead them in this direction, kindly but firmly. To make the situation even more serious, management cannot provide these conditions easily. The very way that work is traditionally organized tends to make for more and more simplified and limited jobs, requiring less and less skill and responsibility, utilizing less and less of the worker’s capacities, and eliminating more and more meaning from his work. It thus becomes more and more difficult to satisfy these new needs under these conditions (Robbins 84). Thus management finds itself in a tough situation. By satisfying its workers’ subsistence needs it has lost its conventional controls for motivating them. It has released new wants which its old motivational tools cannot satisfy. Moreover, it has unwittingly organized its work in ways that do not provide the conditions that will allow these new needs to be satisfied. As a result, many of the workers’ new needs for membership, status, and growth become thwarted and so-called human relations experts are hired to deal with these thwarted needs which management has unwittingly produced in the first place (Zendzian 92).

In law enforcement agencies, given the traditional conception of its task and given the motivational situation to be as we have described it, the frozen state must be a consequence (Norris and Armstrong 1999). The man’s four basic needs can be classified as:

- subsistence,

- social or membership,

- recognition or status,

- growth or self-fulfillment needs (Baldoni 44).

Workers’ subsistence needs partially into account in connection with the emergence of a group output norm. The ways of organizing work in the law enforcement field are not too different from the conventional pattern and thus give researchers no reason to believe that these needs would be highly activated. Therefore researchers assume that a social structure would emerge from the workers’ struggles to satisfy essentially their membership and status needs under conditions that, granted, are not too favorable, but at least are possible of some realization. Researchers expect to find some of them satisfied, some of them thwarted, and as a result, certain productivity and satisfaction patterns would emerge (Whyte 62).

That after satisfying their subsistence needs workers to try to satisfy their needs for belonging, association, friendship, and love, while obvious, is nevertheless important. And that this occurs in spite of the fact that workers are not often organized as task teams but as individuals with fixed and limited jobs requiring little or no interaction with their fellows, offers some indication of the strength of these needs as motivators of behavior (Strauss 73). Because most managements organize the workplace in a way that allows such few opportunities for the development of these social needs in relation to organizational goals, it is not surprising that they develop, so to speak, on their own and unrelated to them — and that the social structures that emerge from the attempts to satisfy them become essentially the workers’ and not management’s creation. As such, they become thereby of great importance to workers and at the same time of great threat to management. In law enforcement agencies management cannot “control” them in terms of their conventional motivational tools. The more they try to control and interfere with them, the more they flourish in ways that become more annoying and unmanageable (Gooch and Williams 63).

The researcher identifies that something of more immediate concern to management is that in these transactions and exchanges of nonmaterial goods, the workers are the chief dispensers. The law officers and not management are dispensing the powerful rewards and punishments that determine the productivity and satisfaction of its members. Membership or isolation is the reward or punishment; conformity or nonconformity is the cost and the difference between them is the profit or satisfaction (Gooch and Williams 75). In this exchange of powerful motivational goods, management’s role tends to be overshadowed. Why pay and job status differentials seemed to operate so little as rewards in the group we studied seemed to us to indicate that they were not clear and unambiguous rewards in the minds of the workers. Their status strivings were so intertwined with their membership needs that they could not be separated out clearly, simply, and unambiguously. There were some workers who were still so busily engaged in satisfying or coming to terms with their membership needs that their strivings for recognition and status remained dormant or thwarted (Cook 49). There were other workers whose external status needs were being realized but whose work situation provided little opportunity for satisfying them in the direction of organizational goals. Hence their strivings for recognition were developed only within the framework of what the social structure allowed. The status strivings for job competence and leadership of the high status isolates, for example, were restricted to what their relations vis à vis the regulars permitted. The status strivings of the high-status regulars were manifested more in the direction of internal status, prestige, and social leadership than in the direction of job competence and task leadership (Gooch and Williams 88).

Also, Maslow pays special attention to the thwarted needs for a well-established job status that existed among many of the low-status law enforcement officers. Even though these needs are related more to certitude and justice than to recognition, we shall discuss them here. As our study showed, there was much more opportunity for high status than for low-status workers to realize these needs for well-established job status. When they were realized, they tended to elicit more responsible behavior, even though it did not take the form of high output. This was true for both the high-status regulars and the high-status isolates where we found the social leaders and task leaders respectively of the group (Baldoni 43). These needs were less realized among the low-status workers. Under conditions of employment where young and inexperienced boys and girls can do the same jobs and receive the same pay as older and more experienced men and women, it is more difficult for the older and longer service workers to realize a well-established job status. And when it is not realized, responsible attitudes are difficult to develop. To the older and more experienced worker who has given many years to his job, this situation makes little sense and violates seriously his sense of justice. If no matter how much responsible behavior the older worker can show, he cannot obtain recognition from either management or his fellows, he is more likely to seek what satisfaction he can obtain by being irresponsible or by holding to a personal standard of conduct that he believes to be superior to that of his fellows. In the latter case, virtue is its own reward. Under present conditions of employment, it is difficult for management to satisfy these needs for a well-established status, particularly at the lower levels. And it is a serious question whether management should try to satisfy them by manipulating groups or status symbols. But these thwarted needs deserve attention because until they are better recognized and understood, there is little chance that workers will feel like directing their efforts to organizational goals. Something much more important to them has to be satisfied first (El-Ayouty 23).

When the workers’ subsistence needs are no longer paramount and when their needs for membership, status, and self-development become activated. When workers start trying to satisfy these needs on the job. When the way work is traditionally organized allows little or no opportunity for the satisfaction of these new needs and thus they become thwarted (Baldoni 55). The regulars are the setters and policers of the acceptable modes of behavior, the persons “in the know” in an organization. They know the game of how to get along and how to get ahead and how “to keep your nose clean” at the same time. Around them tend to rally the forces of conservatism, of keeping things as they are and were in the past and therefore always should be. They protect the organization from too rapid change and thereby serve a useful function. In the small group, we studied the regulars were the arbiters of their social life.

Conclusion

In law enforcement agencies, workers and law officers are influenced by basic human needs identified and explained by Maslow. These conditions vary from group to group and organization to organization and nothing useful is gained by generalizing from the conditions obtained in this particular group. But even though the conditions be different, every group and organization have their regulars. There are many officers who feel that they could best fulfill their own needs by directing their efforts to the goals of the organization. In the establishment of an intricately elaborated social structure that would satisfy their minimum social needs.

Appendix

Works Cited

Baldoni, J. Great Motivation Secrets of Great Leaders. McGraw-Hill; 1 edition, 2004.

Cook, K. R. Asphalt Justice: A Critique of the Criminal Justice System in America. Book by John Raymond; Praeger, 2001.

El-Ayouty, E., Ford, K. J., Davies, M., Carter, M. Government Ethics and Law Enforcement: Toward Global Guidelines. Praeger Publishers, 2000.

Gooch, G., Williams, M. A Dictionary of Law Enforcement. Oxford University Press, 2007.

Maslow A. H., Motivation and Personality. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1954.

Norris, Clive, and Gary Armstrong, The Maximum Surveillance Society: The Rise of CCTV, Oxford: Berg, 1999.

Robbins, S. Organizational Behavior. Pearson Higher, 2002.

Strauss, M. Reconstructing Consent. Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology, (2001), 211.

Whyte William Foote. Money and Motivation. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1955.

Zendzian, C. A. Law Enforcement Officer: Guidebook for Background Checks and Polygraph Tests. Test Better Now, LLC, 2002.