Introduction

The Meiji restoration of 1868 stands out as a major event that resulted from toppling down of the Japan’s Tokugawa dynasty. It gave rise to the revolution of Japan from the traditional and dominant culture. The medieval forms of development to modern era was also captured in the restoration. As this paper will reveal, imperialism in Asia acted as the key factor that dictated later orientation of the Asian nations in the continent. Before the restoration, imperialism in Japan by the Tokugawa Ieyasu dynasty was intense (Anderson 252). The renewal converted the nation from traditional life models to highly advanced systems. As majority of historians agree, it served as the main molding tool for later governance and regional difference (Anderson 252). It is against this backdrop that this paper explores the Meiji restoration and also uses pictures and image arts to appreciate the differences in time and models that were dominant during the imperial rule. The paper intrinsically brings out the critical outlook of the transformations that took place during this period.

Efforts against imperialism

In order to effectively understand the implications of imperialism in Japan, it is critical to understand its background thoroughly. Historians indicate that before the close of the nineteenth century, the struggles by western nations to get colonies in Asia greatly intensified and culminated into other upcoming powers in order to generate similar interests. Imperialism scholars indicate that the desire to maintain external colonies was quite multifaceted in several ways. This was the same case with Japan in the last decades of 19th century and early years of the 20th century.

It is worth noting that imperial authorities of the Tokugawa Shogun encountered massive rebellion from the local communities and leaders. In order to maintain effective control over the lucrative business and trade in Japan, the imperialist used force and hampered local development. This type of interruption eventually culminated into tight rebellion from the affected communities (Anderson 183). Participants of the rebellion were hanged in public, shot dead in their home compounds and slaughtered in a bid to create intense fear and therefore prevent such events from recurring.

Rebellions towards the Tokugawa Shoguns had vast negative impacts to both the dynasty and Japanese citizens (Ferguson 146). In Japan, the effects culminated into massive destruction of property, resources and even lives. This was very critical in the freedom of Japan from its oppressors. Darwin indicates that the heavy loss of lives and property was quite critical in the birth of a new era of economic development and dispensation (135). It was not until the imperial rule was brought to an end that Japan assimilated a major economic development in the region. Of greater importance was the gross deprivation of economic resource and revenue that were taken by the Tokugawa leadership bearing in mind that it controlled the whole of Japan during that time (Ferguson 146). Under this consideration, the country was left with diminished resources and consequent decline in revenue. The era was also coupled with depleted resources that were needed for economic growth and development.

Meiji Restoration

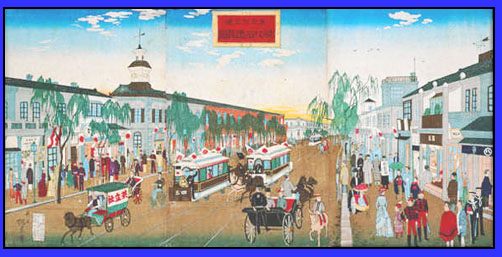

In the wake of the new government (Meiji regime) in Japan, national realignment demanded that more resources were available through trade and intensive military control. The latter managed to maintain the necessary security against external forces (Anderson 255). As the diagram above illustrates, the military sector of the nation was to be established and as such, its army was modeled to resemble the British navy and the Prussian force. Initial treaties were therefore forced upon the Korean rulers. As a result, it culminated into the intensified presence of the Japanese rule until their defeat during the World War II.

Darwin points out that the Meiji revolution was a major political and social event that led to huge structural reforms (260). Before the restoration, Japan was under subjugation and was forced by the Tokugawa Shogun and western colonialists into treaties like other nations in Asia. This undertaking significantly favored their superiors both economically and legally. The defeat of Tokugawa paved way for Japan to re-establish itself under a new government that ensured equality among all of its citizens.

Trade, development and exploitation of resources

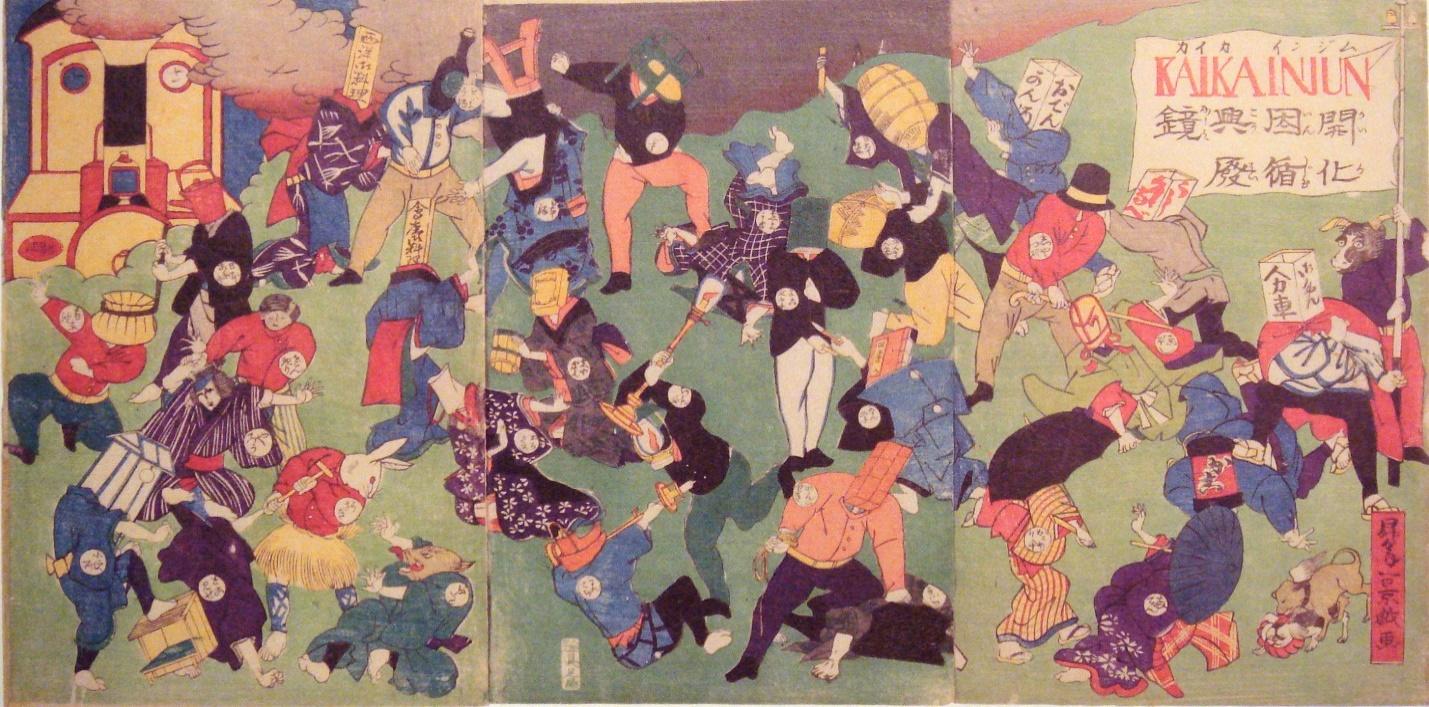

It is worth noting that prior to the onset of industrial revolution, the need for supplies to maintain industries was very critical. Following this consideration, the Japan’s new government sought to accelerate high levels development that could enhance its ability to utilize the resources in the country (Caprio 12). Its citizens and government officials embarked on ridding the nation from old and traditional structures to pave way for new structures. In their place, Meiji reformed the education system, constructed modern homes and houses, and also ensured that finances were available to construct the textile industry. The diagram below is an important piece of art reflecting efforts by the Japanese citizens and the government to get rid of the traditional systems. From the diagram, it is evident that graphic events took place during the Meiji restoration especially in regards to transforming the traditional system of governance that mostly oppressed the ordinary citizens.

Historians indicate that the Japanese government under Meiji strongly invested in infrastructural development so that it could be quite easy to facilitate its security inference in the country (Caprio 10). It is worth noting that during this period, the government sought to incorporate Korea fully into its boundaries. As a result, a system of colonial mercantilism was assimilated so that it could enhance better exploitation of the different resources in the country (Caprio 10). Therefore, raw materials such as timber, food products, and most importantly mineral resources were equally exploited. It is worth noting that the initial onset of Japanese imperialism was very cruel bearing in mind that the government employed gunboat diplomacy to force the Korean government in accepting the Japanese occupation (Bush 123).

Sino-Japanese War

In the process of developing the nation and soliciting for resources, conflicts of interest to control Korea arose between Japan and China. This led to the Sino-Japanese War of 1894-95 (Shinichi 180). Under the leadership of the new government, Japan organized its army and consequently fought and defeated China.

It is imperative to note that the different imperial governments that took control in the region employed various types of mechanisms with the aim of maintaining a strong grip and control of their subjects (Bush 123). This culminated into different effects to particular countries especially in regards to their mode of governance, religion, and culture. It is worth noting that Japan’s imperialism in Korea was put in place in order to re-fix and redefine its position among the modern colonial powers such as British and France and therefore kicked off in the 20th century (Shinichi 180). On the other hand, the western imperialism had long been established by the 20th century. As a result, it led into long lasting effects within the affected region.

Conclusions

It is from the above discussion that this paper concludes by reiterating that imperialism in Asia acted as a key factor that dictated later orientation of the Asian nations, and particularly Japan, in the continent. Through involvement of the Japanese people in a bid to secure its social, economic and political freedom from the Tokugawa dynasty, most of the traditional systems were dropped and the new government assimilated a new leadership model exhibited by Meiji. Most of their latter systems such as education systems, trade, and medical orientation mimicked those of the imperial rulers and played an important role in changing the structure of the nation. It is also vital to mention that the Meiji restoration marked an important historical era in the history of Japan. From the images displayed in this essay, it is apparent that the historical era was indeed remarkable largely due to the activities and operations that took place.

Works Cited

Anderson, Richard. “Jingu Kogu Ema in Southwestern Japan: reflections and anticipations of the Seikanron debate in the late Tokugawa and early Meiji period”. Asian Folklore Studies 61.2 (2002): 247-270. Print.

Bush, Barbara. Imperialism and post-colonialism (History: concepts, theories and practice), New York, NY: Longmans, 2006. Print.

Caprio, Mark. “The Japanese Annexation of the Korean Peninsula: A Case of Peripheral Colonial Expansion?” Sophia International Review 24.4 (2002): 1-15. Print.

Darwin, John. After Tamerlane: The Rise and Fall of Global Empires, 1400-2000, Boston, MA: Penguin Books, 2008. Print.

Ferguson, Niall. Empire: How Britain Made the Modern World, New York, NY: Penguin Books, 2004. Print.

Shinichi, Arai. “Looking at legitimacy and illegitimacy from a historical perspective.” Seoul Journal of Korean Studies 18.2 (2005): 175-194. Print.