Introduction

A distinctive way to impart knowledge is through the arts. According to El Refaie (2019), fine art is a unique mode of knowledge and thought. He continued that the experience of great art is essentially a sharing of knowledge that has been considered as adding to an evolving conception of the arts as communicative knowledge. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, new concepts in art and philosophy began to take shape due to the Industrial Revolution. Modern artists deviated from conventional methods by utilizing new techniques to produce forms and colors, for instance, by experimenting with color, French Impressionists like Édouard Manet and Claude Monet could portray their interpretations of everyday objects and nature.

Therefore, the purpose of this dissertation is to research modern art and postmodern art in Malaysia’s art scene in light of the change in art throughout the Industrial Revolution. Furthermore, understand the socioeconomic and political contexts that have molded the developing middle class in Malaysian artwork. This is made easier by the main research question, which is how Malaysian artists’ preoccupations have changed from Malay/Islamic-centric artistic inclinations to a postmodern viewpoint. Modernist artists of this era frequently propagated idealistic ideas of society and tended to glorify simplicity, clarity, and formalism. For instance, Russian constructivists reflected political beliefs and promoted utopian goals using simple geometric patterns. However, postmodern art, which dominated the later part of the 20th century, originated as a response to modernism after World War II and criticized previously held beliefs about high culture and progress. Pop art, conceptual art, Neo-Dada, minimalism, land art, Abstract Expressionism, performance art, and feminist art are just a few new forms and artistic movements that make up postmodern art. Over time, Malaysian society’s artistic production can be observed to reflect this feature of the modern and postmodern art scene (Ker et al., 2020). Malaysia is considered a multi-country where residents of the three main ethnic groups—Malays, Indians, and Chinese—coexist and cowork together. The Chinese, who practised a combination of Buddhist, Confucian, and Taoist ideological practises and spoke one among numerous Chinese dialects in addition to Mandarin, as well as the Malay and indigenous “Bumiputera”, who were primarily Muslim and spoke the language of Malay. The British uniquely governed each faction. To be formally “recognized” by the colonial overseers, people considered it in their self-interest to identify as a particular representative of one of the groups.

The three cultures coexisted mostly apart since the British made little effort to foster a shared Malayan peninsular ideology among the inhabitants (Mamat et al., 2022). To establish a parliamentary democracy with the primary objective of creating a unified multicultural country with a shared identity, elite members of the three “ethnicities” from various groups came together at the moment of independence. A single education framework and shared language were considered key elements for achieving this. Due to its different cultures, initiatives were made to achieve national unity through various political, economic, and social avenues. Predicated on the multicultural paradigm, the school was considered the most appropriate venue to promote national unity (Nordin et al., 2018).

In addition, the national government made an effort at every level to unite the three “racial”/cultural groupings represented in different contexts into one nation. For instance, new national festivals, like Independence Day, were established while the primary festivals of all ethnic groups were recognized as global festivals. The majority dialect in school systems was to be Malay, but students were also expected to acquire English as a secondary language and be exposed to Tamil and Chinese. Malay people would learn Arabic (Mamat et al., 2022). The New Economic Policy (NEP) of Malaysia was implemented in 1970 as a part of a set of reforms following the political unrest in May 1969. To foster circumstances for national unity, it intended to “eradicate poverty” and “restructure society to erase the connection of race with the economic function” (Lee, 2022). The approach significantly enhanced the output of farmers and skilled Indians while fostering multiculturalism.

Malaysia’s diverse social, political, and cultural spheres exhibit a distinctive quality that highlights the country’s singular diversity. The cultural landscape of Malaysia has seen enormous upheaval since the 1990s. Its art scene has recently developed into an ongoing, thriving, and constantly evolving art initiative. The development of globalization and cyber technologies, notably the internet, have also had an impact and diverted the energies of artists and the arts in quite different ways (Ker et al., 2020). Since 2006, as the broad international desire for Asian art has filtered down to a handful of Malaysian artists, the price of some artists’ works, including those of Ahmad Anwar, has skyrocketed. Some of them have even received commissions from European and Japanese museums. Some of them have achieved international recognition. Some have additionally received invitations to take part in renowned biennales around the globe.

From this, it can see that the situation of Malaysian arts, particularly modern art, is very different from that of Euro-America, even though there have been numerous beneficial achievements in this field. However, most writing on art still takes the form of a report and is only written for exhibition catalogs (El Refaie, 2019). There are extremely few reviews and critiques. Furthermore, these changes have only been briefly examined concerning the growth of postmodern art in Malaysia, and there is still much to learn about them. For instance, Redza Piyadasa signifies the transition in Malaysian art evolution from modem fixations to postmodern ones in his two articles from 1993 (Abdullah, 2018). Although the topic of transition has been discussed before, studies outlining art historical documents of Malaysian art have noted a changing trend. According to Abdullah (2018), Piyadasa accentuated how the younger generation of artists appeared unsatisfied with many renowned artists’ aesthetic choices during the 1990s. Despite the government’s emphasis on the Malay/Islamic culture as the foundation of national identity, they appear to be giving up on the search for national identity. Produced art is starting to challenge the Malay/Islamic creative ethos and become more diversified. Faceted art forms are now being utilized, including performances, installations, and electronic media like video and photography. It investigates the background and interpretation of Malaysia’s modern and postmodern art scene.

Postmodernism has been one of the most frequently used terms in contemporary cultural discussions, even in the context of Euramerica (Khalefa et al., 2020). This term is used in various contexts depending on how history and culture are applied. For certain philosophers, postmodern is referred as a culture driven by televisual symbols. There are, therefore, discrepancies in how these concepts are understood when discussing postmodern art and modern art outside of Euramerica. This is due to the requirement for contextualization regarding one’s historical and cultural setting when reading and comprehending works of art (Ker et al., 2020). This is especially true of art created in developing nations; despite the common usage of such terminology in art discussions, these works’ idiosyncrasies, genealogies, thoughts, and understandings are very dissimilar from those in Euramerica.

Malaysia is praised for being a multi-ethnic nation; however, this may provide a number of difficulties for the idea of national cultural identity. People in multicultural environments may create and exhibit identities that mirror and even integrate various sources because they are subjected to various cultural elements or have roots in different cultural groups. This renders it challenging for such a person to support a specific culture or a social identity unique to the United States.

As a result, ethnic and cultural manifestations in Malaysia continue to be multicultural and diverse in the form of music, poetry, theatre, dance, and short stories. Even in the past twenty years, there has been a change in the focus of artistic endeavors toward problems of concern, including materialism, gender, and environmentalism. A few works have also questioned societal concerns like social fairness, freedom of speech, human rights, and Malaysian democracy. As many Malaysian artists have started to withdraw from painting and sculpture in favor of new methods and media, the blending of diverse artistic disciplines has also impacted the course of Malaysian art. In this regard, the discussion on postmodernism and modernism must take place in this context.

Therefore, this dissertation looks at several topics in this setting. It examines the forms of Malaysian art scene postmodernity, drawing on the disciplines of art history, sociology, cultural history, and Malaysian Studies in precise. It discusses the transition from a modern to a postmodern viewpoint in the setting of Malaysia’s postmodern situation, which is associated with the new Malaysian middle class that is rapidly expanding. Furthermore, it examines how Malay/Islamic-centric inclinations have given way to a more postmodern worldview and the use of postmodern artistic techniques among Malaysian artists. This article will look at how many facets of the post-colonized and globalized society have influenced modern artists. It will evaluate the creations of three modern artists, including Yee I-Lann and Kok Yew Puah. The research will look at certain texts from their corpus to show how they question ideas of geography and national identity. Can one eliminate political and cultural effects on the Malaysian art scene? This is the main query of the thesis.

Modern Malaysian Art and Its Postmodern Situation

The Birth of Modern Malaysian Art

It is still unclear exactly when the contemporary art movement in Malaysia started. According to Ker et al. (2020), the contemporary art movement in Malaysia began some 60 years ago. Historians and artists have different perspectives on this, though. According to Khalefa et al. (2020), who hold the same perspective as Abdullah (2018), the beginning of Malaysian contemporary art, Modern art activities in Malaysia start in earnest only in the immediate era after World War II. This unusually tardy development in Malaysia may be linked to the British, whose secession of parts of the Malay Peninsula began in 1924 and who generally did not support cultural activities (Khalefa et al., 2020). In an essay titled “Contemporary Malaysian Painting,” Zainol Abidin (1996) underlines this issue in favor of the argument made by Kandinsky and Piyadassa that Malaysian artwork began around the 1920s.

When Malaysian artists who had obtained their training abroad returned to the country with western ideas in the 1960s, Malaysian contemporary art was at the height of its experimental phase. They based their understanding of the cosmos on global perspectives deemed fashionable at the time, pushing the boundaries of freedom of expression to the very edge. Due to this, many works were created throughout the period, with no clear definition of what could be considered Malaysian contemporary art (Khalefa et al., 2020). Additionally, most of the works created during the period lacked a clear point of reference to traditional characteristics, rendering them irrelevant to advance national identity. The artistic methods were open-ended, diverse, and eclectic, as was to be expected in a scenario where there were, as of yet, no officially imposed definitions regarding what the national culture should be.

However, following the racial disturbances in Kuala Lumpur in 1969, which saw deadly fights between the ethnic groups, Malay sentiment was reignited in the middle of the 1970s. Malaysia, a young country, was severely rocked by the crisis, and the government made significant attempts to mend racial relations between the ethnic groups to prevent a recurrence of the incident. The First National Cultural Congress was established in 1971 to encourage artists to convey a sense of pride and identity through their work. The perspective that affected the nation’s greater interest in exhibiting the national culture today influences the artists’ ideas, thanks to Congress’s unmistakable sense of direction.

National Cultural Congress

Malaysian visual artists were entirely unprepared when May 13, 1969, race riots occurred. The fact that Malaysia’s new nation had been created on weak foundations eventually dawned on the more serious artists. This interethnic unrest on May 13, 1969, between the Malays and the Chinese was undoubtedly the turning point for Malaysian artists (Abdullah, 2020). Additionally, two artwork pieces, that of Ibrahim Hussein’s and Redza Piyadasa were created soon after the incident on May 13 effectively exhibited a novel form of visual imagery. The riots were the subject of Ibrahim Hussein’s sad piece May 13, 1969 (1970), which featured a blackened out Malaysian flag and the terrible number “13” etched beneath it (Abdullah, 2018). The other piece was an installation by Redza Piyadasa, which was created in 1970 and was likewise titled May 13, 1969. It displayed a life size coffin standing erected with a delicate reflected mirror. These two upsetting pieces, both inspired by the horrific racial riots, signaled a new, albeit somewhat delayed, artistic awareness of the relevance of modern socio-political settings and a new potential role for art. That was to address the more complicated societal problems plaguing the young nation-state more directly. However, for a long time, a more thoughtful confrontation with the more fundamental intra-ethnic societal challenges was inhibited by the dominant interest in conceptual art and abstract art concerns by many renowned artists at the time.

As a result, the National Cultural Congress (NCC), which was held at the University of Malaya in 19171, was a direct result of the May 13 riots and was called by the National Operations Council, which was in power then (Abdullah, 2020). The National Culture Congress was viewed as a formal attempt to define Malaysian identity. The Iranian revolution of 1979 may have influenced Malaysia’s late 1970s revival of Islam. It was stated during this critical Congress that the country needed a shared national identity and culture to keep it united. Affirmative action for indigenous peoples was also established to be a requirement to address the racial and economic imbalances that persist.

After much negotiation and debate in Congress, it was concluded that the state had to establish the foundation of official national culture formally. From this, Malay fundamental values, cultural traditions, and the Malay language as the approved national language ought to serve as its foundation. This then functions as the overarching framework for developing a shared official national cultural identity. These resolutions were approved by Congress and delivered to the government for prompt implementation (Sharan and Legino, 2018). This significant choice had the effect of changing the cultural surroundings in which the country has ever since operated. More crucially, the government had now strengthened the dominance of the Malay nationalistic forces. The government had also developed a cultural vision that it politically defined. Malay-centered rhetoric and dominance would serve as the foundation for the mass narrative. As a result, the introduction of the Malay language into colleges and schools was accelerated, and a politically charged definition of national culture was now formally prescribed. It would be prioritized and followed at all official national ceremonies. Since then, the NCC which resulted to National Culture Policy has been in effect and has impacted the Malaysian visual artist and art scene.

Impact of The National Congress on The Visual Artists and The Art Scene

The National Culture Policy implementation, motivated by the NCC caused the Malaysian art scene and society to take a different course. Despite these early objections, artists started the challenging and painful process of re-evaluating their beliefs. They started changing how they saw numerous crucial issues relating to their identities and the Malay culture, race, language, nation, and state (Sharan and Legino, 2018). The definition of Malay tradition and its relationship to modernity were issues that Malaysians had to deal with. The visual arts started to generate works with interest in Islam and Malay culture.

Malay styles started to recur in the works of artists such as Tengku Sabri Tengku Ibrahim, Amron Omar, Raja Shahriman Raja Az Idin, Mad Anuar Ismail, and Jalaini Abu Hassan. To situate themselves within a bigger global Islamic ummah, artists like Zakaria A Wang, Sulaiman Hj Esa, Ahmad Khalid Yusof, Ponirin Am in, Hamdzun Haron, and Sharifah Zurich adopted a new perspective. Decorative art started to emerge at this time as well. Although these writings explicitly use Malay forms, it is possible that the fundamental idea originated in the Islamic religion. This group includes artists like Mohamed Najib Dawa, Fatimah Chik, Noraini Nasir, Siti Zainon Ismail, Khatijah Sanusi, Ruzaika Omar Basaree, and Mastura Abdul Rahman (Sharan and Legino, 2018). The decorative features of Malay textiles, such as carvings and batik, are heavily emphasized in their works. Ever since Malay and Islamic influences in their artwork have piqued the interest of mainstream Malay artists. Up until the late 1980s, these patterns appeared to be quite dominating. Despite the National Cultural Policy’s implementation, Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad rejected it in the 1990s, emphasizing a Malaysian identity for the nation rather than a Malay one.

Therefore, in the 1990s, Mahathir introduced Vision 2020, a new initiative for Malaysia’s continuing growth and modernization, marking a turning point. According to Goh (2018), this Vision’s goals are significantly more ambitious than the 1970 Rukunegara in terms of national and ethnic harmony. A united Malaysia with all of its citizens living in harmony and prosperity in an advanced society that values knowledge, economic strength, and dynamism and is motivated by the principles of compassion and tolerance was the goal of this thirty-year plan, which was intended to replace the National Economic Policy (NEP). The people in the new initiative, that is, Vision 2020 appear to have undergone a name change, giving rise to a new race or nation in which the Malays are no longer considered Malaysia’s most important ethnic group. The National Development Policy (NDP), which took the place of the NEP, allowed the government to continue implementing most of the NEP policies (Jafri and WMD, 2022). Although the Malay portion of the economy is more prominent, the government said it was still well below the thirty percent target.

Therefore, some physical facets of the Vision started to take shape in the 1990s. For instance, foreign investors were encouraged to participate in developing Cyberjaya, a Malaysian equivalent of Silicon Valley, and the Multimedia Infrastructure Components connecting Kuala Lumpur with the new “smart metropolis” built. Several contentious “mega” projects, including the Petronas Twin Tower, the Sepang-based Kuala Lumpur Airport, and the Formula One racetrack, were also completed during this decade (Connolly, 2022). Some of these initiatives were somewhat slowed down by the 1997 economic crisis, as were several other planned “mega” projects. Significant changes have occurred in Malaysia’s cultural landscape since the 1990s. Furthermore, educational, cultural, linguistic, and artistic realms have seen a startling transformation, particularly in terms of their pluralist viewpoints, images, and ideals. The diversity and multiculturalism of ethnic and cultural manifestations in dance, song, poetry, theater, and short stories have increased. Malaysia experienced the onset of globalization and cutting-edge technologies like the internet in the 1990s. Works about different lifestyles and non-Malay culture started to be showcased in the National Gallery of Malaysia (Khalefa et al., 2020). They joined the Young Contemporary Awards held by the National Gallery at least once each two years.

Additionally, the celebrations or lifestyles of various cultures including Chinese and India started to permeate the Malaysian art mainstream. For instance, artists like Liew Kung-Yu and his series “Chinese Festival” and Cheng Beng Festival,” artworks depicted Chinese culture. J. Anurendra, an Indian artist, also advanced themes from Indian culture. In his 1997 painting “Looking Forward,” he dedicated Hindus to enduring suffering during the Thaipusam festival to atone for their sins. East Malaysian artists like Kelvin Chap Kok Leong, Bayu Utomo Radjikin, and Shia Yih Ying repeat imagery and themes from tribes in Sarawak and Sabah. Even late-blooming artist Sylvia Lee Goh draws attention to the disappearing cultures of the Saba and Nyonya communities. Additionally, there was a trend toward artistic endeavors, particularly concerning topical concerns like environmentalism and consumerism. Some works may be perceived as more overtly challenging societal themes, including freedom of speech, human rights, social justice, and democracy in Malaysia (Sharan and Legino, 2018). As many Malaysian artists start to give up sculpture and painting in favor of embracing or incorporating novel strategies and media into their work, blending several arts disciplines has also impacted the direction of Malaysian art.

Furthermore, English usage was no longer viewed as a danger in literature. A new generation of writers was also rising alongside more experienced ones like K.S. Maniam, Lloyd Fernando, Krishen Jit, and Wong Phui Nam. Non-Malay artists like Leow Puay Tin, Rahel Joseph, and Charlene Rajendra employed English in their works, but so did Malay writers like Karim Raslan, Huzir Sulaiman, Rehman Rashid, Dina Zaman, and Amir Muhammad. They employed English as their favorite language. Saloma Lajos, the author of Pelangi Hari, won first place in the “New Malay Novel” competition, partially endorsed by GAPENA (Malay for Malaysian National Writers Association). She was praised for Pelangi Hari’s outstanding Bahasa Malaysia and decent English as evidence of her high intellectual achievement. According to Ker et al. (2020) the 1995 judges appear to have approved of English as a component of the “New Malay Novel.” The theatrical industry saw a change as well. Additionally, the 1990s witnessed a diversity in the various artistic styles and directions in modern English-language theatre, which included the work of the Instant Cafe Theatre, Five Arts Centre, Akshen, and Repertory. I want to emphasize how these groups’ members’ increasing ethnic variety encourages creativity and diversity as a potential alternative platform.

Malay/Islamic Centered Art and Post Modern Art

Introduction

In Malaysia, from the middle of the 1970s onward, there was a growth in Islamic awareness and policies that may have had more of an impact on arts and culture than the National Culture Congress. The advent of the Muslim Youth Movement of Malaysia (ABIM) and the Iranian Revolutionary in 1979 might be considered parallel developments of the Dakwah movement, which gave rise to this Islamic awareness. It might be said that Malay artists’ artistic practices in the 1970s and 1980s were significantly influenced by Islamic consciousness (Abdullah, 2018). Malay artists started using their interest in the Islamic religion and Malay culture as a means of expressing their identity throughout the 1970s and 1980s when the national culture was declared, and Islam also had a rebirth. This was particularly true of the Malay artists who were faculty or students at the ITM School of Art and Design. However, such aesthetic strategies for art have become less prevalent since the late 1980s and early 1990s. The significant transition from Malay/Islamic-centered art to a postmodern art method has been studied and placed as an indirect or direct result of the postmodern situation (Abdullah, 2020). This became important when Malaysian artists, who were a member of the country’s emerging middle class, started to advocate for some of the issues that affected their group rather than limiting their artistic pursuits to narrow ethnic lines.

The Shift to Postmodern Art

The theme alignments of the personal aesthetics and the constrained cultural interests of the Malays relative to Malay/Islamic-centered art started to wane with numerous artists’ broader adoption of postmodern artistic techniques. For instance, Malay artists started considering their place in the country’s larger historical, cultural, and social framework and the broader world. In addition to embracing postmodern artistic techniques like appropriation and the usage of multimedia in their works, Malay artists are now more liberal, and their thematic concerns are more global. These works promote values like rationalism, democracy, individualism, and secularism and show apprehension for civil rights, the ecosystem, and the rule of law ideals typically linked with middle class concerns (Khalefa et al., 2020). Moral and social transgressions, as well as problems with the environment and industrialization, are among the prevalent thematic subjects among these artists. Though many artists continue to draw inspiration from Malay history, values, culture, myths, and literature, the aesthetics, artistic forms, techniques, and sensitivities are somewhat different. Their paintings now incorporate subtle nuances on contemporary issues rather than being limited to the solely aesthetic aspect of such aspects.

Hamir Soib, for instance, created works with titles appropriate to his worries concerning the social and moral decay in the Malay community. “The Rempit” (Illegal Motorcycle Race), Haruan Makan Anak (Haruan Fish Eats it Babies), “A Board Game,” and “Telur Buaya” (Crocodile Egg) are some of the titles he has chosen for his works. These artworks act as a visual chronicle to convey his apprehensions about, what he perceives to be, a faltering society. Significantly, Bayu Utomo’s works from the 1990s expose us to the modern problems that plague a particular group of these Malay urban people. His realistic depiction, combined with his use of various media, forces us to face the realities of single mothers, abused children, abandoned children, drug addiction, and other issues urban Malay youngsters face (Abdullah, 2018). Zulkifli Yusof also had criticism for how some Malay society members lived. His series brought attention to societal problems and controversial topics in Malay culture. Hamir Soil and Zulkifli Yusuf’s works, in contrast to Malay and Islamic art that encouraged viewers to appreciate the visual features of the artworks in a welcoming gallery atmosphere, are highly upsetting and upsetting to the general population.

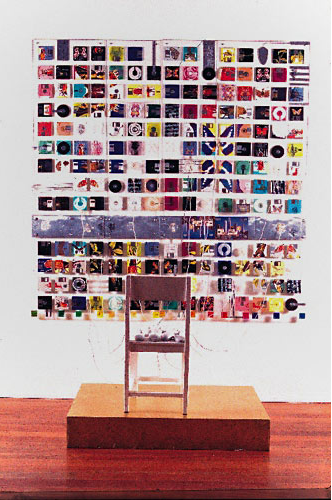

Furthermore, some of Malay artists have started to address themes related to urbanization and the environment due to the rapid growth and development over the past thirty years. For instance, Ahmad Shukri’s “Insect Diskette” (1997) (figure 1) is a mixed-media installation of more than 200 computer diskettes.

These are shown as butterflies, insects, palm trees, and other “specimens” and are organized in a square over four plexiglass surfaces. He supports harmonizing technology and nature rather than criticizing or rejecting the technologies that modernization and development have brought.

However, it may be asserted that their artistic styles, technique, aesthetic principles, and sensitivities are distinct from previous works of Malay/Islamic-centered art. Several works by Malay artists appear to be still influenced by Malay cultural norms and forms. One such instance might be the sculpture of Raja Shahriman Raja Aziddin. His sculptures, like those in the “GerakTempur Series” (1996), are substantial because they carefully depict human anatomy while maintaining the characters’ romantic bersilat positions. Raja Shahriman’s sculptures of the Malay silat warrior—a type of military art practiced in the Malay Archipelago have been depersonalized and dehumanized (Abdullah, 2018). Additionally, they are devoid of all pretense, giving them the appearance of strength even though the movements appear gentle and soft just before the figure strikes. Raja Shahriman continuously pushes the limits of his ability to mold metal in another collection of sculptures, the “Langkah Hulubalang Series.” Each sculpture in “Langkah Hulubalang” has a distinct distinctive personality, but each form also exudes grace and beauty. These sculptures are unquestionably carefully thought out and exhibit accuracy in shape and balance.

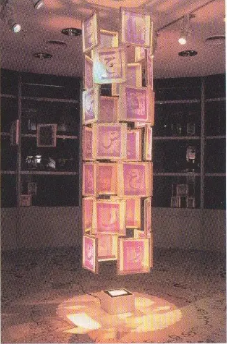

Moreover, Malay artists started investigating more difficult deconstructionist issues, like opposing official political and historical narratives. For instance, various issues mentioned in the media inspire artistic interpretation and perspective. In 1999, HamirSoib created the installation piece “Jawi Series” (Figure 2), which challenges the idea that the Arabic alphabets used to write the Malay language or Jawi express Malay identity.

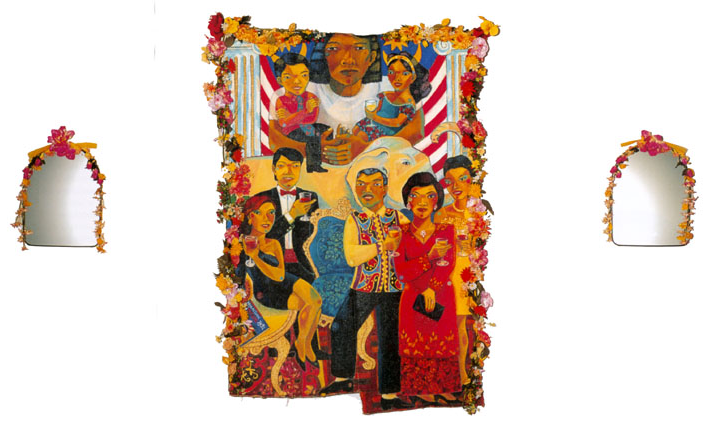

The clearest example of this viewpoint is provided by Wong Hoy Cheong’s “The Nouveau Riche, the Elephant, the Foreign Maid, or the Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie” (1991) (Fig 3). It can be said that Wong Hoy Cheong reflects the naive consumerism of the multiethnic Malaysian middle class in this mixed-media work. The piece’s left and right sides are mirrors that portray the spectators as a component of the artwork, while the center section includes a canvas depicting groups of persons at a cocktail party (Abdullah, 2018). The characters that the artist exhibited at this event crossed racial barriers while grasping drinks in their hands. Drinks were in the grasp of the woman wearing a baju kurung and the man wearing a batik shirt. The Chinese man is wearing a suit and tie, and her female companion, seated on the left with her legs crossed, is also holding up their drinks. Another couple is seated in the background, and the woman in the green outfit is seen holding her drink. A picture of a man (perhaps the artist) is hidden behind these scenes, flanked by Doric columns, with the Malaysian flag flying at his right and left.

The piece serves as a reminder that the middle class of Malaysia has now materialized and united, motivated by aspirations for lifestyle, wealth, and consumerism rather than being divided along racial lines.

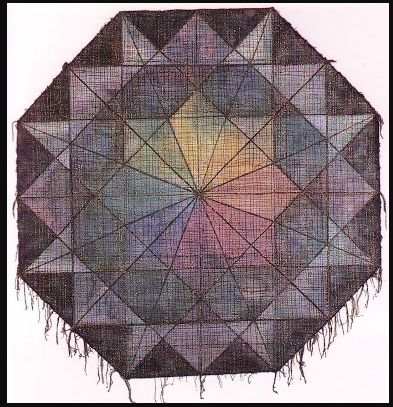

As contemporary artists, they were not limited to conventional mediums but instead incorporated Islamic aesthetics or ideology into their work. For instance, Sulaiman Esa’s Nurani series (Figure. 4) is an artistic exploration of conventional Islamic arabesque design in search of Islamic aesthetics. Islamic spiritualism is deeply entwined with the experience of synchronization and archetypal reality in work through the arabesque, which reflects the One (Allah the Almighty) and the idea of tawhid, or unity.

Most of the time, Islamic art flourished in Malaysia since the artists who avoided metaphorical painting did so because they sympathized with the Avant-abstraction garde rather than because doing so was forbidden by Islam. TK Sabapathy, an art critic, asserts that “work portraying the global Islamic revisionism in the 1980s has either allied itself with inclinations in Abstract Expressionism or established affinity with ornamental art.

Noting that the Islamization of modern art in Malaysia was not simply the artist’s responsibility is equally crucial. Also important were the choices made by the curators. The choice of creators and pieces for galleries and exhibitions frequently reflected public perceptions of contemporary Islamic art. As a result, these exhibits and works of art were quickly interpreted as “Islamic.” It should be emphasized that the New Economic Policy (NEP), culture policy, and Islamization policies were all announced during the nation’s nationalist era, which unavoidably resulted in a nationalistic agenda being reframed in art (Goh, 2018). Despite the nation’s mixed makeup, this set of policies maintained the state-endorsed national identity centered on the hegemony of Malay culture.

As a result, during the 1990s, there was a significant paradigm shift in how Malaysian artists approached their work, as detailed in this study. Malay artists during the 1990s who embraced a postmodern perspective were outwards focused and confronted continuing social and political challenges, in contrast to Malay/Islamic-centered art, which is inwardly and artistically focused. Their thematic approach to their work emphasizes how they are dependent on and inextricably a part of Malaysian society rather than working or living in a vacuum (Abdullah, 2018). These art pieces need not be attractive, symbolic, or realistic, in contrast to those concerned with Malay or Islamic ideals. Images from high and low cultures, as well as from traditional and modern life, are combined. Innovative media and method use defy strict formal and structural rules, such as collage, photographic imaging, montage, and digital manipulation.

As a result, Malaysian artists’ eyes are opened beyond the constrained understanding of art and its function in society through the use of collisions, fragmentation, and collage. It might be argued that using the word “postmodern condition” to describe this transition in Malaysian art development implies that this new paradigm has virtually nothing to do with the rupture of the earlier stages of the modern period. The term “postmodern situation,” as it is used here, refers to the cultural condition that has arisen due to Malaysia’s entry into the modern economy, which was facilitated by the government through NDP and NEP, particularly among the emerging Malaysian middle class. The works by the artists previously mentioned representing the cultural conditions, which are not only fractured but, most significantly, the Malay middle class has been tugged in several ways, creating a confusing and even contradictory culture.

To summarize, during the late 1970s and early 1980s, external economic and social forces also influenced Malaysian art. For instance, a new Malay middle class also emerged as a result of the economic success the Malays achieved through the NEP. Joel S. Kahn claims that the NEP and the rise of the new Malay middle class aided the development of Malaysian identity by reinforcing Malay culture. Given the resurgence of Islam during the period, it was not surprising that some artists used their interest in Islam to express a sense of national identity via their work.

National Identity and Art Production

Introduction

The development of information and communication technologies has brought many changes to every aspect of life, be it social, economic, or political conditions, which will undoubtedly shape the thinking and behavior of people. The notion of the global or universal village, first proposed in 1960, envisions a limitless future for the interacting world due to the advancement of information technology (Abdullah and Elham, 2019). Since Malaysia is a multiethnic country with a diverse range of cultures and ways of life, Malaysia has always been required to deal with the challenges of nation-building as well as the ongoing development of technology. A person’s choice of art may reveal a lot about their identity. A person’s mentality, emotions, and concerns heavily influence their choice of art. The values of that society’s objects, beliefs, and practises are reflected in and upheld by artwork.

Since the 1990s, Malaysian art has expanded in terms of method, theme, subject, and medium. Not just within the context of postmodernism but also in terms of the particular social and cultural transformations the nation has seen since the introduction of the NEP, as well as the follow-up New Development Policy (NDP), Malaysian art trends are frequently studied. As a result, discussions of the transition from Malay/Islamic-centered to post-modern art during the 1990s frequently focus on Malaysia’s emerging middle class, which the NEP and NDP helped to create, particularly among Malay Community.

The evolving artistic perspectives in art since the 1990s mirror the structural reshaping and sensation of the “novel” middle-class individuals in Malaysia that these artists relate to. While the artistic preferences of Malay artists in the late 1970s and early 1980s have been grounded in Malay or Islamic aesthetics or what might be considered “Malay/Islamic-centred art,” Malay artists started using their enthusiasm in Malay heritage with the Islamic faith as a means of expressing cultural identity throughout the 1970s and 1980s when the national culture was declared, and Islam also had a rebirth. Post-modern art, on the other hand, has inspired contemporary artists to address a variety of facets of the post-colonized and globalized world.

The Malays that make up the “novel” middle class in Malaysia have undergone significant social and cultural upheaval, which has been referred to as a “post-modern situation.” The phrase describes how Malay culture appears to be divided and grounded in various cultural elements, including tradition, Islamic principles, and contemporary or liberal ideas. This is the outcome of the extreme modernization initiatives placed on them since NEP, which have caused significant cultural and social changes. Examining numerous individual works by modern artists reveals how they frequently question location and national identity ideas.

It is not surprising that Malaysian artists are interested in the idea of identification because they have been asking about important issues and starting identity searches ever since the NCC. These visual representations of “national” identity in the context of multiracial Malaysia have just recently been called into question or brought up, as identity is not a fixed notion that can be debated by everybody. It is not surprising that Malaysian artists can produce work that deconstructs Malaysians’ long-standing obsession with race and identity thanks to the post-modern understanding of identity as an unpredictable reality. In Malaysia, the question of identity is deeply embedded in the concept of national identity. This is also unsurprising given that the emerging Malaysian middle class has challenged racial indicators or limits, particularly as relations between the three main races have improved. As an attempt to engage and explore the colonial power represented in artwork created by diverse artists like Yee I-Lann, many modern artists started to integrate certain motifs found in the preserved pictures of history into their pieces.

Analysis of Yee I-Lann Artwork

Contemporary Malaysian artist Yee I-Lann uses photomontage, collage, cinema, communal weaving, commonplace materials, and a multifaceted visual language derived from historical allusions and contemporary culture in her pieces. To create an aesthetic appearance, photomontage merges many pictures. The views and perceptions of such pictures can vary or be subverted as a result of the combination of these images. Her work explores the effects of historical memory on contemporary social interaction by looking at South Asia’s power structures, imperialism, and western imperialism. Yee I-Lann examines her origins and allegorizes the tales she was raised on in pieces like “Sulu Stories.”

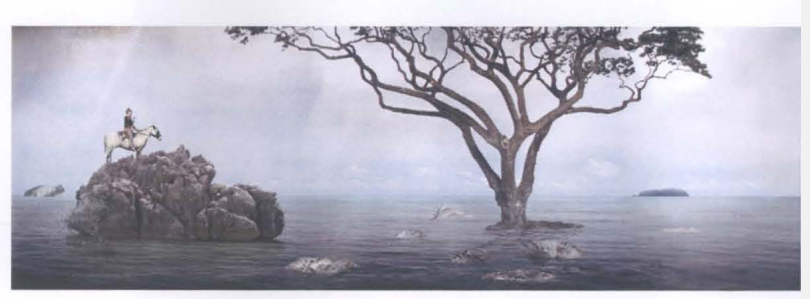

With the aid of such early recollections and archives of data pertaining to Sulu, she creates works that transport the spectator to numerous natural views, the seas, the islands, and the sky. The visuals related to her narrative are juxtaposed in her paintings. For instance, the enormous tree in “The Archipelago” (2005) (See appendix 1) was recorded in the Fallen American Soldier Cemetery in Manila and is a Caesalpiniaceous tree that was brought to Asia from South America. Sultan Jamalul Kiram II, the last Sulu sultan to rule, was represented by the soldier on horseback. To create the illusion of islands in the foreground, the artist meticulously shoots and digitally alters photos of the fragments of coral and stone collected on the coasts of Sabah and Palawan. The ability to readily edit photographs is made possible by the development of computer technology, increasing the potential for an appropriation approach. The use of appropriation and allegory in artwork has evolved since the nineties. Works are getting increasingly complicated, personal, and open to numerous interpretations, as seen by Yee l-“The Lan’s Archipelago.”

It is important to note that while the “Malaysian Series “does not maintain his interest in postmodernism, the post-modern tactics and the topics presented in it mirror the prevalent worries of the Malaysian middle class regarding identity, culture, and issues. Similarly, two decades later, Yee I-“Malaysiana Lan’s Series” presents the spectator with a variety of replicated pictures. Other artists have since picked up these ideas ” (2002). The vast majority of studio photos were created from a sparse collection of picture negatives from Malacca’s Packard Studio, which was active between 1977 and 1982.

Her art serves as a reflection that racial affinity is essentially a cultural, social, and historical fabrication, in contrast to Piyadasa’s “Malaysian Series,” but also that notwithstanding disparities in skin tone, appearance, and other physical characteristics, we are all still humans. The art series makes us consider who we are in relation to Malaysian society at large. The piece challenges us to reflect on our lives from childhood through maturity and analyze our place in a wider social and cultural framework. The piece explores Malaysia’s national survey of the three main races from the perspective of Yee I-“Malaysiana Lan’s Series” (2002). A number of the persons in her collections of images couldn’t even immediately be identified as Chinese, Malay, or Indian, indicating that racial distinctions are not always distinct and well-defined.

Additionally, it should be mentioned that Yee 1-Lan and Simryn Gill are two artists that are quite knowledgeable about current events in the global art scene. They have both collaborated across international lines and taken part in international art shows. As a result, they can comprehend and handle the subject of race in a highly ambiguous and open-ended manner, in contrast to other artists who seem to deal with racial concerns more directly, as in Shia Yih Yiing’s “Vessels of Art, What is Your Equipment?” (2006). Shia Yih-series Yiing appears to be more upbeat and in line with the government’s ideal of a united Malaysia, notwithstanding the diverse races and religions of its population, than the artworks of Yee 1-Lan and Simryn Gill.

On the other hand, Yee I-work Lann’s at the International Contemporary Art Fair (Arco) not only shows her talent to transform kitsch and everyday objects into art pieces but also serves as a commentary on the issue of commercialization in contemporary society. She uses billboard fabrics to create a variety of bags, which represents her interest in advertising, advertising, and capitalism. This might appear on the tote bags with pictures of two Asian kids with the phrase “Buy Me” in a monologue. Additionally, some bags have corporate logos and popular brands, including Coca-Cola, Pampers, MTV, Nescafe, Ultraman, and CNN. Her sculpture consisted of 85 bags that were among the most affordable works of art in the show’s for sale, each costing 208 Euros. Malaysian artists have also addressed other important subjects, such as their reactions to the country’s unchecked growth and increasing urbanization.

Analysis of Kok Yew Puah

As numerous artists reside in urban or suburban regions, the issues brought about by growing urbanization and the state of the environment and animals are also of concern to these artists. Globalization has altered our urban environment, whether favourably or negatively. Kok Yew Puah was a painter who depicted the surroundings of the city in his works. Before becoming renowned as a figurative painter, he was recognized for his daring, hard-edge silk-screen prints (Yong, B. and Joseph, 2021). He decided to depict his kids and other friends in Klang, Malaysia, by placing them in a few specific metropolitan landscapes. He didn’t paint portraits or landscape views; instead, he captured these vistas with his “camera lens” and painted them voyeuristically through the eyes of a traveller. His huge works include intricate detailing and vibrant Malaysian hues. Contrasted with the vibrant hues of youth fashions, signs, vehicles, freeways, and perhaps even vibrant pre-war structures are structural colours and stark blue sky. His use of clashing colours makes his work stand out and suggests the stunning and vibrant character of modern life and surroundings.

Whereas Kok Yew Puah portrays a hopeful view of urban lifestyle in his satisfied multiracial individuals and vibrant surroundings of Klang, Wong Hoy Cheong depicts a different side of urban reality through juxtaposing urban settings in Selangor. By tracking the evolution of Kok Yew Puah’s practice and ideas via his artworks, articles, discussions, publications, and talks with individuals who encountered him regarding his background, personality, and preferences, the exhibit “Portrait of a Malaysian Artist” considers Kok Yew Puah’s artwork.

Puah’s self-portraits, which are frequently amusing and created in various “postures,” offer some intriguing notions about what his “artistic identity” may entail. He is viewed in time as a futurist, an artist, a spouse, a parent, a colleague, and an educator from the viewpoints of others. Puah often used himself, his spouse, their kids, and his acquaintances as inspiration for his human portraiture in his works (Kamal, 2022). By utilizing recognizable visual signals in the surroundings, architecture, attire, and “props” they carry, they are recognized as Malaysians. They do constitute a bigger, more intimate portrayal of Malaysia that the artist has created based on his observations of life in his home as it underwent industrialization (Kamal, 2022). Concerns about environmental harm, the effects of fast growth, especially on millennials, and a growing cultural and historical gap are all expressed in the images.

Art and Young Generation

In general, the political and social background of this society’s art lets the younger generations speak out more regarding taboo Asian subjects. Art has an impact on society by transforming attitudes, imparting ideals, and interpreting events across place and time. According to research, art has an impact on one’s core self. The arts—including painting, sculptures, music, writing, and other forms—are sometimes seen as the storehouse of a society’s cultural memory. Someone who comprehends an artwork perfects it (Mat et al., 2020). People need to have a thorough understanding of the history of art to appreciate it.

Once a community is “art literate,” it will be capable of learning about, understanding, and enjoying art more thoroughly. Artistic pursuits are inextricably linked to human community interaction, whether for emotional or practical reasons. A civilization that values art will always value the contributions of its forebears and may develop a passion for both its own culture and that of other people. People who enjoy art do not just focus on regional or local works; they might also develop an appreciation for global or foreign works (modern art) (Mat et al., 2020). The outcome of this openness to information may improve the national spirit and knowledge while also fostering Malaysian identity and self-assurance. Malaysian artwork may enhance the stature of regional art, which defines the culture of the country, to a global scale by combining the enjoyment of local and global art (Mat et al., 2020). By valuing art to its fullest, Malaysia will develop a country with a powerful national identity that can lead other countries in navigating the globalization period.

Moreover, the past is revealed through the artwork of the past. One may discover information about the civilization that created a piece of art by examining the symbols, colours, and materials used in it. An individual will be able to understand what was significant to these people and how they wanted to be remembered after deciphering the symbolism in these photos. Additionally, individuals may contrast artwork, which offers many viewpoints and provides them with a well-rounded viewpoint on things, individuals, and circumstances. One can travel back and experience a timespan other than the present by closely examining works of modern art, including pieces from the past and the present (Hylton, Malley, and Ironson, 2019). Analyzing earlier works of art and contrasting them with the current helps define a person or group of individuals as a society or a community. People learn from and are inspired by what has accomplished in the past, which influences how they think, feel, and perceive the world around them.

In addition, studies demonstrate that involvement in the arts may help teenagers acquire a variety of beneficial abilities and talents that are seen favourably by bosses and employers, including perseverance, teamwork, inventive problem-solving, motivation, and tenacity. Additionally, studies show that exposure to the arts can enhance a teen’s self-confidence and academic achievement (Winsler et al., 2020). Young people from low socioeconomic levels who have a background of intense artistic activity outperform those who have less intense artistic involvement in terms of academic performance. Those who are deeply involved in the arts have notably greater professional goals than do students with no arts training.

Conclusion

The material reviewed for this dissertation relates to the topic of modern and postmodern Malaysian art. These articles made a significant contribution to the area of Malaysian art in several ways, including showcasing the aesthetics of Malaysian Islamic artworks and emphasizing the value of these works in enhancing regional identity. Although the NEP is a prominent example of affirmative action, it also represents a turning point in Malaysian politics, the economy, and social relations, resulting in the country’s society becoming increasingly homogenized based on race. This has resulted to the new Malaysian art scene as its’ artwork presents a diverse racial and cultural identity image. Some artists’ artistic strategies have evolved and grown in various ways since the 1990s, as was evident. Their interaction on a global scale was made possible by various electronic networks, as well as their involvement in international art exhibitions like Documenta, the Sydney Biennale, the Venice Biennale, and the Fukuoka Asian Art Show.

Additionally, Malaysia, which is turning 59, is dealing with identity problems brought on by the expansion of political Malay-Islamic and Islam domination. As more of its residents ponder the most fundamental question: “What constitutes a Malaysian national identity and what exactly is Malaysia?” national integration and national identity, a crucial programme in every Southeast Asia nation, appear to be stagnating in Malaysia. This may seem like an unusual question to raise after 60 years of nation-building, but it is important to Malaysian society today and is based on the two most divisive topics in terms of national integration and identity.

Due to Malay leaders’ view of religion as the best effective political tool, political Islam has dramatically increased over the past 20 years. This has led to a vociferous Islamic minority pushing for Malaysia to be recognized as an Islamic nation and for Islam to be formally proclaimed the established religion in the Legislation. Nevertheless, non-Islamic organizations already face several limitations in their practice, and Malaysian law officially considers evangelizing to Muslims to be a crime. Several have come to the conclusion that the government is working to turn Malaysia into a Malay-Islamic state as a result of the political difficulties surrounding the emergence of political Islam. Unfortunately, additional restrictions to govern individual Muslim behaviour, such as clothing requirements, have resulted from using socio-political Islam to increasingly split the community and socially subjugate non-Muslims in Malaysia. This is because Islamists want to regulate non-Islamic religions there. Consequently, it is impossible to distinguish national identity and geopolitics from Malaysian artwork.

As is clear, there are a variety of works of art, including traditional works that are reasonable, traditional pieces that are entirely impacted by external components (modern), and contemporary works that are entirely impacted by cultural aspects. The evolution of art in Malaysia is a result of the society’s and artists’ willingness to accommodate and analyze both traditional and contemporary forms of expression. Malaysia is now a nation rich in diverse types of artworks as a consequence of the society’s and artists’ open-mindedness. When art is fully appreciated, Malaysia will develop into a country with a strong sense of self that can lead the rest of the world in coping with the globalization period. Since the early l990s, a more socially conscious artist has arisen in this country, using controversial, aggressive, and re-questioning tactics in his creativity. However, future research must look at how the influence of postmodernism may be reconciled with the distinctiveness of Islamic Art. Additionally, future studies should establish how and where postmodernism impacts the aspects of Islamic art in Malaysia to assess the extent of its influence on Malaysian Islamic art. To maintain Islamic art relevant in the modern world, it is also essential to investigate and discuss other thinkers’ perspectives and critique the artworks.

Reference List

Abdullah, S. and Elham, S.K., 2019. Culture and identity in selected new media artworks in malaysia 1993-2007. Universiti Sains Malaysia.

Abdullah, S., 2018. Malaysian art since 1990s: Postmodern situation. Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka.

Abdullah, S., 2020. The 1980s as (an Attempt in) the decolonialization of malaysian Art. Southeast of Now: Directions in Contemporary and Modern Art in Asia

Connolly, C., 2022. Megapolitan explosions: Reworking urban and regional metabolisms. In Political Ecologies of Landscape (pp. 38-56). Bristol University Press.

El Refaie, E., 2019. Visual metaphor and embodiment in graphic illness narratives. Oxford University Press, USA.

Goh, B.L., 2018. Modern dreams. In Modern Dreams. Cornell University Press.

Hylton, E., Malley, A. and Ironson, G., 2019. Improvements in adolescent mental health and positive affect using creative arts therapy after a school shooting: A pilot study. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 65, p.101586.

Jafri, A.N. and WMD, W.S.A., 2022. Reflections of national cultural elements in young contemporary award artworks.

Kamal, A., 2022. Kok Yew Puah: A legacy of the past takes presence, The Vibes. Web.

Ker, Y., Chotpradit, T., O’Connor, S.J., Soon, S., Abdullah, S., Nelson, R., Campos, P.F., Taylor, N.A., Mahamood, M., Chua, L. and Miksic, J.N., 2020. Teaching the history of modern and contemporary art of Southeast Asia. Southeast of Now: Directions in Contemporary and Modern Art in Asia, 4(1), pp.101-203.

Khalefa, E.Y., Hashim, M.N.B., Othman, A.J. and Zainol, S., 2020. Post-modernism and malaysian islamic art: A review of literature. Sarjana

Lee, H. A., 2022. Malaysia’s New Economic Policy: Fifty Years of Polarization and Impasse. Southeast Asian Studies, 11(2), 299-329.

Mamat, N., Hashim, A., Razalli, A., & Awang, M., 2022. Multicultural Pedagogy: Strengthening Social Interaction Among Multi-Ethnic Pre-School Children. The New Educational Review, 67(1), 56-67.

Mat, I., Rahman, M.B.A., Abd Arif, H. and Mokhtar, E., 2020. AN APPRECIATION OF ART IN MALAYSIA: THE PROBLEMS AND BENEFITS IN SOCIETY. PalArch’s Journal of Archaeology of Egypt/Egyptology, 17(8), pp.414-421.

Nordin, A. B., Alias, N., & Siraj, S., 2018. National integration in multicultural school setting in Malaysia. MOJES: Malaysian Online Journal of Educational Sciences, 1(1), 20-29.

Sharan, N.I.M. and Legino, R., 2018. Printmaking artworks in malaysia that impacted after the national cultural congress in 1971. Advanced Science Letters, 24(10), pp.7027-7029.

Winsler, A., Gara, T.V., Alegrado, A., Castro, S. and Tavassolie, T., 2020. Selection into, and academic benefits from, arts-related courses in middle school among low-income, ethnically diverse youth. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 14(4), p.415.

Yong, B. and Joseph, R., 2021 Kok Yew Puah Portrait of a Malaysian artist, ILHAM. Web.

Appendices

Appendix 1