Industry Profile

The analyzed market sector is the wine industry in New Zealand. According to Euromonitor International (2020), in 2019, total volume sales increased by 1%, reaching 103 million litters. Concerning the sales performance of wine, the total volume growth within the last decade is 0.5% (Euromonitor International, 2020). The industry is marked by intense competition within several multinational companies and local wineries producing primal beverages and focusing on organic production (Euromonitor International, 2020). Firms compete on a global scale, prioritizing export in Asia and America.

At present, key customers are still represented by citizens as most of the wine is consumed by people in restaurants and bars. However, the COVID-19 pandemic has adjusted consumer behavior; people prefer to purchase beverages and drink them at home due to lockdowns (New Zealand Winegrowers, 2020). Moreover, as the industry is currently developing wine tourism, many customers are defined as enthusiasts, travellers, and specialists in agricultural and wine-producing (New Zealand Winegrowers, 2020). Competitors differentiate from one another mainly because of business approaches, such as affordable wine offers and various beverages; however, there is a common feature – sustainability initiatives.

Competitor Profiles

Complete a table of key competitors

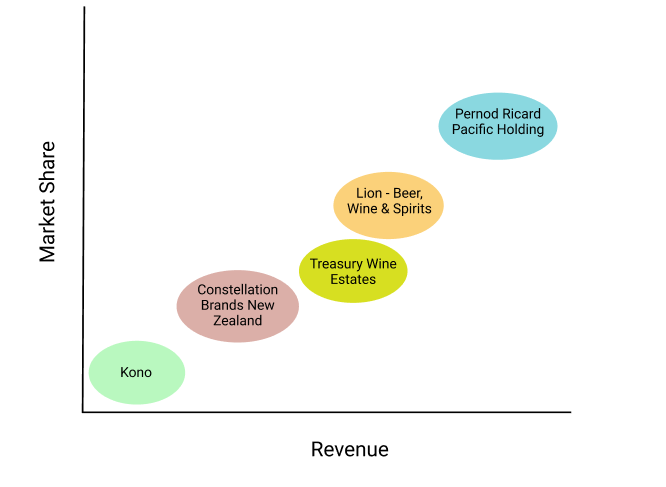

Complete a Strategic Group Map

Summarising key aspects of the industry from

New Zealand’s wine industry is characterized by intense global competition and significant market actors. Reliable to industry structure, the leading organization remains Pernod Ricard Pacific Holding. The total volume share is characterized by an upward trend in 2019; therefore, it maintains its position in the wine industry (Euromonitor International, 2020). It keeps a strong position due to implementing several innovations in the wine industry, such as the launch of low-strength variants in 2019 (Euromonitor International, 2020). The other player is Lion – Beer, Wine & Spirits (NZ), retaining the second rank. The company defines its profit by a comprehensive product portfolio with mainstream brands and strong distribution (Euromonitor International, 2020). Kono case represents the niche wine winemakers, being a Māori iwi-owned beverage business (Our Story, n.d.). Their business model focuses on Māori heritage and following traditions (Emen, n.d.). Despite the growing number of shareholders and customers, such wine producers remain a small portion of New Zealand’s overall production (Emen, n.d.). Overall, the industry structure is prevailed by global companies, adapting its business in the New Zealand environment.

Concerning the main factors that affect the economic performance of the companies are sustainability and wine tourism. As long as most stakeholders recognize sustainability as an essential factor, the brand’s perception in society can be a positive and conscious vision (Baird et al., 2018). Thus, it leads to boosted sales and brand loyalty (Baird et al., 2018). After reviewing the market players’ multiple annual reports, it can be concluded that the large share of companies’ policies concerns environmental and agricultural initiatives.

Industry Analysis (Porter’s 5 Forces)

The New Zealand wine industry is fragmented, consisting of various actors. The threat of new entrants into the industry is medium as the impact of new applicants on profits in the sector is minimal (Hanson et al., 2017). However, the number of small niche wine producers is growing (Euromonitor International, 2020). The latter do not have an established supply chain network and reputation, so these new wineries’ threat is considered mediocre due to the insufficient wine-producing practices and the reputation (Euromonitor International, 2020).

The power of buyers intensifies competition due to the imposition of higher requirements for the quality of goods, for the level of service. Higher standards for the wine force manufacturers in the industry improve the quality of the product produced by increasing costs such as higher quality raw materials and, consequently, reducing their profit level (Lee-Jones, 2020). The bargaining power of suppliers is determined to be high in terms of the wine industry. According to the New Zealand Winegrowers (2020), it is determined that winegrape supply amounted to 4.57 million tons in 2020 while the total production of wines was 329 million. Therefore, there is a shortage of supply in winegrapes, showing that supplier’s bargaining power is high. The price of wine grapes grew from 2017 to 2020 due to a lack of supply (New Zealand Winegrowers, 2020). Overall, the bargaining power of suppliers for the New Zealand wine industry is robust.

Concerning the power of substitutes, the data show that beer and ciders become customers’ favourable choices and the fastest-growing products within the alcohol industry. While the current year growth of wine estimates 0.5, the cider shows 6.0, reflecting 12.8% of the compound annual growth rate (CAGR) (Alcoholic Drinks in New Zealand, 2020). Beer figures are 1.4 of the current year’s growth and 1% of CAGR (Alcoholic Drinks in New Zealand, 2020). Thus, beer and ciders are highly threatened to wine as a substitute (Alcoholic Drinks in New Zealand, 2020). Concerning competitive rivalry, the New Zealand market is characterized by the winemakers owned by TNC, such as Pernod Ricard (Euromonitor International, 2020). At the same time, the number of small niche actors is increasing with the product quality as a market advantage.

Driving Forces (From PEST+/PESTLE)

Choose the most influential 2-3 trends, and use these to form a driving forces analysis: The first influential trend is the growing interest in organic wine production. According to Organic Winegrowing (n.d.), grapes grown without chemicals provide organic wines with a brighter taste, more nutrients and fewer sulphites. The organic status is assigned only to those vineyards located in an ecologically clean area with soil free from chemicals (Organic Winegrowing, n.d.). It is allowed to use only natural fertilizers such as the remains of cut weeds, ash (Organic Winegrowing, n.d.). New Zealand is prosperous in organic and biodynamic winemaking and aims to produce all wines produced in this way by 2025. Such a trend reflects the green initiatives and society’s values on ecological preservation and a healthy lifestyle.

Another trend that affects the wine industry significantly is wine tourism. According to New Zealand Winegrowers (2020), such activity is prioritized by multiple country’s wineries. Such trips include “cellar door visits, restaurants, winery and vineyard tours, and accommodation” (New Zealand Winegrowers, 2020, p. 8). Whereas it benefits the wineries in terms of economic performance, it is part of its government policy to attract funds and capital; the Sale and Supply of Alcohol Act should support wine tourism. In COVID-19 circumstances, the investments are the same as in 2019 (Impact of COVID-19, n. d.). The forecasts claim that wine tourism will be at the same level in the short-term in 2022 (Impact of COVID-19, n. d.). Therefore, the trend may be advantageous for all stakeholders and adjust the wine industry, bringing more clients worldwide after opening borders.

Strategic Issues: Opportunities & Threats

Opportunities

Regarding competitor profiles, almost all the new wine production is performed by multinational beverage businesses such as Pernod Ricard (Lee-Jones, 2020). Due to the COVID-19 pandemic outbreak outcomes, the internal policy has resulted in the delay of new plantings in 2020 (Lee-Jones, 2020). Thus, the active market actors are limited, which allows the government to persist with such policies until the situation is stable (Lee-Jones, 2020). The possible opportunity that in 2021, improved grapevine farming would lead to a greater overall average yield per hectare (Lee-Jones, 2020). According to Lee-Jones, 2020, New Zealand wine exporters emphasize high-quality and high-price point production. Consequently, it presents more chances to increase the export rate and achieve profits.

Another strategic issue is ecological intentions; the industry should consider effective production in terms of fertilizers. According to New Zealand Winegrowers (2020), almost all New Zealand vineyards are certified by Sustainable Winegrowing New Zealand (SWNZ) (Baird et al., 2018). The SWNZ program is built on guidelines issued by the Organization for Vine and Wine International (OIV) (Baird et al., 2018). It provides models of best practice ecology in vineyards and wineries (Baird et al., 2018). The standards cover biodiversity, air, water, soil, energy, plant protection, waste management and social engagement (Baird et al., 2018). Compliance with standards will help the wine industry to maintain its reputation.

Threats

Despite several valuable points, there are also risks mainly connected with the pandemic consequences. For instance, as the wine industry in New Zealand intends to export its production and the consumer demand abroad is growing, the uncertainty in 2020 has affected wine consumption among the citizens (Lee-Jones, 2020). It has shifted towards purchasing beverages at supermarkets and off-license premises to drink at home. Therefore clients’ spending on dining out are reduced (Lee-Jones, 2020). As part of the wineries offer their productions only in the restaurant and bar, they should change the strategy to meet stakeholders’ expectations, selling wine to wineries with supermarkets and off-license supply channels (Lee-Jones, 2020). Hence, the companies need to reconsider their selling policies.

Another threat is the declining wine tourism business in New Zealand due to the COVID-19 pandemic outbreak. The country’s border may remain closed for most of 2021 (New Zealand Winegrowers, 2020). As nearly 800 thousand cellar door guests visited New Zealand in 2019, the decreased number might lead to the industry’s economic failure. Nevertheless, the winemakers suggested developing a new online marketplace to sell premium wines directly to overseas buyers (New Zealand Winegrowers, 2020). This initiative may enhance business in the international market as other states are interested in limited-production wines.

References

Alcoholic Drinks in New Zealand (2020). Passport. Web.

Baird, T., Hall, C. M., & Castka, P. (2018). New Zealand winegrowers attitudes and behaviours towards wine tourism and sustainable winegrowing. Sustainability, 10(3), 797.

Constellation Brand. (2020). Annual Report.

Emen, J. (n.d.). New Zealand’s First Māori-Owned and -Operated Winery Has Global Distribution and a 500-Year Plan. VinePair.

Euromonitor International. (2020). Wine in New Zealand: Country report. Web.

Hanson, D., Hitt, M. A., Ireland, R. D., & Hoskisson, R. E. (2017). Strategic Management: Competitiveness and Globalisation (6th ed.). Cengage.

Impact of COVID-19 on Wine Tourism of New Zealand (n.d.). WineTourism.Com.

Kono NZ LP (2020). Dun & Bradstreet. Web.

Lee-Jones, D. (2020). New Zealand Wine Sector Report 2020. United States Department of Agriculture.

Lion – Beer, Wine & Spirits (2020). Dun & Bradstreet. Web.

Ministry for the Environment. (2019). Environment Aotearoa 2019 Summary.

New Zealand Winegrowers. (2020). Annual Report. Web.

Organic Winegrowing (n.d.). New Zealand Wine.

Our Story (n.d.). Kono.

Pernod Ricard. (2020). Annual Report.

Treasury Wine Estates. (2020). Annual Report.