Introduction

Countries with large endowments of oil often suffer from the harsh consequences of the resource curse. The case of Venezuela demonstrates that it is extremely hard to escape oil’s harmful influence, especially under conditions of immense oil revenues enjoyed by the country for more than a decade. With the end of the last cycle of high oil prices in 2014, it became clear that the Venezuelan government has not made adequate steps to prepare the country’s economy to function in the new economic environment (Columbia SIPA, 2015). Moreover, even before the drop in oil prices, Venezuela could not boast a stunning economic performance: its GDP per capita growth was one of the worst in the entire region (Columbia SIPA, 2015).

The aim of this paper is to explore the connection between dependency on oil and the current economic crisis in Venezuela. It will argue that rent-seeking, the Dutch disease, and the weakening of democratic institutions are the main reasons for oil resources being a curse instead of a blessing in Venezuela.

The situation in the Country

Hugo Chavez was elected president of Venezuela in 1999 (Hetland, 2016). He occupied the office for fourteen years, making the country espouse “a model of state-led redistributive development” (Hetland, 2016, p. 8). The model has substantially increased social spending, boosting Chavez’s power at home. However, while it was relatively successful in raising the standards of education and healthcare, it failed to produce any substantial growth in productive investment. The successor of Chavez, Nicolas Maduro, has also been unwilling to make meaningful economic reforms, thereby exacerbating Venezuela’s poor economic conditions. The output of the state-run oil giant PDVSA has decreased by 450,000 barrels a day, burning a hole in the country’s budget (Watts, 2016). Now the country is on the brink of a humanitarian catastrophe. A recent report issued by the Bengoa Foundation of Food and Nutrition suggests that the average weight loss in the country over the last five months is “between 5kg and 15kg” (as cited in Watts, 2016, par. 11). Malnutrition exacerbated by a shortage of drugs leads to “the re-emergence of long-dormant diseases such as diphtheria” (Watts, 2016, par. 11). Protests over food shortages is a commonplace occurrence in Venezuela.

The Resource Curse

According to Hammond (2011), academic interest in the theory of the resource curse was significantly fueled by the crash of oil prices on December 23, 2008. The resource curse is a term that was coined to describe the state of slow economic growth caused by the abundance of natural resources such as coal, oil, gas, and metals, among others (Deacon & Rode, 2012). It should be mentioned that Venezuela is only one of many countries that have fallen into the trap of overdependence on rich oil resources. Other examples include Angola, Congo, and Nigeria. Economists argue that the resource curse was responsible for the precipitous decline in Saudi Arabia’s per capita GDP growth between 1970 and 1999 (Deacon & Rode, 2012). Nigeria is a classic example of a country stricken by the resource curse. Even though the country had immense oil revenues in 2000, it’s per capita GDP was only 30 percent, which is significantly lower than in 1965 (Deacon & Rode, 2012). It should be mentioned that there are few countries whose experience does not support the hypothesis of the resource curse theory: Norway, Chile, Malaysia, and Botswana have managed to escape the downside of having an abundant supply of natural resources (Deacon & Rode, 2012). Therefore, it could be argued that there is no universal application of the theory; rather, unfavorable outcomes of the resource curse or lack thereof depending on “host country circumstances and on the particular resource involved” (Deacon & Rode, 2012, p. 2).

Rent-Seeking

In order to explain the phenomenon of the resource curse, economists have come up with the idea of rent-seeking. Even though rent-seeking behavior has been used to describe the establishment of monopolies and subsidies with the help of political institutions, it can also be used to explain the failure of political elites to transform wealth from natural resources into an overall benefit for their societies. According to Congleton et al., abundant natural resources become a curse “when property rights are not defined or respected, and the wealth turns into a rent-seeking prize” (as cited in Deacon & Rode, 2012, p. 2).

There is ample evidence suggesting that the resource curse might be brought about as a result of political elites engaging in rent-seeking. The increased domestic spending in Venezuela in the period between 1979 and 1981 mainly benefited government officials (Deacon & Rode, 2012). The growth of spending on infrastructure was so significant that the country “ran a current account deficit despite a large, favorable shift in its terms of trade” (Deacon & Rode, 2012, p. 3). Nigeria’s institutions were not as effective in discouraging rent-seeking as institutions of Norway, Chile, Botswana, and Malaysia, among others. Therefore, the share of oil revenues controlled by the elite amounted to 55% in 1970, increasing the fraction of people living beyond a poverty line by almost 45% (Deacon & Rode, 2012).

The economists interested in the phenomenon of the resource curse argue that the negative effects of having significant oil reserves could be controlled by political institutions of a country (Deacon & Rode, 2012). However, if there are no effective policies aimed at solidifying property rights, promoting democracy, and political stability, it is virtually impossible to avoid active rent-seeking. This idea was explored by Karl in 1997, who studied the economic record of six countries with rich natural resources (Deacon & Rode, 2012). She concluded that the locus of political authority rapidly changes with the discovery of mineral resources. According to the economist, the control over resource rents “becomes a basis for political power and institutions evolve to perpetuate existing patterns of control” (as cited in Deacon & Rode, 2012, p. 4). Karl’s analysis of Venezuela reveals that the country’s economy, which revolves around revenues from selling oil, has “promoted a rent-seeking culture and a patron-client system of governance” (as cited in Deacon & Rode, 2012, p. 4).

The fact that the Venezuelan government has complete control over oil-extracting companies has only exacerbated this trend. Robinson, Torvik, and Verdier (2014), in their article that explores political foundations of the resource curse, argue that governments without rigid institutions preventing rent-seeking always tend to form a patron-client relationship. However, patronage in a system “where all resource rents accrue to the government” could also take another, but no less virulent, form (Robinson et al., 2014, p. 196). The case of Venezuela demonstrates that it is possible to win numerous elections by providing people with gainful employment in the public sector (Levy, 2013). It should be noted that the share of the private sector economy decreased to a significant degree as a result of the aggressive policies of Hugo Chavez (Levy, 2013). Taking into consideration that the detrimental influence of rent-seeking creates numerous micro-foundations never benefiting populations of countries in which they are formed, it could be argued that oil in Venezuela was a curse and not a blessing.

Venezuela Before and After the Crash of Oil Prices

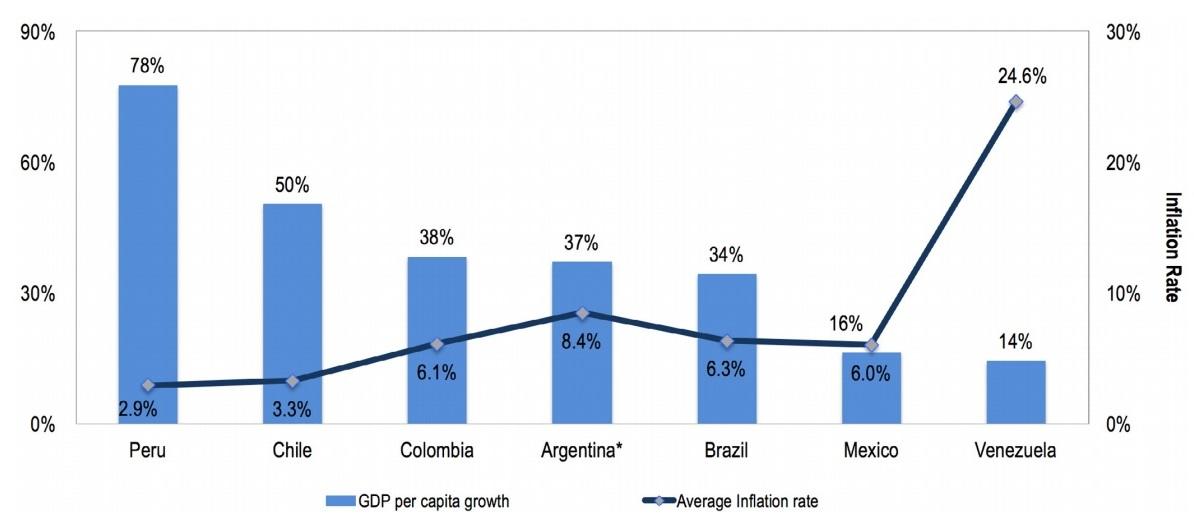

The crash of oil prices on December 23, 2008, was partially precipitated by the 2007-2008 economic crisis that drastically decreased global demand for oil (Hammond, 2011). Before the crisis, Venezuela had “the biggest international reserves per capita—a total US$34 billion reserves and US$ 1,300 per capita” (Lin, Leif, Chen, & Beding, 2014, p. 20). Rapid government spending was responsible for record rates of GDP growth: almost 10% in 2006, 8% in 2007, and about 5% in 2008 (Lin et al., 2014). Interestingly enough, the period between 2003 and 2009 was characterized by regional 120% growth of GDP on average, whereas the Venezuelan GDP was more than 300% (Columbia SIPA, 2015). However, a precipitous decrease in oil revenues caused by a drop in its prices in 2009 and 2010 led to the substantial inflation of the country’s currency—27% and 28%, respectively (Lin et al., 2014). The stagnation of the Venezuelan economy along with the increase in inflation rates to 68,5% in 2014 has deteriorated the situation even further. Figure 1 shows GDP per capita growth and inflation in the period from 1988 to 2013.

A recent IMF report reveals that the country’s economy will be in recession for at least three more years (Gillespie, 2016). Venezuelan currency, bolivar, is currently traded 1,262 to one dollar and is expected to fall even further as inflation rises to 475% (Gillespie, 2016). Because of the inability of the state-run oil company, PDVSA, to pay its contractors such as Schlumberger, oil production has fallen to a 13-year low level (Gillespie, 2016). As of October 2016, oil prices are near US$50 per barrel after hovering around US$27 at the beginning of the year (Gillespie, 2016). Taking into consideration the fact that oil revenues account for more than 95% of Venezuela’s budget and that PDVSA is risking default, it could be argued that Venezuela is on the brink of complete economic collapse (Gillespie, 2016).

Even though the country had one of the biggest foreign exchange reserves in the world, it was increased by only US$7 billion in the period between 1999 and 2014, whereas oil exports amounted to US$37 billion (Columbia SIPA, 2015). Therefore, it could be argued that Venezuela’s government demonstrated blatantly “imprudent macroeconomic behavior during the high price cycle relative to many other oil exporters” (Columbia SIPA, 2015, p. 6). It should be noted that there are economists who believe that the reduction of capital accumulation, rather than the resource curse, is responsible for the economic crisis in Venezuela (Kornblihtt 2015). According to Kornblihtt (2015), the sudden reduction in the accumulation of reserves resulted in “an expansion of the relative overpopulation, including not only the unemployed but also employees of private or state capital that operates with below-average productivity” (p. 71).

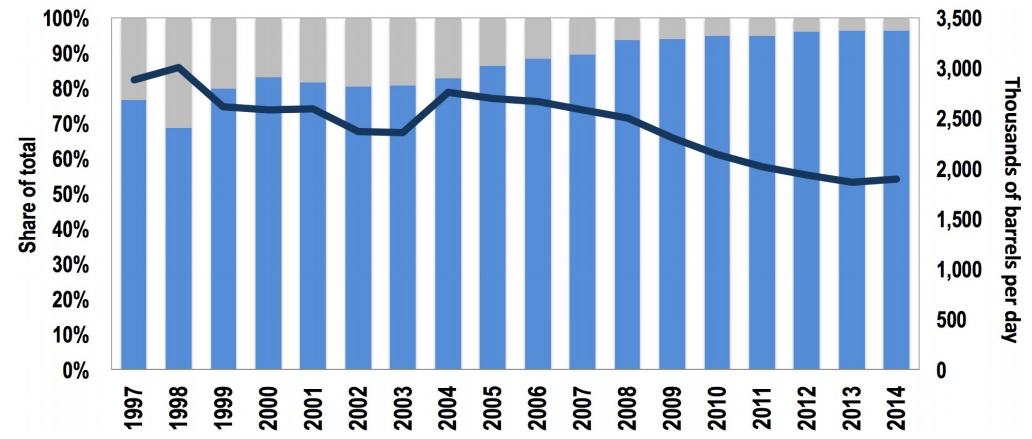

The period of the high oil prices was marked by the increase in economic dependency on the oil market. Since 2008, oil represented 96% of all exports, which constitutes a significant increase from 60% in the late 1990s (Columbia SIPA, 2015). However, the volume of oil exports fell by 30 percent since 1999 (Columbia SIPA, 2015). Therefore, Venezuela’s budget is dependent on the price of oil as never before. Figure 2 shows exports of the country in the period from 1997 to 2014.

The graph could also be used to illustrate the development of the Dutch disease, which is a term that is being used to describe a rapid decrease of the non-resource sector due to the growth of the resource sector (NRGI Reader, 2015). The process also occurs due to the exchange rate appreciation that could produce a long-lasting effect on a country’s economy. Unlike Chile, Indonesia, Norway, and Saudi Arabia, which were able to transform their resources into tangible investments into non-resource sectors and invest a share of their revenues in foreign economies, Venezuela did not have absorptive capacity able to prevent a decline in manufacturing (NRGI Reader, 2015). Therefore, it could be argued that Dutch disease is another reason why oil in Venezuela was a curse and not a blessing.

Democracy

There is ample evidence suggesting that reliance on natural resources is positively associated with the creation of authoritarian regimes (Haber & Menaldo, 2011). Data drawn over a long period reveals that the wealth from the extraction of minerals impedes “the development of democratic political institutions” (Ramsay, 2011). It should be mentioned that contributors to a large body of the existing literature on the link between the abundance of natural resources and democracy do not make a distinction between changes in revenue resulting in changes in a country’s internal politics and changes in revenues stemming from shifts in political structures (Ramsay, 2011). In the case of Venezuela, it is clear that the significant growth of oil revenues coincided with the consolidation of power by Hugo Chavez (Hetland, 2016). It cannot be said that his rule was an outright dictatorship: “Chavez’s party won sixteen of seventeen elections held between 1988 and 2012” (Hetland, 2016, p. 8).

Jimmy Carter even called the country’s electoral system “the best in the world” (Hetland, 2016, p. 8). However, after Chavez’s death in 2013, Venezuela was headed by Nicolas Maduro, who faced numerous violent protests. Despite the significant push from the country’s opposition, he refuses to step down from the office (Hetland, 2016). Moreover, some Venezuelan courts proclaimed that “the signatures gathered to activate a recall referendum” were annulled. It means that democracy in the country is currently in a suspended state (Prieto, 2016, par. 2). It should be noted that over 80 percent of Venezuelans wanted to remove their president (Prieto, 2016). It could be argued that anecdotal case of the country confirms that there is a positive connection between the creation of authoritarian regimes and the abundance of natural resources. Therefore, the deterioration of democracy could serve as another explanation of why oil in Venezuela was a curse and not a blessing.

Conclusion

The end of the last cycle of high oil prices it 2014 has revealed that oil wealth was responsible for the deterioration of the Venezuelan economy. As a result of immense revenues from the sale of oil, the country found itself trapped in the vicious cycle of ever-increasing public spending that had been traded for political clout of the ruling party and its head—Hugo Chavez. Rent-seeking, the Dutch disease, and the weakening of democratic institutions explain why oil resources are a curse instead of a blessing in Venezuela.

References

Columbia SIPA. (2015). The impact of the decline in oil prices on the economics, politics and oil industry of Venezuela. Web.

Deacon, R., & Rode, A. (2012).Rent seeking and the resource curse. Web.

Gillespie, P. (2016). Four reasons why Venezuela became world’s worst economy.CNN Money. Web.

Haber, S., & Menaldo, V. (2011). Do natural resources fuel authoritarianism? A reappraisal of the resource curse. American Political Science Review, 105(1), 1-26.

Hammond, J. (2011). The resource curse and oil revenues in Angola and Venezuela. Science & Society, 75(1), 348-378.

Hetland, G. (2016). Chavismo in crisis. NACLA Report on the Americas, 48(1), 8-11.

Kornblihtt, J. (2015). Oil rent appropriation, capital accumulation, and social expenditure in Venezuela during Chavism. World Review of Political Economy, 6(1), 58-73.

Levy, D. (2013). Squeezing the nonprofit sector. International Higher Education, 71(1), 10-12.

Lin, C., Leif, E., Chen, J., & Beding, T. (2014). National intellectual capital and the financial crisis in Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Mexico, and Venezuela (1st ed.). New York, NY: Springer.

NRGI Reader. (2015).The resource course: the political and economic challenges of natural resource wealth. Web.

Prieto, H. (2016). Venezuelan Democracy in Limbo.The New York Times. Web.

Ramsay, K. (2011). Revisiting the resource course: natural disasters, the price of oil, and democracy. International Organization, 65(1), 507-529.

Robinson, J., Torvik, R., & Verdier, T. (2014). Political foundations of the resource curse: a simplification and a comment. Journal of Development Economics,106(1), 194-198.

Watts, J. (2016). Venezuela on the brink: a journey through a country in crisis.The Guardian. Web.