Oligopoly is a type of market structure that has few companies but with huge capital bases. ‘Few firms’ in this case are taken to mean that the activities of one firm are largely influenced by the activities of the rest of the firms in the industry. In other words, interdependence is eminent. Should one firm, for instance, decide to change the price or make any other fundamental decision, others will follow suit.

Such examples would include the print media such as the Newspaper Industry. All companies would decide to charge same prices not because of their individual choices but because of the demands of the market.

Readership (sales) in this case will depend on factors other than the price, such as the efficiency of distribution channels (accessibility), quality of the content, subscription and publicity. These factors are popular referred to as non- price aspects of competition.

Cost & Revenue

Equilibrium in Oligopoly

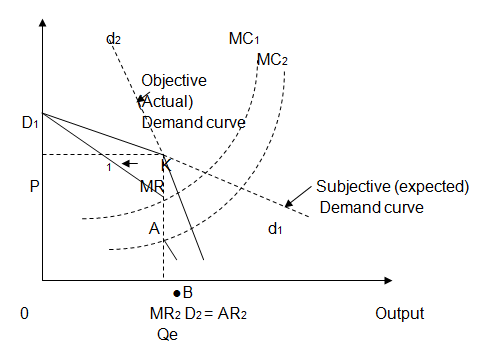

Any rational firm in an oligopolistic market cannot increase the price above P because it knows very well (perfect knowledge) that it would be pricing itself out of the market, since other firms in the industry will most probably keep their prices stable at P and therefore having a high relative demand.

The objective demand is represented by d2. K is not attainable since an increase in price by an individual firm above P will lead to a fall in the quantity demanded, taken from the demand curve D1 K. Again, the price cannot be reduced below P since each firm knows well in advance that any such move would be followed by the rest of the firms in the industry with a view to maintaining their market shares.

Thus, the subjective demand Kd1 cannot be individually taken as an advantage because of the tendency for simultaneous pricing decisions. Therefore, there is a high tendency for prices to remain rigid at P, with the relevant market demand curve being D1 D2 with a kink at point K. The high degree of substitutability of oligopoly products makes the demand for products to be highly price elastic.

Oligopoly in the market describes a situation in which firms are price makers. Product differentiation and supernormal profits are earned both in the short run and long run. Because sellers are few, the decisions of sellers are mutually inter-dependent and they cannot ignore each other because the actions of one will affect others (Kreps, 1990).

Pricing and Output Decisions of the Firm

The price and the output shall depend on whether the firm operates in either pure oligopoly or differentiated oligopoly. Oligopoly market normally differentiates its products. But this differentiation might either be weak or strong. Pure oligopoly describes the situation where differentiation of the product is weak. Pricing and output in pure oligopoly can be collusive or non-collusive.

Collusive oligopoly refers to a situation where there is co-operation among the sellers that is, co-ordination of prices. Collusion can be Formal or Informal. Formal collusive oligopoly refers to a situation where firms come together to protect their interests for instance, cartels such as OPEC. In this case, members enter into a formal agreement by which the market is shared among them.

The single decision maker will set the market price and the quantity offered for sale in the industry. There is a central agency which sets the price. The maximized joint profits are distributed among firms based on an agreed formula.

Informal collusive oligopoly can arise mainly because of two reasons. One of them is when the cartel may be weak or unable because of legal requirements or some may be some firms do not want to enter into an agreement or lose their freedom of action completely. Firms may find it mutually beneficial for them not to engage in price competition.

When a cartel does not exist then firms will collude by covert gentlemanly agreement or by spontaneous co-ordination designed to avoid the effects of price war. One such means by which firms can agree is by price leadership. One firm sets the price and others follow with or without understanding (Vives, 1999). When this policy is adopted, firms enter into a tacit market-sharing agreement.

Price Leadership

There are two types of price leadership. One of them is referred to as the by a low-cost firm pricing model. When there is a conflict of interests among Oligopolists arising from cost differentials, the firms can explicitly or implicitly agree on how to share the market in which the low-cost firm sets the price. We can assume that the low cost firm takes the biggest share of the market.

Another price leadership model is referred to as the price leadership by a large firm. Some Oligopoly markets consist of one large firm and a number of smaller ones. In this case, the larger firm sets the price and allows the smaller firms to sell at that price and then supplies the rest of the quantity.

Each smaller firm behaves as if in a purely competitive market where price is given and each firm sells without affecting the price because each will sell. The formula can be given as follows.

MC = P = MR = AR

Non-collusive oligopoly on the other hand operates in the absence of collusion and in a situation of great uncertainty. In this case, if one firm raises prices, it is likely to lose a substantial proportion of customers to its rivals. They will not raise the prices because they have the interests of charging a price that is lower than that of their rivals. If the firm lowers the price, it would attract a large proportion of customers.

The other firms are likely to retaliate by lowering their prices, either to the same extent or a large extent. The first firm will retaliate by lowering the price even further. As firms would always expect a counter-strategy from rivals, each firm prices and makes decisions that are tactical. This would then lead to a price war.

If it goes on, there would come a time when the prices are so low that if one firm lowers the price, the consumers will see no point in changing from their traditional suppliers. Thus, the demand for the product of the individual firm would start by being elastic and it would end by being inelastic.

The demand curve for the product of the individual firm thus consists of two parts, the elastic part and the inelastic part. It is said to be “kinked’ demand curve, as shown below (Samuelson, & Marks 2003).

If the firm is on the inelastic part and it raises the price, others will not follow suit. But on this part, prices are so low that it is likely to retain most of its customers. If it raises the prices beyond the kink, it would lose most of its customers to rivals. Hence, the price p will lose most of its customers to rivals.

Hence the price p will be the stable price because above it, prices would be unstable. Rising prices means substantial loss of customers and lowering prices may lead to price war. Below p, prices would be considered too low.

References

Kreps, D. (1990). A Course in Microeconomic Theory. Princeton: Princeton Press.

Samuelson, W., & Marks, S. (2003). Managerial Economics page (4th ed). New York: Wiley.

Vives, X. (1999). Oligopoly pricing. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.