The cyberspace has witnessed a criminal insurrection in the past few years. Nowadays, cybercriminals use elementary concepts to conduct deceptive online transactions.

What’s more, organizations face an extremely complicated task of developing a safe network system. One of the most notable dissimilarities from conventional engineering speciality is the prevalence of creative and expert hackers who attack such systems. There are numerous factors that enhance the vulnerability of a secured network system. For example, the escalating computer and software connectivity is one such factor.

The pressure to distribute systems via internet presents additional threats since cyber criminals can instigate online attacks easily. In addition, although the prevalence of program extensibility provides flexible software for novel business requirements, it also creates avenues for superfluous malevolent extensions (Netland, 2008, p. 3).

Risk Analysis and Mitigation

Vulnerability refers to a system bug or a design error whereas a threat refers to a skilled antagonist who aspires to take advantage of vulnerability within a network system (Netland, 2008, p. 16). The following sections discuss various threats and vulnerabilities prevalent within network systems.

Man-in-the-Middle Attack

This is a form of communication attack where the hacker relays bogus messages to the operator. Usually, the hacker sends messages to the system operator signifying a system change. When the system operator tries to rectify the problem by following the laid-out procedures, the hacker seizes this opportunity and attacks the system.

The man-in-the-middle attack is also known as integrity attack since the actions of the system operators are based on the integrity of the data. However, man-in-the-middle attack is a complex cybercrime since the attacker must possess exceptional skills and collect a lot of information passing through the network to be able to launch an attack (Yu-Lun et al, 2009, p. 69).

Terminal-to-Terminal Attacks

When students access university websites via mobile terminals, hackers can launch their attacks using a direct wireless connection through a wireless access point. In addition, hackers can use the wired infrastructure to launch attacks on an open wireless network. For instance, hackers can install a rogue access point that operates malevolent software.

Therefore, mobile terminals are extremely susceptible to this attack if they lack updated antivirus software as well as firewalls. It is worthy to note that malicious access points can result in grave security breaches since they bestow hackers with authenticated access to information assets of the university (Netland, 2008, p. 16). Thus, it is important that malicious access points are identified and eliminated.

Threats on Local Networks

Cybercriminals usually employ spoofing attacks to gain access to information on the wired infrastructure. This happens when the network perimeter authentication is removed from the local network systems. In many cases, an attacker unlawfully poses as another person to access confidential data on the network. For example, when nonessential data are accessible without authentication, hackers are able to launch bogus services (i.e. fake research papers or phony lecture notes).

Nonetheless, this vulnerability can be alleviated by mounting firewalls and antivirus software on the university servers. In addition, the IT staff should run auditing programs to monitor activities of online users. Audit logs should also be reassessed on a regular basis in order to identify unlawful activities as well as detect attackers (Netland, 2008, p. 17).

In addition, universities require strong authentication to ensure that confidential data is only accessed by authorized users. Password-based authentication require end-to-end encryption between the server and mobile end-users since hackers can easily sniff usernames and passwords on encrypted wireless connections. What’s more, students must be compelled to access sensitive information via SSL, Secure Shell (SSH) or encrypted virtual private networks to alleviate spoof-attack threats.

It deserves merit to mention that procedures for alleviating threats on non-sensitive information also mitigate those associated with sensitive data. As such, confidential data (i.e. medical information) should not be uploaded on any online-linked network (Netland, 2008, p. 17). In conclusion, university networks must have a strong design that utilizes robust encryption as well as robust authentication in order to safeguard confidential data.

Security Measures

Service-Level Authentication

Given that end-users are required to authenticate themselves prior to accessing confidential data on the network; the IT staff must modify the strength of the authentication in order to accommodate security requirements of a particular service. A strong authentication (i.e. public-key infrastructure or hardware token) should be used to access confidential data while access to non-sensitive information can be done using password-based authentication.

In addition, the network perimeter must have security mechanisms (i.e. intrusion detection systems and firewalls) whereas the internal defense system should incorporate security systems (on the server and user) where the data is stored. In addition, monitoring systems must be deployed by the IT staff to make sure that all users conform to the prescribed security protocols (Hole et al., 2008, p. 15).

Network Boundary Authentication

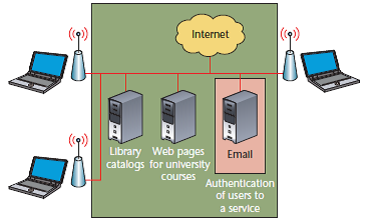

Figure 1 illustrates an information system model whereby wireless access points communicate with remote terminals to access servers. Users are authenticated by the system (at the network perimeter) before they can access any information. The authentication boundary is indicated by the black line.

Information contained within the boundary can only be accessed by users with valid authentication. The red line shows data flow between the end-users and the server. Since the network boundary authentication is only relevant to wireless end-users, access to confidential information is limited to those users with an extra service-level authentication (Hole et al., 2008, p. 15).

Security Policies that Address Threats and Vulnerabilities

The public sector and the private sector are currently engaged in a series of policy discussions to develop strategies to protect control systems from cyber attacks. For instance, a number of documents have been developed by the American Gas Association. These documents propose best practices to safeguard network systems communications from cyber attacks.

The proposed practices lend credence on the privacy of network system communications. In addition, the American Petroleum Institute (API) has developed some guidelines to improve control system security and integrity in the oil and gas sector (Yu-Lun et al, 2009, p. 70).

The public sector has also developed a number of security policies to mitigate cyber crimes. For instance, the Department of Energy has developed a 10-year security plan for mitigating cyber attacks in the energy sector. The plan focuses on four key areas:

- Evaluating the present security status;

- Crafting and assimilating defensive measures;

- Identifying intrusion and adopting response plans;

- Preserving security enhancements.

Many organizations are currently using wireless sensor networks in their systems to transmit and receive crucial information. Consequently, several organizations have collaborated to introduce sensor networks their process control systems as well as synchronize their communications.

Their wireless communication suggestions allow an organization to configure integrity mechanisms with end-to-end and hop-by-hop mechanisms. In addition, the proposal offers vital protocols for key management and access control (Yu-Lun et al, 2009, p. 73; Netland, 2008, p. 39).).

Risk Assessment Strategy

Man-in-the-Middle attack is undoubtedly the most severe form of cyber attack. The following sections discuss phases of risk assessment strategy for Man-in-the-Middle attack (Netland, 2008, p. 38).

System Description

This phase entails identifying system assets and information such as system users, network topology, software, and hardware (Netland, 2008, p. 38).

Threat Identification

The purpose of this phase is to identify individuals (or groups) who may deliberately take advantage of vulnerability within the system to an attack. These entities consist of insiders, script kiddies and organized crime (Netland, 2008, p. 39).

Vulnerability Identification

This phase entails identifying all potential flaws within the system that could permit attackers to compromise the system’s security (Netland, 2008, p. 38).

Risk Assessment

A risk level is allocated to each threat/vulnerability pair on the basis of the probability of happening and the resultant impact (Netland, 2008, p. 39).

Risk Treatment

This phase deals with finding the best strategy to mitigate the potential threat/vulnerability pair identified. Usually, a risk acceptance threshold indicates the risk level that can be tolerated by the organization. If the identified threat/vulnerability pair transcends this threshold, it can be mitigated in three ways:

- Adopting corrective strategies to diminish the risk to acceptable level;

- Employing workarounds to evade the threat;

- Relocating the threat to other parties, such as insurance providers (Netland, 2008, p. 39).

References

Hole, J., Netland, L., Helleseth, H., & Jan, B. (2008). Open Wireless Networks on University Campuses. IEE Security & Privacy, 14-20.

Netland, L. (2008). Assessing and Mitigating Risks in Computer Systems. Norway: University of Bergen.

Yu-Lun, Huang., Alvaro, Cárdenas., Saurabh, A., & Shankar, S. (2009). Understanding the Physical and Economic Consequences of Attacks against Control Systems. International Journal of Critical Infrastructure Protection, 2(2), 69-134.