Introduction

The central focus of the present research project was to determine the effectiveness of the possibility of using color coding as a tool for better learning grammatical constructions of English as a foreign language. The sample formed was composed entirely of female students from the English Language Institute with the same level of initial knowledge of the discipline, namely pre-intermediate. Thus, all of the participants in this test were not native speakers of English but would be native speakers of Arabic — more specifically, the Saudi Arabian or Hejazi dialect — learning a foreign language as ELLs. Manipulating color schemes when tutoring students in the experimental and control groups through the use of color or black and white articulation and quantifiers was an intervention to assess the effects of color coding on short-term and long-term, up to one month, English articulation and distractor skills. This chapter details the findings from the entire study, examining them in terms of effectiveness, applicability, and relevance to the current agenda. In addition, this section uses data from authoritative literature sources in order to frame the evidence obtained theoretically. The overall structure of the Discussion section can be roughly divided into two paragraphs. The first interprets the results in terms of prior research and existing theory, that is, placing the findings within the framework of academic justification. The second part critically evaluates the potential implications and perspectives of the findings and, in addition, identifies some possible ways in which they might be used in an educational setting for ELL students.

Discussion of Test Results or Quantitative Approach

The pre/post longitudinal testing conducted revealed a critical result. Color coding was shown to be effective in increasing students’ average test scores on English articulators and distractors. Discussing these data differently, it can be stated that sufficient evidence was found that color coding of instructional materials actually made it easier to perceive and remember information, which had an effect on improving academic performance. Similar results were found in a 2019 study for which the use of color coding was shown to increase average test scores by nineteen units (Nurdiansyah et al., 2019). In the present experiment, the increase in mean score for the experimental group was not as significant at 6.35. However, it seems that the difference in the quality of the score increase is not such a relevant topic for discussion, as it raises many more factors related to test typology and structure, conditions, and sampling; instead, it is essential to emphasize that color coding is indeed a proven tool for increasing student performance.

In examining the outcomes of the present test, it was crucial to determine precisely what was included in the concept of “student outcomes” used in the previous paragraph. On the one hand, there is a particular bias in linking these outcomes to increased student achievement in English language learning. Extrapolating this reasoning could lead to the untested and possibly potentially erroneous claim that color coding improves foreign language learning. On the other hand, since tests have been used as tools to test students’ knowledge, one might hypothesize that color coding has been helpful for short-term memorization. In particular, this hypothesis can be indirectly confirmed by the results obtained: one month after the post-test results, respondents in both groups showed a drop in their scores. Finally, the preparation lessons were structured around a presentation using handouts, which means that it can be assumed that the experimental intervention increased receptivity to new information. Thus, the increase in mean scores during the training could have been justified either by an increase in the students’ performance, by stimulating their memory, or by an improvement in their perceptual skills.

Notably, it is the effects on learning information recall that are among the most frequently cited in the academic literature. In a seminal paper on color coding, Pruisner (1993) stated that a student’s academic productivity is enhanced through improved information recall in the presence of a color cue. Theoretically, the results are entirely consistent with Pruisner’s findings: students in the experimental group did show an increase in academic performance as assessed through a short test. Regarding memorization, it is impossible not to discuss the observed long-term effect of color coding. According to the results, the effectiveness of the pedagogical tool was maintained after one month: in contrast to the control group, the drop in average test scores was only 4.7 percent compared to an almost two-fold decrease for the group of students without the intervention. Simultaneously with this change, there was a change in the standard deviation. For the experimental group, the standard deviation as a measure of the spread of data around the mean increased by only 0.191, whereas for the control group not using color coding in instruction, the SD increased by 0.730. In other words, this pedagogical tool appeared to be responsible for the fact that even after one month of instruction, most students retained knowledge of correct article and distractor spacing. In contrast, students in the group without color coding were about six times as likely to give incorrect answers. This led to a legitimate conclusion: color coding maintained its effect after one month and thus probably could have had longer-lasting positive effects as well. A long-standing study proved the effect of color coding on the retention of critical information in memory: “information will be stored in the long-term memory store…” (Dzulkifli & Mustafar, 2013). It becomes possible to assume, if one takes into account the longitudinal graph of changes in average scores, that the main effect of color coding consists both in a sharp short-term increase in academic performance and in long-term storage of information, that is, its assimilation. Thus, the results obtained are in good agreement with the academic evidence.

To a certain extent, it can be stated that the color-coding system has a connection with the respondents’ behavior if this behavior is expressed in language acquisition skills. This has not been tested or confirmed in the current study, so it can only be formulated a hypothesis based on the results, which is that color coding caused students to be more attentive and engaged in the educational process. The outcome of this behavior might have been a change in the results of the test being analyzed. From this point of view, the article by W. Alhalabi & M. Alhalabi (2017) which describes that color coding allowed school administrators to manage student behavior, which had a positive effect on student learning outcomes. If one applies these findings to the present experiment, one can conclude that the improvement in students’ average scores may indeed have been mediated by changes in their learning behaviors. In particular, this assumption could be an explanation for the effect of increasing mean scores for the two groups observed at once. Beginning with roughly equal conditions, the experimental group increased its mean score by 157 percent, while the control group was also able to produce a score increase of 139 percent. Consequently, for the first group, color coding may have caused a change in academic behavior management, which had an effect on the increase in mean test scores, but this still remains a hypothesis that requires further testing.

A feature of the present test was the fact that, unlike the instructional materials, the test items were not color-coded. In other words, students who were used to color-coding information during instruction were able to show reliable results even in the absence of color coding in the test materials. Interestingly, the findings contradict the results of a recent study, according to which the academic effect of such a pedagogical tool only makes sense when the test materials are also color-coded (Skulmowski, 2021). The conducted study showed that color highlighting demonstrates high effectiveness also in the case of using the same color schemes for the control and experimental group, which means that test materials do not necessarily have to have color. At the same time, the obtained contradiction confirms the unsustainability of the popular pedagogical opinion, including that confirmed by the experiment, conducted that color coding is academically beneficial. In other words, there is a particular knowledge gap that does not allow for a guaranteed statement of test conclusions.

Discussion of Interview Results or Qualitative Approach

The second outcome of this research project was the results of a thematic semi-structured interview in which six participants in the experimental group were interviewed about their impressions and opinions of the color-coding experience. One of the central findings of this part was to determine a trend in the better perception of color content compared to black and white content. In fact, the results of the qualitative analysis could not lead to unequivocal conclusions, as each of the subjects had their own opinions: this created a pool of the most common and uncommon themes that required additional discussion.

As noted in the Results section, Participant #1 associated color coding with easier processes for remembering information. This subjective view of the respondent is entirely consistent with the data that was validated for the quantitative approach. In other words, a correlation was indeed found between textual information memorization and color coding. Among other trends that were mentioned by the respondents, the ability to concentrate and focus on the material being studied better stands out. This is entirely consistent with evidence from other work: color elements do allow for the retention of a student’s attention on specific objects (Hannon, M. A., & Raymond, 2018). However, the use of color to highlight specific parts of the learning material and its relationship to focus does not seem necessary for further explanation due to its obviousness.

At the same time, a parallel should be drawn between the features of such highlighting and outcomes. One respondent answered that the use of a single color, be it black, red, or green, makes no sense with respect to color coding because there is no highlighting. To put it another way, it is not so much the color that plays a role in color coding, but rather its contrast in comparison to the text of the rest of the font. From this, one can conclude that the use of excessive highlighting, for example, to write each word in different shades, is of no educational benefit, but on the contrary, creates a feeling of not being serious for the perception of the material. In turn, the idea being developed begs the legitimate question of whether the color of textual emphasis makes sense.

The psychology of color is a severe branch of educational and organizational psychology because the clever use of hues and their combinations seems likely to produce the desired result (Qayumovich, 2021). Several color cues were used in this study: orange, green, and blue, in addition to the default black. The authors tend to interpret the meaning of the colors differently, but some common patterns for most of the work are noticeable. For example, green and blue tend to be used for rest and calming but may additionally be aimed at increasing an individual’s concentration and efficiency, while warm hues (orange, red) can hold a student’s attention during learning (Chang & Xu, 2019). Once again, however, a real problem is created that, if not addressed, can be detrimental in the case of color coding: it concerns the presence of students with colorblind disorders in the classroom, which result in qualitatively altered perceptions of color (Zorn & McMurtrie, 2019). If the teacher is not aware of such issues, then using specific colors to achieve desired outcomes has the potential to become a problem for individuals with color vision impairments conversely. Combining the evidence from the academic literature with the interview results of the current experiment allows us to confirm that the use of the correct colors does make a difference in the educational benefit of the classroom.

An additional and not uncommonly mentioned effect of color coding was the ability to ensure consistency of the material. Indeed, when a presentation is presented only in black ink — in the absence of other visual elements — the commonality of connection between slides can be compromised. On the contrary, when an essential material to capture is highlighted in a particular color on the slides, it makes sense, according to the results, to create narrative logic and consistency. Using this approach can play a meaningful role for lengthy presentations, in which a large number of slides can be a negative factor for attention retention. Consistency is also essential in terms of assigning specific colors to the same elements of instructional material. For example, if at the beginning of a large presentation, orange was used to highlight the correct answers and green was for guiding comments, then using the same colors throughout the presentation for the same designations seems like a logical and appropriate strategy instead of mixing them up, which can confuse the student.

An interesting parallel has been drawn between color-coding text and highlighting individual words using the editor’s built-in tools, whether bold or italic. It is common knowledge that either form of text highlighting has the sole purpose of creating more appealing content that enhances the perception of textual information. However, the effect of text highlighting itself seems to have no scientific validity in the academic environment. For example, there is ample evidence that textual highlighting proves ineffective for literal questions whose answer must be within the text being studied (Ben-Yehudah & Eshet-Alkalai, 2018). Similar results were reported in a controversial meta-analysis by Cui (2018), who found that “highlighting text is not an effective or reliable way to study for a test” (para. 5). Although the results of the present experiment suggest otherwise, it is fair to point out then that studying the pedagogical effects of highlighting text is still a task for the educational sciences.

For the color cues that were used in the present study and for which performance was found to be superior to the control group, one can parallel the theory of Input Enhancement (IE). IE was proposed by Mike Smith at the end of the last century as an effective tool for teaching a second language to draw students’ attention to specific lexical constructions of speech (Bakhshandeh & Jafari, 2018). In this sense, color coding, which has been used to highlight articles and distractors, is a private practice of EI theory. Hence, color coding can allow specific constructions of speech to be understood even without respondents’ understanding of English. The use of orange to highlight articles allowed for a sequence in which all correct articles could be highlighted in orange – so even without understanding the more complex uses of such articles, students could know precisely what they meant and why “an” was replaced by “a.” This is entirely consistent with the theory of Input Enhancement, which means that it can be said to have proven academic effectiveness.

The final focus of the semi-structured interview was to determine students’ personal experiences with test-taking. Enjoyment of the activity is a central predictor of engagement because, in an educational setting, students without interest in the lesson do not perform well (Putwain et al., 2018). Of particular relevance to the discussion of these findings is Paul Ekman’s theory of the six emotions, who identified the primary states common to all humanity: they are joy, anger, disgust, surprise, fear, and sadness. In fact, each of these emotions has the effect of engaging in activities, including education (Hernik & Jaworska, 2018). In terms of the results found, the pleasure of taking the test (“fun,” “creativity”) can be attributed to the emotion of joy. Then, most students’ experience of taking the test may be associated with increased engagement in the research process. These findings are in good agreement with the theories of positive psychology for learning ELLs (Liu et al., 2021). Consequently, this enthusiasm from teachers has a beneficial effect on ELL/ESL students.

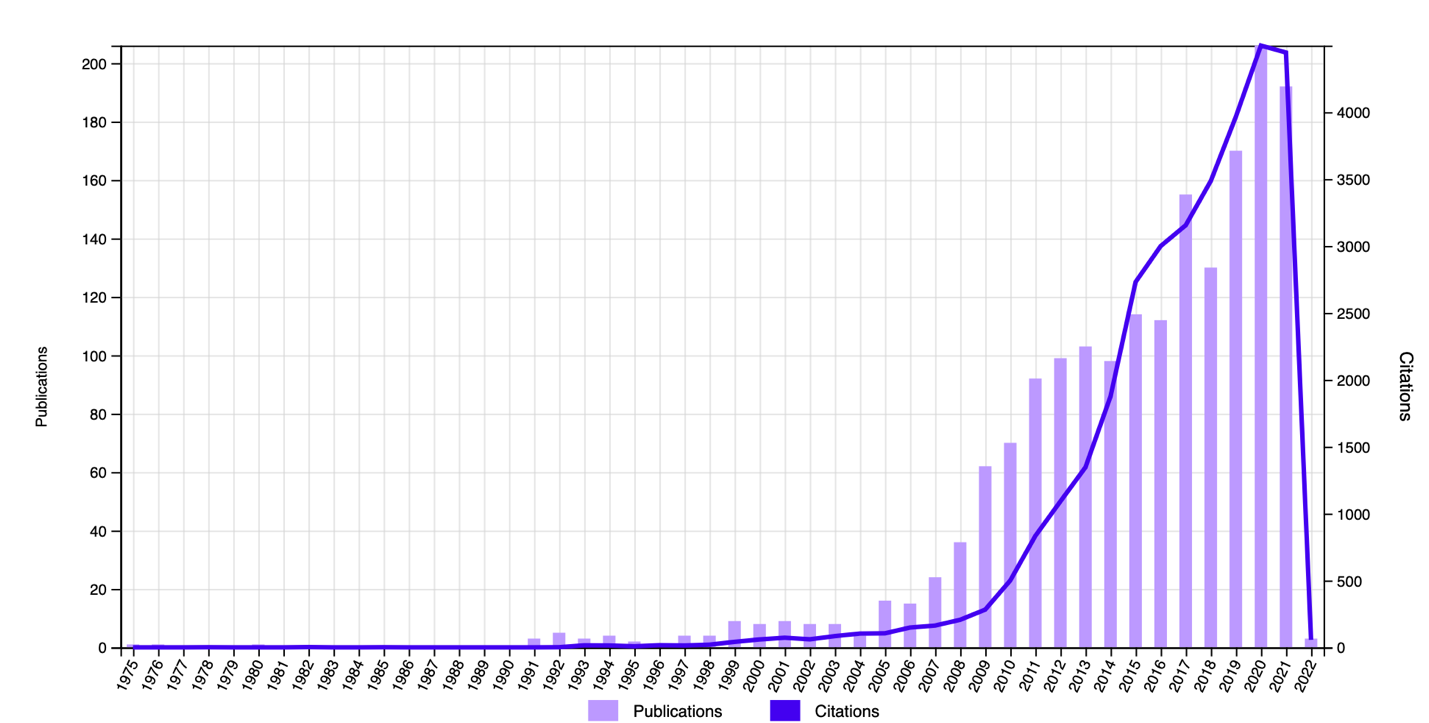

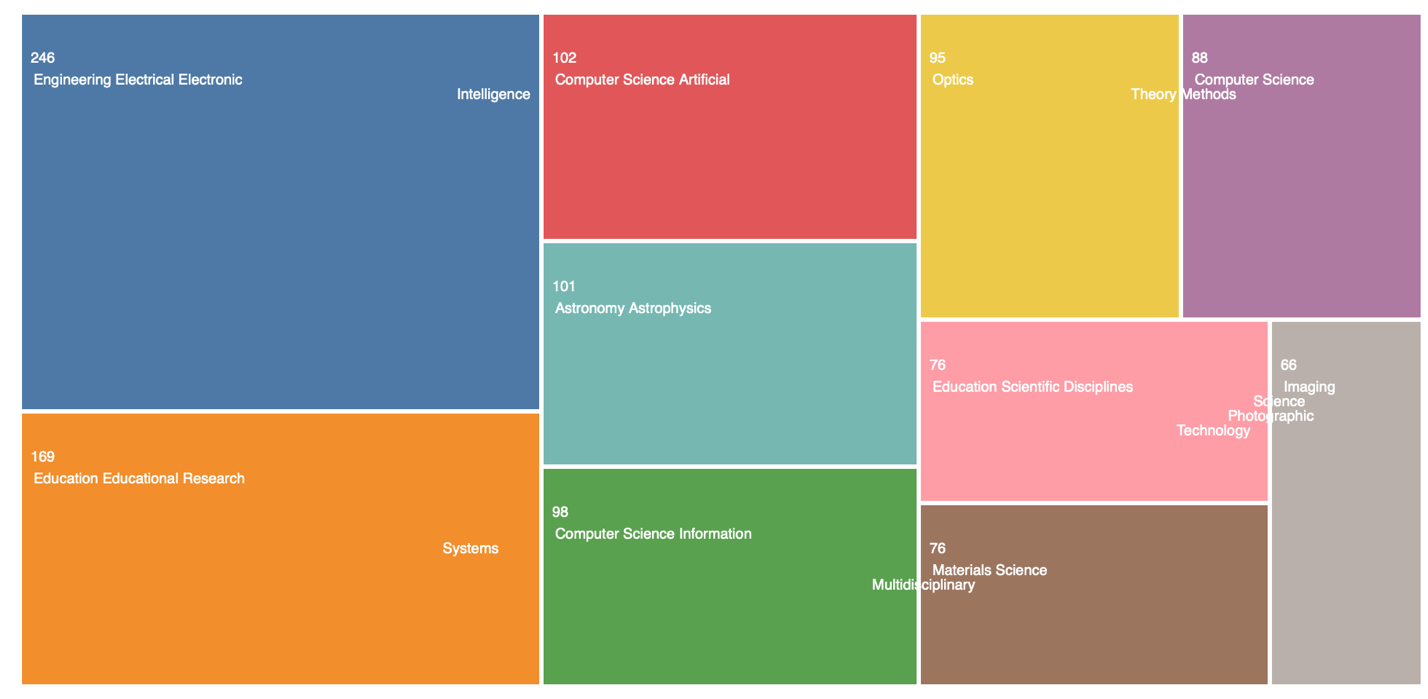

In addition, students noticed that color-coded instruction was a new experience for them. The academic environment is dynamic and ever-changing, and for this reason, learning new pedagogical practices is an essential component of keeping the educational process relevant. If an educator does not have the time and desire to explore new approaches to instructing young people, it can cause a decrease in engagement on the part of students who do not see the teacher’s interest. As it was noted, the lecture held included theoretical and practical types of learning, as well as fully used digital tools to convey educational information. The use of technology in teaching is one of the approaches of innovative education that students tend to like (Li et al., 2018). It is not known, however, precisely what respondents found “new” about their proposed participation in the experiment. The use of color coding to highlight fragments is not an entirely innovative practice, as is clearly evident when one turns to Figure 1. The academic community has been studying the use of color coding in educational settings for thirty years, and it is not only related to learning English as a foreign language. In particular, Figure 2 illustrates well the main areas of scientific knowledge within which works devoted to the use of color coding in education have been published.

From the data revealed, it can be concluded that color coding is not an entirely new practice for the educational sciences, but nevertheless, the majority of respondents identified it as new to them. Possible reasons for this phenomenon are either the lack of use of color coding by ELI teachers in which participants learn or the lack of attention to students’ use of the tool. Either way, the respondents are now familiar with this practice, which means they will be able to notice it if it is used in the educational process or even use it themselves in the case of group or individual presentations. On the other hand, it is possible that the particular pedagogical approach used by the teacher in designing the lesson was described as “new” in relation to the lecture. Thus, it cannot be determined conclusively what was new/innovative for the respondents, but the beneficial effect of this novelty cannot be ruled out. Even for the two participants who expressed confusion about the use of new pedagogical tactics, it was shown that their opinions changed over time.

Another component that measures the consistency of the findings with the theoretical data is the use of color coding to enhance student cognitive abilities. In Lacy’s (2020) independent thesis and Eckert & Nilsson’s (2019) article, color coding was found to make sense in learning mathematics because it allowed for the expansion of literal learning through the creation of deeper understanding. For example, Eckert & Nilsson (2019) showed how color-coding arithmetic procedures helped elementary school students perform calculations even without a complete understanding of numbers and counting procedures. These data show that color coding can create a memory organization in which the student predicts further solution pathways if they have some background previously. Extrapolating this finding to the current study suggests that similar findings were reported by interviewees. More specifically, one respondent stated that the presentation was consistent, implying that it was intuitively clear what knowledge would be offered on the next slide based on the experience of reading the previous one. Moreover, with respect to the post-test, it is very likely that the color coding exciting memories of color-coded articles in the minds of students in the experimental group, and thus reminded them of the rules of their use, which probably had an effect on the better performance of such students.

Implications for Pedagogical Practice

The discovery of the results of the present study has potentially long-lasting implications for educational practice. By now, it is crucial to recognize that the educational system is a dynamic and multifactorial environment that tends not to be sustainable. Education is constantly changing, and even the practices of twenty years ago may not be relevant to today’s college and university agendas. One of the most apparent advances has been the widespread use of technological solutions that qualitatively simplify administrative work in the classroom (Li et al., 2018). Technology is helping to automate many learning processes, reduce resource costs, and create engaging learning. In addition, an unobvious consequence of using digital technology in the classroom is the stimulation of environmental stewardship as a result of reducing the use of paper-based media. When using technology, the color-coded text tool has become particularly relevant because highlighting specific words, fragments, or answers on slides is a straightforward and quick task. It has already been shown in previous sections that color coding is generally consistent with most of the academic literature and has a proven effect on student learning, particularly ELLs/ESLs. Color coding was used intelligently and in sufficient quantity in the present experiment, and thus it can be said that a balance between color coding and retention of the reader’s attention was achieved. The present section discusses the pedagogical implications that result from the use of this tool in the classroom.

One of the first and most obvious consequences is the simplification of information perception among students. Proper color-coding of materials, taking into account the psychological meaning of colors and avoiding overemphasis, has already been shown to help increase student engagement and performance. It also activates their long-term memory, which has been proven through delayed testing. As a consequence, the use of color coding in the classroom gives the teacher powerful potential to qualitatively improve student outcomes in both the short and long term. It creates apparent organizational simplicity, clarity of narrative, and a focus on critical parts of instruction. However, it should be clarified that the present study did not test the systematic use of color coding. Specifically, the experimental intervention involved providing four hours of English grammar instruction to ELL students: it was the intervention that had the expected effect of increasing achievement immediately and after one month. However, it was not tested what results regular use of color coding in each lesson would lead to. The likely outcomes of such systematicity could be either a synergistic effect of maximizing academic achievement or, conversely, a decline to its former level. In the second case, one considers a situation in which the constant use of color in instructional materials ceases to be perceived as something surprising and demanding. In other words, students adapt to color coding, which means that it reduces effectiveness. Notably, the academic literature has not yet investigated the problem of student habituation to such an information-focusing tool.

Color coding offers the teacher many options for its use in the classroom environment. One of them is feedback, in which students who have previously learned articles and distractors use the same colors to emphasize them in the suggested text fragment. This tactic seems to be effective in terms of independent use of accumulated knowledge and, in addition, allows for a deeper reinforcement of the connection of color with specific designations in English grammar. In addition, color coding has been shown to help ensure consistency and logic in the narrative. Thus, using this tool can help ELL students organize knowledge. An example of this technique would be assigning specific books, stories, or handouts a specific color depending on the complex grammar used. Color coding, in this case, can give students the motivation to develop their skills to produce more complex work associated with color.

Additional use of color coding in the classroom is to avoid focusing only on articles and distractors but to expand the range of uses of color to learn English grammar and vocabulary. It is true that students need to learn new words, new vocabulary constructions, and sentence parts — be it predicate, subject, verb, or noun — in the study of English. Classifying these words makes sense for deeper learning of English as a second language, and using color highlighting for this purpose fully meets the academic goals of the class. The need for a creative component to the lesson can also be addressed through color coding by asking students to choose their own colors to be used for the lesson. This approach would support the humanistic paradigm of education and thus seeks to address the broad interests and needs of the audience (Chen & Schmidtke, 2017). Consequently, it is appropriate to conclude that the classroom will ultimately benefit from the use of color coding.

In addition, as the previous section suggests, the use of colors is associated with specific emotions and psychomental states of the individual. With this in mind, teachers can use specific colors to indoctrinate the class with specific emotions and manage moods in the classroom. For example, if the topic of study is historical material about wars and conflicts between countries, using “joyful” and “friendly” colors may not seem appropriate; however, using “aggressive” and “suggestive” shades of the color palette can positively reinforce the learning outcome through the use of more cognitive channels. In particular, the student will use not only memorization of color as a link to terms but also to connect a specific topic of study (“history”) with specific emotions. In this way, the teacher acquires an additional function as a color art therapy supervisor for the students, which is very likely to be highly effective for the class.

An important implication of the current study is the ability to use color coding for students with learning disabilities. Since the use of color accents in a presentation has been shown to increase student achievement, and since many of the respondents responded that the lesson was more engaging and intuitive for them, color coding can be approximated for teaching children with cognitive and mental disabilities. The assumption is consistent with an article by Robertson et al. (2021), in which color coding was a tool shown to be effective in teaching students with autism. Similar results were found in Ewoldt & Morgan (2017), who showed that color coding helps students with learning difficulties structure text and use grammar more intelligently. As a consequence, the findings of the current study, which are consistent with the literature, show the broad potential of color coding as a tool to optimize pedagogical practice.

In addition, the findings have long-lasting implications for curriculum development. Key findings from the experiment provided a clear indication that students’ range of academic skills (whether it be academic achievement, memory, perception of information, or engagement in learning) increased because of the use of color coding. Consequently, the use of this tactic is necessary to develop more optimized work programs and to improve overall learning effectiveness. Khan & Liu (2020) also showed that color cues led to improved memorization of English collocations for Chinese students, which means language performance increases. Among other things, Khan & Liu also concluded that the design of work programs should be changed to reflect the use of this color tool. Thus, the overall perspective is transparent: pedagogical sciences should use coding instructional materials as a science-based technique to improve student performance in both the short and long term.

Conclusion

The problem of finding the best academic practices to enhance the learning of English as a foreign language has important implications for the pedagogical sciences. Historically, many authors have contributed to the creation of new teaching techniques, and many have persisted in current versions of national educational systems. However, it is impossible not to see the apparent progress of education: many branches and areas of the educational process have undergone, and continue to undergo, permanent transformations aimed at improving the student experience and optimizing teaching resources. One of these innovations is the incorporation of technological solutions into the classroom environment, which has a number of advantages. In this sense, an attractive tool for the digitalization of the classroom is color highlighting, which allows specific words, fragments, or sentences in a presentation to be highlighted in a specific color. An experiment has proven that the presence of such color highlighting is a positive predictor of increased student achievement among ELL students. Specifically, there was a dramatic increase in the mean score of the experimental group compared at the starting point of the test and with the control group.

In addition, additional findings of this paper were the determination of the long-term effects of color coding on student achievement. It was shown that even one month after the research intervention, students in the experimental group-maintained progress, although their average exam score expectedly declined. Attractively, the standard deviation as a measure of data dispersion relative to the sample mean one month after the study intervention did not decrease as much compared to the control group: the drop rate was almost 1 to 6. In other words, a month after the training, students were more likely to answer the test correctly: this seems to be a consequence of the use of color coding. It is fair to admit, however, that it was not known precisely which aspect of academic performance was responsible for the higher result. It can only be speculated whether color coding had an effect on memory, engagement, or textual comprehension.

Additionally, it should also be emphasized that the results obtained are in good agreement with the academic literature. Numerous works have been shown to evaluate color coding in specific areas of pedagogy: the results of the experiment generally agree with the evidence of other authors. However, some works have been shown to contradict the results found. The reasons for this discrepancy could have been either a difference in the initial settings of the experiment (region, audience, age, proficiency level) or a difference in the metrics tested.

Limitations

The current research project has several limitations that hinder the generalization of the data to the population; most of them concern the methodological part. First, the sample generated was represented only by ELL female students from the KSA’s ELI. Thus, the findings are only valid for them, but it can be assumed that similar experiments will show similar results at other institutions and regions. Second, the initial level of all respondents was the same (pre-intermediate): therefore, one cannot reliably say whether the results would also be valid for students with other levels of language proficiency. Third, the sample was represented by a limited number of participants, and therefore scaling conclusions can also be problematic. This includes the qualitative portion of the study, where a semi-structured interview was conducted for only six participants from the experimental group. Fourth, the sample was formed according to a non-probability, convenience principle: this prevents it from being representative of the general population. Taking all of the described limitations of the study into account, it is essential to assume that conducting similar tests in other initial settings may lead to similar or identical results, which is entirely consistent with the analysis of the literature.

Future Research Prospects

The current project provided a foundation for expanding the possibilities for the use of color coding in learning and, in addition, further confirmed the evidence of previously published work by other authors. However, obtaining the findings of the present study is not enough to complete the entire project; instead, the proven effectiveness of color coding generates many promising directions for the development of research paradigms. Thus, it is of high academic interest to better define those aspects of an individual’s conscious activity that are susceptible to the effects of coding. In the present study, color has been shown to be important in increasing test performance, but it is now interesting to learn exactly what that performance is constructed of. Understanding these constructs will allow work programs to be more detailed and personalized.

Another promising direction for this study, which stems from its limitations, is to expand the sample, region, and level of English proficiency. It is necessary to expand the scope of the ELI to include universities and colleges in KSA and perhaps regions throughout the Gulf. A broader study would accurately reinforce the results of this project and perhaps uncover some new patterns related to sample demographics through cohort analysis. In addition, it is appealing to consider the effects of using color coding on non-English language learning industries. Academic sources have shown that coding makes sense in mathematics, so expanding the academic disciplines analyzed will yield extensive results. This includes comparisons between the results of native English speakers and ELLs.

Finally, another prospect for the development of this project is to increase the time to test the long-term perspectives of the study. The current experiment tested students’ knowledge after one month of instruction, which means it is worth testing the same effect for several groups after a more extended period of time, but within a semester. For example, after three and six months, the differences between the experimental and control groups can be traced. This will give an idea of how long-term the effects of color coding can be on ELLs.

References

Alhalabi, W. S., & Alhalabi, M. (2017). Color coded cards for student behavior management in higher education environments. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 18(1), 196-207.

Bakhshandeh, S., & Jafari, K. (2018). The effects of input enhancement and explicit instruction on developing Iranian lower-intermediate EFL learners’ explicit knowledge of passive voice.Asian-Pacific Journal of Second and Foreign Language Education, 3(1), 1-18.

Ben-Yehudah, G., & Eshet-Alkalai, Y. (2018). The contribution of text-highlighting to comprehension: A comparison of print and digital reading. Journal of Educational Multimedia and Hypermedia, 27(2), 153-178.

Chang, B., & Xu, R. (2019). Effects of colors on cognition and emotions in learning. Technology, Instruction, Cognition & Learning, 11(4), 1-6.

Chen, P., & Schmidtke, C. (2017). Humanistic elements in the educational practice at a United States sub-baccalaureate technical college.International Journal for Research in Vocational Education and Training, 4(2), 117-145.

Cui, L. (2018). MythBusters: Highlighting helps me study. Psychology in Action. Web.

Dzulkifli, M. A., & Mustafar, M. F. (2013). The influence of colour on memory performance: A review. The Malaysian Journal of Medical Sciences: MJMS, 20(2), 3-9.

Ewoldt, K. B., & Morgan, J. J. (2017). Color-coded graphic organizers for teaching writing to students with learning disabilities. Teaching Exceptional Children, 49(3), 175-184.

Hannon, M. A., & Raymond, R. A. (2018). Color coding of a sterile field to aid in recognition of visual cognition and learning. Nursing Education Perspectives, 39(6), 371-372.

Hernik, J., & Jaworska, E. (2018). The effect of enjoyment on learning [PDF document].

Khan, J., & Liu, C. (2020). The impact of colors on human memory in learning English collocations: Evidence from south Asian tertiary ESL students. Asian-Pacific Journal of Second and Foreign Language Education, 5(1), 1-10.

Lacy, C. E. (2020). Problem-solving versus solving problems from the ESL math teachers’ point of view[PDF document].

Li, K. L., Razali, A. B., Noordin, N., & Abd Samad, A. (2018). The role of digital technologies in facilitating the learning of ESL writing among TESL pre-service teachers in Malaysia: A review of the literature. Journal of Asia TEFL, 15(4), 1139-1145. Web.

Liu, Y., Zhang, M., Zhao, X., & Jia, F. (2021). Fostering EFL/ESL students’ language achievement: The role of teachers’ enthusiasm and classroom enjoyment. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 1-2.

Nilsson, P., & Eckert, A. (2019). Color-coding as a means to support flexibility in pattern generalization tasks [PDF document].

Nurdiansyah, D. M. R., Asyid, S. A., & Parmawati, A. (2019). Using color coding to improve students’ English vocabulary ability.Project (Professional Journal of English Education), 2(3), 358-363.

Pruisner, P. A. (1993). From color code to color cue: Remembering graphic information [PDF document].

Putwain, D. W., Becker, S., Symes, W., & Pekrun, R. (2018). Reciprocal relations between students’ academic enjoyment, boredom, and achievement over time.Learning and Instruction, 54, 73-81.

Qayumovich, R. M. (2021). The Poetics of Colors in English Poetry. Middle European Scientific Bulletin, 16, 22-26.

Robertson, C. E., Spooner, F., Wood, C. L., & Pennington, R. C. (2021). Color-coding print versus digital technology to teach functional community knowledge to rural students with autism and complex communication needs. Rural Special Education Quarterly, 40(4), 180-190.

Skulmowski, A. (2021). When color coding backfires: A guidance reversal effect when learning with realistic visualizations. Education and Information Technologies, 1-16.

Zorn, T., & McMurtrie, D. (2019). Color deficiency within the classroom. South Carolina Association for Middle Level Education, 21-25.