Introduction

A mental disorder is a severe mental or behavioral impairment that interferes with a person’s functioning. With the rising awareness of mental disease and increased amount of research exploring the topic, it appears that mental illnesses are significantly more common than one would think. The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (2018) reports that as many as 19.6% of adults in the US suffered from a mental health condition. 5.4% of adults could be categorized as having severe mental disorders (major depressive disorder, severe anxiety, severe post-traumatic stress disorder, and others) (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2018). Living with a mental illness presents a wide set of challenges for affected individuals one of which is physical comorbidities.

The poor physical health of people with severe mental disorders is a complex transdiagnostic problem that permeates age, gender, and ethnicity. The Lancet Psychiatry commission state that individuals with mental illness are at a higher risk of physical disease (Firth et al. 2019). The situation is aggravated by impeded access to adequate, timely health care. The Lancet Psychiatry claims that the medical and scientific communities have long been observing significant physical disparities across the spectrum of mental disorders (Firth et al. 2019). The phenomenon allegedly manifests itself no matter the income category of the country of residence (Maura & de Mamani, 2017). Mental patients in both developed and developing countries were disproportionately susceptible to physical disease.

At present, a plethora of studies seek to pinpoint the most common comorbidities in people with severe mental illnesses. An example of such study is a meta analytical review put together by Janssen, McGinty, Azrin, Juliano-Bult, and Daumit (2015). The researchers discovered that mental illness is often accompanied by or aggravates such conditions as: (1) overweight; (2) obesity; (3) hyperlipidemia; (4) hypertension; (5) diabetes mellitus; (6) coronary heart disease; (7) congestive heart failure; (8) cerebrovascular disease; (9) overall cardiovascular disease; (10) chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD); (11) kidney disease; (12) cancer; (13) hepatitis B; (14) hepatitis C, and (15) HIV.

The high rate of comorbidities accompanying mental illnesses seriously reduces the life expectancy of such patients (Firth et al. 2019). Aside from the report submitted by the Lancet Psychiatry commission, other recent studies on the subject matter also suggest the evidence of premature mortality in mentally ill individuals. For instance, Hjorthøj, Stürup, McGrath, and Nordentoft (2017) show that schizophrenia reduces average life expectancy by as many as 14.5 years across all continents. Besides, suffering from physical disease on top of handling a mental disorder puts a strain on an individual’s ability to function socially and economically (Funk, 2016).

The present literature review inquiries the causes of poor physical health of individuals with mental health disorders in community settings. The need for such a review is motivated by the prevalence of mental disorders and the grave impact of unaddressed comorbidities. Researchers seek to pinpoint the key factors contributing to the issue with the main focus on the United Kingdom. The paper provides a critique of six articles with both qualitative and quantitative methodology and discusses the implications of their findings.

Literature Search Strategy

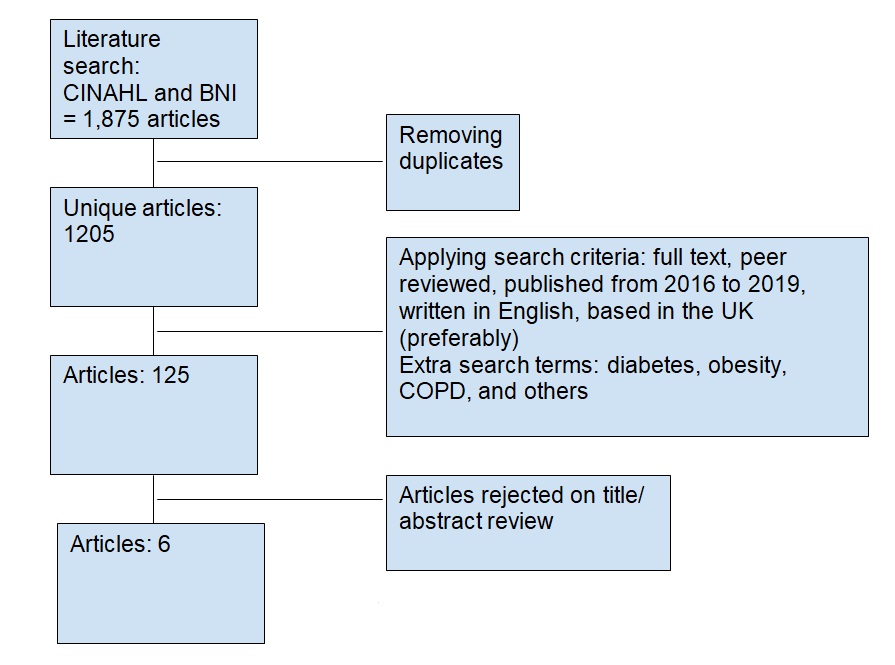

The literature search for the study was based on electronic databases such as British Nursing Index (BNI), Cumulative Index for Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), InterNurse, Medline, Science Direct, ASSIA, British Education Index, Education Abstracts and ERIC. Upon further investigation, the researcher discovered that CINAHL and BNI not only provided excellent primary sources but also were convenient and easy to access. Since the literature review was limited to six articles, there was no rationale for being superfluous in data search (Hart, 2018). However, the researcher still deemed it important to expand the scope of the literature search in the discussion section.

The researcher compiled a list of search and keywords based on the title of the study and the three research themes. Generic search using terms such as “poor physical health,” “severe mental illness,” “mental health patients,” and community returned the total of 1,876 articles. To overcome the difficulty of glossing over this body of evidence, the researcher decided to differentiate further. First, the results were narrowed to full text, peer review, written in English, and within the last 3 years (2016-2019). Second, the researcher used the common comorbidities found in mental patients (as discovered by Janssen et al. (2015)).

To make the search even more rigorous, the Boolean method was employed. it brought out the researcher’s imaginative skills for creation and use of words, terms, phrases and symbolic logical operators to arrive at broader but refined or fluid results. Some of Boolean logical operators/values includes the use of conjunction (and, &), inclusive/disjunction (or), negation (not), question marks (?) and asterix (*) to list but a few (Aliyu, 2017). Out of all these options, the most relevant to the chosen search strategy were question marks and asterisks. Further, the researcher read the abstracts of the studies left after the filtering. The writer critically assessed their validity and significance and jumped to the discussion section in some cases to evaluate how serious the limitations of the study were (Booth, Sutton & Papaioannou, 2016). Finally, the researcher was able to single out six articles that were recent and relevant to the topic. The literature search strategy is presented visually in the image below.

Literature Review

Underdiagnosing Comorbidities

The first step to effective treatment is making a sound diagnosis. unfortunately, it seems that it is not the case for many mental patients. Cook et al. (2016) argue that people with mental illnesses experience multiple health disparities and increased medical morbidity. The phenomenon persists in even in countries whose citizens enjoy universal access to healthcare. Cook et al. (2016) claim that there is not enough evidence about the prevalence of medical comorbidities in demographics with a mental health condition and receiving health services in outpatient settings.

The aim of the study conducted by Cook et al. (2016) was to calculate the prevalence of eight most common medical comorbidities: (1) obesity, (2) hypertension; (3) diabetes; (4) smoking; (5) nicotine dependence; (6) alcohol abuse; (7) drug abuse; (8) coronary heart disease. Apart from those conditions, Cook et al. (2016) deemed it important to assess self-reported health competencies, medical conditions, and health service utilization. The need for the study is validated by the danger of underdiagnosing comorbidities. The researchers state that without regular screenings, patients with mental illnesses might be unmotivated to seek treatment or take preventive measures.

The researchers recruited 457 (464 contacted in total, seven refused) mentally ill patients in four US states: New Jersey, Illinois, Maryland, and Georgia. The eligibility criteria included being of age, the ability to give informed consent, English speaking, and participation in a community mental health program. The diagnosis needed to be recognized by DSM and indicate a moderate to severe mental impairment. For the sake of the ethical rigor, the researchers ensured confidentiality and anonymity. They took measures to verify that participants’ mental health status did not interfere with their ability to make well-informed decisions. The latter was especially important since some mental conditions prevent affected individuals from making sound decisions. To avert such situations, Cook et al. (2016) inquired those who volunteered about their understanding of the purpose of the study.

During the screenings administered in the four aforementioned states, the researchers and invited medical staff achieved two goals. First, they made a differentiated clinical diagnosis for each patient; second, they measured participants’ attitudes toward their own health using a variety of questionnaires. Lastly, it was essential to not only identify issues at hand but also assess health risks, which was done through measuring body mass index (BMI) based on height and weight; blood pressure; blood glucose, and other metrics. The data was subject to descriptive statistical analysis (prevalence, means, medians, and others). Random regression analysis helped to pinpoint changes in participants’ pre- and post-screening attitudes.

The data analysis has yielded the following results with regards to the prevalence of the explored morbid conditions: obesity (60%), hypertension (32%), diabetes (14%), smoking (44%), nicotine dependence (62%), alcohol abuse (17%), drug abuse (11%), and coronary heart disease (10%). The results indicated a higher prevalence as compared to the official health information. This implies that patients with mental illnesses indeed suffer from insufficient diagnosing, which may be worsening their quality of life. As expected, Cook et al. (2016) noticed significant positive changes in how patients perceived their own health efficacy after participating in health screening. At post-test, participants reported higher evaluations of their degree of competence in performing health practices. Lastly, Cook et al. (2016) observed an enhanced degree of internal control over one’s health.

The study had some serious caveats: firstly, the sample was not representative of broader populations. Secondly, Cook et al. (2016) did not recruit a control group to truly measure the effect of the intervention. Despite the limitations of the study, the findings shared by Cook et al. (2016) are definitely of value for nurses working with mental patients. Probably, one major implication that practitioners should pay attention to is the effect of a simple health screening. The obvious positive consequence for patients is actually learning about their comorbidities. The less apparent impact is the encouragement they receive to maintain their health and address their issues.

Non Adherence to Medication

Another serious barrier to physical and mental health is patients’ compliance and commitment to the treatment plan. While being able to access medical service is integral to relief and recovery, the process is a two-way street. Medical professionals play an important role in enhancing patients’ quality of life; however, their best efforts to help may prove to be futile if the patient does not adhere to recommendations. Hickling, Kouvaras, Nterian, and Perez-Iglesias (2018) investigated exactly why some patients refuse to take medications even though the consequences of such a decision might pose a threat to their health. The aim of the study is to identify the association between the attitudes of patients with psychosis (independent variable) and their adherence level (dependent variable).

The study’s significance is validated by the impact that adherence and non adherence to medications have on patients’ health outcomes. Other researchers concur with the rationale provided by Hickling et al. (2018): for instance, Wouters et al. (2016) show that non adherence decrease the likelihood of a positive outcome in the long-term. Hickling et al. (2016) state that exploring the issue of non-adherence is especially important when it comes to psychosis. As a whole, antipsychotic drugs are highly efficient; however, attaining and maintaining adherence is challenging for both patients and healthcare workers (Hickling et al. 2016). The researchers explain that episodes of psychosis are disruptive to a person’s life and may lead to the neglect of physical health among other consequences.

Participants were recruited at random from COAST Early Intervention in psychosis service, South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust (SLaM). Researchers approached patients attending the outpatient clinic in person. The eligibility criteria for an interview included being of age (18 years and older), having an official diagnosis (psychosis), and being prescribed antipsychotic medication. To ensure the ethical rigor of the study, the researchers reassured the participants that the data collected will not be accessible by their clinicians. Aside from that, the researchers ensured total confidentiality and anonymity as well as participants’ ability to provide informed consent. The project was approved by SLaM NHS Foundation Trust, a UK-based ethical board.

In order to measure the dependent and independent variables, Hickling et al. (2016) selected three externally validated questionnaires. Self-reported adherence was evaluated using the Selwood Compliance Scale that consists of four statements regarding medication taking behaviour. Based on the responses to the first questionnaire, patients were classified as whether adherent or non adherent. Beliefs about antipsychotic medications were measured with the Beliefs about Medicines Questionnaire (BMQ). The BMQ assesses two dimensions of medication use: personal (in terms of necessity and concern) and general (in terms of harm and overuse). Lastly, Hickling et al. (2016) explored whether patients with psychosis believed that they were provided with sufficient, exhaustive information using Satisfaction with Information about Medicines Scale (SIMS).

The data was analyzed using SPSS, and the following methods were employed: Student’s t-tests (for continuous variables) and Pearson’s chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests (categorical variables). To identify the main predictors of adherence to antipsychotics binary logistic regression was used. One-way ANOVA (analysis of variance) was administered to identify the effects of the BMQ categories (necessity, concerns, harm, and overuse) on adherence.

The results of data analysis were comprehensively demonstrated in tables and plots. Hickling et al. (2016) discovered that two-thirds (66%) of patients could be classified as adherent while one-third (34%) showed significant non-adherence. Interestingly enough, such factors as gender, employment, and living separately or with a family did not impact the likelihood of adherence (Hickling et al. 2016). However, what apparently made a difference is age: younger patients were more to ignore their treatment plan. As for the participants’ beliefs, one category that strongly correlated with adherence was concerns about one’s health. Lastly, adherent patients expressed more satisfaction with the information provided about antipsychotic medications as compared to non-adherent patients.

The study had some serious limitations: firstly, due to the study design, Hickling et al. (2016) were unable to pinpoint causal relationships. Another limitation concerns the major pitfall of any study that relies on self-reported data: there is hardly any way to check whether the participants were honest. Lastly, as Hickling et al. (2016) admit non-adherent patients are less likely to participate in research, therefore, the sample itself might have not been exactly representative. Despite all the aforementioned limitations, the study is still of value to practicing nurses who deal with mentally ill patients. One practical implication that they might want to use is that complete and comprehensive information about medication might promote adherence in patients. As a result, they will relieve their symptoms and will be able to take care of their physical health as well.

Stigma

For individuals with mental disease, timely intervention and self-care habits are essential for recovery or at least a relief of burdening symptoms. Mantovani, Pizzolatti, and Edge (2017) investigate the issue of stigma as one of the key barriers to receiving medical help and treating mental disorders. The researchers define stigma as an “attitude that is deeply discrediting (Mantovani, Pizzolatti & Edge, 2017).” Essentially, stigmatization is a psychological process of deriving the feelings of shame and inadequacy in individuals whose health status presents certain challenges for social functioning. Mantovani, Pizzolatti, and Edge (2017) explain that stigma occurs at two interconnected and mutually reinforcing dimensions: personal and social.

Self-stigma, or personal stigma, is internalized negative beliefs about individuals with stigmatized attributes. For instance, a person who was raised to believe that it is shameful to suffer from a mental illness may be confronted with an additional difficulty in battling the disease. Social stigma, on the other hand, is produced collectively and draws upon common, often misguided beliefs. An example of social stigma pertaining to the subject matter would be a stereotype that all mentally ill people are inherently dangerous. As one may readily imagine, once this belief becomes part of self-stigma, the affected individual might be extremely reluctant to seek help in order not to proclaim themselves “dangerous.”

In the United Kingdom, stigma reduction has become one of the public health priorities, which is even reflected in a number of policy documents. At present, eradication of mental health stigmatization is seen as a requirement for ensuring social justice and equality. The need for the study is also motivated by the importance of reaching out and contacting mental health specialists in the first place. Maintaining a good physical health is extremely difficult if a patient is struggling with the symptoms of his or her mental condition on a daily basis. For instance, Badcock, Davey, Whittle, Allen, and Friston (2017) write that having a major depressive episode may be compared to having a mild cognitive impairment. According to Badcock et al. (2017), an untreated mental disorder interferes with long-term planning, memory, and decision-making. These three mental faculties are essential to making healthy choices and upholding positive habits.

Mantovani, Pizzolatti, and Edge (2017) narrow down the scope of their qualitative research to African-descended communities in the UK. The aim of the study is to investigate the complex ways in which stigma influences help-seeking for mental illness in the said demographic cohorts. To achieve the research goals, Mantovani, Pizzolatti, and Edge (2017) recruited 26 African descendents from eight geographically adjacent faith-based organizations (FBOs) of different Christian denominations. The organizers from the said FBOs codesigned the information material explaining the purpose of the study to the respective participants and ensured confidentiality and anonymity.

The semi-structured interviews have shown that African communities in the UK indeed suffer from personal and social stigmatization of mental health issues. Among common themes identified in the collected text data were the themes of weakness and self-shame. Another common theme was the lack of acceptance in African communities and their ostracization of those in need of help for their mental disease. The obvious strength of the analyzed study is its novelty: it is arguably the first precedent of meta analysis on quite a narrow topic. The main limitation is the modest sample size and researchers’ inability to recruit individuals not from FBOs due to time constraints. Mantovani, Pizzolatti, and Edge (2017) are looking forward to more studies that could build on the methods and findings of the present study. Nevertheless, the study started an important discussion about the stigmatization of mental illnesses. Health practitioners need to be aware that both mental and physical recovery in patients with mental disorders start with their intention to get better and lack of shame.

Obesity

In their quantitative correlation study, Jonikas et al. (2016) explore the factors influencing the development of overweight and obesity in mentally ill persons. The researchers explain the importance of this research area by citing recent global statistics on obesity. Jonikas et al. (2016) state that the fact that one-third of the world’s adult population is either overweight or obese is indicative of global crisis. The authors refer to reliable sources showcasing the association of obesity and cardiovascular diseases that have become the number one cause of death in the majority of countries (Jonikas et al. 2016). It is argued that mentally ill individuals are more prone to being obese than general populations. Jonikas et al. (2016) speculate that severe mental disorders interfere with the maintenance of a healthy lifestyle and do not allow affected individuals take timely measures. The aim of the study by Jonikas et al. (2016) was to discover the association between obesity (dependent variable) and gender, clinical factors, and medical comorbidities (independent variables) in mentally ill patients.

The data was collected from 457 (464 contacted in total, seven refused) mentally ill patients in four US states: New Jersey, Illinois, Maryland, and Georgia. The eligibility criteria included being of age, the ability to give informed consent, English speaking, and participation in a community mental health program. The diagnosis needed to be compliant with DSM and indicate a moderate to severe mental impairment. The study can be recognized as ethically rigorous: the researchers ensured confidentiality and anonymity. They took measures to verify that participants’ mental health status did not interfere with their ability to make well-informed decisions.

Participants were invited to screening stations where they were administered the following tests: body mass index (BMI), blood pressure, non-fasting lipid profile, risk for alcohol and drug abuse, blood glucose profile, and some others (Jonikas et al. 2016). The validity of the data collection is verified by the fact that screening staff was specifically trained in methods for administering the aforementioned tests. The collected data was processed using hierarchical ordinary least squares regression analysis; the researchers made sure to control for psychiatric, smoking, health insurance, and demographic factors. Jonikas et al. (2016) presented the discovered multivariate associations in tables, stating the results for p<0.001, p<0.01, and p<0.05.

As a result, Jonikas et al. (2016) were able to confirm all the research hypothesis Namely, they discovered that women with mental illnesses were more likely to be obese as compared to their male counterparts. In the discussion section, Jonikas et al. (2016) provided a few possible explanations for this association. Firstly, it is possible that women with mental illnesses had lower levels of activity than men. Secondly, they might have gained weight due to hormonal transitions. Lastly, Jonikas et al. (2016) put forward the idea that since female mental patients had a higher likelihood of experiencing a childhood trauma, they might have developed an eating disorder leading to obesity. Some of the other associations discovered by the researchers concern not completing high school, diabetes, and hypertension.

The main strength of the study lies in the discovery of actual factors behind obesity in mental patients. However, there are certain limitations: the major threat to validity is the sampling method that resulted in recruiting participants that might not be exactly representative of broader populations. The second limitation undermining the value of the study is researchers’ inability to collect more background data on participants’ family history and dietary habits. Nevertheless, the findings of the study and especially the recommendations provided by Jonikas et al. (2016) may contribute positively to adult nursing practice. They suggest that optimal physical health promotion will require targeting populations at risk.

The Lack of Physical Activity

When discussing strategies to overcome the issue of poor physical health in mental patients, one may find it useful to focus on modifiable factors. One of such factors is physical activity that has been found integral to preserving heart health and preventing such conditions as hypertension and cardiovascular disease (Vancampfort, Stubbs, Venigalla, & Probst, 2015). In their quantitative cross-sectional study, Vancampfort et al. (2015) seek to pinpoint motivational problems in patients with mental illnesses that prevent them from doing sports and being active. The researchers explain the need for such a study by soaring rates of premature mortality in mentally ill individuals: both due to natural causes and cardiovascular disease. Vancampfort et al. (2015) argue that investigating motivational deficits might help health practitioners to reach out to more patients with mental disorders and convince them to make healthier choices. At the beginning of the paper, the researchers speculate that it might be the overbearing symptoms of mental disease that do not let patients make their physical health a real priority.

The data was collected from 257 patients residing in the United Kingdom; no pilot study was administered. The recruitment of participants took place in two waves: first, patients with bipolar and affective disorder were invited; second, patients with depression and schizophrenia. The eligibility criteria included: a) an official diagnosis in compliance with DSM; b) ability to concentrate for 20-25 minutes to complete the survey. Vancampfort et al. (2015) combined two widely used questionnaires: the Behavioral Regulation in Exercise Questionnaire (BREQ) and International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ). The participants were handled by trained psychiatrists who did not partake in research. Vancampfort et al. (2015) ensured the ethical rigor of the research by receiving approval of 15 local ethical committees. Aside from that, the researchers ensured confidentiality and gained informed consent before proceeding with the survey.

The collected data was explored using multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) for identifying the differences between diagnostic groups. Student’s t-test was administered for exploring the differences between men and women, various age groups, and individuals with varying educational background (Vancampfort et al. 2015). The findings have shown that patients with affective and bipolar disorders were more likely to have the so-called introjected motivation than patients with schizophrenia. Introjected motivation is a person’s drive to achieve something due to external pressure that becomes internalized over time. The researchers discovered that individuals had the most prominent motivational deficits at the early stages of change. Interestingly enough, such factors as age, gender, ethnicity, and education level did not influence how motivated people were. Another significant finding concerned with the impact of extrinsic and intrinsic motivation. Individuals with intrinsic motivation were more active while those motivated extrinsically were more likely to withdraw from physical activities. In summation, Vancampfort et al. (2015) were able to meet the research objectives and come to meaningful conclusions.

For all its advantages, the study was not devoid of significant limitations, which is why its findings should be treated with caution. Firstly, Vancampfort et al. (2015) state that both questionnaires (BREQ and IPAQ) are considered reliable and comply with the international standards. However, the participants might have submitted distorted information because the design of the study essentially implies self-reporting. The second limitation is the exclusion of such an important criteria as medication use, which might have also shaped participants’ motivational patterns. Lastly, Vancampfort et al. (2015) did not collect any background information on participants, for example, about their smoking habits. Despite the aforementioned limitations, health practitioners may still come to meaningful conclusions regarding the results of the study. As Vancampfort et al. (2015) state themselves, it is important to pay attention to a person’s motivation type when encouraging them to take up a healthier lifestyle. Health practitioners can gain insights into the nature of mental illness and motivation to better understand the unwillingness of some patients to do sports.

Smoking

Aside from neglecting physical exercise, another lifestyle choice that might be impacting mental patients’ health negatively is smoking. Szatkowski and McNeill (2015) explored the diverging trends in smoking behaviors with regards to the mental health status. The researchers claim that while the smoking habit has been on decline globally in the last ten years, individuals with mental disorders still show higher rates of smoking. The aim of the study by Szatkowski and McNeill (2015) was to understand the dynamics of smoking prevalence in two distinct groups of people: mentally healthy and mentally ill. The working hypothesis for the study was the following: the decline in smoking habits would be more pronounced in individuals without mental health issues as opposed to those who have them. The need for a study with such a design and research questions is motivated by the negative impact that smoking has on human health (Szatkowski & McNeill 2015). Apart from Szatkowski and McNeill (2015), other researchers spoke exhaustively about the adverse effects of smoking. Onor et al. (2017) and Kowalzciuk et al. (2017) enlist such conditions as lung cancer, COPD (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease), decreased male fertility, pregnancy complications and preterm birth as being associated with smoking.

Szatkowski and McNeill (2015) collected data from survey responses from adults (16 year and older) residing in England. Aside from the age, another key eligibility criteria for participating in the study was participation in the Health Survey for England from 1993 through 2011. As Szatkowski and McNeill state, the database gave them access to more than 11,000 profiles per year. The Health Survey allowed them to categorize the participants with self-reported longstanding mental illness and those who recently used psychoactive medication as mentally disordered. The data was analyzed using simple linear regression, which allowed Szatkowski and McNeill (2015) to quantify annual changes. Data analysis investigated the dynamics of the smoking habit, daily consumption as well as respondents’ readiness for smoking cessation. The results were comprehensively presented in tables that included correlation coefficients and confidence intervals.

The findings of the study confirmed the initial research hypothesis, which means that Szatkowski and McNeill (2015) were able to achieve their research goals. The main findings suggested that the respondents without a longstanding mental illnesses showed more pronounced declines in smoking prevalence (-0.5% annually at a 95% confidence interval). Aside from that, the mentally healthy study participants were more likely to decrease their daily consumption (-0.14% annually at a 95% confidence interval). The respondents who reported a mental disorder did not demonstrate similar tendencies: in fact, they continued their smoking habit with the same intensity throughout the years. Interestingly enough, those taking psychoactive medication to fight their disorder were able to control their habit and reduce their consumption. The last key result worth mentioning is the same level of desire to quit in both mentally ill and mentally healthy patients.

The conclusions made by Szatkowski and McNeil (2015) are of value for health practitioners dealing with mentally ill patients and can be translated into practice. Nurses should understand that patients with mental disorders are more likely to develop a smoking habit and have more difficulties quitting it. As Szatjowski and McNeill (2015) write, there are a few explanations for this phenomenon with the most widely recognized being that individuals with a psychiatric diagnosis might be using smoking as a coping strategy. In nursing practice, it is essential that healthcare workers pinpoint the actual reasons on a case-to-case basis. However, the findings of the study should be approached with caution. The researchers admit that there are a few limitations that might have been undermining to the study’s validity. Firstly, it was impossible to tell whether those who self-reported a mental illness had an actual diagnosis. Secondly, the design of the health survey made it impossible to single out specific groups, for example, schizophrenic patients, bipolar patients, and others.

Discussion

The literature review has demonstrated the complexity of the issue of poor physical health in patients with mental illnesses. It has become evident that the problem exists and persist at three levels: at the level of the healthcare system as a whole, medical staff, and patients themselves. The study by Cook et al. (2016) implies that mental patients are routinely underserved: they have multiple undiagnosed comorbidities that worsen their quality of life. Inferring the findings on the UK, one may also add that here the situation is aggravated by the politics of austerity that reduce social benefits (Stuckler, Reeves, Loopstra, Karanikolos & McKee, 2017). Stuckler et al. (2017) have shown that austerity has caused a search in mental disease rates and even correlated positively with suicide rates. This implies that the national healthcare system needs to undergo a transformation that would accommodate the most vulnerable demographics. The intervention conducted by Cook et al. (2016) could lay a foundation for the future change. Community-based screenings are not difficult to organize, and the positive effect lingers for a long time.

Gopee and Galloway (2017) and Pilgrim (2019) argue that top-down policies regarding promoting mental health would indeed be a solid step forward. Yet, they would not come to fruition without leadership and change management at the hospital level. Hayes (2018) highlight the need for flexibility to tackle the uncertainty in healthcare, for which it is imperative that health workers know how to react and respond adequately. Proctor et al. (2017) claim that health care is in dire need of evidence-based approaches: they that would translate the recent scientific findings like those cited in this paper into practice. Evidence-based medicine has a chance to be sustainable: it teaches medical staff critical thinking and creative problem solving. As mental health issues gain more traction in British society, healthcare workers shall stay on top of events and be able to address the issues in a timely manner.

The literature review helped the researcher once again realize the importance of therapeutic communication. As Brownie, Scott, and Rossiter (2016) write, the complexity of therapeutic communication in chronic care is explained by the exposure and vulnerability that patients experience when receiving medical help. A healthcare worker assumes a position in which they have enough power and leverage to motivate a patient to maintain a healthy lifestyle or give up on such attempts altogether (Ford, Thomas, Byng & McCabe, 2019). One of the best approaches is described by Schwartz et al. (2017): the authors claim that medical specialists need to look beyond the disease and see a unique person behind it. This mindset should serve as a foundation of the so-called patient-centered collaboration. Within this framework, a healthcare worker does not make top-down decisions for patients; instead, the latter are equally involved.

For instance, Hickling et al. (2018) discovered that one of the reasons why patients fail to stick to the treatment plan was that they were concerned about side effects and did not feel like they had exhaustive information about medication. Patient-centered collaboration proposed by Schwartz et al. (2017) could help to promote self-agency in patients. If they are informed about the effects of medication and benefits of therapy, they would allegedly feel more responsible for their health. Stevens et al. (2017) describe the social identity approach to health that akin to the patient-centered approach, puts an emphasis on the individual factors. Stevens et al. (2017) address the issue of low levels of physical activity in mental patients, which was also observed by Vancompfort et al. (2015). The researchers claim that low motivation un unwillingness to make healthier choices come down to cognitive factors, motivation, and attitudes. One solution to this would be to help mental patients to transition from their individual identity to group identity by joining exercise groups. Stevens et al. (2017) and Mendoza-Vaskonez et al. (2016) argue that the team spirit and leadership could make a difference for poorly motivated patients.

Another implication for healthcare workers is the need to tackle the issue of bad habits in patients with mental disease. As this literature review has shown, smoking remains prevalent in adults with mental disorders in the UK, despite the overall decline over the last two decades. Given that chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) belongs to the long list of severe comorbidities common in mental patients, smoking is a habit that needs to come to cessation. The question arises as to how healthcare workers could influence patients in a way that they would act on their intentions and commit to their promises to quit. Coronado-Montoya et al. (2016) show that mindfulness exercises could be used for successful mental health interventions. Mindfulness is a psychological concept that denotes a person’s ability to be conscientious, to know oneself, and be aware of one’s thoughts and feelings. In relation to bad habits, mindfulness could help patients to realize what triggers their urges to indulge. With time, they could come up with more sustainable pathways toward emotional gratification without harming themselves.

Lastly, the literature review implies that healthcare workers need to be good, evidence-based predictors. Jonikas et al. (2016) have demonstrated that some factors predispose mental patients to have poor physical health. Building on findings like those cited in this paper, nurses could try and develop their own strategies to singling out groups that are more at risk of having comorbidities. For instance, in alignment with what Jonikas et al. (2016) discovered, nurses could be more persistent with promoting physical activity in women with mental disease. Surely, promotion should not highlight the “otherness” of a group at risk as it might lead to stigmatization. In any case, healthcare workers need to rely on the key principles of therapeutic communication and treat patients with respect.

Summation / Conclusion with Recommendation

The present literature review has demonstrated apparent physical health disparities and increased premature mortality rate in patients with mental illnesses. It is evident that the issue of poor physical health is a complex one, with a plethora of underlying factors and reasons. Patients with mental disease are routinely underdiagnosed, which leads to the aggravation of existing comorbidities. Stigmatization, or discreditation of their physical and mental state, prevents them from reaching out to health specialists. On top of that, many mental patients show non-adherence to medications, which impedes their recovery. Lastly, some of the other factors responsible for poor physical health are obesity, lack of physical activity, and harmful habits such as smoking. The problem can only be solved if both sides – healthcare workers and patients – make a conscious effort to bring about the needed change. Regular screening should become the norm to prevent the development of comorbidities in mental patients. The latter in turn should be more conscientious about their health. The process needs to be mediated by healthcare workers who could encourage patients and provide them with necessary information.

Reference List

Aliyu, Muhammad Bello 2017, ‘Efficiency of Boolean search strings for Information retrieval’, American Journal of Engineering Research, vol. 6, no. 11, pp. 216-222.

Badcock, Paul B, Davey, Christopher G, Whittle, Sarah, Allen, Nicholas B & Friston, Karl J 2017, ‘The depressed brain: an evolutionary systems theory’, Trends in Cognitive Sciences, vol. 21, no. 3, pp. 182-194.

Brownie, Sharon, Scott, Robin & Rossiter, Rachel 2016, ‘Therapeutic communication and relationships in chronic and complex care’, Nursing Standard, vol. 31, no. 6, p.54.

Booth, Andrew, Sutton, Antea and Papaioannou, Diana 2016, Systematic approaches to a successful literature review, Sage, Newbury Park.

Coronado-Montoya, Stephanie et al. 2016, ‘Reporting of positive results in randomized controlled trials of mindfulness-based mental health interventions’, PloS one, vol. 11, no. 4.

Gopee, Neil & Galloway, Jo 2017, Leadership and management in healthcare, Sage, Newbury Park.

Firth, Joseph et al. 2019, ‘The Lancet Psychiatry Commission: a blueprint for protecting physical health in people with mental illness’, The Lancet Psychiatry, vol. 6, no. 8, pp. 675-712.

Ford, Joseph, Thomas, Felicity, Byng, Richard & McCabe, Rose 2019, Exploring how patients respond to GP recommendations for mental health treatment: an analysis of communication in primary care consultations, Web.

Funk, M 2016, Global burden of mental disorders and the need for a comprehensive, coordinated response from health and social sectors at the country level, Web.

Hart, Chris 2018, Doing a literature review: Releasing the research imagination. Sage, Newbury Park.

Hayes, John 2018, The theory and practice of change management, Palgrave, London.

Hayes, Josepth F et al. 2016, ‘Self-harm, unintentional injury, and suicide in bipolar disorder during maintenance mood stabilizer treatment: a UK population-based electronic health records study’, JAMA psychiatry, vol. 73, no. 6, pp. 630-637.

Hickling, Lauren M, Kouvaras, Stefanie, Nterian, Zaklin & Perez-Iglesias, Rocio 2018, ‘Non-adherence to antipsychotic medication in first-episode psychosis patients’, Psychiatry Research, vol. 264, pp. 151-154.

Hjorthøj, Carsten, Stürup, Anne Emilie, McGrath, John J and Nordentoft, Merete 2017, ‘Years of potential life lost and life expectancy in schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis’, The Lancet Psychiatry, vol. 4, no. 4, pp. 295-301.

Janssen, Ellen M, McGinty, Emma E, Azrin, Susan T, Juliano-Bult, Denise & Daumit, Gail L 2015, ‘Review of the evidence: prevalence of medical conditions in the United States population with serious mental illness’, General Hospital Psychiatry, vol. 37, no. 3, pp.199-222.

Jonikas, Jessica A et al. 2016, ‘Associations between gender and obesity among adults with mental illnesses in a community health screening study’, Community Mental Health Journal, vol. 52, no. 4, pp. 406-415.

Kowalczyk, William J et al. 2017, ‘Predictors of the perception of smoking health risks in smokers with or without schizophrenia’, Journal of Dual Diagnosis, vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 29-35.

Onor, IfeanyiChukwu O et al. 2017, ‘Clinical effects of cigarette smoking: epidemiologic impact and review of pharmacotherapy options’, International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, vol. 14, no. 10, p. 1147.

Proctor, Enola et al. 2015, ‘Sustainability of evidence-based healthcare: research agenda, methodological advances, and infrastructure support’, Implementation Science, vol. 10, no. 1, p. 88.

Maura, Jessica & de Mamani, Amy W 2017, ‘Mental health disparities, treatment engagement, and attrition among racial/ethnic minorities with severe mental illness: a review’, Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings, vol. 24, no. 3-4, pp. 187-210.

Mantovani, Nadia, Pizzolati, Micol & Edge, Dawn 2017, ‘Exploring the relationship between stigma and help‐seeking for mental illness in African‐descended faith communities in the UK.’, Health Expectations, vol. 20, no. 3, pp.373-384.

Mendoza-Vasconez, Andrea S et al. 2016, Promoting physical activity among underserved populations, Current Sports Medicine Reports, vol. 15, no. 4, p. 290.

Pilgrim, David 2019, Key concepts in mental health, SAGE Publications Limited, Newbury Park.

Sendt, Kyra-Verena, Tracy, Derek Kenneth & Bhattacharyya, Sagnik 2015, ‘A systematic review of factors influencing adherence to antipsychotic medication in schizophrenia-spectrum disorders’, Psychiatry Research, vol. 225, no. 1-2, pp. 14-30.

Schwartz, David D et al. 2017, ‘Seeing the person, not the illness: promoting diabetes medication adherence through patient-centered collaboration’, Clinical Diabetes, vol. 35, no. 1, pp. 35-42.

Stevens, Mark et al. 2017, ‘A social identity approach to understanding and promoting physical activity’, Sports Medicine, vol. 47, no. 10, pp. 1911-1918.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration 2018, Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: results from the 2018 national survey on drug use and health, Web.

Stuckler, David, Reeves, Aaron, Loopstra, Rachel, Karanikolos, Marina & McKee, Martin 2017, ‘Austerity and health: the impact in the UK and Europe’, European Journal of Public Health, vol. 27(suppl_4), pp. 18-21.

Vancampfort, Davy, Stubbs, Brendon, Venigalla, Sumanth Kumar & Probst, Michael 2015, ‘Adopting and maintaining physical activity behaviours in people with severe mental illness: the importance of autonomous motivation’, Preventive Medicine, vol. 81, pp. 216-220.

Wouters, Hans 2016, ‘Understanding statin non-adherence: knowing which perceptions and experiences matter to different patients’, PloS one, vol. 11, no. 1.