Introduction

The history of Australia and its architecture are closely interconnected, showing a similarity in events and tendencies exhibited by the majority of movements. The colonial past of the country presupposed the influence that the United Kingdom had on the state’s early construction projects. At the beginning of the twentieth century, Australia’s economy was beginning to stabilise, giving the country a reason for improving its cities. However, the British architectural firms that had their offices in Australia were reluctant to supply the developing country with similar attention to quality and detail that was expected of them in the UK. The resources were delivered to Australia rather than produced there, further delaying its speed of innovation. With the beginning of World War I, the country’s prospects of building a new capital were changed and stalled, leaving the country’s architecture in a suspended state for several years.

The urban nature of Australia, however, quickly returned the interest for city planning to creators. The architecture of Melbourne, one of the most populous cities in the state, also saw many architects and movements throughout the years, combining both old and new styles and mainstream and rebellious tendencies. While the modernist movement brought many skyscrapers into the city, Melbourne managed to preserve buildings distinctly different from the constructions made primarily from metal and glass. In the comparison of international modernism, represented by many mainstream tendencies and the pluralism of cultures and visions seen in a variety of styles from Victorian architecture to art deco, multiple architects can be mentioned.

First of all, the contribution of Walter Burley and Marion Mahony Griffin, first, to the design of Canberra, then, to the architecture of Melbourne, cannot be overlooked. The duo of American architects created a number of buildings that remain a part of the city to this day, including the Newman College and the Capitol Theatre. Second, the works of Kevin Borland who moved from the International Modernist style to Brutalism also need to be mentioned. Finally, the contribution of the architectural firm Edmond and Corrigan and its originators to the city’s national identity is also significant to the appearance of Melbourne. These creators, while designing buildings and plans in different styles and adhering to a variety of movements, have one characteristic in common. Their approach to the national and regional identity and the search for a more organic alliance between Melbourne’s culture, history, nature, and urban life separate their buildings from the mainstream architecture of the city.

The Griffins

At the beginning of the twentieth century, Walter Burley and Marion Mahony Griffin came to Australia from the United States to work on the future capital of the country, Canberra. Their winning contribution to the competition for the best plan presented a vision of a future for Australia to which the architects were determined to stick. However, multiple constraints, both political and economic, did not allow the couple to bring their initial plans to completion and left the architects disenchanted to working in Canberra. The Griffins, however, remained popular in Australia due to their groundbreaking and unique suggestion, which allowed them to continue designing for the country. A number of their most notable projects are represented in the architecture of Melbourne where they have created the Newman College and the Capitol Theatre. However, some of the buildings did not survive and were destroyed by fire or demolished.

In 1915, Walter Burley Griffin was asked to redesign Vienna Cafe located in Melbourne. In 1916, the place was reopened as Cafe Australia. The design of the new version was different from the original with its completely remodelled façade and interior. The magazine observing the cafe after its opening described it as ‘ultra modernistic’ and ‘bizarre’, noting its ‘old-fashioned’ and ‘sombre’ furnishings. The combination of styles, namely European Art Noveau and the Chicago School, used by the architect combined modernistic aspects and informal details, presenting a cafe with a vaulted ceiling, hidden cove lighting, and lace ornaments (Figure 1).

The cafe’s further remodels tried to capture Griffin’s initial ideas and left his ceiling and balcony designs unchanged. The combination of multiple styles in one design revealed Griffin’s lack of desire to follow a specific set of rules developed for one movement. The use of rough black granite and blue tiles for the façade and white ornamented details for the interior differed from the guidelines for both a more classical and contemporary looking design. The interior was also not made in one style, using both decorated columns and a modernistic balcony with glazed doors.

The next project of the architects still stands as one of his main accomplishments. The buildings of the Newman College were designed by the Griffins during the same period as the cafe discussed earlier. The University of Melbourne delegated a large area for the college to be built, allowing the architect to reserve a large space for recreation as the property resembled a meadow more than an urban piece of land. The final version of the design included two large buildings designated for a library and a dining hall, both in the form of rotundas (Figure 2). These structures were situated on the opposite sides of the area’s edge. The buildings were connected to long wings of student rooms, one for women and one for men. The chapel of the college was placed in-between, closing the way to the open area.

The rotundas were made to be spacious with their triangular-shaped ribs and high domed ceilings. The corridors and rooms of the other buildings were almost medieval in nature – tight spaces, low ceilings and narrow paths. The contrast of these two concepts resulted in a unique work representing the Griffins’ style. The buildings did not, however, follow all rules of an older design, implementing less standardised structures and giving less attention to the academic idea of stylisation. The combination of columns adorned similarly to the ornaments in the cafe and rough stone used for decoration presented a view that varied considerably from other buildings in the city.

As can be seen in the previous paragraphs, the Griffins’ contribution to the architecture of Melbourne did not adhere to the guidelines of a particular style which could sometimes be expected by the movements’ followers. The architects combined multiple techniques and created designs that included characteristics from both traditional and modern schools. Thus, the couple attempted to incorporate multiple ideas and create projects that were distinctly different from the tendencies seen in the time period. The movement towards using materials such as metal and glass, while coming later to Australia than to the UK and the US, still found its place in the country. However, the Griffins explored other elements and forms, uniting more modern forms with rough stone and intricate ornaments. It can be assumed that the architects’ approach was a way of defying the cultural norm of using only one set of rules for creating a design – a standard for following one style. Instead, the Griffins mixed and matched the old and the new, creating different and easily distinguishable projects.

Kevin Borland

The works of Kevin Borland, an Australian architect who had been working from the 1950s to the end of the twentieth century, also show the difference between mainstream architecture and a unique vision. Borland started working after World War II, expressing interest in the global modernist movement. This can be seen in the architect’s early works, including the Olympic Swimming Stadium built before the Olympics in Melbourne (Figure 3). This project was completed in collaboration with multiple architects: Bill Irwin, Peter McIntyre and John and Phyllis Murphy. However, this group fell apart later as most architects found themselves interested in different styles. While working with these people, Borland followed the common rules of contemporary modernism.

Although Borland was interested in experimentation, the architect did not engage in a very distinct stylisation that would set him apart from other modernists. It can be observed in his early works for private property and houses. These examples show only a small part of his later tendencies as the residences have some details that set them apart from the conventional design. For example, coloured glass window parts and informal design of interiors can be taken into accounts as early signs of Borland developing a different style. Later, Borland continued to focus on residences but started to change some aspects of his designs. Although the architect’s next projects still were developed with many similarities to the accepted mainstream tendencies, Borland began adding innovative details to them. In the following years, the creator’s style has started to change even more as his political interests also shifted towards socialist ideas.

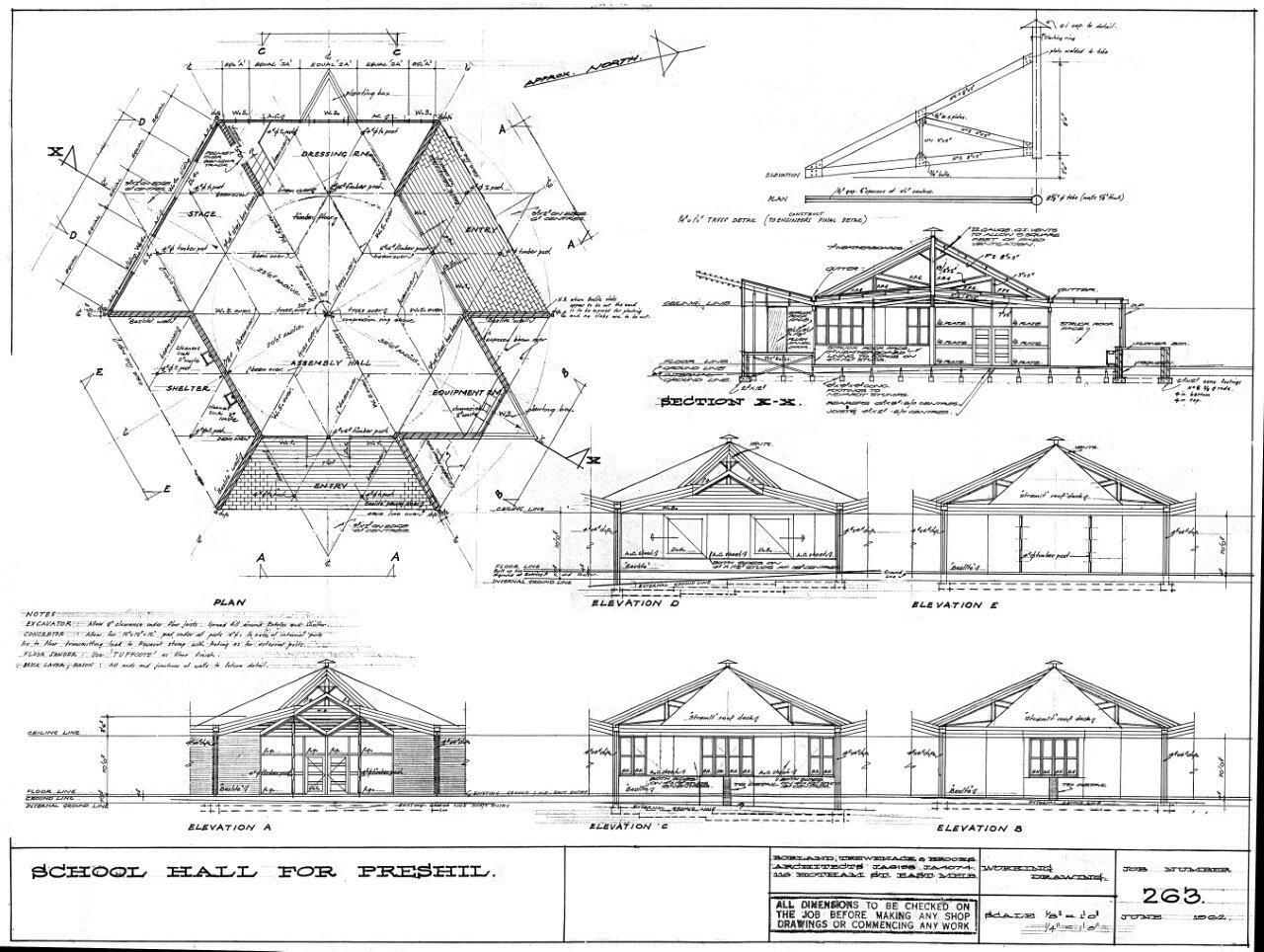

For example, in 1962, Borland was asked to design the Preshil school hall – an institution that was attended by his close friends. The space created by Borland differed from his earlier projects as it was less conventional and more experimental in nature. Interestingly, the halls’ symmetrical design was a result of collaborative work with the students who were allowed and encouraged to voice their opinions about the future construction. In the end, the architect built a symmetrical hexagonal space with a trussed roof that did not need columns, thus, giving the students more space and light from clerestory windows (Figure 4). The use of a different structure and light materials made the area appear less constrained and contributed to the communal views of the architect and the school’s attendants.

Starting from this project, Borland began to incorporate more robust and rough detailing into his other creations. Although the architect continued working on residences, his designs were significantly different from his previous commissions. However, some of his most interesting works were also connected to educational organisations which could be explained by his political interests and connections. Here, one can investigate the development of the Clyde Cameron College which is now occupied by the Murray Valley Private Hospital. This project was initiated and finished in the span of two years from 1976 to 1977 and was intended to be a space for the Trade Union Training Authority (TUTA) meetings and training.

The organisation closed in 1996, but the building remained one of the significant projects of Borland and his design team. In this example, the developed vision of the architect can be seen fully. The structure was created in the Brutalist style characterised by the use of rough materials, especially concrete, exposed details of the construction and lack of visible comfortability (Figure 5). This style has descended from modernism.

Following the rules of Brutalism, the Clyde Cameron College was designed with the exposed steel frame and concrete details, block formations, open-air handling, and painted service ducts. However, while the conventional view of brutalism was defined by modular elements and block structures, the design of the College guided by Borland had a few unique details that still fit in with the late Brutalist style. For instance, the building was full of spacious passages that resembled concrete pipes. These corridors connected some parts of the structure, breaking up its block design. The use of these forms added more memorable details to the building and made it one of the staples of late brutalism. In his career, Borland’s style progressively shifted from conventional modernism to brutalism with his use of materials and structural experiments. Thus, his decisions significantly affected the state of Australian architecture of the twentieth century, bringing more diversity to the designs of both private residences and political and educational entities.

Edmond and Corrigan

The Australian firm ‘Edmond and Corrigan’ was founded by Maggie Edmond and Peter Corrigan in the 1970s. These architects were interested in examining the cultural identity of the country and the lives of suburban areas. As Australia is an urbanised country, the architects’ interest was always directed at inner-urban constructions and styles. Edmond and Corrigan, on the other hand, explored the different influences of suburban life and culture on buildings, combining colours and textures removed from the everyday city life. As a contrast to other architects, Edmond and Corrigan explicitly stated that their firm is interested in finding Australia’s unique architectural style and voice that differs from conventional techniques influenced by the West. Moreover, Peter Corrigan’s experience in working with theatre sets and costumes could also possibly be considered a source of influence on the group’s projects.

While the architects created a number of highly distinctive and unique works, one of the most notable projects is the part of the RMIT University, the RMIT Building 8. This project was completed in 1993. It is one of the examples of postmodernism, although, according to the architects, it was also heavily influenced by the local culture. The building’s facade was created from brightly coloured stones; it features exposed pipes and construction details as well as items of various shapes (Figure 6). It also has polychromatic windows that decorate both front and back facades.

The interior is less structured as well, having a more complex layout. Multiple rooms have higher ceilings than others, some of them spanning several floors. The overall interior structure is rather chaotic which is consistent with the postmodern style and the firm’s other projects. Notably, the interior and exterior are both vibrant and full of details and shapes. The lighting in the lobby, for example, repeats the hexagonal shape used in the layout (Figure 7).

The facade’s design choices made by the architects were not accidental. The building represents elements from Melbourne’s history and depicts its cultural heritage. Thus, it is often called the ‘city in a building’ noting its description of the city’s life. For instance, the golden frames of the windows are reminiscent of older campuses and their gothic style. This search for identity is displayed in the architects’ own words. According to Corrigan, the political influence is always visible in architecture. Thus, the decisions made by the designers are an explicit representation of their political and ideological rebellion against the accepted norms of architecture – the rules and guidelines expressed by styles and schools. The architect also notes that expression in projects may be more important than refinement.

This example of architectural change influenced by local culture reveals the interest of the architectures in Melbourne’s cultural identity. It also can be interpreted as the answer to the rising trend of building skyscrapers that came with the introduction of modern office buildings to the cities of Australia. While their construction was not stopped, the city gained many designs that vary significantly both in their exterior and interior. The use of glass, metal and monochromatic colours was replaced by colourful stones and gold-rimmed windows. The range of bright colours incorporated into the architects’ designs also sets their buildings apart from others. These choices express emotions and personal attitude towards existing architecture of the city, creating a contrast necessary to show the pluralism of Australia as a whole.

Conclusion

The examples of buildings and designs described above are all examples of architects choosing to pursue their own ideology as opposed to following general trends and movements. The works of the Griffins were characterised by the desire to complement nature and create projects that combine old and new rules, resulting in works that defied the guidelines of one set style. Their contribution to the city’s architecture is still present in a number of projects, although many of the buildings were destroyed. Nevertheless, some buildings continue to show their mix of contemporary ideas and classic movements.

The works of Borland reveal a progression from the conventional to the Brutish, changing the alignment from following a particular school of thought to incorporating knowledge and experience into creating more powerful pieces. While Borland’s work may be seen as an example of Brutalism that follows guidelines of the style, the architect was able to introduce materials and forms unique to his personal vision. As a result, the combination of rough natural materials and exposed concrete brought a new accent to the city’s architecture and revolted against clear and safe modernism popular at that time.

Finally, the designs of Edmond and Corrigan are a clear representation of the author’s fatigue with the conventional modernism full of inexpressive and mainstream ideas. Instead, the architects attempt to include colours and textures that differ significantly from the most used ones, presenting a vision of a new and improved design that incorporates the city’s history at the same time. The expressionism of their models is visible in the political message that these projects send – the value of monochromatic buildings with a simple layout has no emotional and cultural importance to Australia and Melbourne. Thus, such constructions have no benefit and cannot represent the voice of the city or its history. On the other hand, the buildings that are less conventional and more expressive possess unique national traits and express the cultural pluralism of Melbourne and Australia as a whole.

Bibliography

“Building 8.” RMIT University. Web.

Corrigan, Peter. “Sunshine on the Valiant.” Lecture, Storey Hall, RMIT, Melbourne, August 29, 2003.

Evans, Doug, Huan Chen Borland, and Conrad Hamann, eds. Kevin Borland: Architecture from the Heart. Melbourne: RMIT University Press, 2006.

“Former Clyde Cameron College.”Victorian Heritage Database. Web.

Freestone, Robert. Urban Nation: Australia’s Planning Heritage. Collingwood: Csiro Publishing, 2010.

Hyde, Rory. “The Oeuvre of Edmond and Corrigan.” ArticetrureAU. Web.

Johnson, Donald Leslie. Australian Architecture 1901-51: Sources of Modernism. Sydney: Sydney University Press, 2002.

van Schaik, Leon. “Differentiation in Vital Practice: An Analysis Using RMIT University of Technology and Design Interfaces With Architects.” Architectural Design 83, no. 1 (2013): 106-113.

Vernon, Christopher. “Canberra: Where Landscape is Pre-eminent.” In Planning Twentieth Century Capital Cities, edited by David L. A. Gordon, 130-150. New York: Routledge, 2006.

Watson, Anne, ed. Beyond Architecture: Marion Mahony and Walter Burley Griffin: America, Australia, India. Haymarket: Powerhouse Publishing, 1998.