Executive Summary

Many children in New Jersey are still uninsured, although a third of all insured youth is covered by federal programs, Medicaid, and CHIP. This policy proposal outlines steps to expand coverage to create a system in which all children have access to high-quality, affordable medical services. At the moment, New Jersey’s health insurance presents barriers to low- and middle-income families, especially among minorities and immigrants. The idea of creating universal health coverage for children presents financial benefits for families and the government since it positively affects people’s health, academic performance, future health problems, and job opportunities. The policy brief outlines several recommendations on how to proceed with the expansion.

Introduction

Healthcare quality is a factor that impacts people’s lives and capabilities. One’s access to medical services is as crucial as the providers’ performance. Thus, it is essential to consider how local, state, and federal governments can make healthcare not only affordable but accessible to people with low income and highly limited funds (Kreider et al., 2016). Currently, the State of New Jersey, along with several other regions, participates in the Child Health Insurance Program (CHIP) (Larson, Cull, Racine, & Olson, 2016). Under this program and Medicaid, almost a third of all children in New Jersey are insured (Spencer et al., 2018). These initiatives decreased the rate of uninsured youth significantly, opening doors to other ideas such as universal coverage.

It is clear that health insurance is a way of accessing medical services for many Americans, including children. Nonetheless, affordable healthcare also has long-term benefits for young people. Children with Medicaid coverage, in comparison to those who are uninsured, perform better academically, skip fewer school days, and are more likely to finish high school (Brown, Kowalski, & Lurie, 2015; Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, 2017). Some of these consequences are long lasting – insured individuals have a higher chance of attending college, graduating, having fewer health-related problems and hospitalization, and earning more at their jobs (Wagnerman, Chester, & Alker, 2017; Wherry & Miller, 2016). Based on this data, is it appropriate to believe that the expansion of health coverage for children – the main proposal of this policy – will further contribute to the improvement of children’s quality of life.

Approaches and Results

To understand the potential of universal health coverage for children, one can consider the current progress in the state. According to the recent statistics, 19 states have higher rates of insured children, although not all of these areas are wealthier than New Jersey (Castro, 2019). The first potential issue is the federal policies on immigration. Strict anti-immigration policies discourage families from enrolling, even if they are legal citizens of the United States (Kreider et al., 2016). It is also possible that newly arriving residents are not aware of the possibility to insure their children under CHIP or Medicaid. The major part of information dissemination processes is performed in schools that may not address immigrant populations.

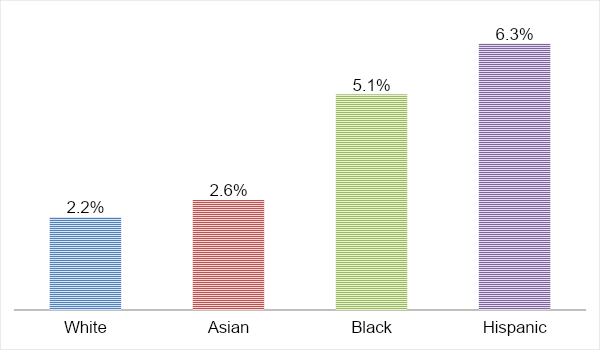

Another arising concern is health disparity among different population groups. As can be seen in Figure 1, uninsurance rates in the state indicate that Asian, Black, and Hispanic children lack coverage. Therefore, one may conclude that children of color remain at risk of inaccessible healthcare. One’s economic prosperity also plays a role in healthcare affordability. Children living under the federal poverty level and in middle-income families represent a large portion of the uninsured population (Boudreaux, Golberstein, & McAlpine, 2016). In the first case, some families cannot afford the premiums of the program, while children from families with a somewhat higher income are denied coverage.

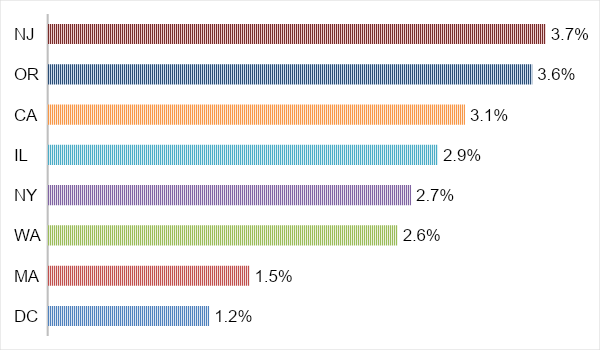

At present, New Jersey is among the only two states in the US that require children to wait for 90 days without insurance before enrolling into a government program (Castro, 2019). This gap presents an issue for many children whose conditions, acute or chronic, require a quick medical response. Many states have eliminated a waiting period, thus solving this problem and ensuring continuous health coverage. The next potential flaw in the current program is its lack of attention to the needs of immigrant children. Undocumented immigrants face similar health risks as citizens, and children, in many cases, are not responsible for the decision to relocate. To compare, several states that cover undocumented children have lower rates of uninsurance than New Jersey, as seen in Figure 2.

Implications and Recommendations

The benefits of universal health coverage presented above indicate that children’s lives can be influenced by affordable care significantly. Apart from that, the country and the state may see some positive effects as well. Thus, the main recommendation is to work towards expanding health coverage for children in New Jersey. The steps to implement this new policy include:

- Addressing statewide obstacles to universal coverage. The elimination of a waiting period could incentivize more families to apply to the program since their children will not be at risk of being uninsured for an extended period. Moreover, New Jersey can completely dismiss premiums for families under the poverty level. These changes will decrease the collection of funds, but the federal fund and administrative savings should cover it (Murphy & Oliver, 2019).

- Increasing awareness about the program. People from communities that are not contacted through school-based projects need to know about their opportunities. To connect with minorities, immigrants, and other vulnerable groups, the state can partner with local organizations and faith-based community leaders. Furthermore, additional funding should be allocated to public demonstrations and mentoring programs for parents (Flores et al., 2018).

- Covering currently ineligible children. If families whose income exceeds the poverty level cannot afford medical insurance, their children should be approved for CHIP or Medicaid coverage. Immigration status should also be discarded as an exclusion criterion for health coverage. Children gaining access to healthcare in these new settings should be protected by rigid confidentially standards.

Conclusion

The health of individuals depends not only on the quality of medical services but also on their accessibility. In New Jersey, there exists a potential of reaching full health coverage for children. The benefits of this prospect outweigh the risks, and the policy of affordable healthcare for all children leads to short-term and long-term changes for children and adults. The recommendations for this policy address existing disparities, such as the access to services of minority communities, undocumented immigrants, and currently ineligible children. The issue of confidentiality is also important to acknowledge to protect children’s private information.

Chosen Official

The chosen official for this policy is Louis D. Greenwald, the Majority Leader for District 6 in the state of New Jersey. The assemblyperson’s affiliation is Democratic, and he supported and sponsored many bills related to the expansion of healthcare for children (New Jersey Legislature, 2018). While his exact stance on the present policy issue is not available, his other endorsements indicate that he could agree with the recommendations. One can contact him through email, using the form on the official website of the New Jersey legislature.

Dear Representative Greenwald,

As one of your constituents, I am writing to ask you to review a policy proposal of Universal Health Coverage for Children. This policy has the potential of increasing the rate of insured children in New Jersey and eliminating health disparities for vulnerable communities. Research shows that access to healthcare leads to children having better academic performance, future health, and job perspectives.

I look forward to hearing from you.

Sincerely,

[Name]____________________________________

[Address]___________________________________

References

Boudreaux, M. H., Golberstein, E., & McAlpine, D. D. (2016). The long-term impacts of Medicaid exposure in early childhood: Evidence from the program’s origin. Journal of Health Economics, 45, 161-175.

Brown, D. W., Kowalski, A. E., & Lurie, I. Z. (2015). Medicaid as an investment in children: What is the long-term impact on tax receipts? Cowles Foundation Discussion Paper, 1979.

Castro, R. J. (2019). It’s time for all kids health coverage. Web.

Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. (2017). Medicaid works in New Jersey. Web.

Flores, G., Lin, H., Walker, C., Lee, M., Currie, J., Allgeyer, R.,… Massey, K. (2018). Parent mentoring program increases coverage rates for uninsured Latino children. Health Affairs, 37(3), 403-412.

Kreider, A. R., French, B., Aysola, J., Saloner, B., Noonan, K. G., & Rubin, D. M. (2016). Quality of health insurance coverage and access to care for children in low-income families. JAMA Pediatrics, 170(1), 43-51.

Larson, K., Cull, W. L., Racine, A. D., & Olson, L. M. (2016). Trends in access to health care services for US children: 2000–2014. Pediatrics, 138(6), e20162176.

Murphy, P. D., & Oliver, S. Y. (2019). FY2020 State of New Jersey budget in brief: Building a stronger and fairer New Jersey. Web.

New Jersey Legislature. (2018). Louis D. Greenwald (D). Web.

Spencer, D. L., McManus, M., Call, K. T., Turner, J., Harwood, C., White, P., & Alarcon, G. (2018). Health care coverage and access among children, adolescents, and young adults, 2010–2016: Implications for future health reforms. Journal of Adolescent Health, 62(6), 667-673.

Wagnerman, K., Chester, A., & Alker, J. (2017). Medicaid is a smart investment in children. Mortality, 6(7), 8-9.

Wherry, L. R., & Miller, S. (2016). Early coverage, access, utilization, and health effects of the Affordable Care Act Medicaid expansions: A quasi-experimental study. Annals of Internal Medicine, 164(12), 795-803.