Evolution of the African Region over the Past Century and Establishing of Cultural-Geographical Patterns

Long before the European invasion Africa had been organized into states that formed wider economic realms typified by trading activities among different states. Basically, one of the most economically productive realms was the West Africa who majorly traded with the north. To this effect, trading centers blossomed into thriving cities at the interior. Towards the south the cultural groups were readjusting while jostling one another while in the eastern coast of the Indian Ocean Arabian dhows were a common scenario. Batter trade was the most common means of trading.

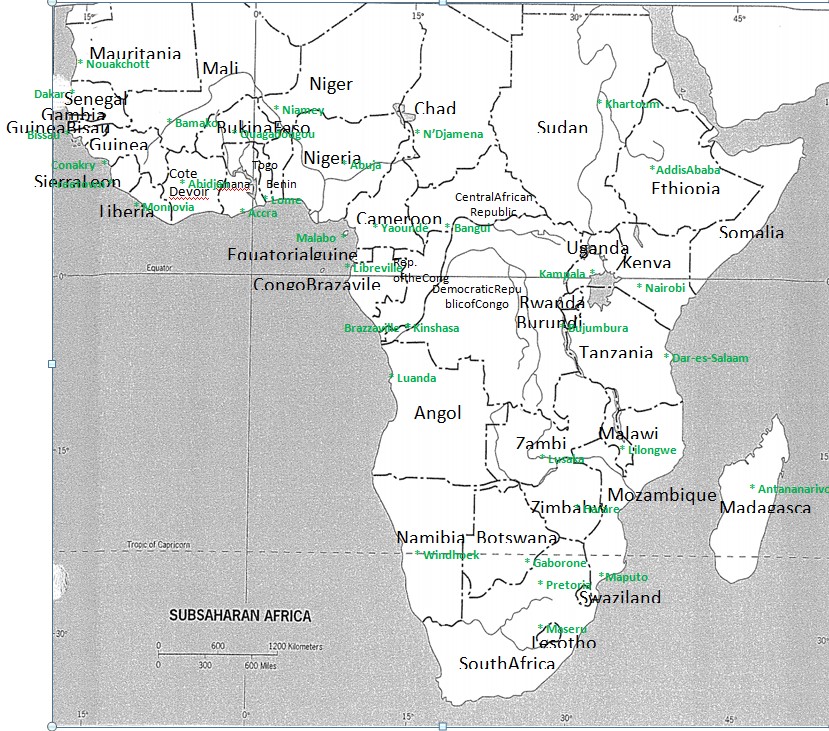

The Arabs on the eastern coast received slaves in exchange for gold and copper. As mentioned before these regions developed into city centers with Timbuktu and Kano exemplifying some of the ancient cities. Moreover, several states were formed including ancient Ghana which encompassed the current states of Mali and Mauritania. This particular one was well organized with routine tax collections and tolls on the imported goods a common place. In other places as well states and kingdoms rose. For instance, Ethiopian state and Buganda kingdom happened on the east (Kimble 320).

With European contact, came in slave trade that played a major role in disorienting African cultural settings. Primarily, the initial habitats of the whites were the coastal regions which later overshadowed the interior states’ developing pace. Consequently, coastal states such as Dahomey (currently Benin) owe their existence to slave trade. Reorientation of the trade also happened with the interior states steadily becoming depopulated thanks to white man’s insatiable quest for slaves.

As the Europeans started getting a foothold on the African continent, their political spheres of influence started overlapping prompting the stakeholders to carve out boundaries that would bring together cultural diversities into what are now the present states of Africa. Today, this has resulted in mixed fortunes with some states experiencing tribal wars e.g. Rwanda and Nigeria while others appreciate the need of cultural diversities e.g. Kenya with a host of 42 tribes but live peacefully.

Social Geography of the Caribbean and Northeastern South America as a Reflection of the Aftermath of the Atlantic Slave Trade

The trans-Atlantic slave trade took place on the Atlantic Ocean not later than 16th century ago. Chiefly, Africans were being transported from their native habitats to the outside world including the north and southern American realms to work as slave laborers in plantation farms. Vitally, the trade was oiled by the respective states’ kingpins who traded with Europeans for goodies in return for slaves. The West Africa was the most rampant spot for slave trade owing to its orientation close to the destination- America. As such, and with an overwhelming demand most West Africans found themselves either in the north or southern America (Schaefer 109).

The aftermath of trans-Atlantic slave trade is widely evident in the regions of the south Americas Caribbean and northeastern South American states. The south Americas Caribbean states include Venezuela, the Guianas and Colombia. A closer look at the population constituents in these states underscores the fact that these were the destinations of the slave laborers of African descent. As portrayed by the cultural fragmentation map, it is evident that the south Americas Caribbean states are categorized as tropical-plantation sphere epitomized by the dominant African culture that are largely dependent on agriculture. As such, adverse climatic conditions are an anticlimax to this region reducing people to abject poverty as is present (MacLeod and Jones 66).

Works Cited

Kimble, Hebert. “The Inadequacy of the Regional Concept” London Essays in Geography 2.17 (1951): 301-617. Print.

MacLeod, George, and Jones Mother. “Renewing The Geography of Regions.” Environment and Planning 16.9 (2001): 66-70. Print.

Schaefer, Frankline. “Exceptionalism in Geography: A Methodological Examination.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 43.3 (1953): 82-104. Print.