Introduction

Australia is one of the countries affected by the problem of sexual assault, as well as other forms of domestic violence. The studies conducted in various parts of the country show that the effect of sexual assault is adverse in the sense that it affects the victims in various ways. In the 2011-2012 crime victimisation survey, it was established that at least six million incidents were reported, and an estimated one million people were affected.

Past Trends

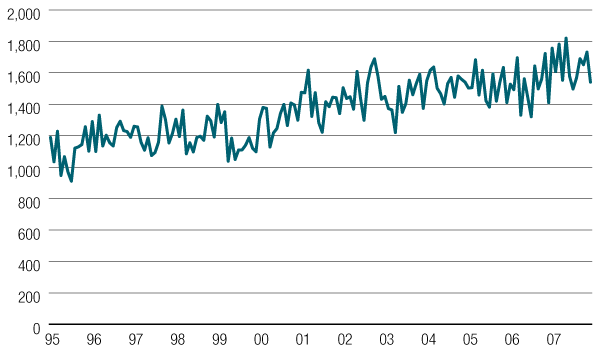

The worst affected regions as regards intimate partner violence in the country included New South Wales, Queensland, Victoria, and parts of Western Australia. In fact, over ninety-five per cent of cases took place in these regions. The trend shows that intimate partner sexual assault has been on the increase since 1995 since statistics suggest that it went up by fifty-one per cent. The following graph gives a summary of the intimate partner violence trend from 1995 to 2007 (Peter 2009, p. 1127). The graph plays a critical role in understanding the past trend of violence among intimate partners, especially in families.

The chart proves that intimate partner sexual assault in the country has ever been increasing because it went up to 2000 cases in 2007 from 200 in 1996. Analysts attribute this to the deteriorating ethical standards in society whereby individuals are simply concerned with satisfying their needs without necessarily considering the wishes, desires, and expectations of others. Many young couples in Australia are victims of intimate partner violence because they might have been raised by single parents.

As such, they fail to conceptualise the social norms and principles to an extent of trying to force everything. In the traditional society, it was rare to find married people complaining of intimate sexual abuse and assault because everything was done according to the set laws and principles (Plunkett, Shrimpton & Parkinson 2001, p. 264). However, the situation is different in contemporary society because the social fabric is absent and people do things without considering their consequences. Because of the soaring cases of sexual assault among intimate partners in the country, the government enacted the sexual offences act in 2003 to bring down the incidents. The law was expected to change people’s attitudes, as well as update other existing laws on sexual offences.

Current Trends

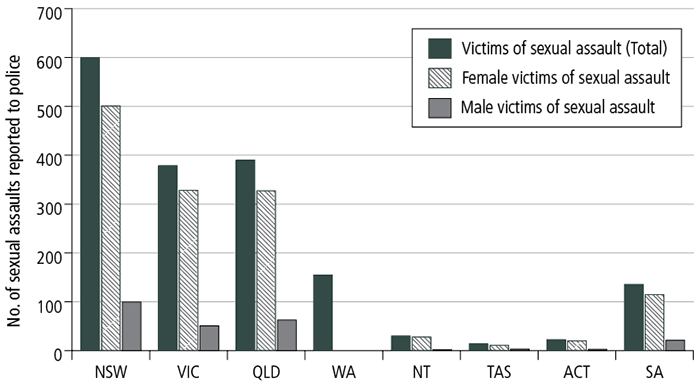

In the 2010-2011 survey, people were asked whether they had experienced any form of sexual assault in intimate relationships, especially in their marriages. Unfortunately, the results were shocking because 54000 Australians above the age of eighteen admitted to having been assaulted sexually. The study went ahead to ask the victims to give the features of the offenders (Owen 2008, p. 15). The study employed several methods in collecting people’s views on crime. The results indicated an increase in the rate of intimate partner violence, irrespective of the method used. The following table shows the current trend of cruelty among close partners in the country.

In each of the studies conducted, it is noted that intimate sexual assault is an ever present issue, with a majority of women being victims even though men are also assaulted in some places. The high prevalence of intimate sexual abuse, as well as other forms of domestic violence, is attributable to the changing nature of society whereby the family is no longer the primary socialising agent. The social dynamics, such as the emergence of the mass media, peer pressure, and insistence on individual freedom and rights are considered the major problems that facilitate intimate partner violence in the country (Putnam 2003, p. 269).

Unlike in the traditional society where the individual was expected to abide by the social norms, modernity presents something different because people have the choice of doing whatever they feel appropriate to their lives. For instance, parents no longer have control over their children, as the youth engage in heavy drinking and abuse of drugs, which in turn affect their decision-making processes.

Many victims of sexual assault report that their intimate partners are alcoholics or drug abusers, something that leads them to force them to do things out of their wish. The sexual offence law formulated in 2003 was meant to replace the previous enactment developed in 1956 concerning sexual abuse and domestic violence in general. Analysis shows that the law is preventing the occurrence of intimate sexual assault, but the trend is expected to remain the same because of other issues, such as failure to report the crime to the police and fear of stigmatisation.

Future Trend

Unless something is done urgently, the current trend is expected to remain because victims of domestic violence rarely report to the police as they fear retribution and stigmatisation, which is rampant in society. Since women are the main victims, they always believe reporting the issue to the law enforcement agencies will lead to automatic separation or divorce. The Australian society is already facing a serious challenge of handling single families and intimate partners, as well as those in stable relationships are reluctant to talk about the problem because they view sexual assault as an ordinary and minor problem that should not destabilise their unions (Salter 2003, p. 32).

In other words, society has come to accept and appreciate the challenge as a problem that cannot be eliminated because tyring to do so would lead to serious challenges, with divorce being the feared setback. In this regard, the number of those abused in intimate relationships is expected to remain the same or go up, because reporting rate is very low and government can do little to prevent the problem if perpetrators are not dealt with per the law.

The law formulated in 1956 was ineffective because it failed to explain the issue of consent sufficiently hence paving way for intimate partner sexual assault. It was always believed that a married couple had the right to access sex and any attempt to deny it was considered a social disorder. Therefore, many people saw it appropriate to apply force to satisfy their desires because they were entitled to them. However, the ideas and activities of feminists changed everything because women demanded equality in relationships and they were supposed to approve important decisions, such as sexual intercourse and the right time to have children.

Conclusion

The existing law is well placed to tackle all the problems facing sexual assault victims, but the problem lies with the population because few individuals are willing to report to the relevant authorities for proper action. Because of this, the situation is expected to remain the same unless the government formulates another law that will protect those willing to report.

List of References

Owen, K, Coates, H, Wickham, A, Jellet, J, Teuma, R & Noakes S 2008, Recidivism of Sex Offenders: Base rates for corrections Victoria Sex Offender Programs, Victoria Department of Justice, Melbourne.

Peter, T 2009, “Exploring tabbos: Comparing male and female- perpetrated child sexual abuse”, Journal of Interpersonal Violence, Vol. 24, no. 7, pp 1111-1128.

Plunkett, A, Shrimpton, S & Parkinson, P 2001, “A study of suicide risk following child sexual abuse”, Ambulatory Pediatrics, Vol. 1, no. 5, pp 262-266.

Putnam, FW 2003, “Ten-year research update review: child sexual abuse”, Journal of the American Academy of Child Adolescent Psychiatry, Vol. 42, no. 3, pp 269-278.

Salter, A 2003, Predictors: Paedophiles, rapists & other sex offenders: Who they are, how they operate, and how we can protect ourselves and our children, Basic Books, New York.