Abstract

Many players dominate the European oil and gas market. Although foreign companies participate in this market, most market players are local. Many oil companies intend to venture into this market as others plan to increase their market visibility. One such company is the State Oil Company of the Azerbaijan Republic (SOCAR). Based on the difficulty of increasing its market visibility in an industry that is dominated by many large players, this paper demonstrates that SOCAR can expand its operations in the European oil and gas market by adopting a four-tier marketing strategy which is based on Philip Kotler’s 4P’s of marketing. Concisely, in five chapters, this paper proposes that SOCAR should pursue joint ventures with existing oil giants in Europe by marketing itself as an oil distribution company (as opposed to an oil producer or explorer), price its products relatively lower than the competition and adopt personal selling techniques to increase its market visibility in the European oil and gas market.

Introduction

Statement of the Problem

Fossil fuel drives the wheels of modern economies. However, there are ongoing efforts to reduce the reliance on oil and gas through green energy efforts, which are concentrated on renewable sources of energy. Developing nations are at the forefront in increasing the demand of the world’s oil and gas energy, but developed nations have historically constituted the biggest market block for the same resources. Therefore, most of the world’s consumption of energy occurs in advanced economies such as Britain, theUnited States, China, and Japan (Amineh 2010). Europe and America are the biggest markets for oil and gas energy. Their high demand for energy stems from the robustness of their economies.

Like most competitive industries, many players compete for limited resources in the oil and energy market (Gammie 1997). Notably, many people know the countries that produce oil but not the constituent companies that exploit this natural resource. In Europe, some of the major oil companies include British Petroleum (B.P), Royal Dutch Shell Plc, Exxon Mobil Corporation, Wintershall Holding AG, Lundin Petroleum AB, A.P. Moller-Maersk A/S, Chevron Corporation (among others) (Wood 2011, p. 2). These companies are only some of the major players operating in the European oil and energy market because there are many other companies that are struggling to increase their market presence in the same market.

With today’s increasingly growing trend of globalisation, many foreign oil companies are willing to enter the European oil market. The liberalisation of the European market and the subsequent formation of the European Union (E.U) have further catalysed the penetration of such companies in the European market (Harbo 2008). However, most companies, which have dared to venture into the European oil market, have found stiff competition from other existing companies (more so, local oil companies that have historically dominated the market) (Osborn, 2005). Moreover, intense politicking (informed by ongoing policy formulations within the European Union and existing international conflicts with some of EU’s neighbours such as Russia) characterises the European oil and energy market (Heinberg, 2005).

However, the ongoing political forces within the market are incomparable to the stiff competition realised by most foreign companies willing to venture into the European oil and energy market. Some companies, which have successfully managed to penetrate the market, have only done so substantially while others have failed to secure a continental presence in the competitive market. For example, numerous works of literature document the unsuccessful penetration of foreign oil companies in Europe (Amineh 2010). Still, the rush to dominate the European oil and energy sector is strong, and many companies are striving to outdo one another to increase their market shares.

It is crucial to highlight that the main challenge witnessed by foreign companies intending to venture into the European oil and energy market is the fact that Europe is also a producer of oil and energy. Therefore, unlike geographic regions, which do not produce oil or gas, Europe is a net producer of natural resources. Taiyou Research (2011) explains that “Europe is the world’s fourth-largest producer of oil and gas, with the North Sea basins containing the largest oil and gas reserves in Europe” (p. 1).

Dominant market players in the European oil and gas sector hail from Norway, Germany, Italy, the UK, Romania, France, Ukraine, Netherlands, Spain, Hungary, Finland, Greece, Lithuania, Sweden, Portugal, Slovakia (among others) (Taiyou Research 2011). Some of these countries are dominant producers and distributors of oil products, while others only produce for their domestic consumption. In addition, some of the countries mentioned above have been dominant players in the world’s oil and energy market for a long time, and similarly, they are home to some of the biggest oil companies in the world. For example, Europe’s British Petroleum (BP) and Royal Dutch/Shell have been dominant players in the world oil and energy market. The presence of such dominant multinationals makes it even more difficult for foreign oil companies to venture into the European market.

However, the European market is very big, and even though there are some dominant oil producers in the continent, they are not able to meet (sufficiently) the rising demand for oil and gas energy in Europe (Taiyou Research, 2011). This situation has led to the growing bill of oil imports and the emergence of new opportunities for foreign companies to venture into the same market. It is through this opportunity that this paper seeks to explore the alternatives for the State Oil Company of the Azerbaijan Republic (SOCAR) to increase its market presence in the European market.

Purpose of the Study

Venturing into new markets can be a brain-raking process for companies. Taiyou Research (2011) explains that “Many companies that have succeeded locally find it difficult to venture into new business markets, especially if it is somewhere across the globe. Few business owners have the nerve to research and risk their investments in new markets or send their workers to initiate a production unit in another part of the world, yet this is the pinnacle of business growth” (p. 3).

The hesitation by some companies to venture into a new market is understandable because global market expansions pose great risks. However, it is also important to point out that successful market expansions have a high return. Venturing into a new market is especially not for those weak at heart because it may defy a company’s corporate philosophy, business practices and other aspects of core corporate governance as investments continue to flow into the new markets. Such investments may be worth millions of Euros. In fact, in more capital-intensive industries like the oil sector, such investments may run into billions of Euros. Unfortunately, no matter how much an organisation may be prepared for such intensive undertakings, the risk of failure exists. Indeed, companies may be bankrupt if they unsuccessfully expand into new markets (Osborn, 2005).

Since such risks exist, scholars, professionals, economists, and academicians have developed numerous international business strategies. The outcome of their involvement is the availability of several strategic options. Some of these strategies are very specific, and therefore, not all companies can adopt them. It is therefore perplexing for managers to venture into new markets because they have several alternatives that may, or may not succeed. Notably, the nature of a company’s operations and the characteristics of the host markets play an integral role in the determination of the right marketing strategy to adopt in new markets. This paper focuses on the oil and energy market in Europe and the market dynamics of the same industry, determines the right strategy for SOCAR to venture into this market. Competition is at the centre of this analysis because any new (or foreign) company intending to venture or expand its market operations in the European oil and energy sector needs to be aware of the existing presence of other dominant players in the industry. Moreover, prospective market participants need to understand that the energy industry is largely oligopolistic (Talus, 2011). Purposefully, this paper seeks to establish the right marketing strategy for SOCAR as it tries to increase its market presence in the European market. The following research objectives define this aim:

- To establish which marketing strategies are most beneficial for SOCAR as it expands its market presence in the European oil and energy market.

- To investigate which business sector SOCAR needs to concentrate on as it expands further into the European oil and energy market.

- To find out which resources SOCAR needs to use to achieve success in the European market and why these resources are crucial to SOCAR’S marketing strategy.

- To establish the challenges of expanding SOCAR’s operations in the European oil and energy market.

- To demonstrate how SOCAR can use its marketing strategies to circumnavigate the pitfalls of the European oil and gas market.

Importance of the Study

The importance of this study can be broken down into two components. First, the findings of this study will be important for energy companies that are willing to expand their operations in the market. With keen consideration of the industry and company dynamics surrounding the marketing initiative, this paper provides a guideline for strategy formulation. Secondly, by highlighting the nature of the European oil and energy market (and how foreign companies can overcome existing barriers), the outcome of this paper also contributes to the existing body of knowledge regarding international market ventures. More importantly, this study provides an up-to-date understanding of successful business practices in the European oil sector and how foreign companies may use such practices to improve their visibility in the European market. This analysis provides a framework for future studies, as well.

Literature Review

SOCAR’S Activities and Global Presence

Since its inception, the State Oil Company of Azerbaijan Republic (SOCAR) has undertaken major oil concessions in Azerbaijan (involving the production, sale, and distribution of oil products) (SOCAR 2012). The extensive outreach of the company’s operations ranks it among the biggest oil companies in the world. Indeed, recent corporate rankings reported SOCAR as the 68th biggest company in the world (with a total asset base of $20 billion) (Ibrahimov 2007, p. 1). SOCAR’s activities are diverse as they range from exploration, preparation, distribution, and exploitation of oil fields in not only Azerbaijan but also other countries around the world. Some of its auxiliary activities include the transportation, processing, and distribution of oil and gas products. To sample the company’s production capacity, Ibrahimov (2007) explains, “In 2006, SOCAR produced from offshore and onshore fields about 7.84 million tons of oil and 4.34 billion cubic meters of gas” (p. 3). About 61,000 specialised employees run the company’s operations.

SOCAR’s operations stretch far beyond its host market (Azerbaijan) into other markets around the world, such as London, Vienna, Geneva, Frankfurt and other cities around the world (SOCAR 2012). Mostly, SOCAR has a representative office in these locations, with its activities ranging from international oil consortiums to franchises and partnerships around the globe. In Europe, SOCAR Trading SA is primarily involved in the market and distribution of the company’s products, but its operations and activities have not been very visible.

Previous International Marketing Approaches Adopted by SOCAR

Like other multinational companies operating in the global market, SOCAR’s international marketing strategy has been very calculated. In other parts of the world (Non-European markets), SOCAR has been able to develop successful joint ventures with local companies. Such is the case in Turkey and Georgia (Ibrahimov 2007). In Europe, several marketing strategies complement the company’s presence in the market. Recently, SOCAR purchased a subsidiary company of Exxon Mobil (Esso) to increase its market presence in Europe (Auty 2006). Through successful consortiums and the support of its subsidiary companies, SOCAR has also been able to entrench its presence in the European market (notably Switzerland).

However, in some of the company’s market, SOCAR has been independently carrying out its operations. Mostly, the company’s operations in Azerbaijan have been independently undertaken, but some of its offshore operations occur with the help of other companies. SOCAR’s experience in the oil and gas market stretches more than a decade ago when the company was engaged in the exploitation and exploration of oil in Russia. Its wider acceptance as the main oil exploration company in the South Caucus region also complemented its oil exploration activities in Russia (Ismailzade 2006, p. 26). Throughout the soviet times, SOCAR was able to develop a pool of specialised oil exploration experts who have been instrumental in undertaking oil exploration ventures across the globe.

SOCAR’s proficiency and experience in venturing into international oil markets trace to Azerbaijan’s post-colonial period. The company’s first venture in the international market was through its subsidiary company Azretrol that ventured into Moldova in the Soviet period. Since then, the company has been able to entrench itself in other parts of the world. Notably, its activities around the Caspian Sea form a major part of the company’s oil exploration history because it has been able to assist countries around the Caspian Sea (such as Georgia) in exploring and exploiting their oil. Its activities in Africa and Asia also form a significant part of the company’s international operations. Slowly, foreign oil explorations in virgin oil fields of Asia and Africa are forming a huge percentage of the company’s operations (Ismailzade 2006).

Nonetheless, SOCAR’S venture into Georgia was only natural because the country is geographically close to Azerbaijan. Over the years, the construction of more refineries made SOCAR a strategic partner in the sale and distribution of oil and gas products in Georgia. By building more refineries, SOCAR has been willing to increase its presence around the black sea. This strategy is part of a larger ploy to export more oil to black sea countries because the current transportation of oil through the existing terminal is only about ten million tones and the company intends to double this capacity to about 20 million tons of oil (Ibrahimov 2007). Besides the ambition to increase its presence in Georgia and the surrounding states, SOCAR plans to establish SOCAR-Georgia Company, to establish new petrol stations around Georgia (as part of the company’s plan to increase its market visibility in the Caspian Sea).

SOCAR also harbours other ambitious plans to expand its operations in some of its international markets such as Turkey. This plan complements SOCAR’s willingness to establish a monopoly in the country (International Business Publications 2008). In 2011, it was reported that “In early December R. Abdullayev and chairman of the Turkish oil company Turcas Erdal Aksoy signed a protocol with SOCAR to establish a joint company” (Ibrahimov 2007, p. 10). In a press statement from SOCAR’s president, SOCAR acknowledged that it intended to sell oil and gas products in Turkey because of its strategic geopolitical position with Turkey (International Business Publications 2008). Most of the oil products exported in this agreement originate from Azerbaijan and by developing a new oil distribution system through Turkey; SOCAR intends to penetrate other markets in the European peninsular. Through the Turkey deal, SOCAR aims to open more opportunities for trade with the rest of Europe by bringing some of its core partners such as Ukraine and the Republic of Moldova into the deal. Other countries expected to benefit from this expansion includes some black sea states such as Romania, Bulgaria, and other countries (Oxford Business Group 2009).

Comprehensively, SOCAR has recognised the need to expand its operations from traditional markets to non-traditional markets. It is through this realisation that the company introduced SOCAR Trading (based in Geneva) (SOCAR Trading SA, 2012). This company is a subsidiary of SOCAR and acts as an international marketing agency for the company. So far, it has done a remarkable job marketing the bulk of SOCAR’S crude oil exports not only in Europe but to other parts of the world as well. Some of the crude oil marketed through this subsidiary has not originated from Azerbaijan because the subsidiary also trades third-party crude oil. In fact, SOCAR Trading SA (2012) explains that third-party business constitutes about a third of all SOCAR Trading operations.

SOCAR trading has also been able to assist its parent company in making investment decisions in overseas markets through logistical support. Concerning this support, SOCAR Trading SA (2012) explains that “Since it shipped its first cargo in April 2008, SOCAR Trading has successfully optimised and diversified the SOCAR barrel among end-users across Europe, Asia and America” (p. 3). SOCAR Trading has also been successful in leveraging its system barrels for third party business through logistical support and the formulation of the right strategies in oil logistics. Recently, SOCAR Trading expanded its operations into other countries and cities such as “Baku, Singapore, Vietnam, Dubai, and Lagos, with New York, Cairo, and Istanbul to follow” (SOCAR Trading SA 2012, p. 4). Nonetheless, SOCAR’s European success largely depends on its ability to circumnavigate market challenges and opportunities. Through an exploration of the nature of the European oil and energy market, this paper highlights these challenges and opportunities below.

European Oil and Energy Market

Large concentrations of the European oil and energy markets are in the northern part of the continent because countries bordering the North have the highest concentration of oil and natural gas resources (Key Note Limited 2007). Among the countries known to produce the highest volumes of crude oil products are U.K, Denmark, Italy, Romania, and Germany. These countries produce the highest volumes of crude oil in that order (Osborn 2005). In addition, the Netherlands produces high concentrations of natural gas. Germany, Italy, Romania, and Denmark (in that order) second its production (Osborn 2005). Interestingly, some of the above-mentioned countries have not been part of the EU for a long time. For example, Romania (a top producer of crude oil and natural gas), only joined the EU in 2007. Despite the participation of the EU countries in the production and distribution of oil, the domestic demand for oil in the EU surpasses its local production. Consequently, there is a strong need to supplement domestic demand by oil inputs.

Motivated by the fear of being heavily dependent on foreign oil, the EU is investing a lot of money to improve its oil infrastructure to make it easier to distribute the existing oil. Mostly, these investments work to improve the oil pipeline network and boost the EU’s oil storage capacity. The conflict between the EU and its neighbouring states is a strong influencing factor in the sale and distribution of this oil (because the EU is trying to avoid any cases of oil and gas disruptions if there is any disagreement with some of its neighbours). Regarding the sourcing and distribution of natural gas, the European Union is turning to its Arab allies to source oil. However, the conflict between Western powers and some Arab states has undermined this initiative (Ceric 2012). Therefore, Europe has only sought partnerships with friendly Arab nations. Already, North Africa and Qatar provide some of this oil. Europe is also building new liquefied natural gas (LNG) terminals to facilitate the distribution and storage of this commodity.

Since SOCAR engages in the exploitation and exploration of oil around the world, the ongoing decommissioning of oil ventures in the EU (especially around the North Sea) is a worrying trend. The decommissioning of these oil fields show that there is little potential to expand Europe’s oil production capacity (Ceric 2012). Notably, there has been a significant decline in the production of oil within the EU (as seen from the steady decline of oil production in the UK). In fact, recent and new discoveries of oil are usually of a small proportion, thereby making such projects economically unviable (Key Note Limited 2007). Experts say that until the price of oil significantly increases, the EU is an uneconomical region for oil exploration and exploitation. Currently, it would be very expensive to invest in oil production in Europe because the market does not provide adequate compensation for such investments, through high oil prices (Ceric 2012). Currently, many oil companies are looking for new geographic regions around the world to continue their oil and natural gas explorations. This trend is bound to work against SOCAR, especially in the exploration and exploitation of oil in the EU.

Apart from the numerous efforts aimed at improving the EU’s capacity to import and store oil and natural gas, it is important to acknowledge the growing attention that climate change concerns plague the EU. Mainly, climate change concerns are forcing major E.U consumers to find new ways of reducing their carbon footprint on the economy. This trend is part of a global push to reduce global carbon emissions through the adoption of green energy sources (Oxford Business Group, 2009). Already, airline companies in the EU are warming up to these prospects and seeking new ways of reducing their fuel consumption. Car manufacturing companies are also developing new prototypes that have low fuel emissions. This trend manifests in almost every sector of the EU economy as the region strives to embrace sustainable energy technologies.

Complementarily, the quest to reduce oil and gas consumption in the EU works alongside the push to develop more alternative sources of energy within the continent. For example, many scientists are seriously considering the prospects of developing nuclear power to supplement the existing alternative sources of power (Key Note Limited 2007). Other alternative energy sources such as wind power, solar power, biogas fuels, and other similar energy sources are also gaining prominence across the European continent. Undoubtedly, the adoption of such energy sources will have a negative impact on the existing oil and gas market. This trend works against prospects to launch new oil companies in the EU. Moreover, oil companies are increasingly gaining the reputation of being ‘money-hungry’ goons who would do anything to safeguard their interests. Such a reputation is likely to stick to new companies like SOCAR, which aim to increase their geographic visibility around the EU.

Theoretical Understanding

Absolute Advantage Theory

The absolute advantage theory explains why foreign companies should set up businesses in other countries (David 2010, p. 11). Adam Smith (the founder of the theory) explains that a company can realise business success in another country if it establishes its absolute advantage over the other country. For example, countries which have natural advantages like a better geographic location, cheap labour, fertile land, and mineral resources (like oil) have a strong business advantage over other companies that do not have these resources. For SOCAR, its endowment with huge reserves of oil and natural gas from its host nation, Azerbaijan, offers it immense business advantages over its European counterparts because the company guarantees a steady supply of the natural resource over a long period.

Similarly, the company may equally use its immense experience in oil exploration, production, exploitation, and distribution activities to gain a strong business advantage over its main competitors (David 2010). These advantages define its absolute advantages to use over its European competitors. An unrelated example of the adoption of the absolute advantage theory centres on the selective production of silk products from Indian factories. Here, India has an absolute advantage in the production of silk saris because of its skilled labour force. In SOCAR’s case, its competencies in the production, exploitation, exploration and distribution of oil and other energy sources define its absolute advantages in the European market. Nonetheless, the main weakness of the absolute advantage theory is that it gives no provision to countries that have no absolute advantage (at all). In the same regard, this theory does not give any provision to those countries that have all absolute advantages (this has been its main basis of criticism) (David 2010, p. 11).

Comparative Cost Theory

Another theory that has been beneficial in understanding SOCAR’s venture in the European oil and gas market is the comparative cost theory. The comparative cost theory developed as a follow-up to the absolute advantage theory. In some quarters, people know this theory as the Ricardian model (after its founder David Ricardo) (Wood 1993, p. 301).

“According to the comparative cost theory, two countries should do business with each other if one country is having an advantage in the ability of producing one good relative to another good as compared to some other country’s relative ability of producing same goods” (Gemini Geek 2011, p. 6).

Using the above explanation, we see that if the US can produce 25 bottles of wine and 50 pounds of beef while France can produce 150 bottles of wine and 60 pounds of beef (using the same resources), France has a comparative cost advantage over the US. Normally, it would be okay to see no business transacted between the two countries since it will be uneconomical to do so, but the comparative cost theory states otherwise. In essence, the comparative cost theory shows that France sacrifices two and a half bottles of wine to produce beef (this calculation is derived by dividing the number of bottles of wine and the weight of beef produced in France – 150/60) (Gemini Geek 2011). Similarly, to determine the number of wine bottles that the US sacrifices to produce beef, we divide the number of wine bottles that the US produces with the weight of beef it produces (25/50) (Gemini Geek 2011). Here, we see that the US sacrifices half of a bottle of wine to produce a pound of beef and therefore, in such a situation, we see that it is more expensive to produce a bottle of wine in France. The comparative cost theory would hereby suggest that France should import wine from the US, and similarly, the US should import beef from France (Wood 1993, p. 301). This strategy makes more economic sense.

Similarly, using the above model of ascertaining the comparative cost advantage, the comparative cost advantage theory also applies to SOCAR’s venture into the European oil and energy market. Its applicability stems from its position to provide a stable supply of oil and energy products in the European market. For example, compared to its competitors in the European market, it would be cheaper for European energy consumers to buy energy products from SOCAR because of the close proximity between major European markets and Azerbaijan. The comparative cost theory, therefore, dictates that it would be cheaper for Europe to buy oil from Azerbaijan as opposed to sourcing the commodity from far-flung areas like oil producing nations in the Far East, or in Africa (Wood 1993).

Therefore, after considering the distribution costs, and the geographical concerns of marketing and distributing oil throughout Europe, SOCAR would be in a better position than most of its competitors to supply Europe with oil and other energy products. Through the above explanation, the comparative cost theory highlights one key concept of marketing – place. Therefore, within SOCAR’s marketing strategy, the company should market itself as the most practical alternative for providing oil and energy products in Europe. Azerbaijan’s close proximity to Europe gives SOCAR this geographical advantage. Comprehensively, the comparative cost theory emphasises the importance of SOCAR to market itself as having a strategic position to supply and distribute oil in Europe.

One criticism of the comparative cost theory is the restrictive nature of the model. In other words, the comparative cost model only analyses international trade when only two countries are involved (or when there are two products involved). Since international trade normally involves more than two countries and two commodities, the comparative cost model fails to predict the outcome of such situations. This limitation directly applies to the understanding of SOCAR’s market venture in Europe because Europe is an expansive region, which is characterised by many countries and geopolitical zones. Moreover, SOCAR does not only engage in one product or service; its speciality stretches across several oil production and distribution services. Therefore, considering the dynamic nature of SOCAR’s operations and the multiple country demographics characterising Europe, it is somewhat difficult to predict SOCAR’s market strategy in Europe through the restrictive model of the comparative cost theory.

Opportunity Cost Theory

The opportunity cost theory of 1959 is also widely used to explain the intention of multinational companies to engage in international trade (Nicholson 2011). The opportunity cost theory bases its application on the determination of alternative cost values so that a company (or consumers) can determine which strategy is the most viable. Usually, the ascertainment of such a value concerns the ascertainment of forgone costs, while choosing a specific strategic plan. The opportunity cost theory focuses on forgone values while pursuing a specific alternative.

This theory is important to the understanding of SOCAR’s strategy in Europe because it critically analyses the efficiency of exporting oil and energy products from Azerbaijan to Europe. This theory closely links with the comparative cost theory because they both highlight the efficiencies realised when Europe supplements its oil consumption through SOCAR’s import products. The comparative cost theory stipulates that it would be cheaper for Europe to buy oil and energy products from SOCAR, while the opportunity cost theory stipulates that the same strategy would be more efficient. Therefore, SOCAR is in a better position to export its oil products from Azerbaijan to European markets because it would be cheaper and more efficient to do so.

Ordinarily, the opportunity cost theory would include the presence of another alternative option for Europe to meet its energy deficit (Nicholson 2011). However, for purposes of this study, this energy deficit includes the sourcing of energy products from other markets apart from Azerbaijan. By extension, this outsourcing should also include the supply of oil products from other companies besides SOCAR. Comprehensively, the opportunity cost theory dictates that Europe should pursue the cheapest and most efficient option for meeting its energy deficit. In the context of this study, SOCAR manifests as the cheaper and more efficient option for meeting Europe’s energy deficit.

After ascertaining SOCAR’s position as the cheapest option for meeting Europe’s energy deficit, the company’s marketing strategy should highlight this fact. Therefore, from SOCAR’s market strategy, European energy consumers should see SOCAR as the cheapest alternative for supplementing its energy needs. The opportunity cost theory would also show that other market participants would constitute expensive options for meeting Europe’s energy demand (Nicholson 2011). SOCAR’s relative cheapness (compared to other options of selling and distributing oil and energy products in Europe) highlights one ‘p’ (price) from Kotler’s four ‘Ps’ of marketing. Therefore, when formulating SOCAR’s market strategy, the company may market itself as the cheapest and most efficient option for supplementing Europe’s energy deficit. The forgone options form the opportunity cost.

Even though the opportunity cost theory informs SOCAR’s price strategy, the theory has been criticised for its failure to compare different opportunities across varying market dynamics. Moreover, as opposed to the one-track perspective of deriving economic benefits by forgoing one benefit, it is equally possible to derive multiple economic benefits, by forgoing more than one alternative. For example, if an economy is in its production possibility frontier, it is very easy to obtain economic benefits by forgoing multiple opportunity costs. Therefore, the opportunity cost theory only applies to microeconomic situations where individual utility gains are profound. This one feature informs the Keynesian macroeconomic model. Therefore, since some investment opportunities may provide the same gains as other types of investments, it is difficult to apply the opportunity cost theory in macroeconomic situations. These limitations highlight the weaknesses of the opportunity cost theory.

Vent-for-Surplus Theory

Mehmet (1999) explains that the vent-for-surplus theory outlines how unemployed economic factors complement global trade because countries do not have similar production capacities. Naturally, countries that have many surplus goods and services deem it economical to export such outputs so that they do not run the risk of experiencing losses from the waste or misuse of such outputs in their domestic economies. If this option remains unexplored, a specific section of the country’s economic factors will seize to operate. Conversely, such a situation would lead to the overall decline of the nation’s output. The main argument of the vent-for-surplus theory is the support of international trade to avoid economic wastages.

SOCAR’s export of oil from its primary market (Azerbaijan) highlights the tenets characterising the vent-for-surplus theory because Azerbaijan has an excess output of oil, which it should offload to the international market. In fact, according to Lerman (2010), Azerbaijan produces about 800,000 barrels of oil every day, and most of this production is more than enough to meet the country’s local demand. Azerbaijan’s economy practically stems from oil boom trade of the seventies and even with the expansion of oil fields in other countries around the globe; Azerbaijan remains a leading producer of oil (Lerman 2010). Without such a channel for selling its surplus produce, Azerbaijan would experience wastages and economic inefficiencies stemming from lower prices because of imbalances in demand and supply. Therefore, the vent for surplus theory provides a model for companies that intend to float their surplus produce in the market through the most efficient and profitable manner.

Therefore, international trade offers an opportunity for countries with surplus goods and services to ‘vent’ their economic surpluses in the international market, thereby enjoying the benefits of international trade (Mehmet 1999). Through this strategy, factors of production in the exporting country will be fully utilised, and the value of goods and services in the domestic economy would stay at sustainable levels. Similarly, it is crucial to point out that in such a situation, it is easy to exploit unemployed labour so that the economy operates more efficiently. Therefore, the vent-for-surplus theory justifies SOCAR’s push to penetrate into the European market because it is through this strategy that SOCAR can fully exploit its oil potential from Azerbaijan. In addition, through a market expansion into the European economy, there will be no wastages of oil or gas products from the Azerbaijan economy. Similarly, there will be no under-utilisation of specialised skills from SOCAR’s worker pool.

Comparative Advantage Theory

Since SOCAR expects to face stiff competition from other European oil companies, the importance of the comparative advantage theory surfaces. The comparative advantage theory complements the need to have a robust marketing plan for SOCAR as it tries to improve its visibility in the European oil and energy market. More importantly, the theory explains why SOCAR needs to re-invent itself in the European oil and gas market. The comparative advantage theory refers to a country’s ability to produce goods and services at relatively lower costs than its competitors do (Goel 2009). Usually, marginal and opportunity costs establish the level of comparative advantage that an organisation (or country) has over another. This theory largely explains the differences in international trade by demonstrating how different countries benefit from trade (even if one country produces a bulk of goods or services). Usually, the gains derived from such international transactions become the ‘gains of trade’ (Maneschi 1998).

The law of comparative advantage, which stipulates the importance of countries to sustain their comparative advantage by re-inventing themselves throughout different levels of operation, demonstrates the importance of the comparative advantage theory (Goel 2009). Particularly, this understanding closely refers to SOCAR’s activities on the international market because the company sustains its comparative advantage by re-inventing itself in the international market. This relationship explains the association between the comparative advantage theory and globalisation because globalisation also encourages companies to penetrate new markets through corporate rebranding. Analysts draw close similarities between globalisation and the comparative advantage theory because companies sustain their comparative advantages by re-inventing themselves on the global map (Goel 2009). Furthermore, experts draw a strong link between globalisation and the ability of globalisation to increase a company’s efficiency of operation.

After carefully scrutinising the structure and concepts of the comparative advantage theory, we see that the theory encourages companies to operate as if there were no international barriers to trade (Maneschi 1998). Conversely, if this theory applied to SOCAR’s intention to expand into the European oil and gas market, the comparative advantage theory would stipulate that SOCAR should expand without succumbing to the barriers of trade. Practically, it is difficult to defend this philosophy because there are substantial barriers to trade on the international market. For example, some countries still have protectionist policies that act as impediments for international trade. These impediments highlight the difficulties SOCAR faces as it ventures into the European energy market (the dominance of European oil companies pose a barrier to the entry of foreign companies).

Furthermore, different countries have different economic environments that pose varied dynamics in international trade. Some of these dynamics are unfavourable to international trade (Goel, 2009). Besides the challenges of having a complementary economic environment, critics of the comparative advantage theory say that even if the theory is effortlessly applied, so companies that have a stronger comparative advantage produce goods and services (instead of companies that do not share this advantage), the flow of capital is not going to be equitable (Maneschi 1998). This observation contradicts suggestions advanced by proponents of globalisation who show that international trade is a zero-sum game where everybody benefits equally. Equitable capital distribution only occurs in the perfect market, but perfect markets do not exist. This criticism forms part of the challenges informing SOCAR’s quest to succeed in the international market.

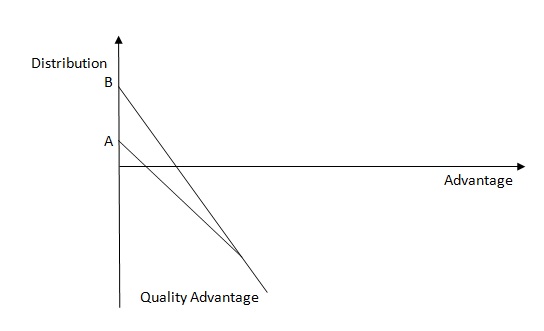

Assuming that SOCAR was represented by the letter ‘B’ and SOCAR’s main competitor was represented by the letter ‘A’, the above diagram shows that SOCAR has better distribution and quality advantage over its main competitor. However, SOCAR’s distribution advantage is greater than its quality advantage. Therefore, while formulating a marketing strategy to expand its operations in Europe, SOCAR should market its distribution advantage as the main selling point (as opposed to its quality advantage). This way, SOCAR would stand a better chance of achieving significant success in its European expansion. However, if it markets its quality advantage as its main selling point, SOCAR would receive more opposition from its main competitor (‘A’) because ‘A’ also has a relatively strong quality advantage. Conversely, if ‘A’ wanted to market itself in the European oil and energy market, it should market its quality advantage instead of its distribution advantage because SOCAR has a stronger distribution advantage than it does.

Nonetheless, there is no clear relationship between international trade and sustained competitive advantage, but because the international market provides the groundwork for market expansion, the comparative advantage theory provides the right model for the formulation and implementation of market innovation strategies. Therefore, the comparative advantage theory informs SOCAR’s market strategy in the European market. More importantly, this theory demonstrates how SOCAR can overcome the hurdles of operating in the European oil and energy market (through market strategy formulation). Indeed, the comparative advantage theory says companies, which take the initiative to re-invent their brands (say, by exposing their main ‘selling points’), stand a chance of ‘stealing’ business from companies, which do not bother to take such initiatives. By ‘stealing’ business from their customers, the main assumption of the comparative advantage theory is that a perfect economic equilibrium occurs (Shaw 2005, p. 206).

Coincidentally, re-inventing a company’s activities polish different facets of its operations, such as marketing and product/service innovations (thereby, boosting its chances of moving up the hierarchy of organisational competence). For example, by venturing into the European market, SOCAR will have to abide by international/global standards of operation, thereby improving the quality of its operations. Interestingly, capital always moves to companies that have the initiative of re-inventing themselves and the commitment to sustain their comparative advantages. Usually, this observation is true, irrespective of the existing socio-economic differences in a country (Goel 2009).

The comparative advantage theory acknowledges the barriers to capital inflows, but the theory also acknowledges that such barriers cannot reverse the trend towards economic superiority/dominance of ‘strong’ companies. A company’s resource heterogeneity and the ability to transfer resources should ordinarily amount to sustained economic advantage. However, because there are barriers to trade (like causal ambiguity, historical dependencies, and social complexities) this outcome is normally untenable. Investments in market strategies (for strong companies) create a pathway for the flow of organisational capital; however, more importantly, it provides an opportunity for organisations to sustain their comparative advantages (Goel 2009). This way, SOCAR stands to gain from exposing and sustaining its comparative advantages.

Ideally, after applying the principles of the comparative advantage theory (to the context of this study), SOCAR can easily succeed in the European oil and energy market if it carefully adopts a prudent and well-calculated marketing strategy (because this will be the only guarantee that the company can perform better than the existing competition) (Zoephel 2011). A liberal market environment would guarantee such an eventuality, and since the European oil and gas market is liberal, such an outcome is highly probable.

Summary

The decision to venture into a new market is becoming an ordinary phenomenon for most companies that have enough resources to do so. It is highly unlikely that this trend will change in future. SOCAR has realised this opportunity, and it has already started setting up new offices in the European market. However, based on the nature and number of players in the European oil and gas sector, SOCAR is not going to have an easy time trying to improve its visibility in the European market. First, competition is going to be a big hurdle for the Azerbaijan multinational, considering some of the world’s renowned oil companies control the European energy market. Therefore, it would require a well-formulated marketing plan to guarantee the efficacy of SOCAR’s market strategy in the European market. Another hurdle SOCAR is going to face emanates from the dwindling prospects of exploiting European oil because the European global output of oil and natural gas has been on a steady decline.

This situation is disadvantageous to SOCAR because it limits the possibility of offering specialised services in oil exploration and exploitation. Therefore, the only opportunities viable for the company constrain within the framework of oil distribution and the sale or promotion of its oil products. Even the execution of these possibilities may be a daunting task because there is a ‘green’ trend within the European oil and gas sector where consumers are encouraged to adopt ‘green’ and alternative energy sources. However, the comparative advantage theory (among other theories discussed in this literature review) shows that there are enough opportunities for SOCAR to expand successfully in the European oil and energy market. Subsequent sections of this paper demonstrate how SOCAR may bridge the gap between this theoretical and practical knowledge.

Methodology

This research methodology seeks to gather and compile different databases to have a deeper conceptual understanding of the research problem and to have a realistic and factual understanding of the marketing strategies that SOCAR may adopt in Europe. In addition, this research methodology aims to explain which marketing strategies are most beneficial for SOCAR, which business sectors SOCAR needs to concentrate on as it ventures into the European oil and gas market, and which resources SOCAR needs to use to achieve success in the European market. These questions also outline why company resources are crucial to SOCAR’S marketing strategy and how SOCAR can use its marketing strategies to circumnavigate the pitfalls of the European oil and gas market. These insights provide a deeper understanding of the research topic. They will also go a long way towards answering the research questions.

Research Design

Based on the nature of the research problem, this paper uses a qualitative research methodology. The selection of this methodology stems from the little knowledge about the scope and nature of the research topic (at the start of the research). Furthermore, the qualitative research design was preferred as the initial research methodology that pre-empted any future research. Therefore, the importance of adopting the qualitative research design is to have a holistic and conceptual understanding of the research questions. Furthermore, among the main motivations for adopting the qualitative research design is its ability to integrate information for case studies and its ability to accommodate research dynamics that unfolded during the research. Finally, the subjective nature of qualitative research was also a huge attraction for this study (Kelle 1995).

However, the use of qualitative research design is also subject to criticism because of its ambiguity in the application and the underdevelopment of its potential. One major disadvantage of the qualitative research design is its tendency to rely on small population samples. Having a small population sample usually reduces the probability of generalising the research findings. However, it is equally important to note that qualitative research designs are time-consuming, and it is difficult to undertake an effective research process using a large population sample. Therefore, the use of a small population sample in a qualitative research design is often unavoidable. This is a big limitation of this research design. Lastly, it is often difficult for qualitative research to ascertain the truthfulness of the information obtained or even to justify their responses by including responses from other groups. Comprehensively, these issues highlight the weaknesses of the qualitative research design.

Data Collection

Many researchers have studied the concept of international marketing, but few have focused on the intrigues of the oil market. More so, even fewer studies investigate the practicalities of implementing such marketing strategies in the European oil and gas industry. Based on this understanding, this study focused on introducing a new analysis of the successful marketing strategies that could be implemented by SOCAR (and similar foreign companies) to venture into the European oil and gas market. The data collection process sourced information from secondary and primary research data. The secondary research data mainly contained information from published sources like books, journals, and reliable websites. Since the reliability of secondary research information was questionable, this study also included primary research data by interviewing professionals and experts who were knowledgeable about the European oil and gas market, or the possible strategies that a foreign company could adopt while venturing into this market. Primary research provided a self-check mechanism for the study, where the primary research data counter-checked the secondary research information. Therefore, any disparities and inconsistencies from the two sources of data were easily detected (Valtonen 2006).

Validity of Data

The validity of the data collected mainly depended on the credibility of the secondary and primary data collected. As mentioned in earlier sections of this paper, books, journals, and online data constituted the main secondary research sources. The credibility of these information sources guaranteed their validity. For example, since books and journals contained published and peer-reviewed data, it was easy to uphold the credibility of the information obtained here. Scholars perceive published and peer-reviewed information to be reliable because the authors subject them to a rigorous credibility-review test, which assures the readers that the information published, is factual, and error-free. Furthermore, peer-reviewed sources allow for the diversity of information, thereby eliminating the possibility of including personal-bias or pre-conceived ideas into the research process (Rachels 1986, p. 56). Finally, the professionalism of the respondents guaranteed the credibility of the information obtained because all the respondents sampled were working professionals. Indeed, registered and reputable oil consultancy firms provided the respondents to complete the research questionnaires. Therefore, based on the experience and knowledge of these firms, the opinions of the experts were well informed.

Sample Population

The sample population comprised of ten experts and professionals who had sufficient knowledge about the European oil and energy market. Efforts to obtain credible research participants centred on interviewing employees at the managerial level because they were more versant with the strategic decision-making processes of oil companies and the market intrigues of the European oil and gas sector. To have an accurate assessment of the research questions, consulted members came from the managerial team, or their close confidants. There was no limitation to the position held at the managerial level because, at the beginning of the research process, there was strong anticipation of difficulties in accessing the chief group chairperson.

Therefore, any available member of the management team was an acceptable candidate for the interview. At the end of the study, interviews for eight managing directors occurred. The remaining two interviewees were a marketing manager and a senior strategic management officer. This interview body provided a diverse pool of knowledge about the research topic. The top-level managing directors provided a more comprehensive and broad analysis of the research questions because they had a broader understanding of the European oil market and the existing strategies adopted by energy companies in this market as well. The lower-management team provided an intermediary analysis of the research questions because they knew the practicalities of the energy market better than top management. These experts and professionals came from two oil consultancy firms (five respondents came from each firm).

Data Analysis

For purposes of data analysis, this paper used interpretive, coding, and member-check techniques. These data analysis tools have high reliability when evaluating secondary and primary research data. The interpretive data analysis technique emphasises the need to have a strong idiographic focus on the insights of a person or author. In other words, this technique tries to investigate how a respondent or author makes sense of a given issue. These experiences may concern a personal experience held by the respondent or the development of an important relationship by an author, respondent, or any information provider. In detail, the interpretive data technique structured the findings of the secondary research data. Since the secondary research sources contained numerous volumes of data, the interpretive technique eliminated irrelevant information from the final findings to provide a structured impression of the overall outcomes.

One criticism of the interpretive data analysis technique is its tendency to have a very close involvement of the information sources and the actual outcome of the study. Some pundits say this close involvement is often time-consuming (Kelle 1995). A less involved study would provide more opportunity for the researchers to undertake a more comprehensive study. Moreover, the close involvement of respondents in this analysis technique makes them less honest about their responses, especially when they have huge stakes in the research. Overall, this weakness lowers the integrity of the findings.

The coding technique complemented the work of the interpretive technique, but its use was clearer in the organisation of the research data. In detail, the coding technique worked by assigning codes to related data sources. Like the interpretive data technique, the coding technique also provided an interpretive eye to the research findings by segmenting the huge volumes of data into related segments and assigning relevant codes for easy analysis (Kelle 1995).

One criticism of the coding technique stems from its generalisation of research data into different groups. Therefore, this technique fails to appreciate the small differences that exist between different data groups. Therefore, it is easy to overlook small details differentiating the information obtained from different data sources. Another criticism of the coding technique stems from its data storage/grouping mechanism. One code holds a huge volume of information. The loss of this code could, therefore mean the loss of a lot of information.

Finally, the member check technique analysed the primary information obtained by evaluating the accuracy, credibility, and transferability of the information obtained (from the professionals in the oil and energy market). Ordinarily, the member-check technique establishes the variables between the source of the information and the eventual reporting of the same information. A high similarity rate shows that the findings of the study have high credibility and a low similarity rate shows that there are many discrepancies in the findings of the study (Valtonen 2006). Relating to the views sourced from the professionals, an expression of the feelings, attitudes, and experiences of the authors define credible research outcomes.

Ethics Statement

The research process adhered to relevant ethical principles. For example, the study upheld the anonymity of the respondents throughout the research process. However, for future reference, the names of the respondents were safely stored. In addition, the respondents felt reassured that any information gathered from the entire research was for academic purposes only. Therefore, they did not have any reason to doubt the purpose of the study or believe they were going to be penalised or deceived to participate in the research. Furthermore, none of the respondents felt coerced to participate in the research study. All the respondents participated in the research on their personal volition. Through the assurance that the research process would be undertaken ethically, the respondents felt safe to participate in the study.

Discussion

After evaluating previously highlighted dynamics of the European oil and energy market and factoring the dynamics of the industry explored by the experts sampled, this chapter reviews some of the most notable dynamics of SOCAR’s marketing strategy in the European market. Complementarily, to have a more comprehensive understanding of how to position SOCAR in the European oil and gas market, this chapter uses Kotler’s marketing framework (4Ps). The design of this framework explains product (service), place, price, and distribution as the four main components of a comprehensive marketing plan (Mehmet 1999). This framework organises the outcomes of the entire research process.

Product/Service

Considering the responses given by the sampled industry professionals and a review of the activities undertaken by SOCAR (pertaining to the dynamics of the European oil and gas market), the best bet for SOCAR to improve its visibility in the European oil and gas market is by marketing itself as an experienced oil distribution company. This marketing framework positions the company effectively with the current and future needs of the European oil and gas market (oil distribution). There is enough evidence gathered from the oil experts sampled to show that the primary concern for most European countries hinges on the availability of a safe and reliable oil transportation network (Osborn 2005). Previous research confirms that there is a lot of concern expressed by many European countries regarding the disruption of oil distribution systems by hostile countries.

Therefore, many European countries are looking to invest in new oil pipelines that are safe and reliable. This concern heralds a new opportunity for oil distribution companies to take advantage of this opportunity and fill the market void. SOCAR strategically can do so. Therefore, SOCAR can market itself as a viable and reliable partner in oil distribution because its other areas of specialisation like oil exploration and production are constrained by competition from other oil companies in Europe. Furthermore, the declining production of European oil constraints its contribution to the European oil and gas industry. For example, regarding oil exploration, this paper establishes that there are insufficient opportunities in Europe to undertake viable economic oil prospects. Therefore, many European countries are not looking for partners in oil exploration or exploitation. Instead, many countries are sourcing for reliable foreign oil distribution companies that provide a steady supply of oil to their countries.

Concerning oil production, SOCAR is constrained by geographic limitations of oil distribution. For example, it can only economically supply oil to European countries that are in close geographic proximity to Azerbaijan. It would be uneconomical to transport Azerbaijan oil to western European countries (like the UK, for example) because of the geographic distance and the sheer cost of constructing oil pipelines or shipping oil products across the continent. Therefore, the best alternative for SOCAR is to market itself as an oil distribution company, which can offer tremendous expertise in the construction of oil distribution infrastructure to link European markets with their nearer oil sources.

Place

SOCAR’s main problem is insufficient market visibility throughout the European market. A large cross-section of the literature studied in this paper also shows that many players dominate the European oil and gas market. This fact shows that competition is also another major hurdle that SOCAR has to overcome as it tries to improve its market visibility in Europe. However, for SOCAR to increase its geographic visibility across the continent, this paper proposes the adoption of a joint venture strategy with a European oil company. SOCAR can enjoy many advantages from the adoption of the joint venture strategy. However, practically, the joint venture strategy is beneficial to SOCAR because it helps it to collaborate with two or more oil companies in the European market to increase its geographic presence (Pongsiri 2004).

Such joint venture strategies are not new to SOCAR because the company has already adopted this strategy with Foster Wheeler in Azerbaijan to establish a new complex for oil and gas processing (Pongsiri 2004). This strategy has been largely successful, and it has created an excellent engineering conglomerate that dominates oil and gas projects in Azerbaijan. SOCAR may adopt the same strategy in Europe if it collaborates with other European oil companies to create a similar oil distribution conglomerate that will dominate most oil concessions in the continent and most importantly, increase the company’s visibility in the European oil and gas market. Going it alone is not a viable strategy for SOCAR because many players already dominate the market. Therefore, collaborating with the best market player is a more prudent decision to increase the company’s market visibility in Europe.

Price

Based on existing literature explaining the progressive trend of the European oil and gas market, many authors have established that the pricing formula used in the European oil and gas market is largely dependent on global oil prices (Amineh 2010). Based on this understanding, SOCAR’s pricing strategy is subject to global intrigues in the oil and gas market. However, since this paper focuses on oil distribution as SOCAR’s main service offing, the company’s pricing strategy will largely depend on operational costs such as material costs, labour costs, profit margins, and the likes to determine its pricing strategy in the European market. It is crucial for SOCAR to adopt a two-fold pricing policy aimed at increasing the company’s market presence in the first years of operations. Later (after the company has gained enough market visibility), it may adjust its price accordingly to reflect its new dominant status in the market. In detail, SOCAR needs to adopt a low-end pricing strategy in the first years of operations, and later, it can increase its price quote. Since competition is equally an important factor affecting SOCAR’s pricing strategy, the company needs to bid for tenders at a relatively lower price than its competitors do. This pricing strategy will give it an edge above its competitors and more importantly increase its market visibility in the region.

Promotion

SOCAR’S quest to increase its market visibility largely depends on its promotional campaign. Conversely, the effectiveness of the promotional campaign depends on its ability to reach and convince its target market that it is the best option to consult with when undertaking energy projects in Europe. Since the oil and gas industry has a few dominant players, SOCAR’s promotional strategy needs to base on person-to-person marketing. In detail, SOCAR needs to recruit effective sales and marketing personnel to negotiate and engage oil stakeholders (mostly governments) to secure business in the energy industry. The partnership strategy proposed in this study also complements this strategy because SOCAR will be able to participate in promotional campaigns undertaken by its partner as well. Finally, SOCAR may increase its corporate social responsibility campaigns (CSR) in Europe so that it receives more press as a responsible company in energy production and distribution (Amineh 2010). Currently, the main CSR project that may be beneficial to the company involves environmental conservation. Such projects complement the European quest to conserve the environment (alongside the ‘green’ energy campaign).

Summary, Recommendations and Conclusions

Summary

This paper demonstrates that many oil players (who have increased the industry’s barrier to entry) flood the European oil and gas market. This situation is similar to most oil markets around the world where a few oil companies dominate the market. In addition, this paper also demonstrates that there are limited prospects for SOCAR to position itself as a formidable force in the European oil and gas market because of the limited opportunities for growth in the sector. However, this paper shows that the best bet SOCAR can make to expand its market visibility in Europe is to position itself as an oil distribution company – in line with the intention to improve the European oil and gas distribution network. This conclusion stems from a preliminary analysis of a two-faced understanding of the European oil and gas market and the internal operational dynamics of SOCAR, which shows that the market needs better oil distribution infrastructure and a reliable partner to fulfil this need. Therefore, this paper has merged the best alternatives existing in the internal and external market spheres to establish an appropriate marketing plan for SOCAR. These alternatives also complement SOCAR’s key competencies in oil distribution.

Recommendation

This paper proposes a deeper understanding of the effect that alternative energy will have on SOCAR’s marketing strategy (based on the growth of the oil industry through the discovery of new oil prospects in other parts of the world, such as Africa). The emergence of the ‘green’ initiative damps the prospects of seeking the services of traditional oil companies to support energy initiatives in Europe. In fact, Europe is a signatory to environmental conservation agreements (like the Kyoto protocol) to reduce the world’s carbon emissions. Therefore, since SOCAR is a traditional oil company that specialises in the production and distribution of fossil fuel, European customers may shun it as they seek more environmentally friendly ways of meeting their energy demand. SOCAR is not the only oil company facing reduced market acceptance (because of the adoption of ‘green’ energy); many oil companies are similarly facing this hurdle.

Since the trend to adopt ‘green’ energy can only strengthen, SOCAR should rebrand itself as an ‘environmentally conscious’ company that works to reduce its carbon footprint as well. Therefore, even as SOCAR markets itself as the best oil distribution company in Europe, it should do so by proposing environmentally friendly alternatives to improve Europe’s oil infrastructure. Creating the perception, that SOCAR is ‘environmentally conscious’ is an important component of the company’s branding strategy because European partners would not want to be associated with a company that has a bad environmental record. Comprehensively, it would be interesting to know how major oil players like SOCAR position themselves (viz-a-viz the ‘green’ energy movement) because they have already marketed themselves as supporters of the ‘green’ revolution (yet, they profit from oil activities). Essentially, such companies should rebrand themselves as environmentally conscious entities to eliminate the perception that they are key contributors to environmental degradation.

Conclusion

Improving SOCAR’S market visibility in the European oil and gas market is an achievable goal. However, based on the market intrigues highlighted in this paper, this prospect largely depends on SOCAR’s ability to execute a perfectly calculated marketing strategy. This paper fragments SOCAR’s marketing strategy into four main components (product/service, place, price, and promotion). This paper proposes that SOCAR should market itself as an oil distribution company so that it can reap the benefits of an expanding oil distribution network in Europe. This marketing strategy should be SOCAR’s main marketing pillar. Concerning SOCAR’s pricing strategy, this paper proposes that the company needs to price its services slightly lower than its competitors do so that it can improve its market share during its first few years of operation. After this objective materialises, SOCAR may increase its prices accordingly to reflect its new market dominance in Europe. This paper also proposes that personal selling should be SOCAR’s main promotion strategy so that it can effectively communicate with its services to potential customers. Finally, this paper suggests that SOCAR should pursue a joint-venture strategy so that it can increase its market presence and avoid a protracted competition with the dominant oil players in the European oil and gas sector. Comprehensively, these strategies will increase SOCAR’S market visibility in the European oil and gas market.

Self-Reflection

In this paper, I sought to identify SOCAR’s marketing strategy in Europe after merging European market opportunities and SOCAR’s key competencies. This analysis created a compressive marketing plan based on Kotler’s four Ps of marketing (price, promotion, place, and product). This marketing strategy developed through the incorporation of international marketing theories that emphasised the need for SOCAR to manifest its key competence – oil distribution. Throughout the research process, I was satisfied with the comprehensive approach adopted to formulate SOCAR’s marketing plan and the overwhelming willingness of some of the respondents to answer the research problem. My biggest disappointment with the entire project stemmed from the little emphasis I accorded to the influence of the ‘green’ energy revolution on SOCAR’s marketing plan and the failure to investigate the differences in business practices between foreign and local European companies. These differences surfaced during the research. Overall, the research experience was fulfilling and informative.

Investigating the different types of marketing strategy, SOCAR could adopt in the European oil and gas market required an extensive understanding of the company performance, successes, and previous marketing strategies of the company. Investigating the structure and performance of the European oil and gas market also provided some useful insights to the research problem. By investigating the market structure and characteristics of the European oil and energy market, it was easy to establish the market opportunities that existed for foreign companies to exploit. In addition, understanding the key market characteristics of the European oil market and the history of SOCAR helped to identify the company’s key competencies to apply in the European energy market. Furthermore, through the understanding of the European market and SOCAR’s company structure, this paper employed a two-faced marketing approach for formulating SOCAR’s marketing strategy in Europe.

From the onset of the project, I had a lot of pessimism regarding the willingness of oil consultancy firms to participate in the research (without any form of persuasion). Moreover, I was more pessimistic about the probability of senior-level managers to share their insights regarding the research topic or the characteristics of the European oil and gas market. However, contrary to my expectations, many managers were available for interviews. Only two managers were unavailable to participate in the study, but they recommended that I should seek assistance from supporting managers. This redirection proved useful to expanding the overall scope of the interview because I was able to get the insights of a marketing manager who was able to provide a marketing perspective on the research topic (which was crucially important because this paper was market-centred). The sheer willingness of the participants to participate in the study surprised me.

Throughout the research process, I also learned a few insights regarding the European oil and gas market (that I did not know). For example, I was not aware of the decline in the European oil industry, which stemmed from the decline of oil reserves in most European oil-producing nations. Furthermore, it only came to my realisation that Europe stakes a claim to most global energy production and distribution processes because of the presence of dominant oil firms in the continent. Indeed, big oil firms like BP and Shell base their operations in Europe, and most of them have huge stakes in other global oil companies. Therefore, the influence of Europe on the global oil market is profound, and it is difficult for foreign oil companies to venture into their home markets. This realisation highlighted the difficulty that SOCAR would experience in the European oil market because it would play a secondary role in dominant oil companies in the region. This realisation informed the decision to propose a joint-venture strategy between SOCAR and another dominant oil company in Europe.

From the experiences learned by undertaking this research paper, I understood the importance of accommodating unforeseeable issues regarding the research topic. Indeed, while formulating a research plan, it is difficult to have a comprehensive conceptualisation of everything that happens in the research. In fact, there seems to be a big divide between the theoretical expectation of the paper and the practical expectations of the same process. Since it is difficult to know what to expect in the research process, it is crucial to account for unforeseen issues in the research process. Somewhat, the adoption of the qualitative research design helped to accommodate unforeseen research questions, but in my future studies, I will provide more opportunities to accommodate unforeseen dynamics of the research project.

After experiencing all the intrigues of this research project, I could have done several things differently. First, I wish I could have had a larger population sample to provide a more dynamic set of views regarding the research topic. Having a small representative sample reduces the ability to generalise the study’s finding. Furthermore, having a small representation of respondents reduces the credibility and validity of the findings because a larger population sample is more representative and practical about the prevailing market dynamics.

Having a more balanced approach for investigating SOCAR’s key competencies would also improve the credibility of the findings because all the respondents sampled were European. There was therefore little consideration about the views of SOCAR’s employees or even the views of Azerbaijan oil consulting companies. With more research resources, it would be easier to get more contributions from easily accessible experts like Azerbaijani employees. The limited literature regarding Azerbaijani business practices also limited the scope of market intrigues that could be included in the research. Most of the literature available focused on European business characteristics and successful marketing strategies in the western world. Nonetheless, there is a difference in the business practices adopted in Azerbaijan and Europe. Experts also emphasise the need to understand cultural differences in international business. This consideration should have been an important part of this study. Besides, the challenges and oversights I experienced in the research process, the overall experience of the research was informative and fruitful.

References

Amineh, M 2010, The Globalization of Energy: China and the European Union, BRILL, New York.

Auty, R 2006, Energy, Wealth And Governance In The Caucasus And Central Asia: Lessons Not Learned, Taylor & Francis, London.

Ceric, E 2012, Crude Oil, Processes and Products, Emir Ceric, London.

David, P 2010, International Logistics the Management of International Trade Operations, Cengage Learning, London.

Gammie, B 1997, ‘Employee assistance programmes in the UK oil industry: an examination of current operational practice’, Personnel Review, vol. 26 no.1, pp. 1-10.

Gemini Geek 2011, What are Various Theories of International Business? Web.

Goel, D 2009, Theory of Competitive Advantage, Web.

Harbo, F 2008, The European Gas and Oil Market: The Role of Norway, IFRI, Paris.

Heinberg, R 2005, ‘Powerdown: options and actions for a post-carbon world’, European Business Review, vol.17 no. 5, pp. 12-19.

Ibrahimov, R 2007, State Oil Company of Azerbaijan Republic: Transition from National to Transnational Company or Demand of Time?, Web.

International Business Publications 2008, Turkey Oil and Gas Exploration Laws and Regulation, Int’l Business Publications, London.

Ismailzade, F 2006, Russia’s Energy Interests in Azerbaijan: A Comparitive Study Of The 1990’s And The 2000’s, GMB Publishing Ltd, London.

Kelle, U 1995, Computer-Aided Qualitative Data Analysis: Theory, Methods and Practice, SAGE, London.

Key Note Limited 2007, European Oil & Gas Industry Market Assessment 2007. Web.

Lerman, Z 2010, Rural Transition in Azerbaijan, Lexington Books, London.

Maneschi, A 1998, Comparative Advantage in International Trade: A Historical Perspective Edward, Elgar Publishing, London.

Mehmet, O 1999, Westernizing the Third World: The Eurocentricity of Economic Development Theories, Routledge, London.

Nicholson, W 2011, Microeconomic Theory: Basic Principles and Extensions, Cengage Learning, London.

Osborn, S 2005, ‘Discrimination in the oil industry’, Equal Opportunities International, Vol. 24 no. 3/4, pp. 1-7.

Oxford Business Group 2009, The Report: Turkey 2009, Oxford Business Group, London.

Pongsiri, N 2004, ‘Partnerships in oil and gas production-sharing contracts’, International Journal of Public Sector Management, vol. 17 no. 5, pp. 2-19.

Rachels, J 1986, The End of Life: Euthanasia and Morality, Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK.

Shaw, C 2005, Building Great Customer Experiences, Palgrave Macmillan, London.

SOCAR 2012, The State Oil Company Of The Azerbaijan Republic. Web.

SOCAR Trading SA 2012, State Oil Company of Azerbaijan Republic. Web.

Taiyou Research 2011, Oil and Gas Industry in Europe. Web.