Introduction

In behavioral economics, economists study how rare or scarce resources are allocated and distributed among individuals and members of society. While standard economics assumes that the decision maker is rational, economists have observed that many individuals deviate from the rational model. Such deviations are called anomalies.

Examples of behavioral anomalies are engaging in charitable giving, participating in punishment of anti-social behavior, exercising little, etc. The study of behavioral economics brings in basic concepts from a variety of fields of studies such as psychology, sociology, and even a little bit of anthropology. Because of this, there is no unifying theory of behavioral economics.

One of the most well-known deviations from the rational decision maker is the sunk cost fallacy. In most well-documented introductory Business and Economics textbooks, the reader is warned against committing what is commonly known as sunk cost fallacy. Sunk cost case examples are plentiful, ranging from the everyday personal stories, to other more profound and general observations of human behavior. In clearer terms, a cost is considered sunk when it is unable to be recovered. Because it is unable to be recovered, traditional economic theory claim that sunk costs have no impact on future payoffs, and should therefore play no role in rational choice.

However, no matter how rational this may seem, people are always affected by sunk costs when making decisions. Once an individual has made some sort of investment, whether it be time, money, effort, or emotion, he/she has a tendency to invest even more in an attempt to keep their investment from being wasted. Typically, it seems that the larger the size of his/her investment, the more the individual desires to continue to invest, even though the returns of the investment may seem no longer sensible.

Let’s take a look at one of the most well-known examples of sunk cost and its effects on decision making studied by Hal R. Arkes and Catherine Blumer in 1985. In their study, they demonstrate the effect of sunk cost on decision making through many different experiments. One of the experiments was a questionnaire, and the experiment assumes that the decision maker has already spent $100 on a ski trip to Michigan, and $50 on a ski trip to Wisconsin, only to realize that neither is refundable, reschedulable, nor resalable.

Believing that the Wisconsin ski trip will be more enjoyable, the decision maker is asked to choose on going to the more expensive trip, or the cheaper trip. Arkes and Blumer’s study revealed that although the money has already been spent, most people would choose to go to the more expensive ski trip, even though the more economic trip would have been more enjoyable. In this case, Arkes and Blumer found that “the larger sunk cost of the Michigan trip is influencing many subjects’ choice” (Arkes and Blumer 1985).

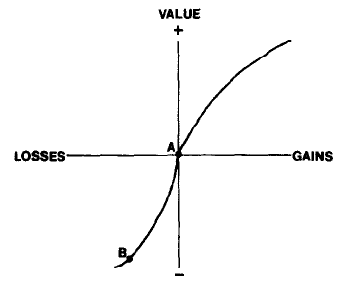

Arkes and Blumer explain sunk cost using prospect theory from Kahneman and Tversky’s research, with regards to a fixed reference point and loss aversion. These are two features of prospect theory that seem crucial to the analysis of the sunk cost effect (1985). The first is the value function of prospect theory, shown in Figure 1 below.

This function represents the “relation between objectively defined gains and losses… and the subjective value a person places on such gains and losses” (Arkes and Blumer 1985). Initially, an investor may be at point A, but after a significant loss has been acquired, the investor would be at point B. At this point, the investor would be more likely to risk more in order to obtain possible large gains.

According to Arkes and Blumer, this is consistent with studies by McGlothlin that unlikely victories at the race track are most popular at later times in the day when many of the crowd has suffered significant losses (1985). They are more risk prone than they were before any losses had actually occurred, because they’ve already lost much, another loss would not decrease their value by much. This would seem to show that sunk cost fallacy is highly influential in an individual’s decision.

There seems to be “two distinct psychological mechanisms that might create an irrational regard for sunk costs” (Friedman, Pommerenke, Lukose, Milam and Huberman 2004). The two are self-justification, which convinces people to continue investing in unprofitable activity for the sole purpose of delaying admission of their mistakes, and loss aversion, which might compel people to continue investment if there is a slight hope that the overall investment might be positive.

Baliga and Ely (2011) offer a new theory about the reason sunk cost fallacies exist in their study. They theorize that perhaps due to the cognitive limitations of human beings, individuals often experience sunk cost fallacies as a “substitute for limited memory” (2011). They claim that “as new information arrives, a decision-maker or investor may not remember his initial forecast of the project’s value” (2011). Participants were asked to decide on completing a particular project without the initial information of cost of initiation.

In their study, the experiment showed that students were more likely to complete investments the second round if the sunk cost of completion was lower. Through their study, Baliga and Ely found that memory constraints are “potentially an important source of a variety of behavioral regularities… [and] have shown how sunk cost arises naturally as a strategy for coping with limited memory” (2011).

In recent years, there are also research papers and studies that show that sunk cost fallacy may not be a surrender to irrational decision making. In McAfee and Mialon’s research, analysis of informational content, reputational concerns, and financial and time constraints are completed to show that perhaps reacting to past decisions is often rational.

The first of the three concerns, informational content, shows rationality because the higher the sunk cost (initial investment), the more information obtained, indicating that they are closer to success and completion of any project than not; reputational concerns are also important because impacting one’s reputation may affect future cost; and financial and time constraints are also important because a firm or organization may not have the capabilities of starting a new project with limited time or finances. As stated by McAfee and Mialon, “there is no clear evidence that people react to sunk costs in such situations and some evidence that they do not” (2010).

All in all, the effect of the sunk cost fallacy can be summarized based on the approach of McRaney (2011), who maintains that sunk cost fallacy and loss aversion often come together. The correlation between the two phenomena and the effect they produce on the behaviors of the individuals is simple – human beings are designed to avoid feeling suffering and pain; the loss of something (even if it is not an actual but perceived loss) is associated with pain.

As a result, under the impression that they are about to experience pain, the individuals do everything to avoid it. Using the example of investment in mobile games, the phenomenon of sunk cost fallacy can be explained as an individual’s reaction to the investment made in the past (it could have multiple aspects such as money, effort, or time spent by an individual playing that game). As a result, the correlation goes the following way: the larger the investment – the more difficult it is for a gamer to move on from it. Viewed in that way, the example of a ski trip cost used by Arkes and Blumer (1985) is perfectly applicable as an illustration of the motivation behind the sunk cost fallacy.

Motivational Game Design Patterns of ‘Ville Games

In an effort to further explore sunk cost fallacy and how it affects how certain companies take advantage of this concept in the business world, we turn to Social Networking Games (SNG) and their employment of sunk cost fallacy and loss aversion to maintain high user registration. This paper explores SNG structure and design, and analyzes how sunk cost fallacy, if it exists in this case, is applied towards game design in an effort to effectively engage their audiences.

In July of 2007, Zynga, a social network gaming company, was set up by CEO Mark Pincus. Since its creation, the company has over 246 million players, primarily through their “Ville series”, e.g. Farmville. One of the reasons this is such a shock to most game experts in the gaming industry is that these types of games, SNGs, defy the typical definition of a “good” game. A “good” game is defined by a series of interesting choice, constant learning, and positive stress (Lewis et al. 2012). But experts question whether SNGs really do any of these things. Most SNGs, like Farmville, are simple, easy to understand, contain very little challenge, and rarely induce any stress to the player.

Lewis, Wardrip-Fruim, and Whitehead compiled a study titled “Motivational Game Design Patterns of ‘Ville Games” in 2012. They studied various patterns that developed in SNGs that appeared to motivate players to return to the game even though they did not possess any of the typical “good” game characteristics. In all of the patterns that appear, withering is the most fascinating because of the emotional reaction it causes in a player. Withering, as described by the study, is powerful because this is one of the only characteristics that causes loss in the game. Punishment for not returning to a game has progressed throughout the years, as shown by Figure 2 here (Lewis et al 2012).

Figure 2: The cost and losses/gains from withered crops.

This theory can be applied in that the power given to withering crops is due to sunk cost fallacy. Crops are considered sunk costs. Once planted, it cannot be recovered. It can only be recovered through a timed return, and if the player does not return, the crops are lost and can even be punished by the game by having coins or money deducted. Players are therefore motivated to return to the game, whether or not they want to. Watching a movie, or doing something else that would provide more pleasure would be the more rational choice, but because of the game and the withering design, players are compelled to continue playing the game, to harvest their crops before the crops begin to wither.

Tobias Stockinger also further explored leveraging behavioral economics in mobile application design. In his group’s study, they concluded that applying behavioral economics can improve and increase user experience, causing a higher user rating. The Stockinger study further explores gamifications and how adding certain challenges, badges, and achievement acknowledgments can boost intrinsic motivation.

The study also discusses sunk cost and loss aversion as a gamification factor. Loss aversion, as described in this study is the “discrepancy between perceived intensity in gain or loss of things people own” (Stockinger et al.). In simpler terms, what this means is that people tend to have a higher emotional impact when losing things compared to gaining things. In games and mobile applications, this applies when people receive badges, trophies, and achievements as a result of invested time and effort. Once an individual owns a trophy, they are more likely to care about their progress in the game, thinking that until they have acquired all of the badges and trophies, prior time and effort put into the game would be wasted if they did not finish the game.

The approach exercised by McAfee and Mialon (2010) specifies that sunk cost fallacy is a rational reaction based on a logical choice of an individual, and not merely an instinct that is launched to avoid pain. However, regardless of how logical the choice of the individuals to keep playing and investing in a game is – it can be controlled by the game makers. Apart from the FarmVille example, there is another interesting demonstration in a best-seller called SimCity, a city-building mobile game. The game functions based on a mechanism that is designed to trigger the initial investment in order to launch the sunk cost fallacy chain reaction.

Basically, the game has an initial stage that is easy and addictive. This stage is followed by the next stage that causes a player’s frustration by generating multiple challenges at the same time. The easiest way to resolve the frustration is to invest a relatively insignificant sum of money and buy buildings and address the problems in the city. The first investments pave the gamer’s way towards more in-game purchases, which in turn lead to the growing cost of the playing process in terms of time, effort, and money. Finally, the gamer becomes attached to the game. This player involvement mechanism differs from one game to another, but the ultimate objective is the same – the encouragement of the client to make purchases and create an emotional attachment to the game.

Implications – Cow Clicker

Since the growth of mobile phone technology, mobile phone game applications have also grown significantly. Many new technology companies are beginning to focus more and more on mobile application development. It seems as though a technology company is not really legitimate until they have developed a mobile phone application that is user friendly and available on all mobile phone platforms (mainly iOS, android, and windows).

In this section, we hope to answer the question, why mobile phone games, particularly ones that lack the typical “good” game requirements continue to attract and acquire large numbers of users. We will do this by discussing a game, Cow Clicker, a parody of the ‘Ville games and its success. Because of the simplicity of Cow Clicker, behavioral economics can further be analyzed and easily distinguishable.

Cow Clicker was created by Ian Bogost, which gained more than 50 thousand players. Its game objective, is to click your own cow more than anyone else. However, throughout the game’s history, Bogost attempted to intentionally sabotage his game through a variety of methods, such as switching the default cow to another direction, or even charging $20 for the game. When neither of the methods worked, Bogost removed all of the cows, finally leading to complaints that the game without cows was not a very fun game.

Through this study, we were able to identify specific game design patterns that seem to encourage and motivate a group of people to return to a game that “is at best tedious, and at worst abusive” (Lewis et al 2012). Bogost himself even wrote a blog about the creation of this game, meant to be a parody of the social networking games that made Zynga a multi-million dollar valued company within such a short time frame.

He claims that Cow Clicker is a game created to make fun of the ‘Ville games that gained so much popularity, and even continues to argue four points against social networking games. Bogost argues that SNGs, such as ‘Ville games, and his own Cow Clicker game defy the typical game stereotype. He claims that compulsion, optionalism, and destroyed time are reasons that make the mobile game unattractive and devalues the game industry. The first reason, compulsion, refers to the idea that SNG companies are exploiting human psychology to make money. This is where sunk cost fallacy and loss aversion really come into play.

Cow Clicker utilizes sunk cost fallacy to attract and motivate game players to return to the game. At its peak, there were 48,542 clickers, with approximately 2.2 million clicks. It combines this aspect with the endowment effect as well as an altruistic attitude in the game. This pattern exists in Cow Clicker when a player can collect different cows, place it in his/her neighbor’s pasture, where every click on a player’s cow results in a click on his or her own pasture.

Players begin to form strong bonds as they are compelled to work together, cooperating with each other to help each other’s pastures grow and rise in rankings and accomplishments. After seeing the neighbor’s accomplishments and achievements, players are often motivated to continue playing so that they can surpass their friends. Not doing so, and quitting in the middle of the game is not fathomable – players feel like they’ve lost the game, and wasted so much time doing so if they are unable to surpass at least some of their neighbors and friends.

Such data seems to be consistent with the theory of sunk cost fallacy. With such a basic game design framework, where Bogost’s (the creator of Cow Clicker) main goal was to satire the simplicity and lack of design in a game, Cow Clicker should not have been a popular game. But the fact that it became such a popular game so quickly seems to point out that behavioral economic theories are more important than ever in attracting users.

Time inconsistency – When discussing behavioral economics, the differentselfs of a decision maker can have different preferences over current and future choices. Time inconsistency, is therefore, related to this particular concept.

Time inconsistency is actually quite standard in human preferences in decision making. For example, if we had to choose between getting one day off tomorrow or getting one and a half days off one month from now, most people would choose to get one day off tomorrow. However, if we were to make that decision ten years ago, the decision would be different. This shows that people’s preferences change throughout different points in time, and shows that humans have a preference for immediate pleasure.

Mobile phone games can take up a lot of time, and often times, at the most inconvenient of times. However, people often display a consistent bias that they will always have more time in the future than they have today. That is why, for many mobile phone game players, investing time in games today is often worthwhile, because they often feel that in the future, they will have more time to play the game, and therefore, feel less inclined to stop playing the game today.

When intertwined with sunk cost fallacy, most mobile phone game players find themselves incapable of keeping themselves off of the game. Generally, the utility an individual gains in playing mobile phone games generally does not change between now and later. Even with time discounted utility, a player who plays a game now, would not gain much in utility in the far future. When meshed with sunk cost fallacy, the player would find it rather difficult to refrain from investing time into that particular game.

There may be times when playing this game would provide the player with some substantial tangible utility and value. It is these times, that the player has to make a decision. He must decide whether or not it is worth playing now, and whether or not he will have time to continue with the game. Because discontinuing the game in the future would be a waste of time (sunk cost fallacy). He would much rather continue a game, than start a new one. Embedded in this decision is the whether or not he will have enough time in the future to play this game, and whether or not its worth it. Because of time inconsistency, and the bias that he will always have more time in the future, the player often misjudges whether or not he will have enough time to play the game.

In general, the sunk cost fallacy is driven by human emotions creating an illusion of a loss associated with an individual’s decision to stop a certain behavioral pattern. In that way, initially, the costs invested in a game are recognized as the effort and the results (or the purchases) as the achievements. Consequently, it becomes more difficult for one to neglect all this “effort” and stop playing the game. As a result, the continuation of the pattern is justified as the pursuit of satisfaction, pleasure, and entertainment, while, in reality, it is just the avoidance of negative emotions. This behavior could be compared to a drug addiction, in which the dependent individual continues to purchase and abuse substances, not to feel good but to stop feeling bad.

Conclusion

In conclusion, SNGs are games that take advantage of the human psychology. Its popularity provides evidence that sunk cost fallacy and loss aversion stands true. SNGs are games that provide little value or entertainment for its players. Other than a means to absorb and destroy the value of time while users are away from the game, SNGs hold little value as a “good” game.

It is clear that sunk cost fallacy is heavily exploited as a means to motivate and encourage gamers to return to the game, even if that time on the game could be better spent elsewhere and doing more productive things. Although some research has shown that perhaps sunk cost fallacies do not really matter when considering investment projects, they definitely do apply when companies such as Zynga think about how to increase user ratings and number of users.

Reference

Arkes, Hal R, and Catherine Blumer. “The Psychology of Sunk Cost.” Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes: 124-40. Print.

Baliga, Sandeep, and Jeffrey C Ely. “Mnemonomics: The Sunk Cost Fallacy as a Memory Kludge.” American Economic Journal: Microeconomics: 35-67. Print.

Garland, Howard, and Stephanie Newport. “Effects of Absolute and Relative Sunk Costs on the Decision to Persist with a Course of Action.” Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes: 55-69. Print.

Lewis, Chris, Noah Wardrip-Fruin, and Jim Whitehead. “Motivational Game Design Patterns of ‘ville Games.” Proceedings of the International Conference on the Foundations of Digital Games – FDG ’12. Print.

Mcafee, R. Preston, Hugo M. Mialon, and Sue H. Mialon. “Do Sunk Costs Matter?” Economic Inquiry: 323-36. Print.

McRaney, David. “You Are Not So Smart.” New York, New York: Avery, 2011. Print.

Stockinger, Tobias, Marion Koelle, Patrick Lindemann, Matthias Kranz, Stefan Diewald, Andreas Möller, and Luis Roalter. “Towards Leveraging Behavioral Economics in Mobile Application Design.” Gamification in Education and Business (2014): 105-31. Print.